Introduction

In the emergency department setting, the use of head and neck ultrasound has become a valuable tool to expedite the diagnosis of familiar diseases and facilitate common procedures. For head and neck pathology, ultrasound is often favored over computed tomography (CT) because it is readily available at the bedside and does not expose the patient to ionizing radiation. In this chapter we will describe the ultrasound characteristics of common head and neck pathology and outline procedures where ultrasound can facilitate emergent procedures.

Anatomy of the Head and Neck

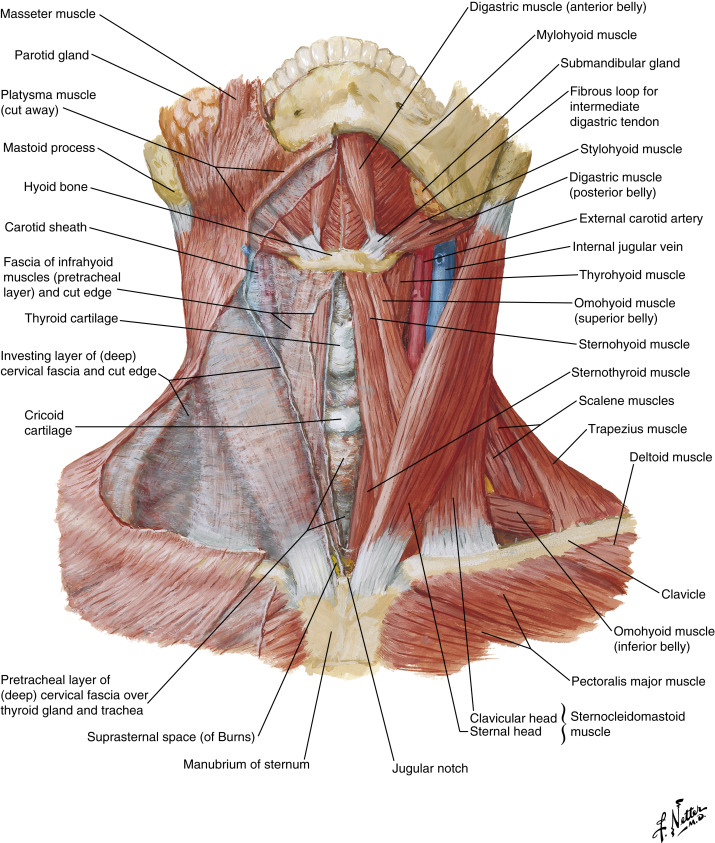

The neck is historically broken down into two triangles divided by the sternocleidomastoid muscle (SCM). The anterior triangle, which is bordered by the anterior aspect of the SCM, midline of the neck, and inferior mandible, can be further subdivided into the suprahyoid and infrahyoid compartments ( Fig. 4.1 ). The suprahyoid structures include the submandibular glands, the anterior and posterior bellies of the digastric muscle, the mylohyoid, and the stylohyoid muscles. The infrahyoid compartment contains the larynx, trachea, and esophagus, as well as the thyroid and parathyroid glands. Important muscles of the infrahyoid compartment include the sternohyoid, sternothyroid, thyrohyoid, and omohyoid muscles. The posterior triangle is bordered by the SCM anteriorly, the trapezius muscle posteriorly, and the clavicle inferiorly (see Fig. 4.1 ). In the posterior triangle sits the spinal accessory nerve, brachial plexus, and phrenic nerve. The common carotid artery, internal jugular vein, and vagus nerve sit deep in the SCM and are therefore located on the transition between the anterior and posterior triangles.

Imaging and Technique

Imaging of the neck is performed using a linear transducer with a frequency of 5 to 15 MHz. The choice of frequency will depend on the depth of the pathology, with lower-frequency probes providing better resolution of deep structures. Proper patient positioning is helpful for visualization of anatomic structures, particularly in the obese patient. The patient can be placed in the supine position and a shoulder roll inserted behind the scapulae to aid with extension of the neck. As with all ultrasound imaging techniques, a focused, systematic approach increases the efficiency of the study. Whenever possible, scan the neck in more than one plane to confirm findings.

In the anterior triangle start in the submental region and evaluate the submandibular glands and submental lymph nodes. Move inferiorly in a cranial-to-caudal fashion, noting the trachea as a midline structure with a hyperechoic air–mucosa interface and reverberation artifact. The thyroid gland is located in the midline of the infrahyoid compartment of the anterior triangle. The isthmus of the thyroid will overlie the trachea and connect the right and left lobes ( Fig. 4.2 ). The thyroid will be bound laterally by the common carotid artery and internal jugular vein. The appearance of the thyroid gland is characterized by two homogenous, well-circumscribed lobes connected by a thin isthmus that drapes over the trachea.

When examining the posterior triangle, it helps to have the patient rotate the chin contralateral to the side of examination. Examine the lateral neck in a craniocaudal fashion. The SCM is a bulky, hypoechoic structure overlying the internal jugular vein and common carotid artery. The jugular vein is usually superficial and lateral to the common carotid artery.

Pathology

Abnormalities of the Anterior Triangle of the Neck and Face

Thyroid Pathology.

Thyroid nodules are a common finding on neck ultrasound, occurring in up to 70% of women and 40% of men. A thyroid nodule is seen as a well-circumscribed, hypoechoic, isoechoic, or hyperechoic structure within the thyroid parenchyma. Large thyroid nodules may displace adjacent structures such as the trachea and internal jugular vein ( Fig. 4.3 ). Although the majority of nodules are solid, thyroid cysts are also common. Thyroid cysts appear as anechoic structures without internal vascular flow and with posterior enhancement of the deep margin ( Fig. 4.4 ). Approximately 90% of thyroid nodules are benign; therefore the National Comprehensive Cancer Network and the American Thyroid Association have created guidelines for nodules requiring further workup. Concerning features of malignancy include hypoechoic echotexture (when compared with surrounding thyroid parenchyma); microcalcifications, which appear as small, hyperechoic foci; infiltrative margins and irregular borders; and taller-than-wide orientation in the transverse plane. The decision to perform a fine-needle aspiration for malignancy is done in a nonemergency setting.

Goiters, or diffuse thyroid enlargement, are fairly common and can present as a large, mobile neck mass. Substernal goiters can extend deep into the mediastinum. Graves’ disease is an autoimmune disorder of the thyroid where the gland can become large and hypervascular ( Fig. 4.5 ). Patients often present with signs and symptoms of hyperthyroidism, including anxiety, palpitations, weight loss, and tremor . The ultrasound appearance of goiters will often show a large, heterogeneous thyroid, with or without numerous nodules. Tracheal deviation may be noted, as the tracheal air column can be seen off-center.

Anaplastic thyroid cancer is an uncommon entity that is usually seen in older patients. Unlike goiters, anaplastic cancer is usually rapidly growing and firm and fixed on physical examination. Ultrasound may demonstrate a large, poorly circumscribed neck mass with involvement of the trachea, strap muscles, or lateral neck vessels ( Fig. 4.6 ). The diagnosis of anaplastic thyroid cancer can usually be made on fine-needle aspiration.

Thyroglossal Duct Cyst.

Another example of pathology encountered in the anterior triangle is the thyroglossal duct cyst. Although thyroglossal duct cysts can occur at any age, most are detected before age of 20 years. They occur in the midline of the neck, from the base of the tongue to the anatomic position of the thyroid. Eighty percent are found adjacent to the hyoid bone. On physical examination a thyroglossal duct cyst appears as a soft, mobile mass that moves superiorly with swallowing or tongue protrusion.

On ultrasound, a thyroglossal duct cyst appears as a well-circumscribed, anechoic structure with posterior enhancement ( Fig. 4.7 ). Some have a pseudosolid appearance resembling normal thyroid tissue secondary to a proteinaceous component. The wall may appear thickened (3–5 mm) with rim enhancement if the cyst is currently or was previously infected. The presence of a central solid component to the cyst should raise concern for malignancy. Regardless of ultrasound characteristics, patients with thyroglossal duct cysts should be referred to a head and neck surgeon.

Conditions of the Salivary Glands.

There are three pairs of major salivary glands: the parotid, the submandibular, and the sublingual glands. The parotid gland is located in the retromandibular fossa, and its size is proportional to body weight. The submandibular gland is located medial to the mandible and is surrounded by the anterior belly of the digastric, the mylohyoid muscle, and the facial vessels. The sublingual gland is located in the floor of the mouth, medial to the mandible and lateral to the geniohyoid muscle.

Common conditions of the salivary glands presenting urgently include sialolithiasis, sialadenitis, and salivary tumors (benign and malignant). Sialolithiasis (stones within the salivary glands or ducts) and sialadenitis (inflammation of the gland) usually present with symptoms of pain and swelling that may be exacerbated by eating. Sialadenitis is due to an obstructive process. The most common etiology of obstruction is sialolithiasis, which leads to salivary stasis and ultimately infection. Kinks and strictures within the ductal system can also lead to infection and are usually caused by previous infection, trauma, or instrumentation resulting in inflammation or scarring of the duct. Viral disease, such as the mumps, can also lead to sialadenitis and is more common in unvaccinated children. Sialadenitis may be acute or chronic. The acute infection may result in an abscess and associated swelling of the gland. The peak incidence of acute sialadenitis is between 30 and 60 years and is more common in men. Chronic infections usually result from recurrent indolent inflammation in the setting of sialolithiasis. Over time, remodeling of the parenchyma takes place, and healthy gland tissue can be replaced by fibrosis.

Given the superficial location of the salivary glands, high-resolution ultrasound is the ideal imaging modality for evaluation. This is best performed with a high-frequency, linear array transducer. The first principle of evaluating a salivary pathology is to evaluate the glands in pairs. Comparison between the gland in question and its contralateral counterpart can confirm the presence of abnormal pathology. On ultrasound, salivary stones will have the characteristic appearance of a hyperechoic structure with posterior shadowing ( Fig. 4.8 ). Stones >2 mm in size can be detected by ultrasound. Acute sialadenitis appears as an enlarged, hypoechoic gland with increased vascularity.

Salivary gland tumors comprise a diverse spectrum of neoplasms with a broad range of outcomes. The majority of salivary gland tumors occur in the parotid gland. The risk of malignancy depends on the location of the tumor, with 75% of parotid tumors being benign and 40% of submandibular gland tumors and 80% of sublingual gland tumors being malignant. The most common benign tumor is the pleomorphic adenoma, usually located in the parotid gland. These tumors appear as well-circumscribed, homogenous, hypoechoic lesions with lobulated margins and moderate vascularity ( Fig. 4.9 ). Malignant salivary gland tumors include mucoepidermoid carcinoma, adenoid cystic carcinoma, undifferentiated carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, lymphoma, and squamous cell carcinoma. Ultrasound features concerning for malignancy include irregular borders, hypervascularity, heterogeneity, and necrosis. If there is suspicion for malignancy, follow-up cross-sectional imaging and biopsy are necessary in a nonemergent setting.