Musculoskeletal Intervention

General Principles

Introduction

Setup

In most cases, a complex setup is not required and most injections can be carried out as an adjunct to the basic ultrasound examination. Syringes and needles that are found in most departments and wards are sufficient. Simple sterilization measures have kept the incidence of infection very low. The routine use of a sterile probe cover is a matter of personal preference or local policy.

For many injections, a standard footprint probe can be used. If available, a smaller footprint probe, sometimes referred to as a ‘hockey stick’ probe, can be used to bring the puncture point closer to the target (Fig. 29.1). This is particularly helpful for very superficial structures such as interphalangeal joints.

Treatment Rationale

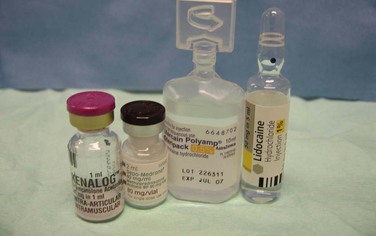

Injection therapy in inflammatory lesions is aimed at reducing the inflammatory response and pain. The commonest combination of injection therapy used is a mixture of corticosteroid and local anaesthetic (Fig. 29.2). The purpose of the local anaesthetic is to make the injection more comfortable and to assess the diagnostic response. Resolution of symptoms, albeit temporarily, confirms that the area injected is the pain generator provided the injection has been contained. There is no specific cellular inflammatory response in most overuse injuries, although many other chemical components of the ‘inflammatory’ cascade are present. Mucoid degeneration possibly augmented by a mechanical predisposition leads to repetitive injury and maladaptive repair. Injection therapy in this group is aimed at inducing more organized repair and relieving pain. Rehabilitation is the most important component in managing overuse injuries. This includes physical therapy, as well as analysis and adjustment of technique and equipment if faulty. For patients who have undergone an unsuccessful rehabilitation programme, interventional options include techniques involving controlled breakdown and tissue repair with or without augmentation by growth factor stimulation and techniques to reduce pathological neovascularization. A variety of methods of controlled reinjury have been advocated and these will be discussed below. Although corticosteroids can sometimes be successful in this group of patients, the mechanism of action is less well understood. Their mechanism of action and rationale for use are better understood in the truly inflammatory conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis or tenosynovitis.

Corticosteroids and Their Side Effects

Steroid Flare

One of the most common complications occurring following steroid injection is steroid flare. This is an inflammatory type reaction that comes on relatively quickly after the injection and may last 2 to 3 days.

The features of steroid flare are similar to infection; however, the relatively rapid onset occurring within hours usually differentiates these two conditions.

Steroid flare tends to occur in smaller joints rather than larger ones, and it has been suggested that the long-term response to injection is improved if steroid flare occurs. There is no particular method of preventing this side effect, although the prophylactic use of ice and analgesia may help to offset its effects.

Local Anaesthetic Preparations

Duration of Action

The diagnostic component of a local anaesthetic is less important in patients undergoing repeated injections following previous successful therapy, although it is still helpful to include some local anaesthetic to manage steroid flare.

General Principles of Ultrasound-Guided Injection

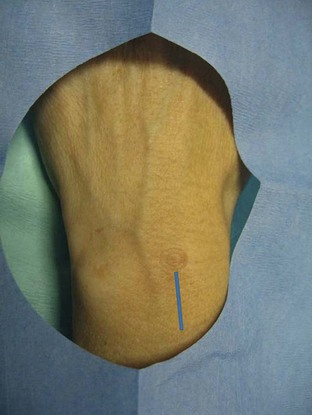

The patient should be in as comfortable a position as possible, preferably one where they do not have to observe the procedure. It is also important that the operator is comfortable and machine and couch heights should be adjusted as appropriate. It is probably better to have the side being injected closest to the operator so as not to have to stretch over the patient, though of course this cannot be avoided if both sides are being treated simultaneously. To begin, a preliminary examination is carried out and a mark is placed on the skin when the best puncture point and approach to the lesion is found. It is sometimes helpful to use the blunt end of a needle sheath to make the mark, as marking with a pen can be difficult in the presence of ultrasound gel. Alternatively two marks can be made at right angles to each other away from the injection point out of any skin gel. This is more appropriate for injection of larger structures. In addition, it is sometimes helpful to draw a line next to the mark, giving the initial direction of approach for the needle (Fig. 29.3).

Figure 29.3 A small circular mark has been made on the patient’s skin by gentle compression with the open end of a plastic needle cover. This can be made through local anaesthetic gel where it is difficult to use skin markers. If necessary a line can also be drawn indicating the initial needle direction.

Thought should be given to the choice of puncture point and needle track. In addition to the obvious desire to reach the target without transgressing important structures, particularly nerves, there is also an advantage in choosing a course that keeps the needle as parallel as possible to the ultrasound probe.

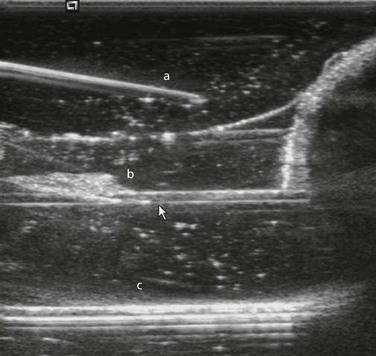

Visualization of the needle is best under these circumstances (Fig. 29.4). If a parallel approach is not possible, the closest alternative should be chosen. Beam steering or an asymmetrical gel layer can be employed to optimize the ‘probe to needle angle’ relationship.

Figure 29.4 Three needles have been inserted into gel. Needle a is inserted at a slight angle compared with needle b (arrow). The reflectivity of the latter is clearer. The discrepancy increases as depth increases. Needle c is specially formulated with a coating to increase ultrasound reflectivity. Although the needle is considerably more reflective, the additional expense in the majority of cases is not necessary.

Lidocaine is slightly acidic and may cause a stinging sensation that can be reduced by the addition of a small amount of sodium bicarbonate. If the target is very superficial, with experience, local anaesthetic is not required and can add to the discomfort of the procedure. If local anaesthetic is to be used, it is preferable to sterilize the skin and inject local anaesthetic before drawing up the other injection agents or preparing a sterile probe. This gives some time for the local anaesthetic to work before proceeding with the injection. A single puncture is recommended with local anaesthetic infiltrated using the same needle that will be used for the actual injection. Exceptions are where a large needle is to be used, such as for ganglion aspiration or in needle-phobic patients. In these cases the skin is anaesthetized with the smallest available needle.

Needle Techniques

‘In View’ Method

To relocate a ‘lost’ needle tip, the probe is moved away from the target towards where the needle tip is felt to be. Once the needle tip is located, the direction the probe had to be moved to find it is noted. The probe is returned to the target, the needle is retracted slightly and then moved in the opposite direction to bring it back into view. There is a tendency for needles to deflect away from the direction of the bevel, therefore for deep injections it is helpful to counter this tendency by rotating the needle.

Soft Tissue Biopsy

Important Principles

A detailed discussion on the diagnosis of soft tissue masses will be found in Chapter 31. The principal role of the ultrasound of masses is to confirm the presence of a significant mass, to distinguish fluid from solid lesions, to identify tissue and compartment planes and to guide biopsy. Biopsy of musculoskeletal soft tissue masses follows similar principles to the biopsy of other organs; however, there are several aspects that are important when sarcoma is suspected.

It is mandatory to discuss the biopsy approach with the surgeon who will be carrying out the definitive surgery. This is to ensure that the track can be excised through the surgical approach to reduce the incidence of track recurrence and, equally importantly, to ensure the biopsy does not worsen the prognosis for the patient by spreading the tumour to another compartment. Some authors advocate the use of a soft tissue dye to help the surgeon identify the biopsy track.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree