Procedure

Indication

Spinal decompression and reconstruction

Progressive myelopathy or radiculopathy resulting from compression of neural structures (e.g., from intervertebral disk herniation, osteophyte, spondylolisthesis, ligamentous hypertrophy)

Microvascular decompression

Classical trigeminal, glossopharyngeal, or nervus intermedius neuralgia (i.e., paroxysmal, lancinating pain)

Spinal Decompressive and Reconstructive Procedures

This group of procedures encompasses a range of operations aimed at decompression of the spinal cord and spinal nerve roots for the treatment of structural abnormalities that result in neurological deficit or intractable pain. Procedures in this category include cervical, thoracic, and lumbar diskectomy, laminectomy, and spinal fusion. They are performed routinely in the practice of general neurosurgery with minimal morbidity and mortality and – provided treatment is directed at a structural abnormality that is concordant with the pain syndrome – are for the most part quite successful in relieving axial and/or radicular pain resulting from the structural abnormality. The discussion of these procedures is beyond the scope of this chapter, and the interested reader is referred to any of a number of general neurosurgical textbooks for a more detailed treatment of these operations and outcomes.

Microvascular Decompression

Microvascular decompression is one of the most important techniques for the treatment of intractable trigeminal neuralgia, glossopharyngeal neuralgia, and nervus intermedius neuralgia [1, 2]. It is indicated for the treatment of classical neuralgia (paroxysmal, lancinating pain, often described as “electrical shocks”) that is refractory to pharmacological treatment. It is most appropriate for healthy patients, generally under the age of 65 or 70, with no medical contraindications to craniotomy.

The rationale of microvascular decompression is to eliminate compression of the affected cranial nerve by a blood vessel (usually an artery), which generally occurs near the entry of the nerve into the brainstem. Microvascular decompression has the advantage of the absence of a postoperative sensory deficit, which is an obligate outcome of percutaneous or open ablative procedures (e.g., radiofrequency rhizotomy or ganglionectomy for trigeminal neuralgia). Early pain relief is achieved in more than 90 % of patients. Pain may recur over the course of months or years, but microvascular decompression is regarded generally as providing the most durable pain relief of the various procedures, and most patients obtain lasting pain relief [1, 2]. Microvascular decompression is much less successful in treating atypical facial pain (i.e., constant, burning pain, typically not involving a clear trigeminal sensory distribution). In general, the less the degree of paroxysmal pain and the greater the degree of constant, burning, dysesthetic pain in a given individual, the less likely a good long-term outcome will be achieved with surgical intervention [3].

Ablative Therapies

Ablative therapies are often viewed as treatments of last resort for intractable pain, but in some instances, they remain the procedures of choice and should not be forgotten or overlooked by pain care providers. Important examples include dorsal root entry zone (DREZ) lesioning for treatment of phantom-limb pain following spinal nerve root avulsion or “end-zone” pain arising from spinal cord injury and cordotomy, which may be preferable to intrathecal analgesic administration for the treatment of cancer-related pain in a patient with a short life expectancy.

Ablative therapies have been developed which target almost every level of the peripheral and central nervous system: eripheral techniques that interrupt or alter nociceptive input into the spinal cord (e.g., neurectomy, ganglionectomy, rhizotomy), spinal interventions that alter afferent input or rostral transmission of nociceptive information (e.g., DREZ lesioning, cordotomy, myelotomy), and supraspinal intracranial procedures that may interrupt transmission of nociceptive information (e.g., mesencephalotomy, thalamotomy) or influence perception of painful stimuli (e.g., cingulotomy).

Ablative therapies tend to be most appropriate for the treatment of nociceptive pain rather than neuropathic pain. Neuropathic pain that is intermittent, paroxysmal, or evoked (e.g., allodynia and hyperpathia) may improve after an ablative procedure, but continuous, dysesthetic neuropathic pain tends to respond much less favorably in long-term follow-up [4]. The ablative therapies are summarized along with their primary indications in Table 48.2.

Table 48.2

Ablative procedures and their primary indications

Procedure | Indication |

|---|---|

Sympathectomy | Visceral, cancer-related pain |

Neurectomy | Identifiable neuroma following peripheral nerve injury (e.g., following limb amputation); meralgia paresthetica; inguinal pain syndromes (e.g., post-herniorrhaphy pain) |

Dorsal rhizotomy/ganglionectomy | Cancer-related trunk/abdominal pain |

Cranial nerve rhizotomy | Classical trigeminal and glossopharyngeal neuralgia when microvascular decompression is contraindicated |

C2 ganglionectomy | Occipital neuralgia |

DREZ lesioning | Localized neuropathic pain following spinal nerve root avulsion; “end-zone” pain following spinal cord injury |

Cordotomy | Cancer-related pain below mid- to low cervical dermatomes |

Myelotomy | Cancer-related abdominal, pelvic, perineal, or lower extremity pain |

Sympathectomy

Sympathectomy is indicated for the treatment of visceral pain associated with certain cancers [5, 6]. It can alleviate non-cancer pain such as that associated with vasospastic disorders or sympathetically maintained pain (when sympathetic blocks reliably relieve the pain), but it has generally fallen into disfavor as a treatment for intractable pain of nonmalignant origin because of inconsistent results [5–8]. Some data indicate that SCS provides better long-term outcomes with lower morbidity and SCS may replace sympathectomy in the treatment of sympathetically maintained pain of non-cancer origin [9]. Sympathectomy is commonly and successfully used in the treatment of intractable hyperhidrosis.

Neurectomy

Neurectomy may be useful in individuals who develop pain following peripheral nerve injury, including that associated with limb amputation. If an identifiable neuroma is the cause of pain, its resection can provide significant relief [10]. In the absence of an identifiable neuroma, neurectomy is unlikely to provide pain relief. In this regard, neurectomy is not useful for treatment of nonspecific stump pain after amputation, and it is not generally useful for the treatment of other nonmalignant peripheral pain syndromes. The utility of neurectomy is limited because pain arising from a pure sensory nerve is uncommon, and sectioning of mixed sensory-motor nerves is associated with significant risk of neurologic deficit and resultant functional impairment. There may be several exceptions to this rule. For example, section of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve has been reported to provide long-lasting relief of meralgia paresthetica [11], and section of the ilioinguinal and/or genitofemoral nerves has been reported to provide relief of certain inguinal pain syndromes (e.g., post-herniorrhaphy pain) in properly selected individuals [12].

Dorsal Rhizotomy/Ganglionectomy

Dorsal rhizotomy and ganglionectomy serve similar purposes in denervating somatic and/or visceral tissues, but ganglionectomy may produce more complete denervation than can be accomplished by dorsal rhizotomy. Some afferent fibers enter the spinal cord through the ventral root [13] and are not affected by dorsal rhizotomy. In contrast, ganglionectomy effectively eliminates input from dorsal and ventral root afferent fibers by removing their cell bodies, which are located within the dorsal root ganglion.

Rhizotomy and ganglionectomy can be used to treat pain in the trunk or abdomen. Neither procedure is useful for treatment of pain in the extremities unless function of the extremity is already lost because denervation removes proprioceptive as well as nociceptive input and produces a functionless limb. Limited denervation (e.g., a single level) does not generally provide adequate pain relief because segmental innervation of dermatomes overlaps with adjacent levels. Therefore, these procedures typically must be performed at several adjacent spinal levels. Multilevel denervation increases the sensory loss and risk of functional impairment of an extremity.

These procedures are most useful for the treatment of cancer-related pain, as non-cancer pain does not improve consistently [14, 15]. When used for treatment of neuropathic pain (e.g., postherpetic neuralgia of the trunk), lancinating, paroxysmal, or evoked pain may improve but continuous dysesthetic pain does not typically improve. In the setting of cancer, these procedures can be useful for thoracic or abdominal wall pain; for perineal pain in patients with impaired bladder, bowel, and sexual function; or for the treatment of pain in a functionless extremity. Multiple sacral rhizotomies can be performed (e.g., to treat pelvic pain from cancer) by passing a ligature around the thecal sac below S1 [16].

Cranial Nerve Rhizotomy

Rhizotomy is especially useful as a treatment of cranial neuralgias, especially trigeminal and glossopharyngeal neuralgia [17, 18]. Classical trigeminal and glossopharyngeal neuralgia are unique among neuropathic pain syndromes in their uniformly good response to ablative procedures. This reflects the general utility of ablative techniques in relieving lancinating, paroxysmal pain. In contrast, atypical facial pain syndromes (constant, burning, dysesthetic pain) do not improve with ablative techniques and may be worse following denervation by rhizotomy or other ablative techniques, either from worsening of the pain, per se, or superimposition of potentially unpleasant sensory loss on the original pain.

Percutaneous trigeminal rhizotomy can be accomplished with thermal radiofrequency (RF), glycerol injection, or balloon compression. These techniques are performed on an outpatient basis, are well tolerated, and have high success rates in relieving paroxysmal pain of cranial neuralgias. Early pain relief is almost universal, but pain can recur over months or years (in which case the same procedure or another surgical treatment can be offered) [18]. These techniques are especially useful in treating elderly, medically infirm patients who are not good candidates for craniotomy for microvascular decompression of a cranial nerve. Postoperative sensory deficit is an obligate outcome of successful rhizotomy, so candidates should be counseled accordingly. Postoperative sensory loss may render this procedure undesirable for treatment of pain around the eye because corneal sensory loss may lead to keratitis and impaired vision. Open rhizotomy (i.e., via craniotomy or craniectomy) is usually performed for treatment of glossopharyngeal and nervus intermedius neuralgia and may be useful for treatment of some trigeminal neuralgias.

Stereotactic radiosurgery rhizotomy for the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia is an alternative to percutaneous or open rhizotomy or microvascular decompression for some individuals [19]. Radiosurgery is performed on an outpatient basis as a single procedure. In contrast to percutaneous rhizotomy and other surgical treatments for cranial neuralgias, which have a high likelihood of providing immediate postoperative pain relief, pain relief may not occur for several weeks following radiosurgical treatment. Radiosurgery is, therefore, not appropriate for individuals with severe acute pain that cannot be controlled adequately with medications. Pain may recur over months or years in some patients, but relief is maintained in many patients [17, 18]. Unlike percutaneous or open rhizotomy, sensory loss after radiosurgery is uncommon. Radiosurgery is most useful for individuals who desire a relatively noninvasive treatment and whose pain is sufficiently well controlled that they can tolerate the post-procedure delay in pain relief.

C2 Ganglionectomy

C2 ganglionectomy is indicated for the treatment of occipital neuralgia. It is especially effective for individuals with posttraumatic occipital neuralgia who have no migraine component to their headache [20]. Pain relief may be comparable to that achieved with occipital nerve stimulation (see Chaps. 40 and 47) but without the need for implanted devices and long-term follow-up.

Dorsal Root Entry Zone (DREZ) Lesioning

DREZ lesioning of the spinal cord (for trunk or extremity pain) [21–23] or nucleus caudalis (for facial pain) [22, 24] can provide significant relief of neuropathic pain in properly selected individuals. The rationale of DREZ lesioning is to disrupt input into and outflow from the superficial layers of the spinal cord dorsal horn, which are the sites of termination of afferent nociceptive fibers and sites of origin of some of the nociceptive fibers that ascend within the spinal cord. DREZ lesioning may also disrupt spontaneous abnormal activity and hyperactivity that develops in spinal cord dorsal horn neurons in the setting of neuropathic pain.

DREZ lesioning is best reserved for localized pain with a neuropathic component. Certain types of cancer pain can be treated effectively with DREZ lesioning (e.g., neuropathic arm pain associated with Pancoast tumor). The most successful applications are related to treatment of neuropathic pain arising from spinal nerve root avulsion (cervical or lumbosacral) and “end-zone” or “boundary” pain following spinal cord injury. These pain syndromes sometimes respond to spinal cord stimulation or intrathecal drug infusion, but DREZ lesioning can provide a similar result without the need for long-term maintenance required by an augmentative device.

DREZ lesioning has been used for the treatment of other neuropathic pain syndromes (e.g., postherpetic neuralgia), but good pain relief is not achieved consistently. DREZ lesioning of nucleus caudalis can provide relief of deafferentation pain affecting the face (including postherpetic neuralgia), but outcomes are inconsistent. It is less helpful for facial pain of peripheral origin (e.g., traumatic trigeminal neuropathy). As with other ablative procedures, DREZ lesioning is most effective for relieving paroxysmal or evoked neuropathic pain rather than continuous neuropathic pain [23].

Cordotomy

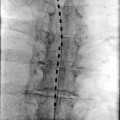

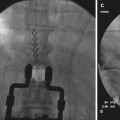

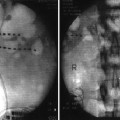

Cordotomy can be an effective method of pain control, especially when pain is related to malignancy, and especially for individuals with short life expectancies for whom it is difficult to justify the costs of implantation of drug infusion systems. The rationale of cordotomy is to disrupt nociceptive afferent fibers ascending in the spinothalamic tract in the anterolateral quadrant of the spinal cord. Cordotomy offers the advantage, compared to neuraxial analgesic administration, of being a onetime procedure with no required long-term follow-up or maintenance. This is important for individuals who may find it difficult to return to a medical facility for refilling of an infusion system or for whom costs of ongoing medical care can become burdensome. Cordotomy is used most commonly for the treatment of cancer-related pain below mid- to low cervical dermatomes. It is not generally used for treatment of patients with pain of non-cancer origin because pain typically recurs over months to years in patients with long life expectancies, and there is significant risk of post-cordotomy dysesthesias or neurological complication [25]. Cordotomy can be performed as an open [25] or closed (percutaneous) [26, 27] procedure. Percutaneous techniques are less invasive, but open techniques remain viable options because most surgeons lack the expertise and equipment required for percutaneous procedures.

Pain relief varies with pain characteristics and location. Laterally located pain responds better than midline or axial pain (e.g., visceral pain). Midline and axial pain may require bilateral procedures to achieve pain relief. Lancinating, paroxysmal neuropathic pain and evoked (allodynic or hyperpathic) pain that sometimes occurs following spinal cord injury or as part of peripheral neuropathic pain syndromes can improve following cordotomy, but continuous neuropathic pain does not improve [26].

There is a significantly greater risk of complication with bilateral procedures, including weakness, bladder, bowel, and sexual dysfunction, and respiratory depression (if the procedure is performed bilaterally at cervical levels) [25, 26]. Bilateral percutaneous cervical cordotomies are usually staged at least 1 week apart to reduce the likelihood of a serious complication. The risk of respiratory depression subsequent to a unilateral high cervical procedure mandates that pulmonary function be acceptable on the contralateral side. For example, a patient who has undergone a previous pneumonectomy for lung cancer should not be subject to cordotomy that would compromise pulmonary function on the side of the remaining lung [26].