Cerebellar involvement by infectious-inflammatory conditions is rare in children. Most patients present with acute ataxia, and are typically previously healthy, young (often preschool) children. Viral involvement is the most common cause and ranges from acute postinfectious ataxia to acute cerebellitis MR imaging plays a crucial role in the evaluation of patients suspected of harboring inflammatory-infectious involvement of the cerebellum and brainstem. Knowledge of the imaging features of these disorders and technical competence on pediatric MR imaging are necessary for a correct interpretation of findings, which in turn prompts further management.

Key points

- •

Infectious and inflammatory diseases of the cerebellum are rare in the pediatric age group; most patients are previously healthy preschool children presenting with an acute onset of cerebellar ataxia.

- •

Acute postinfectious cerebellar ataxia (a benign, self-limiting disease) and acute cerebellitis (a serious, potentially life-threatening disease) may represent 2 ends of a spectrum of viral involvement of the cerebellum, typically in the course of varicella infection.

- •

The cerebellum may be involved in acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, multiple sclerosis, and acute necrotizing encephalopathy, typically in the context of widespread central nervous system disease.

- •

Cerebellar abscesses are mostly otogenic in the pediatric age group; an associated dural sinus thrombophlebitis must actively be excluded.

- •

Congenital infections, mainly cytomegalovirus, may impair cerebellar development/maturation, resulting in cerebellar hypoplasia with abnormal foliation.

Introduction

The rhombencephalon, or hindbrain, is composed of the pons, cerebellum, and medulla oblongata. The term derives from the Greek rhombos, meaning a lozenge-shaped figure, whereas enkephalos means the brain. During early embryogenesis, the primary rhombencephalic vesicle divides into 2 secondary vesicles: the metencephalon (eventually forming the pons and cerebellum) and the myelencephalon (eventually forming the medulla oblongata). Rhombencephalic involvement by infectious-inflammatory conditions is rare in children. Most affected patients present acutely with ataxia, which is defined as the inability to coordinate muscle activity in the execution of voluntary movements. These children are mostly young (typically preschool) and previously healthy, although preexisting prodromal symptoms such as fever or rash, or chronic medical disorders, are sometimes recorded. Clinically, patients complain with broad-based gait, dysmetria, dysdiadochokinesia, intention tremor, dysarthria, and sometimes nystagmus, all of which progress rapidly to a nadir, which is reached within hours to 1 to 2 days of the onset.

In this clinical context, the term cerebellitis is often used loosely by clinicians to indicate that the acute onset of cerebellar ataxia likely results from primary infection or a postinfectious immune-mediated process involving the cerebellum. However, within this broad category several conditions with often different presentation, outcome, and therapeutic implications are included. The term rhombencephalitis (RE) is also often used loosely, mainly to refer to inflammatory diseases that involve primarily the brainstem; the term brainstem encephalitis is often used interchangeably with RE. The differential diagnosis of patients presenting in the emergency department with acute cerebellar ataxia includes a large group of entities, such as vascular, traumatic, metabolic, and neoplastic diseases next to infectious-inflammatory causes. More specific terminology and agreement about the usage of nomenclature is therefore desirable.

The term acute cerebellitis should be used to refer to an infection that directly affects the cerebellum, either unilaterally or bilaterally, often with abnormal magnetic resonance (MR) imaging findings and with symptoms and signs beyond those of a pure cerebellar syndrome. In contrast, the term acute postinfectious cerebellar ataxia (APCA) should be used to indicate a postinfectious (mostly viral) dysfunction, usually presenting with a pure pancerebellar syndrome and with an initially normal MR imaging scan. Despite these attempts at a correct definition, there is considerable overlap between these entities, which may represent a spectrum of disorders ranging from benign, self-limiting disease to marked swelling of the cerebellum and hydrocephalus. Confusion is also generated by other more widespread central nervous system (CNS) inflammatory disorders, such as acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) or multiple sclerosis, that can present with predominantly cerebellar clinical findings but with lesions on neuroimaging that are usually widespread. This article reviews the most common infectious and inflammatory conditions involving the cerebellum and brainstem, with a focus on the role of neuroimaging studies, particularly MR imaging scans, in the work-up of affected children.

Introduction

The rhombencephalon, or hindbrain, is composed of the pons, cerebellum, and medulla oblongata. The term derives from the Greek rhombos, meaning a lozenge-shaped figure, whereas enkephalos means the brain. During early embryogenesis, the primary rhombencephalic vesicle divides into 2 secondary vesicles: the metencephalon (eventually forming the pons and cerebellum) and the myelencephalon (eventually forming the medulla oblongata). Rhombencephalic involvement by infectious-inflammatory conditions is rare in children. Most affected patients present acutely with ataxia, which is defined as the inability to coordinate muscle activity in the execution of voluntary movements. These children are mostly young (typically preschool) and previously healthy, although preexisting prodromal symptoms such as fever or rash, or chronic medical disorders, are sometimes recorded. Clinically, patients complain with broad-based gait, dysmetria, dysdiadochokinesia, intention tremor, dysarthria, and sometimes nystagmus, all of which progress rapidly to a nadir, which is reached within hours to 1 to 2 days of the onset.

In this clinical context, the term cerebellitis is often used loosely by clinicians to indicate that the acute onset of cerebellar ataxia likely results from primary infection or a postinfectious immune-mediated process involving the cerebellum. However, within this broad category several conditions with often different presentation, outcome, and therapeutic implications are included. The term rhombencephalitis (RE) is also often used loosely, mainly to refer to inflammatory diseases that involve primarily the brainstem; the term brainstem encephalitis is often used interchangeably with RE. The differential diagnosis of patients presenting in the emergency department with acute cerebellar ataxia includes a large group of entities, such as vascular, traumatic, metabolic, and neoplastic diseases next to infectious-inflammatory causes. More specific terminology and agreement about the usage of nomenclature is therefore desirable.

The term acute cerebellitis should be used to refer to an infection that directly affects the cerebellum, either unilaterally or bilaterally, often with abnormal magnetic resonance (MR) imaging findings and with symptoms and signs beyond those of a pure cerebellar syndrome. In contrast, the term acute postinfectious cerebellar ataxia (APCA) should be used to indicate a postinfectious (mostly viral) dysfunction, usually presenting with a pure pancerebellar syndrome and with an initially normal MR imaging scan. Despite these attempts at a correct definition, there is considerable overlap between these entities, which may represent a spectrum of disorders ranging from benign, self-limiting disease to marked swelling of the cerebellum and hydrocephalus. Confusion is also generated by other more widespread central nervous system (CNS) inflammatory disorders, such as acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) or multiple sclerosis, that can present with predominantly cerebellar clinical findings but with lesions on neuroimaging that are usually widespread. This article reviews the most common infectious and inflammatory conditions involving the cerebellum and brainstem, with a focus on the role of neuroimaging studies, particularly MR imaging scans, in the work-up of affected children.

Neuroimaging: general principles

Children presenting in the emergency department with an acute onset of cerebellar ataxia are typically referred for urgent imaging studies, which may include a computerized tomography (CT) or MR imaging scan depending on several considerations, including the clinical severity, the need for sedation, and organizational issues at the individual facility. Often, the range of differential diagnosis at this initial stage is wide, and includes tumors involving the brainstem or cerebellum and potentially causing hydrocephalus, metabolic disorders, cerebrovascular causes, trauma, and intoxications; thus, the inclusion of neuroimaging studies in the initial work-up of these patients is fully justified. Furthermore, the widespread use of varicella and mumps vaccinations has significantly reduced the number of the pediatric cases of APCA. Patients presenting with acute cerebellar ataxia in the postvaccination era may be presumed to harbor significant disorder in a higher proportion of cases. However, children less than 3 years of age and with duration of ataxia of less than 3 days may represent a low-risk group in which neuroimaging can be deferred if contingent on close clinical follow-up and reassessment.

Cranial ultrasonography provides an excellent bedside examination in premature and term newborns and small infants; however, the exploration of the brain is limited to the first months of life in relation to the patency of the acoustic windows, represented by the cranial fontanelles. A recent study in preterm infants showed that the routine use of ultrasonography through the mastoid fontanelle (MF) may allow a better identification of cerebellar hemorrhages than through the anterior fontanelle ; this can easily be explained by the closer and better visualization of posterior fossa structures, both on coronal and axial planes, that can be obtained through the MF, particularly in extremely immature newborns. However, the exploration of the cerebellum remains challenging, and there are differences in the diagnosis and interpretation of cranial ultrasonography examinations according to the available ultrasonography technology and expertise.

The authors prefer MR imaging to CT because of its intrinsically higher contrast resolution and sensitivity, particularly for lesions affecting the posterior fossa, a notoriously difficult region for CT despite newer technological advances, as well as for inherent radiation issues. However, when MR imaging is unavailable or unfeasible, CT remains an important imaging modality. A helical acquisition with reformatted images in 3 planes should be obtained, and the whole brain should be studied including the craniocervical junction and cervical spine until C3. Iodinated contrast material administration is not routine, and should be performed only when there is concern for transverse-sigmoid sinus thrombosis; in this situation, only a postcontrast CT scan should be acquired in order to avoid a double dose of ionizing radiation.

MR imaging scans offer an exquisite depiction of posterior fossa structures, without the burden of ionizing radiation, and should therefore be preferred even in urgent situations whenever possible. In children, slice thickness for MR imaging should not exceed 4 mm. Three-dimensional T1-weighted sequences, and T2-weighted sequences, should be obtained along with axial or coronal fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) sequences. Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) with corresponding apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) maps are of paramount importance to pick up signs of acute cytotoxic or vasogenic edema, which may be caused by either inflammation, infection, or ischemia involving the cerebellum, whereas susceptibility-weighted imaging (SWI) is useful to identify hemorrhagic foci. Postcontrast images, obtained after the intravenous injection of 0.2 mL/kg of gadolinium chelate, are useful in the context of a suspected infectious or inflammatory causes to detect areas of blood-brain barrier damage. In addition, MR venography is important to rule out a dural sinus thrombosis.

Acute cerebellitis

Acute cerebellitis (AC) represents the most severe end of the spectrum of infectious-inflammatory disorders of the cerebellum, and may cause long-term cognitive and behavioral impairment. The cause is often unknown, although a well-known association with viral infections exists, prominently including varicella and other viruses such as influenza, rotavirus, human herpesvirus 7, and Epstein-Barr virus, as well as with Mycoplasma pneumoniae . Pathologic reports are scarce in the literature; available data suggest an edematous process with lymphocytic and eosinophilic infiltration but no evidence of demyelination, which differentiates AC from ADEM. Clinical findings are variable, and depend on the severity of cerebellar involvement. Fulminant cases, causing sudden death from acute cerebellar herniation, have been reported. Cerebellar swelling may cause increased intracranial pressure and hydrocephalus, overshadowing the manifestations of cerebellar dysfunction; patients may complain of irritability, headache, photophobia, nuchal rigidity, and vomiting, with ensuing alteration of sensorium, seizures, focal neurologic deficits, and possibly fever. Less severe cases present with either unilateral or bilateral cerebellar symptoms and signs. Cerebrospinal fluid examination may be hazardous because of the risk of cerebellar herniation. When available, findings may include lymphocytic pleocytosis and protein level increase.

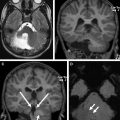

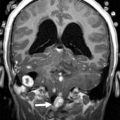

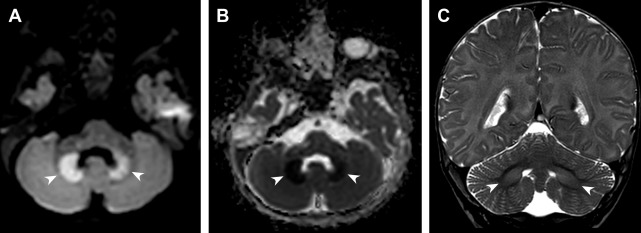

MR imaging scans may show unilateral ( Fig. 1 ) or bilateral ( Fig. 2 ) cerebellar swelling, with T2 and FLAIR hyperintensity of the cerebellar cortex and/or subcortical and deep white matter. There may be pial contrast enhancement along cerebellar folia. In the acute stage, DWI may show increased signal with corresponding hypointensity on ADC maps, consistent with restricted water diffusion ( Fig. 3 ). There have been reports on the use of perfusion-weighted imaging, showing decreased relative cerebral blood flow in the affected area, and of proton MR spectroscopy ( 1 H-MRS) showing increased choline/creatine (Cho/Cr) and reduced N -acetylaspartate/creatine (NAA/Cr) ratios; presence of additional peaks, such as succinate or acetate, has been considered a strong imaging indicator of an infectious cause. In the most severe cases, tonsillar herniation and hydrocephalus with periventricular edema are encountered. Unilateral cerebellar involvement (so-called hemicerebellitis) may be so severe as to mimic tumor. In AC, MR imaging signal changes are confined to the cerebellum, unlike other disorders such as ADEM and multiple sclerosis. MR imaging findings may normalize or evolve into cerebellar atrophy on long-term follow-up. CT scan is not sensitive to subtle alterations in the cerebellum; however, in an acute context it may be useful to display cerebellar swelling, downward tonsillar ectopia, and hydrocephalus if MR imaging is not readily available.

Acute postinfectious cerebellar ataxia

APCA is the most common cause of acute ataxia in children, accounting for about 30% to 50% of cases. Patients typically present between 2 and 5 years of age with an acute onset of gait alterations and/or inability to perform coordinated movements; these symptoms usually regress within 72 hours. The prognosis is good with a high rate of spontaneous resolution and treatment is rarely indicated. APCA mainly occurs in the aftermath of infection, most notably varicella (about 75% of all cases), mumps, M pneumoniae , Epstein-Barr virus, and other nonspecific viral infections, with a latency of a few days to 2 weeks of the prodromal illness.

In patients with APCA, neuroimaging studies including MR imaging with DWI sequences typically show no abnormalities ; evidence of abnormality involving the cerebellum should redirect classification to AC.

Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis

ADEM is an immunologically mediated inflammatory disease of the CNS involving a first, usually monophasic, episode of inflammatory demyelination with polyfocal neurologic signs implicating involvement of multiple sites of the CNS. Patients present with a rapid onset of encephalopathy and motor and/or sensory deficits with brainstem signs and symptoms and, in most cases, ataxia. Presence of encephalopathy (defined as altered behavior or consciousness) is a required criterion for ADEM. Most patients with ADEM present in the aftermath (usually 1–3 weeks) of viral infection or, rarely, vaccination.

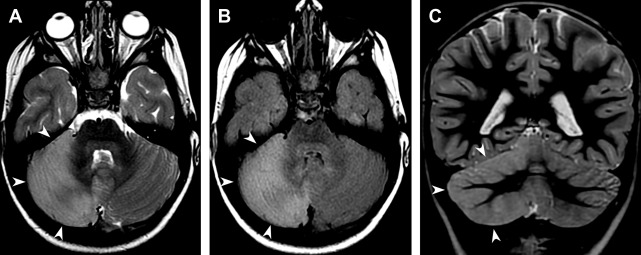

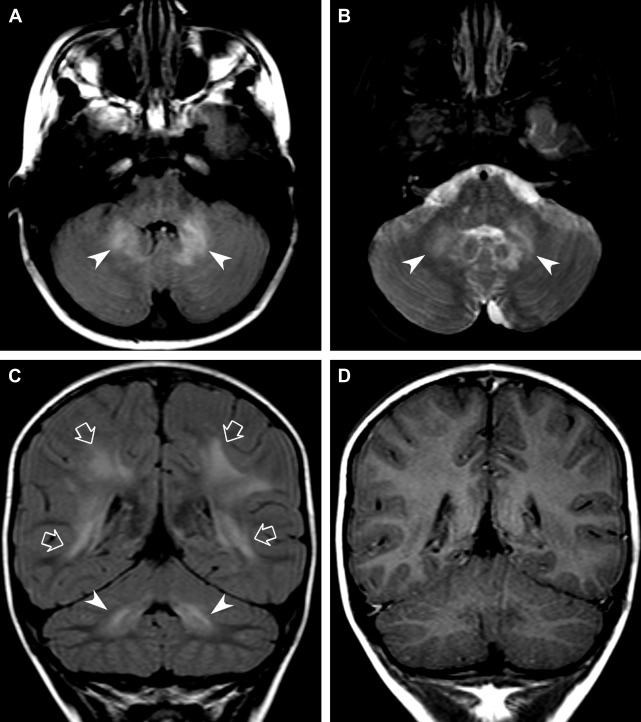

Unlike AC, ADEM typically is characterized by widespread lesions involving not just the cerebellum but also the supratentorial brain, brainstem, and spinal cord. MR imaging findings typically include multiple, asymmetrically distributed, poorly marginated, hyperintense areas on T2-weighted and FLAIR images, whereas unenhanced T1-weighted images are usually inconspicuous unless the lesions are very large, in which case faint hypointensity is seen. Contrast enhancement is variable and, in our personal experience, extremely uncommon. In typical cases, there are multiple lesions that involve the white matter, the deep gray matter nuclei, and sometimes the cerebral cortex. Involvement of the infratentorial compartment is seen in greater than 50% of cases. The brainstem, middle cerebellar peduncles, and cerebellar white matter may be involved ( Fig. 4 ). Especially in the brainstem, lesions may be large and tumefactive, indicating prevalent vasogenic edema as confirmed by increased ADC values on DWI sequences.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree