Pediatric bowel obstructions are one of the most common surgical emergencies in children, and imaging plays a vital role in the evaluation and diagnosis. An evidence-based and practical imaging approach to diagnosing and localizing pediatric bowel obstructions is essential for optimal pediatric patient care. This article discusses an up-to-date practical diagnostic imaging algorithm for pediatric bowel obstructions and presents the imaging spectrum of pediatric bowel obstructions and their underlying causes.

Key points

- •

The age of the patient and suspected location of an obstruction can help determine which imaging modality to use when imaging bowel obstructions in the pediatric population.

- •

Plain radiography is a first-line imaging modality to evaluate for signs and location of bowel obstruction.

- •

In neonates, fluoroscopic upper gastrointestinal series are helpful in evaluating upper intestinal obstruction, whereas a fluoroscopic enema may determine the cause and location of a lower intestinal obstruction.

- •

Ultrasound is an excellent noninvasive imaging modality in cases of pediatric bowel obstruction that are caused by acute appendicitis, ileocolic intussusception, and abdominal or inguinal hernias.

- •

Computed tomography often is used as a second-line modality to better localize an obstruction or characterize its cause.

Introduction

Pediatric bowel obstructions are one of the most common surgical emergencies in children, and imaging plays a vital role in the evaluation and diagnosis ( Tables 1 and 2 ). The main purposes of this article are to (1) discuss up-to-date evidence-based imaging algorithms; (2) describe a practical approach to pediatric bowel obstructions using imaging; (3) present the imaging spectrum of pediatric bowel obstructions and discuss their underlying causes; and (4) link imaging findings to management recommendations for practicing radiologists and physicians.

| High Intestinal Obstructions | Low Intestinal Obstructions |

|---|---|

| Esophageal atresia | Ileal atresia |

| Duodenal atresia | Meconium ileus |

| Duodenal web | Functional immaturity of the left colon |

| Duodenal stenosis/annular pancreas | Hirschsprung disease |

| Malrotation with midgut volvulus | Colonic atresia |

| Jejunal atresia/stenosis | Megacystis microcolon intestinal hypoperistalsis |

| Anal atresia/anorectal malformations |

| Congenital | Infectious/Inflammatory | Iatrogenic | Other |

|---|---|---|---|

| Malrotation w/midgut volvulus | Appendicitis | Adhesions | Ingested foreign body |

| Meckel’s diverticulum | Ileocolic intussusception | Acquired hernia | Distal intestinal obstruction syndrome |

| Congenital inguinal hernia | Inflammatory bowel disease |

Evidence-based imaging algorithm

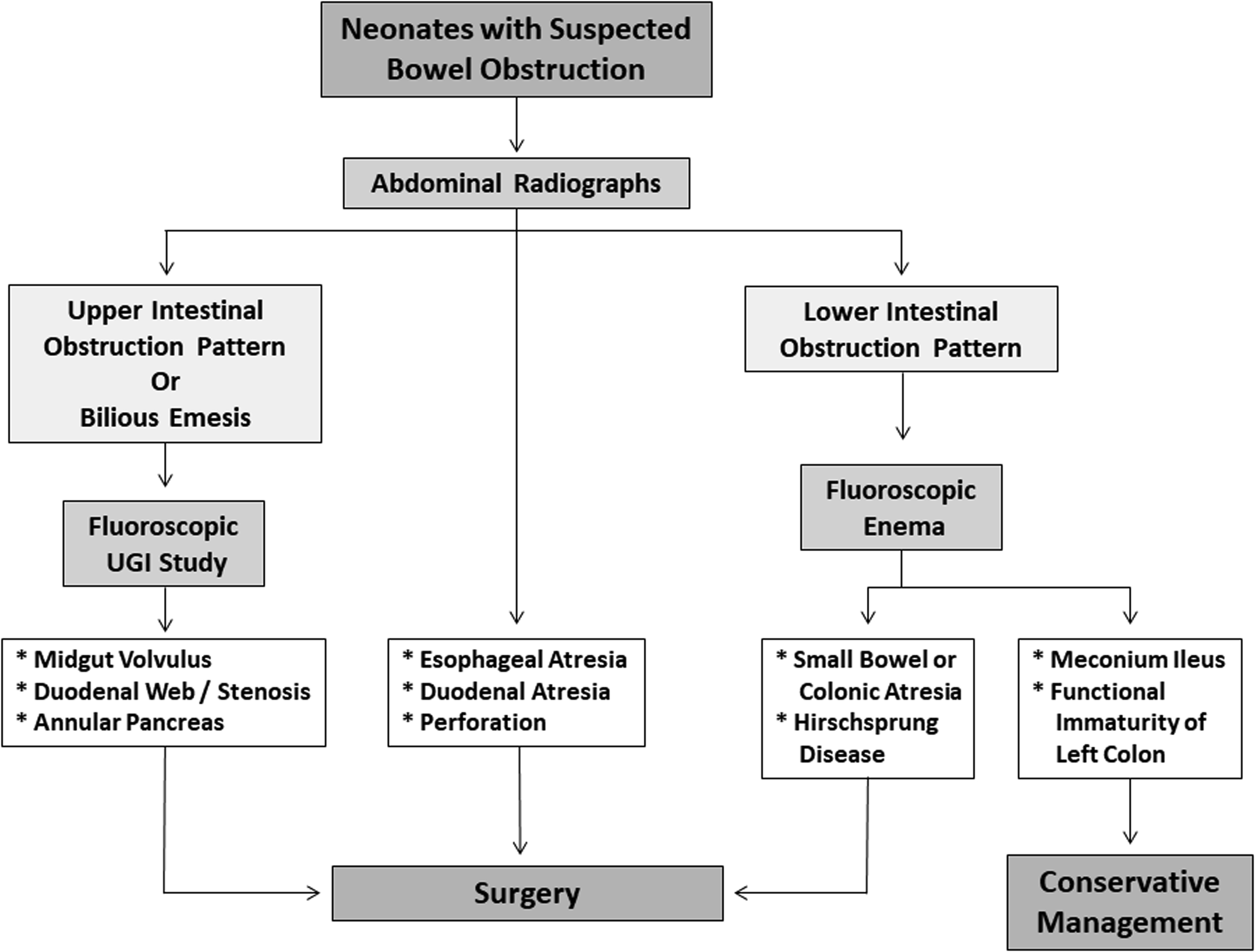

Imaging is highly useful in diagnosing and localizing pediatric bowel obstructions. In almost every case of suspected obstruction, abdominal radiographs are helpful as a first-line imaging examination in children of any age to determine (1) if there are signs of obstruction; (2) if the obstruction is in the upper or lower gastrointestinal (GI) tract; and (3) if there is evidence of bowel perforation, such as pneumoperitoneum. If perforation is suspected, obtaining subsequent upright or left lateral decubitus views is important and increases sensitivity for detecting free air to 85% and 96%, respectively. Although radiographs are an appropriate first step, their sensitivity for diagnosing a specific etiology often is lacking; therefore, additional imaging modalities may be necessary for a definitive diagnosis. A practical and evidence-based imaging algorithm ( Figs. 1 and 2 ) based on the age of the patients (neonate vs older child) can be used to help guide management.

Neonate

Following initial radiographs, if an upper tract obstruction is suspected in a neonate, a fluoroscopic upper GI imaging (UGI) series is performed next to localize and delineate the obstruction. UGI adequately characterizes duodenal stenosis, duodenal web, and jejunal atresia and can suggest a diagnosis of annular pancreas, although a proximal jejunal atresia usually is a radiographic diagnosis with a triple bubble sign. Although sensitivity and specificity are not abundant in the literature for these, UGI generally is the most appropriate and widely accepted imaging study for these diagnoses. UGI is the imaging study used most commonly for the detection of malrotation and midgut volvulus, with approximate sensitivity of 96% and 79%, respectively. The use of ultrasound (US) for diagnosis of malrotation with midgut volvulus has more variable degrees of accuracy reported in the literature. , Radiographs typically are adequate for establishing a diagnosis of esophageal or duodenal atresia due to their characteristic and nearly pathognomonic findings (discussed later).

If a lower obstruction is suspected in a neonate, fluoroscopic contrast enema is the most widely used and appropriate imaging test to evaluate for etiologies including: ileal atresia, meconium ileus, functional immaturity of the colon, colonic atresia, and Hirschsprung disease. Contrast enema has sensitivity and specificity of 70% and 83%, respectively, for Hirschsprung disease and can help with a clinical decision to perform rectal wall biopsy. When anorectal malformations are suspected, inverted or prone radiographs can suggest a distance to a rectal pouch but with relatively low sensitivity (27%). Perineal US, however, improves sensitivity to 86% and contrast colostography has a reported sensitivity of up to 100%.

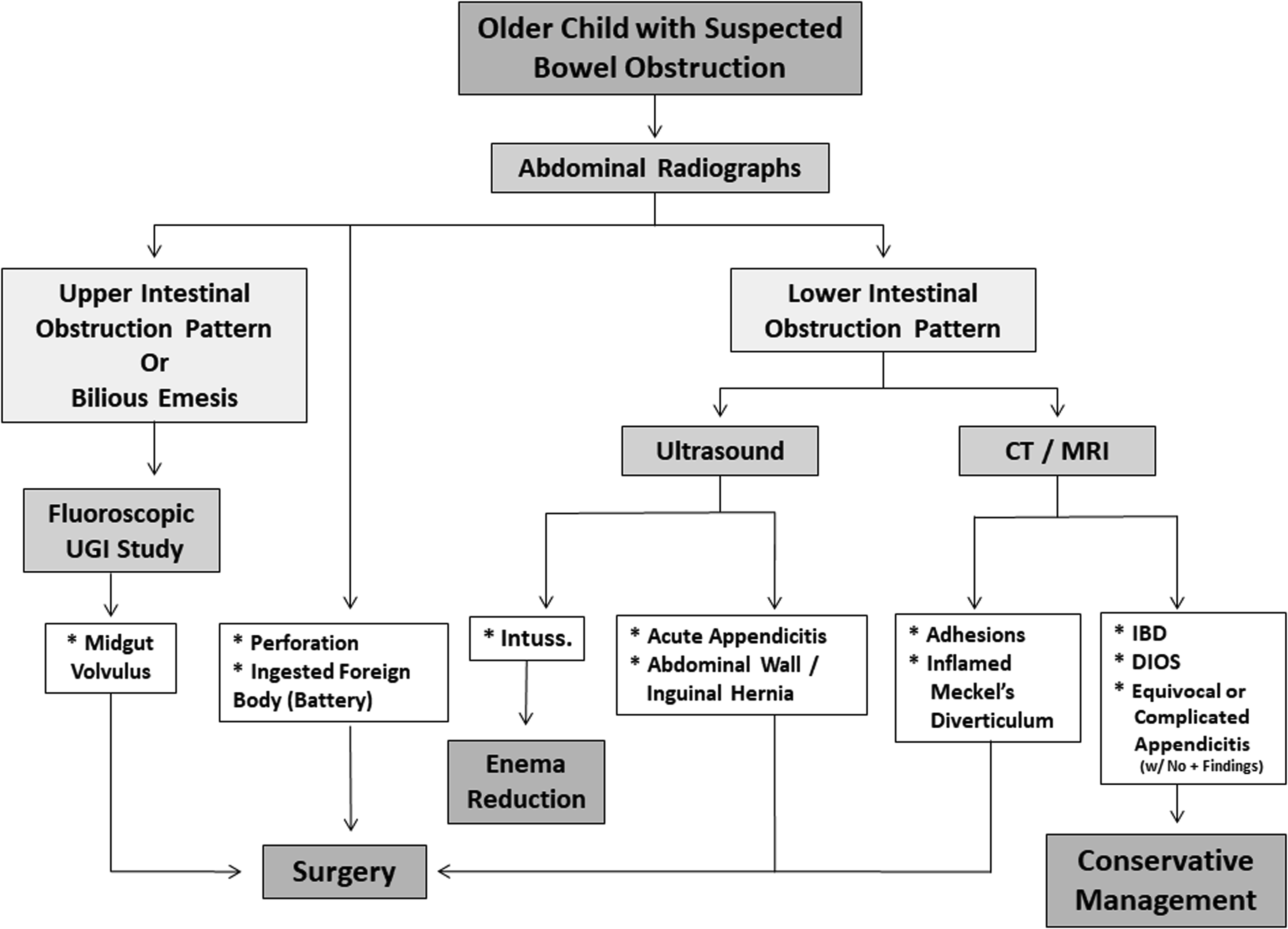

Older Child

Typically, radiographs are a useful first choice to evaluate for signs of bowel obstruction and possible bowel perforation. If bilious vomiting is present and malrotation with midgut volvulus is suspected, an emergent UGI should be performed, as discussed previously.

Many other etiologies for bowel obstruction in older children, including acute appendicitis, ileocolic intussusception, and inguinal or acquired abdominal wall hernia, can be evaluated with US. US for diagnosis of acute appendicitis has reported sensitivity and specificity of 88% and 94%, respectively, and is highly specific in cases of perforated appendicitis. , If US is equivocal, further evaluation with CT (sensitivity 96%/specificity 95%) or MR imaging (sensitivity 97%/specificity 97%) can be considered. US for diagnosis of ileocolic intussusception has a high sensitivity of 98% to 100% and specificity of 88% to 100%. Focused US of the groin can supplement physical examination and radiographs in detecting inguinal hernias, with high degrees of accuracy (95%), sensitivity (95%), and specificity (86%). Meckel’s diverticulum is diagnosed most often with imaging using a technetium pertechnetate abdominal scintigram, with reported sensitivity of 80% to 90% and specificity of 95% in pediatric patients. ,

In the setting of acute obstruction, however, US or CT may be helpful for detecting an inflamed Meckel’s diverticulum causing the obstruction. Abdominal adhesions are not often seen on imaging but signs that they may be present can be seen with US and CT with abrupt transition points or swirling of the bowel around a fixed point.

Practical imaging approach to pediatric bowel obstructions

Plain Radiography

Radiographs of the abdomen typically are the initial imaging test in children who present with abdominal pain and possible bowel obstruction. They generally are the most available, least expensive, and simplest imaging examination. Although radiographs often are not sensitive or specific as to the underlying cause of a bowel obstruction, they are excellent at showing signs of obstruction (dilated bowel loops with air-fluid levels), can help localize to an upper or lower intestinal obstruction, and show complications, such as perforation with pneumoperitoneum. Although standard supine views are helpful, decubitus, cross-table lateral, or upright views are much more sensitive for detecting pneumoperitoneum and can demonstrate air-fluid levels better.

Fluoroscopy

Contrast fluoroscopy frequently is used to diagnose and localize sites of bowel obstructions, especially in neonates and young children. UGI examinations can show causes of upper obstructions, including malrotation with midgut volvulus and duodenal stenosis, atresia, or web. Fluoroscopic enemas often reveal the cause of lower intestinal obstructions in neonates who have failed to pass meconium or in children with chronic constipation. It also is used during pneumatic reductions of ileocolic intussusceptions.

Ultrasound

US is an essential tool in the work-up of pediatric bowel obstructions. US has wide availability and a lack of ionizing radiation; offers high-resolution, real-time capability at a relatively low cost; and rarely requires sedation. It frequently is used for targeted evaluation of suspected acute appendicitis, abdominal wall and inguinal hernias, and ileocolic intussusceptions.

Computed Tomography

Computed tomography (CT) generally allows for a more comprehensive evaluation of abdominopelvic anatomy. Due to use of ionizing radiation and increased cost, however, it generally is reserved for the setting of pediatric bowel obstruction for troubleshooting when other imaging tools (such as radiographs or US) are not definitive. CT can be highly valuable in identifying specific locations and causes of bowel obstructions, such as with luminal masses; and secondary imaging findings, such as focal bowel dilatation due to abdominal adhesions.

MR Imaging

MR imaging rarely is used in the imaging work-up of bowel obstruction in the pediatric population. Although it does not use ionizing radiation, MR imaging generally is less available than other modalities, is more expensive, and usually requires sedation in infants and young children. MR imaging, however, does provide excellent soft tissue contrast resolution and may be helpful in the evaluation of bowel obstruction if a cause cannot be identified with other modalities or if more detailed imaging is needed for presurgical planning in the setting of an abdominal mass or chronic obstruction.

Nuclear Medicine

Nuclear medicine imaging is not used routinely for the work-up of acute bowel obstruction because it is relatively time-intensive, uses ionizing radiation, is less available than many other modalities (especially after normal business hours), and may not provide a specific answer in most cases. It can be useful, however, in selected clinical scenarios in the pediatric population, such as a suspected Meckel’s diverticulum.

Spectrum of bowel obstruction in infants and children

Bowel obstruction in the pediatric population can be evaluated best when a patient is categorized into either neonatal or older children groups based on the age of the patient, because the typical underlying causes and types of imaging used for the evaluation often are different.

Neonatal Bowel Obstruction

Neonatal bowel obstruction can be high or low in location depending on the underlying causes.

High intestinal obstruction

Six congenital anomalies (including esophageal atresia, duodenal atresia, duodenal web, duodenal stenosis/annual pancreas, malrotation with midgut volvulus, and jejunal atresia/stenosis) account for a majority of high intestinal obstruction in neonates.

Esophageal atresia

Esophageal atresia classically is a clinical diagnosis, with affected patients presenting with symptoms of choking, sialorrhea, or respiratory distress within the first hours of life. This disorder represents a spectrum and is usually classified based on if and where a fistulous connection between the esophagus and the trachea exists. Associated VACTERL anomalies (vertebral anomaly, anorectal atresia, cardiac lesion, tracheoesophageal fistula, renal anomaly, and limb defect) also may be present. Prenatal US or MR imaging may detect an esophageal pouch, small stomach, and polyhydramnios.

After birth, radiographs often show failure to pass an enteric tube beyond the upper esophagus to midesophagus ( Figs. 3 and 4 ). Bowel gas may be absent if there is no tracheoesophageal fistula, whereas the presence of bowel gas suggests a fistulous communication with the airway. Although timing of surgical repair often depends on the length of the gap between the proximal and distal limbs as well as other concomitant congenital anomalies, surgical repair typically occurs in the first 2 days of life. Contrast esophagram can be used to assess for recurrent fistulae and narrowing at the surgical site after surgical repair.

Duodenal atresia

Duodenal atresia is thought to occur due to complete failure of recanalization of the duodenal lumen and often presents with vomiting. Trisomy 21 can be associated and be present in up to 40% of cases. , The double bubble sign with absence of distal bowel gas classically is seen on radiographs, representing the dilated stomach and proximal duodenum, and is diagnostic ( Fig. 5 ).

Duodenal web

Duodenal web is similar to atresia but there is only partial failure of recanalization of the lumen with a residual membrane with a central pinhole, which can lead to partial or intermittent obstruction. Radiographically, it can appear similar to duodenal atresia, but distal bowel gas usually is present. Classically, a diagnosis is made on contrast fluoroscopic UGI examination, which shows partial obstruction and ballooned, windsock deformity ( Fig. 6 ) with a faint radiolucent membrane from barium filling around the membrane.

Duodenal stenosis/annular pancreas

As in duodenal atresia, duodenal stenosis, with or without annular pancreas, often shows gastroduodenal distention, but distal bowel gas is present ( Figs. 7 and 8 ). There is partial duodenal obstruction due to a stenotic duodenal segment from partial atresia or from an anomalous congenital ring of pancreatic tissue surrounding the second portion of the duodenum, or annular pancreas. UGI examination can be suggestive of a diagnosis with narrowing of the descending duodenum. CT or MR imaging may be needed to confirm the diagnosis and can demonstrate a ring of pancreatic tissue surrounding the descending duodenum.

Malrotation with midgut volvulus

In normal embryonic development, the bowel rotates counterclockwise 270° to form a broad mesenteric attachment, with the duodenojejunal junction in the left upper quadrant and the ileocecal junction in the right lower quadrant. This broad attachment prevents the bowel from twisting around its mesentery. Conversely, in malrotation, the bowel has a narrower mesenteric attachment and may twist around its vascular pedicle and cause vascular obstruction and luminal narrowing of the proximal small bowel, a surgical emergency, called midgut volvulus . Additionally, anomalous peritoneal fibrous bands, termed Ladd bands , may be present and contribute to duodenal narrowing/obstruction. Pediatric patients with malrotation may be asymptomatic but typically develop bilious emesis when midgut volvulus is present.

Abdominal radiographs often are nonspecific and may appear normal or show signs of upper intestinal obstruction. If midgut volvulus is suspected, regardless of the radiographic findings, an emergent UGI study should be performed. The classic fluoroscopic findings show a duodenum that fails to cross the midline, with twisting, or corkscrew configuration of the duodenum ( Fig. 9 ). Although typically not the modality of choice, CT and US can show evidence of midgut volvulus with abnormal relationship of the superior mesenteric artery and vein or swirling of the mesenteric vessels in the so-called whirlpool sign. Treatment is urgent surgical decompression and correction, called a Ladd procedure .

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree