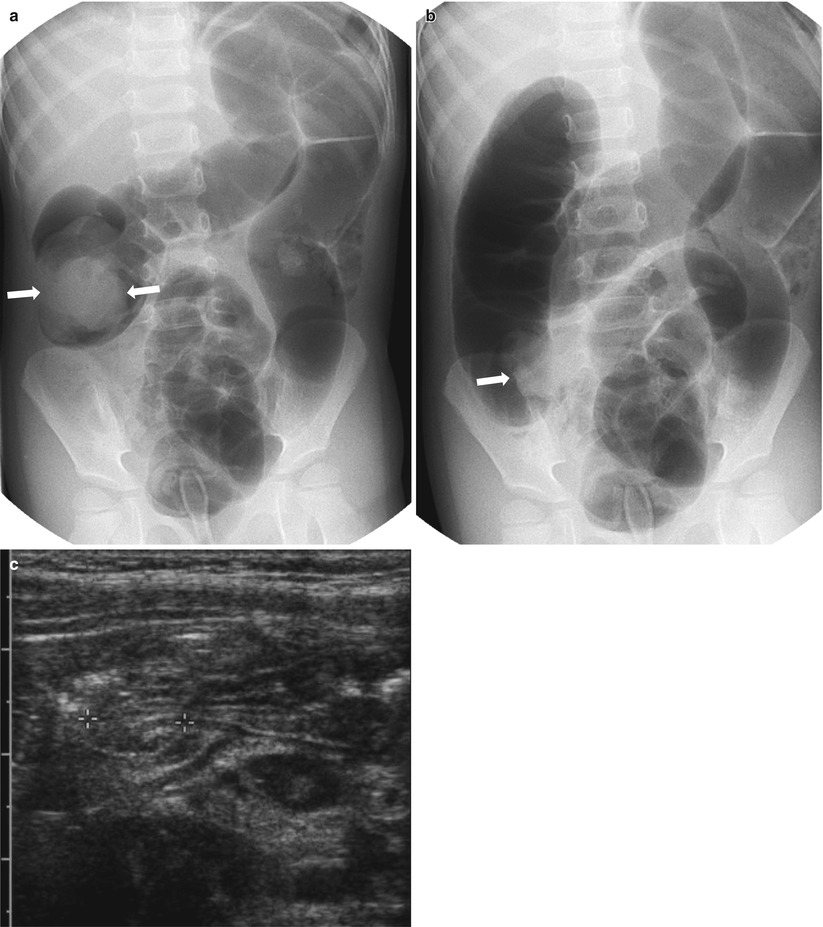

Fig. 20.1

Hypertrophic pyloric stenosis in an 8-week-old infant with vomiting. (a) Supine abdominal radiograph shows gaseous distension of the stomach with prominent peristaltic waves (arrows), called “caterpillar sign.” There is a paucity of distal bowel gas. (b, c) US images in longitudinal and transverse scan of the pylorus demonstrate thickened elongation of the hypoechoic pyloric muscle (arrows) measured 5 mm in thickness (cursor #1) and 22 mm in length (cursor #2). Transverse scan shows a typical donut appearance of the thickened pylorus (arrows) with central increased echogenicity (asterisk) representing a crowded mucosa

Fig. 20.2

Hypertrophic pyloric stenosis: US with fluid filling of the stomach. Longitudinal image of the pylorus after filling the stomach with fluid (asterisk) demonstrates fixed elongation of the pyloric canal with thickening of the muscle. Note shouldering (arrow) of the thickened pylorus and protrusion of the echogenic mucosa into the fluid-filled antrum

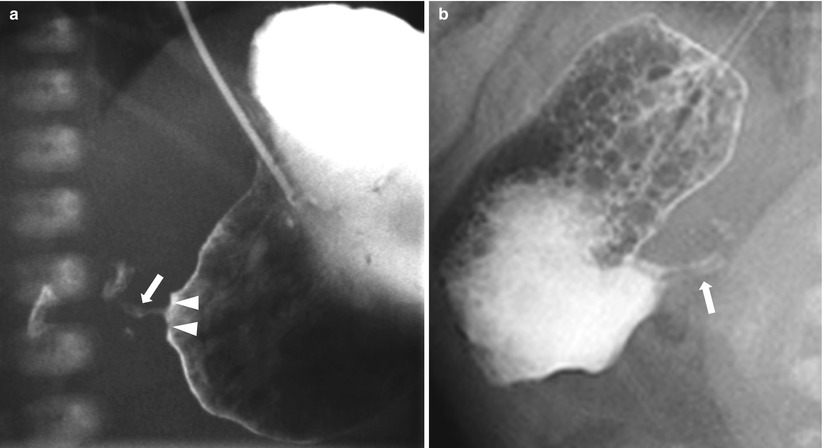

Fig. 20.3

Hypertrophic pyloric stenosis: barium study. (a) Upper GI series shows the elongated and narrowed pyloric canal (arrows) with impression on the antrum producing the shoulder sign (arrowhead). (b) In another patient, an oblique view of upper GI series shows two parallel streaks (arrows) of contrast within the elongated pylorus, called a “double track” sign, representing trapped fluid between thickened folds of the pylorus

20.4.2 Pyloric Spasm

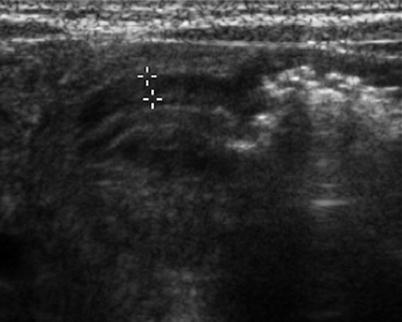

Fig. 20.4

Pyloric spasm in a 3-week-old infant with vomiting. Longitudinal US image of the pylorus shows mild thickening of the pyloric muscle, measured 2 mm in thickness (cursor), which does not meet the criteria for HPS. During the examination, appearance of the pyloric canal changed with the passage of fluid through the pylorus (not seen here)

20.4.3 Necrotizing Enterocolitis

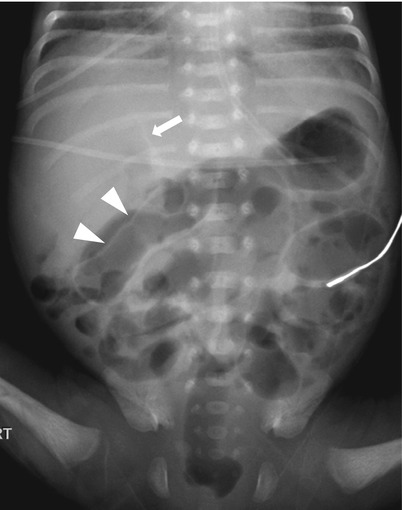

Fig. 20.5

Portal vein gas and pneumatosis intestinalis in necrotizing enterocolitis. Supine radiograph in a premature baby shows portal vein gases (arrowheads) which appear as branching hyperlucencies within the liver. Extensive pneumatosis intestinalis seen as curvilinear or bubble-like hyperlucencies along the bowel loops is also noted in both sides of the abdomen as well as generalized distension of the bowels

Fig. 20.6

Pneumoperitoneum in necrotizing enterocolitis. Supine radiograph in a premature baby demonstrates hyperlucency in upper abdomen with visualization of falciform ligament (arrow), indicating presence of intraperitoneal free air. The free air also outlines the outer wall of the bowel (arrowheads), which is called as Rigler sign. There is moderate diffuse enteric distension with gas

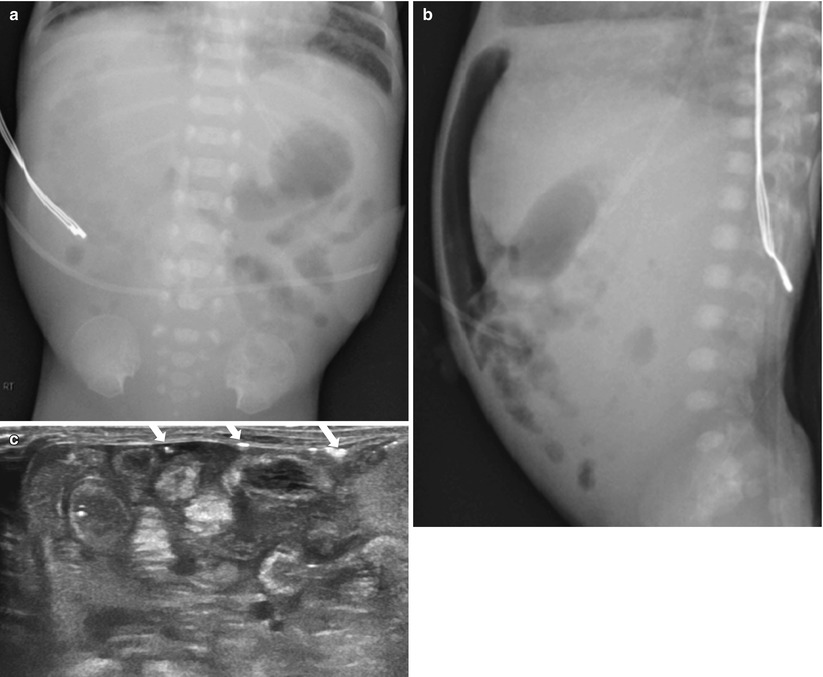

Fig. 20.7

Advanced necrotizing enterocolitis. (a) Supine radiograph shows abdominal distension and markedly asymmetric bowel gas pattern with paucity of bowel gas in right side. Hyperlucent area is noted in right upper quadrant, representing pneumoperitoneum. (b) Cross-table lateral view confirms presence of intraperitoneal free air anteriorly. (c) US demonstrates echogenic bowel walls with complicated ascites. Free gases are seen as multifocal hyperechoic speckles (arrows) within the peritoneal fluid and beneath the abdominal walls. On surgery, necrosis with multiple perforations of the ileum was confirmed

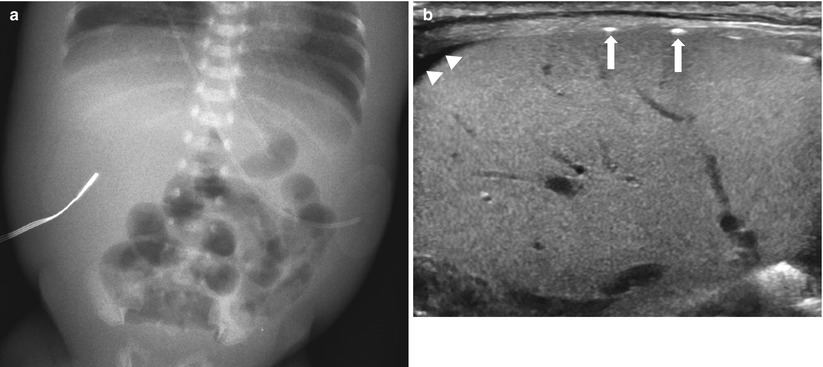

Fig. 20.8

Advanced necrotizing enterocolitis. (a) Supine radiograph in a premature baby shows gaseous dilatation of the bowel loops and marked thickening of the abdominal wall, probably due to edema. Free air is not definitely noted. (b) US demonstrates multifocal hyperechogenecity (arrows) along the surface of the liver, representing free gas. Note free peritoneal fluid (arrowheads). Surgery confirmed perforation of terminal ileum

20.4.4 Intussusception

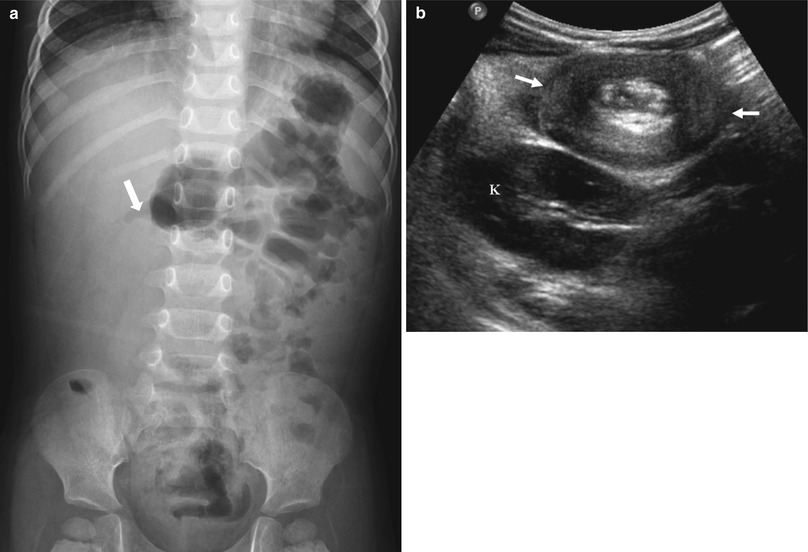

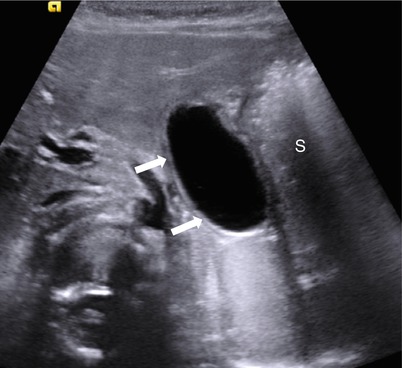

Fig. 20.9

Ileocolic intussusception in a 15-month-old boy presented with abdominal pain and bloody stool. (a) Abdominal radiograph shows a soft-tissue mass-like opacity (arrows) with relative paucity of bowel gas in right abdomen. (b) US of right abdomen shows the typical appearance of intussusception (arrows), similar to the adjacent kidney (K), referred to as the “pseudokidney” sign

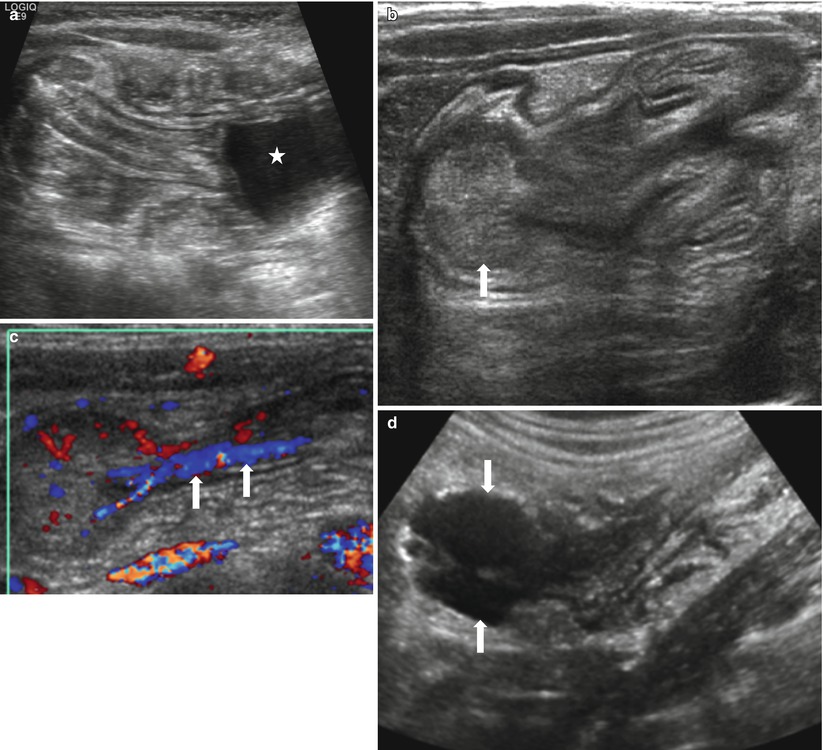

Fig. 20.10

Three different cases of intussusception with pathologic lead points. (a) US in a 7-month-old girl presented with cyclic irritability shows an intussusception (arrows) in a longitudinal axis. A cystic lesion (asterisk) with inner echogenic and outer hypoechoic wall is present as a lead point, which turned out to be a duplication cyst. (b, c) US images in a 4-year-old girl who had multiple episodes of intussusception demonstrate a polypoid lesion within the bowel leading to a short segmental ileocolic intussusception. On color Doppler image (c), prominent vascular flow is noted in the polyp and the stalk (arrows). Colonoscopic examination revealed a polyp in the cecum. Juvenile retention polyp was confirmed by polypectomy. (d, e) US (d) and coronal contrast-enhanced CT (e) images in a 12-year-old boy presented with recurrent abdominal pain show a homogenous solid mass (arrows) with lobulating contour leading to ileocolic intussusception. Note marked hypoechogenicity of the mass simulating cystic lesion on US. Ileocecal resection was performed and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of terminal ileum was finally proved

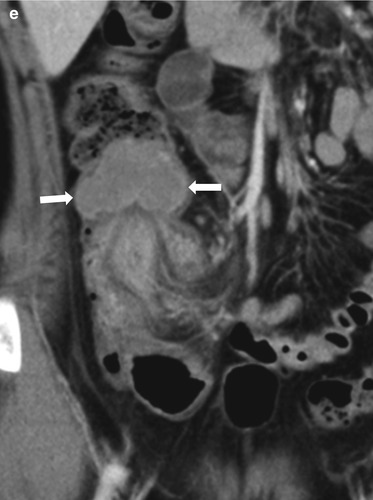

Fig. 20.11

Intussusception in a 17-month-old boy presented with a 3-day history of decreased activity. (a) Upright abdominal radiograph reveals marked distension of small-bowel loops with multiple air-fluid levels suggesting mechanical ileus. Pneumoperitoneum is not seen. (b) CT demonstrates an intussusception (arrows) in which the invaginated multilayered bowels show somewhat decreased enhancement of walls with entrapped fluid. Air reduction was failed and an ileoileocolic-type intussusception was confirmed, followed by surgical resection of ileoileal component due to failure of manual reduction

Fig. 20.12

Air reduction of intussusception: a potential pitfall. (a) Spot image taken during air reduction demonstrates an intraluminal soft tissue mass (arrows) in the hepatic flexure compatible with the intussusceptum. (b) Postreduction image reveals a persistent mass-like opacity (arrows) on the medial aspect of the cecum, in the expected region of the ileocecal valve. This may represent an edematous ileocecal valve, a remnant intussusceptum, or a pathologic leading point. (c) Following US shortly after air reduction confirms an edematous ileocecal valve (calipers) without evidence of remnant intussusception

20.4.5 Duplication Cyst

Fig. 20.13

Gastric duplication cyst in a 6-month-old infant. Transverse US image of upper mid-abdomen shows a typical duplication cyst (arrows) with “double wall” sign along the lesser curvature side of the stomach (S)

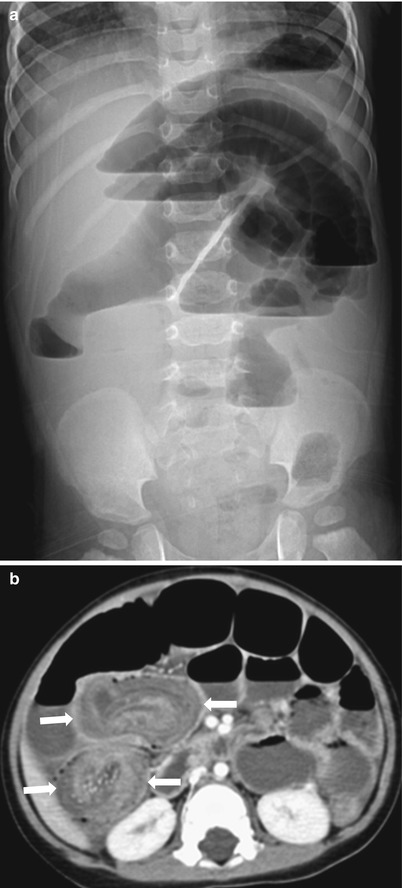

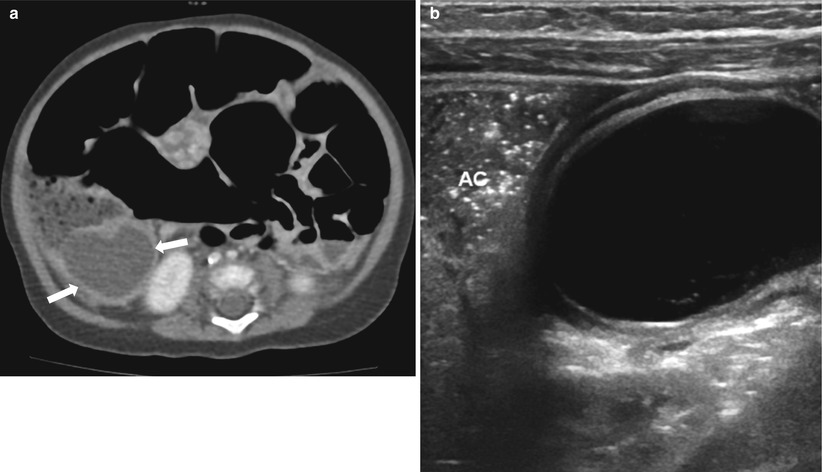

Fig. 20.14

Duplication cyst of terminal ileum presented with abdominal distension and vomiting in a 3-month-old infant. (a) Abdomen CT demonstrates diffuse gaseous dilatation of the bowel loops and a cystic mass (arrows) abutting right colon filled with feces. (b) On US, the inner hyperechoic and outer hypoechoic wall of the cyst is well demonstrated in keeping with duplication cyst. At surgery, the duplication cyst turned out to be originating from the terminal ileum. AC ascending colon

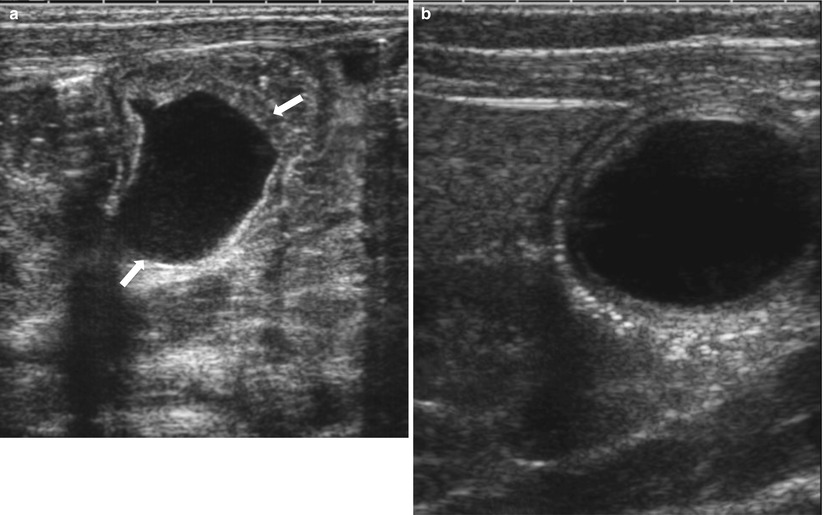

Fig. 20.15

Prenatally detected duplication cyst in a female newborn. Postnatal initial (a) and 2-month follow-up (b) US images show a duplication cyst (arrows) that slightly changes in its shape. Peristalsis of the cyst was visible on real-time US. Note that the “double wall” sign is more clearly visualized on the latter US performed with a higher-frequency transducer. Prenatally, it had been suspected to be an ovarian cyst

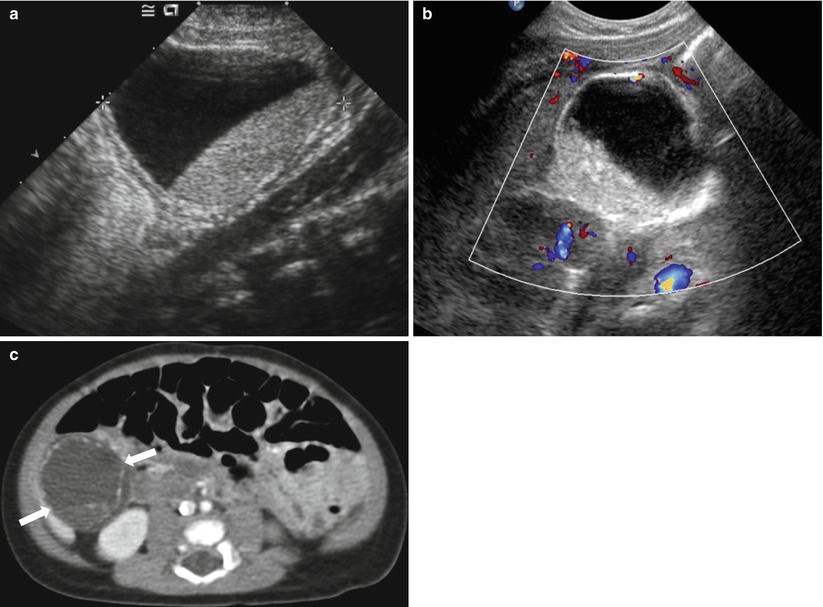

Fig. 20.16

Complicated neonatal ovarian cyst simulating a duplication cyst in a female newborn. Grayscale (a) and color Doppler (b) US images of right abdomen show a large unilocular cystic mass with internal fluid-fluid level. The wall of the cyst appears to be echogenic in inner layer and hypoechoic in outer layer, similar to that of a duplication cyst. On CT (c), multifocal linear calcifications along the periphery of the cyst are seen, resulting in a sonographic echogenic wall. Torsion of ovarian cyst with autoamputation was surgically confirmed in this patient

20.4.6 Meckel’s Diverticulum

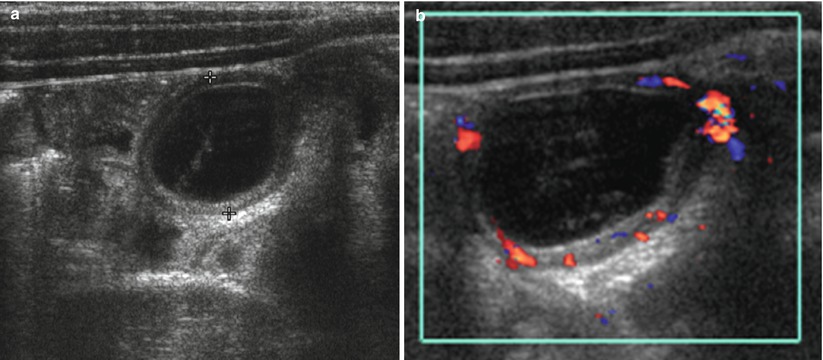

Fig. 20.17

Meckel’s diverticulum in a 7-year-old boy presented with right lower quadrant pain. (a) Transverse US of right abdomen shows a cystic lesion (calipers) with gut signature (hyperechoic inner wall and hypoechoic outer wall). Compared with adjacent bowels that are collapsed, it revealed loss of compressibility in real time. (b) Color Doppler study shows increased vascularity within the wall of the cyst, suggesting presence of inflammation. Appendix was not remarkable in this patient

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree