, Joungho Han2, Man Pyo Chung3 and Yeon Joo Jeong4

(1)

Department of Radiology Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea, Republic of (South Korea)

(2)

Department of Pathology Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea, Republic of (South Korea)

(3)

Department of Medicine Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea, Republic of (South Korea)

(4)

Department of Radiology, Pusan National University Hospital, Busan, Korea, Republic of (South Korea)

Abstract

Solitary pulmonary nodules (SPNs) are defined as focal, round, or oval areas of increased opacity in the lung with diameters of ≤3 cm [1] (Fig. 1.1). The lesion is not associated with pneumonia, atelectasis, or lymphadenopathy.

Solitary Pulmonary Nodule (SPN), Solid

Definition

Solitary pulmonary nodules (SPNs) are defined as focal, round, or oval areas of increased opacity in the lung with diameters of ≤3 cm [1] (Fig. 1.1). The lesion is not associated with pneumonia, atelectasis, or lymphadenopathy.

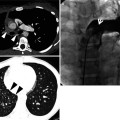

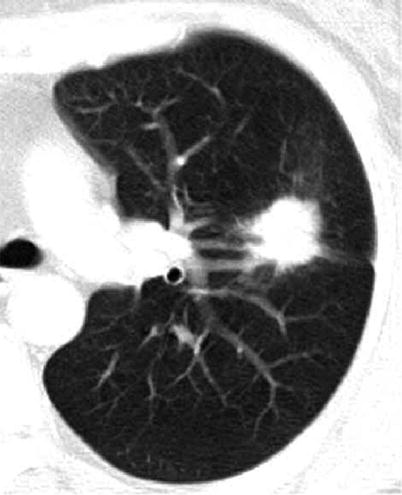

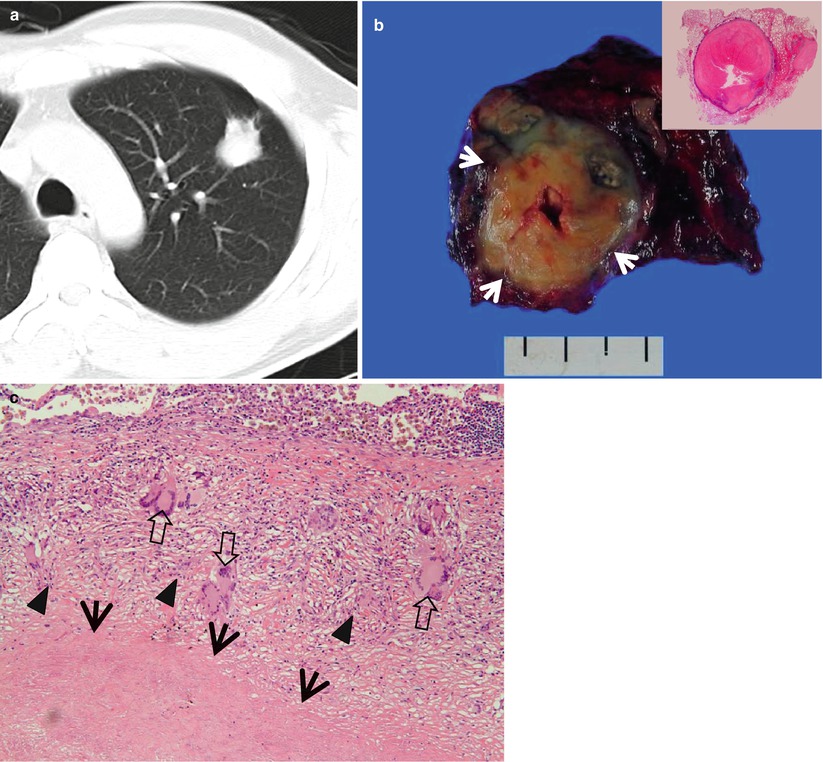

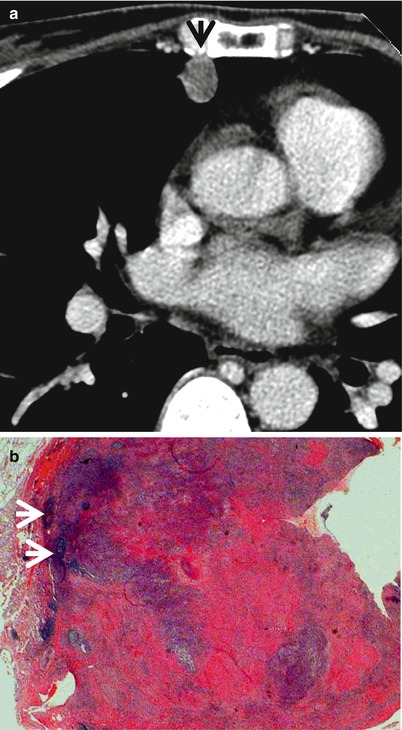

Fig. 1.1

A lung nodule representing lung adenocarcinoma with acinar- and papillary-predominant subtypes in a 52-year-old woman. Thin-section (2.5-mm section thickness) CT scan obtained at level of tracheal carina shows a 22-mm-sized nodule with lobulated and spiculated margin in the left upper lobe

Particularly when the nodule is less than 10 mm in diameter, it may be called small nodule (Fig. 1.2). With its diameter less than 3 mm, it may be called micronodule [2].

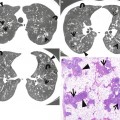

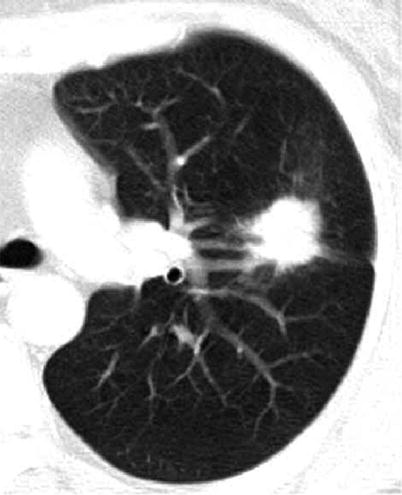

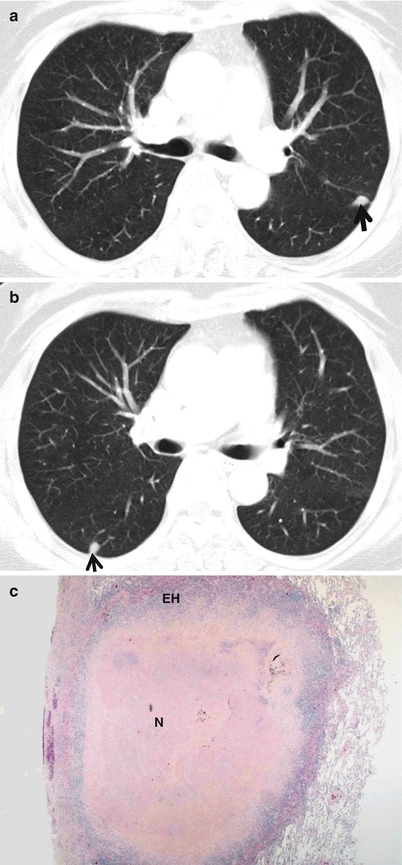

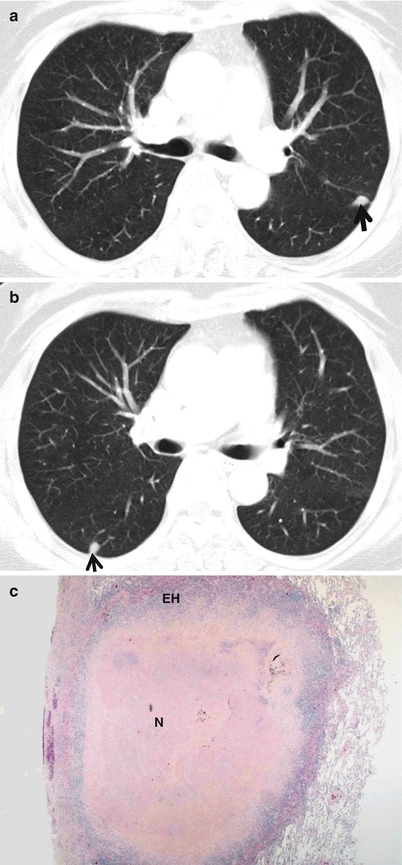

Fig. 1.2

Small nodules representing rheumatoid nodules in a 70-year-old woman with rheumatoid arthritis. (a, b) CT scans (5.0-mm section thickness) obtained at levels of main bronchi (a) and bronchus intermedius (b), respectively, show subcentimeter nodules (arrows) in the left upper lobe and right lower lobe. (c) Low-magnification (×2) photomicrograph of biopsy specimen obtained from right lower lobe nodule demonstrates central necrosis (N) area surrounded by a rim of epithelioid histiocytes (EH) and fibrous tissue

Diseases Causing the Pattern

The most common cause is malignant tumor including lung cancer (Fig. 1.3), carcinoid (Fig. 1.4), bronchus–associated lymphoid tissue (BALT) lymphoma (Fig. 1.5), and a solitary metastasis to the lung. Benign tumors are granuloma (Fig. 1.6), hamartoma (Fig. 1.7), sclerosing hemangiomas (Fig. 1.8), inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (IMT, inflammatory pseudotumor) (Fig. 1.9), rheumatoid nodule (Fig. 1.2), parasitic infection (Paragonimus westermani), and nodule in antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated granulomatous vasculitis (former Wegener’s granulomatosis) (Fig. 1.10) (Table 1.1).

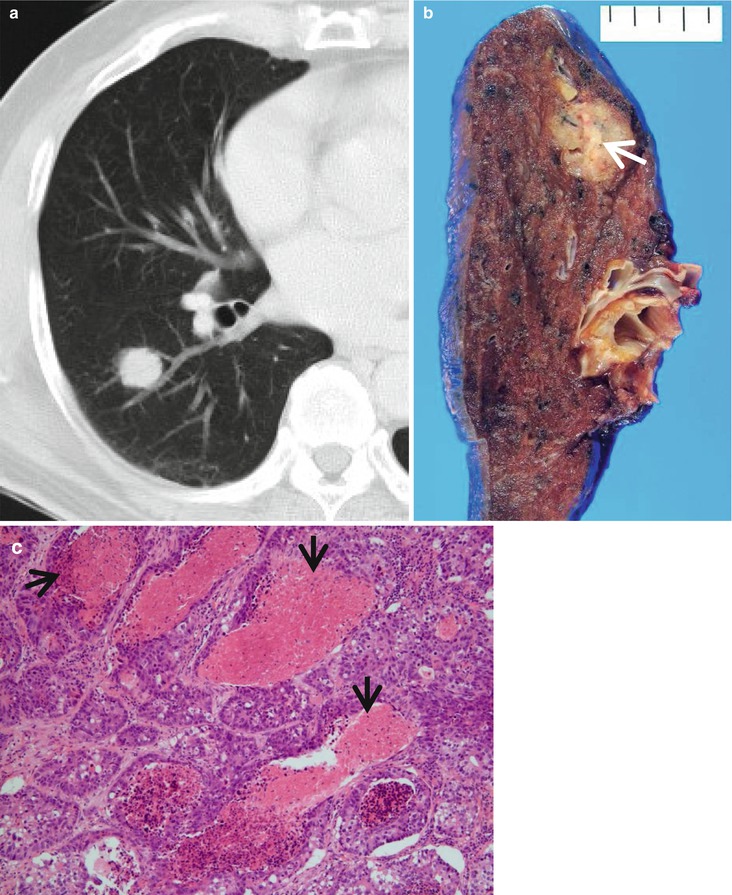

Fig. 1.3

High-grade lung adenocarcinoma simulating a metastatic nodule from a colon cancer in a 65-year-old man. (a) CT scan (5.0-mm section thickness) obtained at level of truncus basalis shows a 21-mm-sized nodule in superior segment of the right lower lobe. (b) Gross pathologic specimen demonstrates a yellowish-gray round nodule with yellow necrotic spots (arrow). (c) High-magnification (×200) photomicrograph discloses high-grade, enteric-type lung adenocarcinoma showing glandular structures with multifocal dirty necrosis (arrows) simulating metastatic colon adenocarcinoma

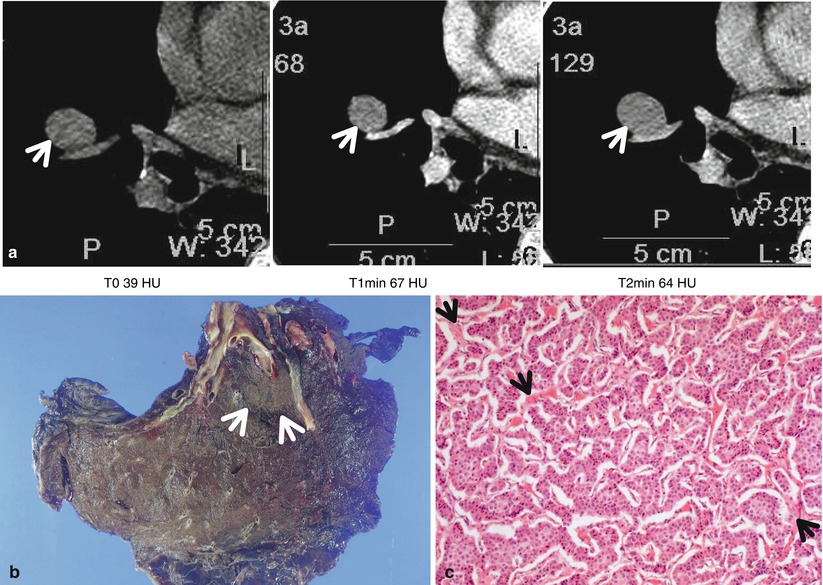

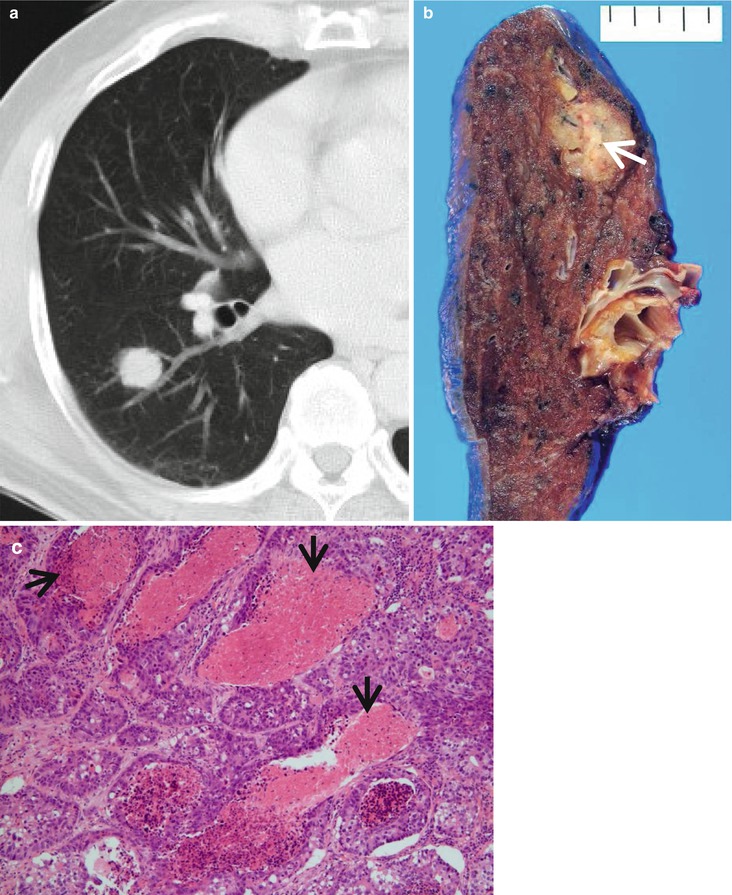

Fig. 1.4

Typical carcinoid tumor showing high and early enhancement in a 58-year-old man. (a) Dynamic CT scans obtained at level of right middle lobar bronchus takeoff show an 18-mm-sized well-defined nodule (arrows) in the right middle lobe. Nodule depicts high enhancement (39 HU, 67 HU, and 64 HU; before, at 1 min, and at 2 min after contrast-medium injection, respectively). (b) Gross pathologic specimen demonstrates a well-defined nodule (arrows) in the right middle lobe adjacent to the segmental bronchus. (c) High-magnification (×100) photomicrograph of right lower lobectomy specimen discloses neoplastic cells grouped in small nests separated by numerous thin-walled vascular stroma (arrows)

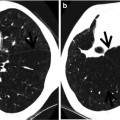

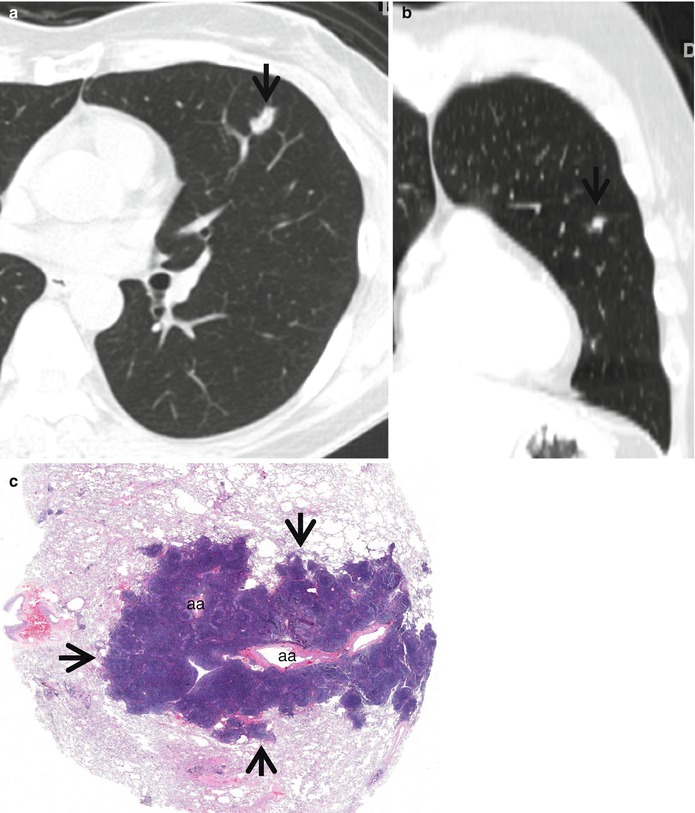

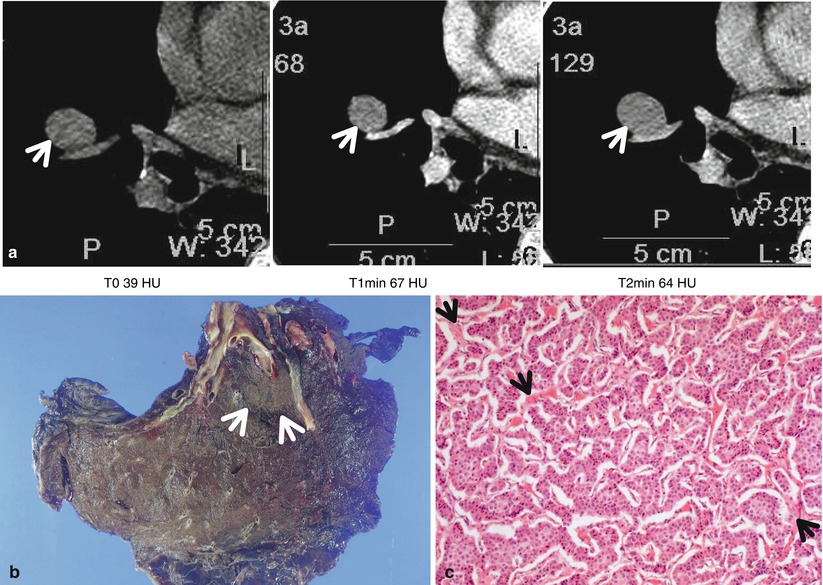

Fig. 1.5

Bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue (BALT) lymphoma in a 51-year-old woman. (a, b) Transverse (a, 2.5-mm section thickness) and coronal reformatted (b) CT scans, respectively, show a 13-mm-sized polygonal nodule (arrows) in lingular division of the left upper lobe. Lesion has internal CT air-bronchogram sign. (c) Low-magnification (×2) photomicrograph of biopsy specimen obtained from left upper lobe nodule demonstrates lymphoepithelial lesions (arrows) surrounding the pulmonary arteries (aa) and their accompanying bronchi (lumina have been compressed and collapsed)

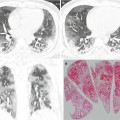

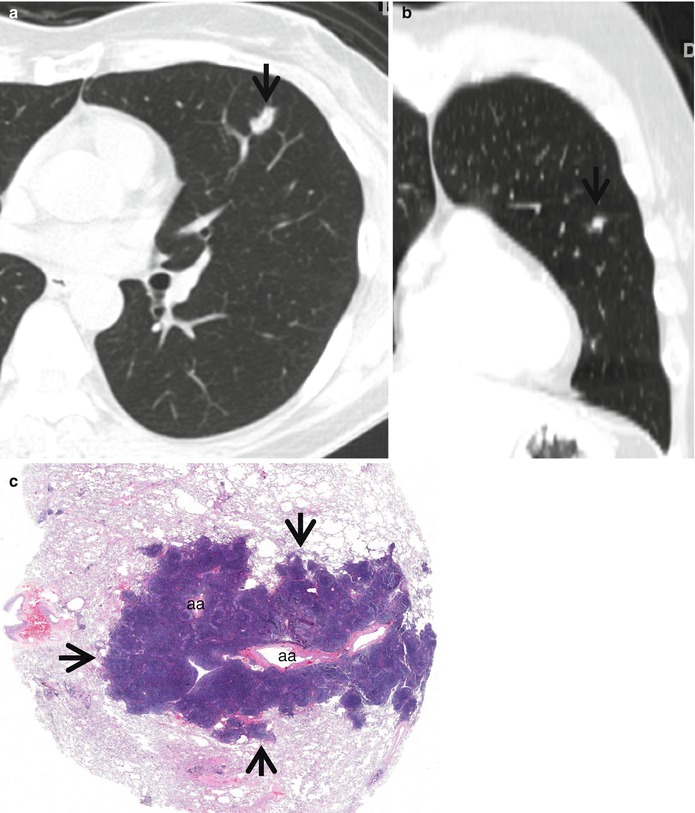

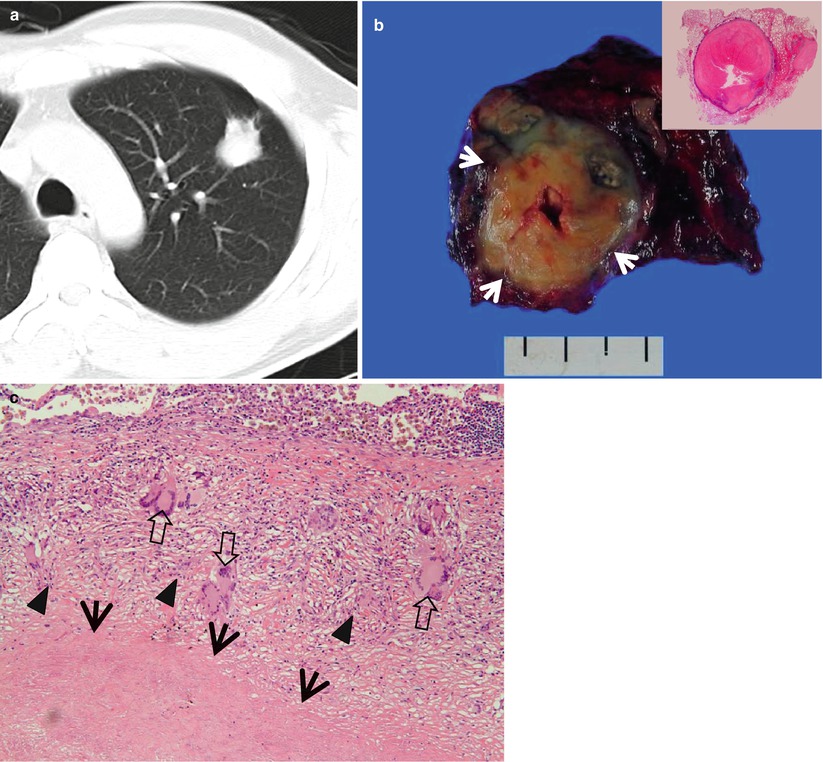

Fig. 1.6

Tuberculoma in a 47-year-old woman. (a) CT scan (5.0-mm section thickness) obtained at level of aortic arch shows a 27-mm-sized nodule in anterior segment of the left upper lobe. (b) Gross pathologic specimen demonstrates a well-defined round nodule (arrows). Inset: central caseation necrosis and peripheral epithelioid histiocytes, multinuclear giant cells, and collagenous tissue. (c) High-magnification (×100) photomicrograph discloses a focus of a necrotic lung (arrows) surrounded by a layer of epithelioid histiocytes (arrowheads) and scattered giant cells (open arrows). Numerous lymphocytes and collagenous tissues are seen adjacent to granulomatous inflammation

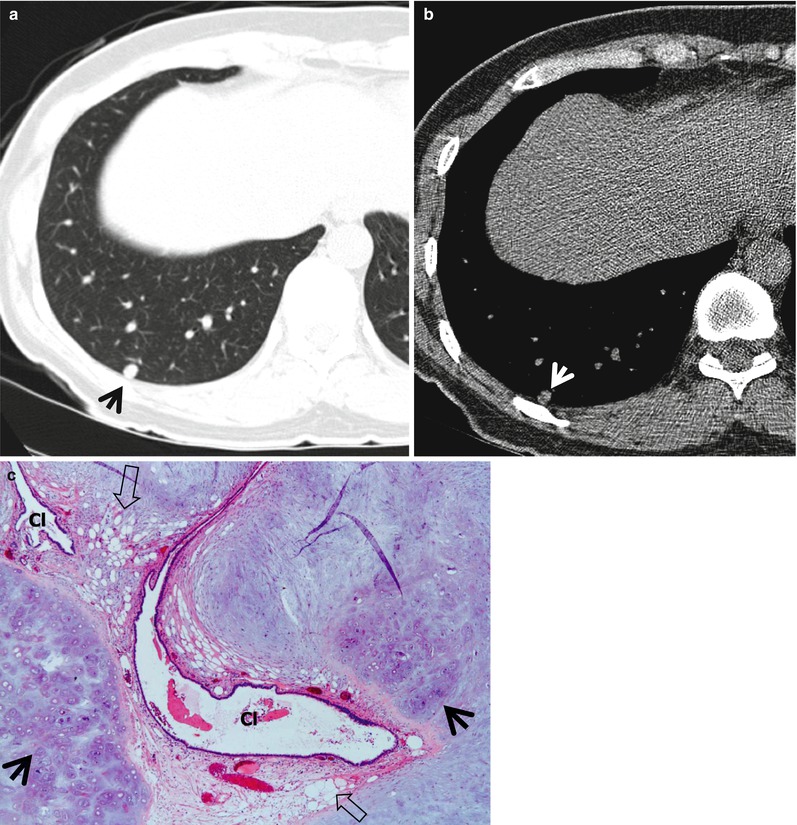

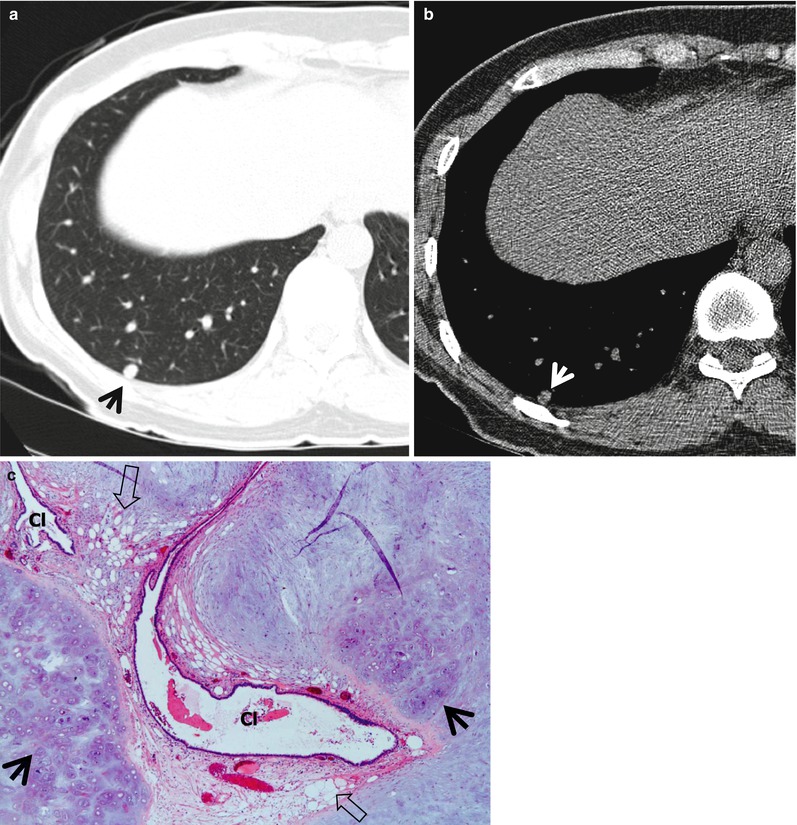

Fig. 1.7

Chondroid hamartoma in a 40-year-old woman. (a, b) Lung (a) and mediastinal (b) window images of CT scan (5.0-mm section thickness) obtained at level of lover dome show an 8-mm-sized well-defined nodule (arrows) in posterior basal segment of the right lower lobe. Please note fat and calcification attenuation areas within nodule. (c) Low-magnification (×10) photomicrograph of wedge resection from the right lower lobe demonstrates islands of mature chondroid (arrows) and adipocytic (open arrows) tissues. Also note entrapped bronchiolar epithelial cleft (Cl) within lesion

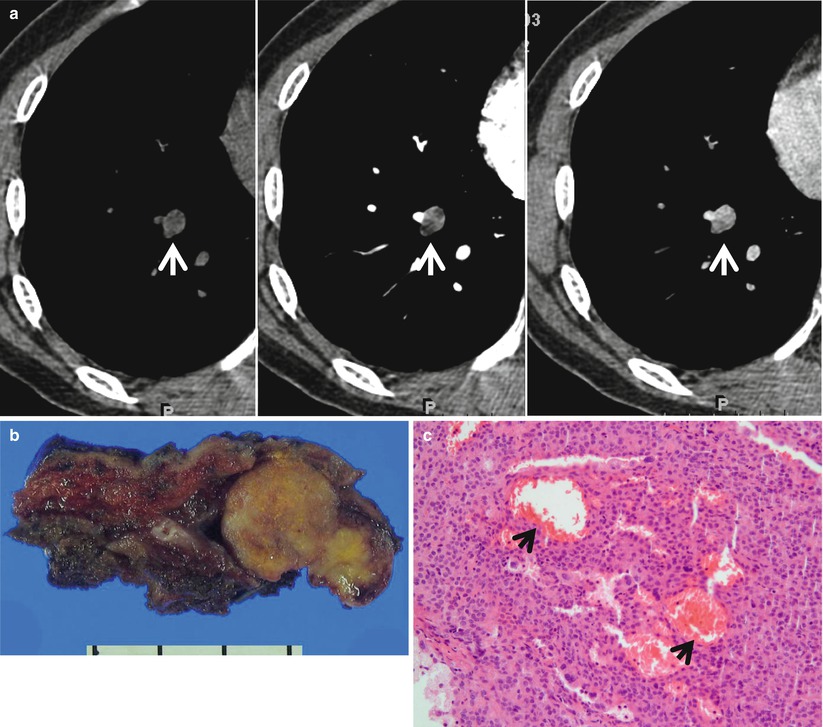

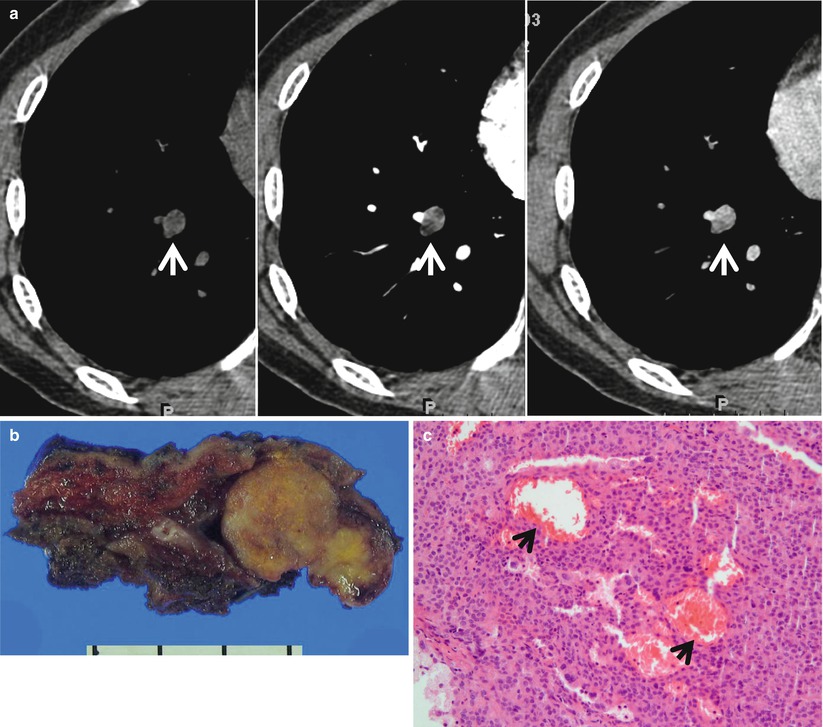

Fig. 1.8

Sclerosing pneumocytoma (hemangiomas) showing high and early enhancement in a 50-year-old woman. (a) Dynamic CT scans obtained at level of suprahepatic inferior vena cava (IVC) show a 16-mm-sized well-defined nodule (arrows) in the right lower lobe. Nodule depicts high enhancement (19 HU, 38 HU, and 69 HU; before, at 1 min, and at 2 min after contrast-medium injection, respectively). (b) Gross pathologic specimen obtained with wedge tumor resection demonstrates a well-defined yellowish round nodule. (c) High-magnification (×200) photomicrograph discloses solid growth of polygonal cells with internal hemorrhagic spaces (arrows)

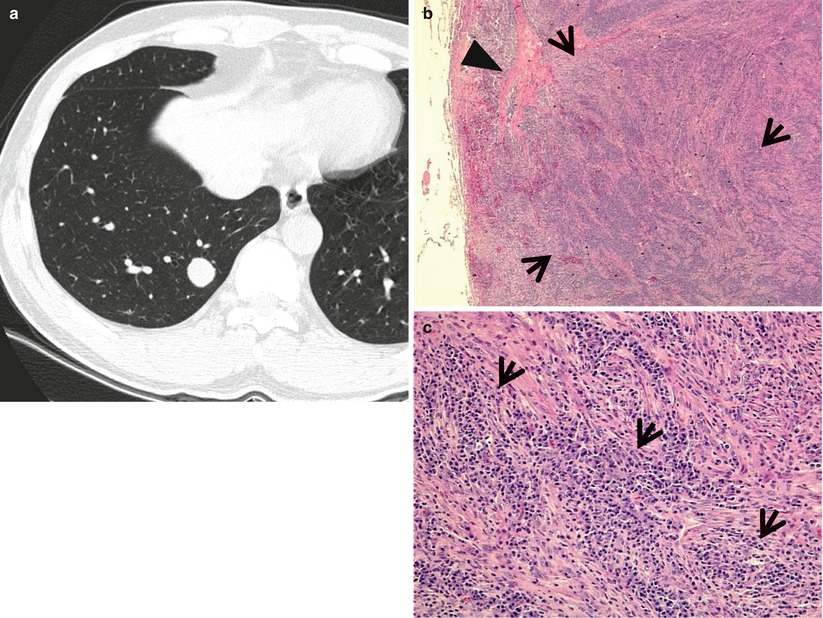

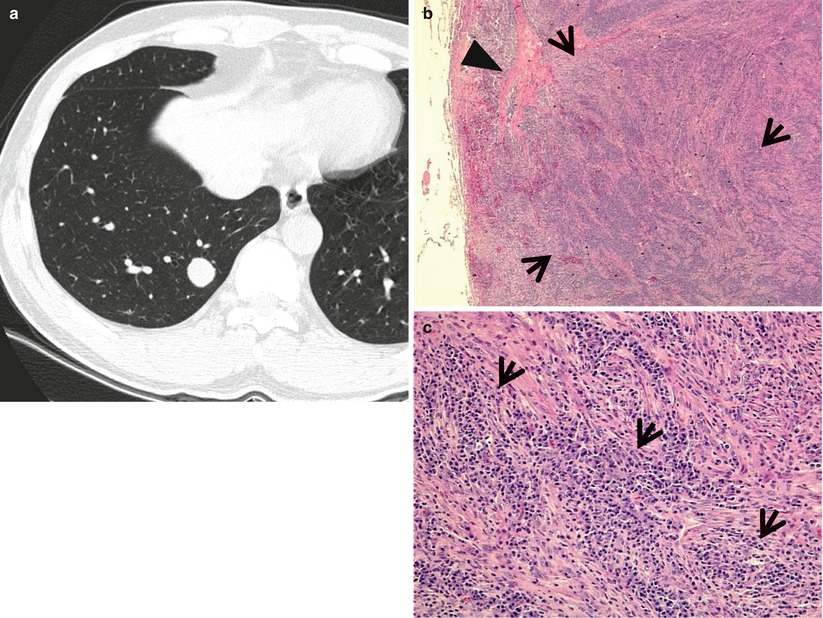

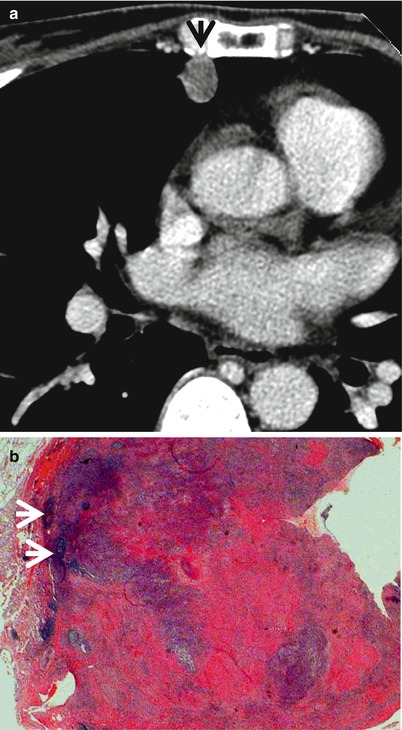

Fig. 1.9

Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor in a 29-year-old man. (a) Thin-section (2.5-mm section thickness) CT scan obtained at level of suprahepatic inferior vena cava (IVC) shows a 19-mm-sized well-defined nodule in the right lower lobe. (b) Low-magnification (×2) photomicrograph of wedge resection of tumor from the right lower lobe demonstrates areas of inflammatory cell infiltration (arrows; mainly composed of plasma cells) and fibrosis (arrowhead). (c) High-magnification (×100) photomicrograph discloses fascicular spindle cell proliferation and admixed areas of lymphocytes and plasma cells (arrows)

Fig. 1.10

ANCA (antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody)-associated granulomatous vasculitis (former Wegener’s granulomatosis) manifesting as a solitary pulmonary nodule in a 51-year-old woman. (a) Mediastinal window image of CT scan (5.0-mm section thickness) obtained at level of the right middle lobar bronchus shows a 13-mm-sized nodule (arrow) in the right middle lobe. (b) Low-magnification (×40) photomicrograph of wedge resection of tumor from the right middle lobe demonstrates basophilic inflammatory nodule containing geographic necrotic areas (arrows)

Table 1.1

Common diseases manifesting as solitary pulmonary nodule

Disease | Key points for differential diagnosis |

|---|---|

Malignant nodule | |

Lung cancer | Wash-in values of >25 HU, lobulated or spiculated margin, and absence of a satellite nodule |

Carcinoid | Lobulated nodule with dense enhancement |

BALT lymphoma | Consolidation or nodules with air bronchograms |

Solitary metastasis | |

Benign nodule | |

Granuloma | No or little enhancement, satellite nodules |

Hamartoma | Focal areas of fat or calcification, septal or cleft-like enhancement |

Sclerosing hemangioma | Subpleural homogeneous mass, rapid and strong enhancement |

Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor | |

Rheumatoid nodule | |

Parasitic infection (PW) | Cavitary nodules or masses in the subpleural or subfissural areas |

ANCA-associated granulomatous vasculitis | Multiple, bilateral, subpleural nodules or masses |

Distribution

Likelihood ratio for malignancy in upper and middle lobe nodule is 1.22 as compared with 0.66 in lower lobe nodule [3].

Clinical Considerations

The hierarchy of radiologic and clinical likelihood ratios for malignancy includes, in decreasing rank, a cavity of 16 mm in thickness, irregular or speculated margin on CT scans, patient complaints of hemoptysis, a patient history of malignancy, patient age >70 years, nodule size of 21–30 mm in diameter, nodule growth rate of 7–464 days, an ill-defined nodule on chest radiographs, a currently smoking patient, and nodules with indeterminate calcification on CT scans [3].

Key Points for Differential Diagnosis

1.

2.

On multivariate analysis, lobulated or spiculated margin and the absence of a satellite nodule appear to be independently associated with malignant nodule with high odd ratio [7].

3.

Diffuse, laminated, central nodular, and popcorn-like calcifications within nodules suggest benignity; on the other hand, eccentric or stippled calcifications have been described in malignant nodules [1].

5.

Evaluation based on analyses of wash-in values (>25 HU) plus morphologic features (lobulated or spiculated margin and absence of a satellite nodule) on dynamic CT appears to be the most efficient method for characterizing an SPN [9].

6.

By rendering both morphologic and metabolic information, 18fluorine fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET–CT allows significantly better specificity than CT alone or PET alone, and both PET–CT and PET alone provide more confidence than CT alone for the characterization of SPNs [10]. But due to expensive cost and high radiation dose, it may be selectively used to characterize SPNs when dynamic CT shows inconsistent results between morphologic and hemodynamic nodule characteristics [1].

7.

Specifically for small nodules less than 10 mm in diameter, serial volume measurements of nodules are regarded as the most reliable technique for their characterization [1].

Lung Cancer (Solid Adenocarcinoma)

Pathology and Pathogenesis

Adenocarcinoma is the most common histologic type of lung cancer in many countries. Adenocarcinoma is a malignant epithelial tumor with glandular differentiation or mucin production, showing lepidic, acinar, papillary, solid, and micropapillary pattern or a mixture of these patterns [11] (Figs. 1.1 and 1.3).

Symptoms and Signs

Patients with lung cancer presenting with an SPN are usually asymptomatic. Physical examination shows no specific abnormality. In most cases, the SPN is detected by routine chest imaging.

CT Findings

The characteristic CT finding of solid adenocarcinoma consists of a solitary nodule or mass with a lobulated or spiculated margin. On multivariate analysis, lobulated or spiculated margin and the absence of a satellite nodule appear to be independently associated with malignant nodule with high odd ratio [7]. The nodules enhance following intravenous administration of contrast medium. The enhancement of >25 HU plus morphologic malignant features on dynamic CT appears to be the most efficient method for characterizing a malignant SPN [9].

CT–Pathology Comparisons

The histopathologic correlation of spiculated margin is variable and may correspond to the strands of fibrous tissue that extend from the tumor margin into the lung, to the direct infiltration of tumor into the adjacent parenchyma, to the small foci of parenchymal collapse as a result of bronchiolar obstruction by the expanding tumor, or to the spread of tumor cells into the lymphatic channels and interstitial tissue of adjacent vessels, airways, or the interlobular septa [12]. The enhancement of nodules presumably reflects the vascular stroma of the tumor [13].

Patient Prognosis

In solitary adenocarcinomas with part-solid and solid nodule, the prognosis depends on nodal and distant metastasis. Solid tumors exhibit more malignant behavior and have a poorer prognosis than part-solid tumors [14].

Carcinoid or Atypical Carcinoid

Pathology and Pathogenesis

Carcinoids are slow-growing neuroendocrine tumors characterized by their growth patterns (organoid, trabecular, insular, palisading, ribbon, rosette-like arrangements). They consist of typical carcinoids and atypical carcinoids according to mitotic count or presence of necrosis. Carcinoid is a distinct disease entity, discriminated from other pulmonary neuroendocrine tumors such as large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma or small cell carcinoma [15] (Fig. 1.4).

Symptoms and Signs

Typical carcinoid may be accompanied with hormone-related manifestations. Fewer than 5 % have the carcinoid syndrome (cutaneous flushing, bronchospasm, diarrhea). Cushing’s syndrome can also occur. Atypical carcinoid, one on the contrary, may cause lymph node and distant metastasis in half of the cases.

CT Findings

The most common imaging finding of carcinoid is a lung nodule or a mass. The CT features of a peripheral carcinoid presenting as SPN include a lobulated nodule of high attenuation on contrast-enhanced CT; nodule that densely enhances with IV contrast-medium administration; the presence of calcification (approximately 30 % of cases have calcification on CT) (Fig. 1.4); subsegmental airway involvement on thin-section analysis; and nodules associated with distal hyperlucency, bronchiectasis, or atelectasis [16]. Typical carcinoid tends to be smaller (average diameter 2 cm) than atypical carcinoid (average diameter 4 cm) [17]. Secondary effects on distal lung parenchyma such as distal hyperlucency are uncommon in atypical carcinoids.

CT–Pathology Comparisons

The neoplastic cells of carcinoids are grouped in small nests or trabeculae separated by a prominent vascular stroma (Fig. 1.4). Because of their vascular stroma, most carcinoids show marked enhancement following intravenous administration of contrast [18]. Segmental or lobar atelectasis, obstructive pneumonitis, and segmental oligemia are related to complete or partial obstruction of airway.

Patient Prognosis

Since typical carcinoids are extremely slow growing, the long-term prognosis is excellent if completely resected. However, all carcinoids are malignant although indolent. Nodal involvement clearly affects survival [19]. The 5-year survival of patients with atypical carcinoids is only 57 %.

BALT Lymphoma

Pathology and Pathogenesis

Pulmonary marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue (BALT) is an extranodal lymphoma, which is thought to arise in acquired MALT secondary to inflammatory or autoimmune processes. The neoplastic cells infiltrate the bronchiolar epithelium, forming lymphoepithelial lesion [20] (Fig. 1.5).

Symptoms and Signs

BALT lymphoma of SPN rarely causes pulmonary symptoms. Weight loss and night sweating may be found. Extrapulmonary symptoms and signs of connective tissue diseases such as Sjögren’s syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus, and rheumatoid arthritis may occur.

CT Findings

Typical CT findings of BALT lymphoma include solitary (Fig. 1.5) or multifocal nodules or masses and areas of airspace consolidation with an air bronchogram [20, 21]. Less common findings include ground-glass opacity (GGO) lesion, interlobular septal thickening, centrilobular nodules, and bronchial wall thickening and pleural effusion.

CT–Pathology Comparisons

CT findings of BALT lymphoma showing solitary or multifocal nodules or masses and areas of airspace consolidation are related to proliferation of tumor cells within the interstitium such that the alveolar airspaces and transitional airways are obliterated [22] (Fig. 1.5). Because the bronchi and membranous bronchioles tend to be unaffected, an air bronchogram is common. Interlobular septal thickening, centrilobular nodules, and bronchial wall thickening on CT images are related to perilymphatic interstitial infiltration of tumor cells.

Patient Prognosis

BALT lymphoma shows the indolent clinical course. The estimated 5- and 10-year overall survival rates have been reported to be 90 and 72 %, respectively [23]. Age and performance status are the prognostic factors.

Tuberculoma

Pathology and Pathogenesis

Tuberculoma is a parenchymal nodular histologic reaction which is primarily granulomatous and necrotizing with frequent cavitation. The granulomas may have palisading histiocytes, prominent epithelioid cells, or Langerhans-type giant cells. These necrotizing granulomas can progress to fibrosis and calcification [24] (Fig. 1.6).

Symptoms and Signs

In active tuberculoma, constitutional symptoms (fever, malaise, night sweating, weight loss, and anorexia) as well as respiratory symptoms (cough, blood-tinged sputum) occur infrequently. Most patients with inactive tuberculoma are asymptomatic.

CT Findings

Tuberculoma is seen as a sharply marginated round or oval lesion measuring 0.5–4.0 cm in diameter [10, 25]. However, fibrosis related to vessels, interlobular septa, or lung parenchyma adjacent to the nodule may result in a spiculated margin. Calcification within the nodule is present in 20–30 % of cases. Satellite nodules around the tuberculoma may present in as many as 80 % of cases [26]. Following intravenous administration of contrast medium, tuberculomas usually show no or little enhancement although sometimes show ringlike enhancement [27] (Fig. 1.6).

CT–Pathology Comparisons

The central part of tuberculoma consists of caseous material and the periphery of epithelioid histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells and a variable amount of collagen. Ringlike enhancement corresponds histologically to the granulomatous inflammatory tissue capsule, whereas the non-enhancing area corresponds to the central necrotic material [27].

Patient Prognosis

It has been reported that a majority of pulmonary tuberculomas show decrease in size with antituberculous treatment. Over 15 % did not show a decrease in size even after the medical treatment [28].

Hamartoma

Pathology and Pathogenesis

Symptoms and Signs

Pulmonary hamartomas are usually asymptomatic and found incidentally when imaging the chest for other reasons. It can occasionally present with hemoptysis, bronchial obstruction, and cough (especially endobronchial types) [30].

CT Findings

The characteristic CT findings of hamartomas are comprised of a lesion of 2.5 cm or smaller in diameter, of a smooth margin, and of focal areas of fat (CT attenuation values between −40 and −120 HU) or calcification [8]. However, these findings are present in only 30–50 % of the tumors (Fig. 1.7). Recent MRI and dynamic CT studies demonstrate septal or cleft-like enhancements of pulmonary hamartomas [31, 32].

CT–Pathology Comparisons

Hamartomas are composed of mature cartilage and fat, which are often surrounded by a thin layer of loose mesenchymal tissue. Recent MRI and dynamic CT studies demonstrated septal or cleft-like enhancement of pulmonary hamartomas [31, 32]. Pathologically, these structures were found to represent variable mesenchymal tissue components arrayed along respiratory epithelial cells lining the cleft and show richer vascularity than main cartilaginous portion of pulmonary hamartoma.

Patient Prognosis

Surgical resection is curative. Recurrence or malignant transformation is rare.

Sclerosing Hemangioma

Pathology and Pathogenesis

Symptoms and Signs

Most patients are asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis.

CT Findings

On CT scans, SH appears as a well-defined, round- or oval-shaped, homogeneous mass with smooth margin in subpleural area [34]. On dynamic CT, it has strong and rapid enhancement [35] (Fig. 1.8). Unusual manifestations of SH include mediastinal mass, tumor with a cystic appearance, air trapping around the tumor, multiple tumors, or a tumor surrounded by multiple daughter nodules in the same lobe; it can also be accompanied by hilar lymph node metastasis [36–40].

CT–Pathology Comparisons

Patient Prognosis

Regardless of surgical resection, the prognosis of patients with sclerosing hemangioma is excellent in cases manifesting as SPN.

Inflammatory Myofibroblastic Tumor

Pathology and Pathogenesis

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree