Fig. 6.1

Long-standing rheumatoid arthritis in an elderly patient, showing generalized osteoporosis, narrowing of the wrist and carpal joint spaces, and erosions and luxation of the metacarpophalangeal joints

However, if radiographic bone erosions are highly specific for the diagnosis of RA, the sensitivity of their depiction is only fair at the early stage of the disease (Østergaard et al. 2008; Backhaus et al. 2002). Better accuracy in the detection of bone erosions using tomosynthesis has been reported, but further studies are needed to confirm these results (Canella et al. 2011). Computed tomography (CT) is infrequently used for this indication, since it is mainly performed for the assessment of bone destruction and stability in a preoperative setting (Sommer et al. 2005). Ultrasonography (US) and MR imaging can best depict synovitis and tenosynovitis and may show erosions at a stage where conventional radiographies are still normal (Figs. 6.2 and 6.3) (Olivieri et al. 2009; Backhaus et al. 2002; Boutry et al. 2003).

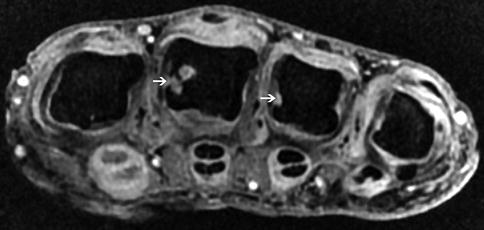

Fig. 6.2

Axial fat-saturated T1-weighted image of the hand after gadolinium administration, depicting synovitis of the MCP joints, marginal erosions (arrows) of the radial aspects of the third and fourth metacarpal heads, and tenosynovitis of the flexor tendons

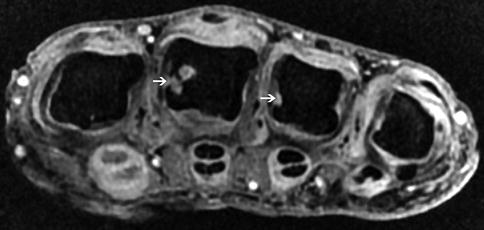

Fig. 6.3

Longitudinal US image of the second MCP joint, showing effusion and marginal erosions (arrows) of the radial aspect of the metacarpal head in a RA patient

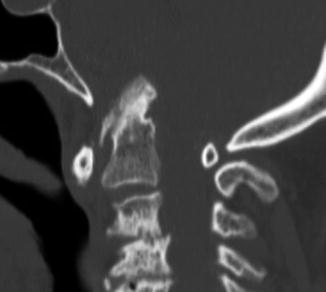

In the elderly group, two other important considerations are bone loss and involvement of the cervical spine. It has been shown that increased RA activity and severity are associated with accelerated bone loss, which can be as high as 1 % per year (Pye et al. 2010). This finding can be aggravated by factors such as inactivity and corticoid therapy, which can increase the risk of fracture (Resnick and Cone 1984; van Staa et al. 2006; Kim et al. 2010). The rate ratios for the occurrence of osteoporotic fractures among RA patients are 1.35 (>85 years), 1.54 (75–84 years), and 2.13 (65–74 years) compared with non-RA subjects (Kim et al. 2010). Cervical spine abnormalities in RA show a positive correlation with age and with the duration of disease (Wolfe et al. 1987). Erosions, chondrolysis, and subluxations may involve the upper (C0–C1 and C1–C2 joints) and lower cervical joints, with potential subsequent compression of the spinal cord (Fig. 6.4) (Kroft et al. 2004). This complication is especially significant in patients with a superimposed degenerative spinal disease (e.g., discopathy and ligamentum flavum hypertrophy).

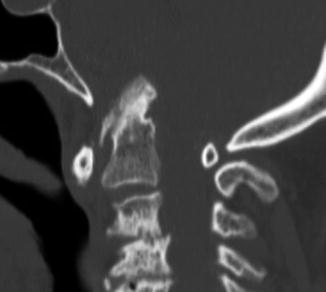

Fig. 6.4

Sagittal CT reformation showing a basilar invagination and erosions of the odontoid process in a 78-year-old man with RA. Multilevel disk space narrowing with erosions and subchondral sclerosis of the vertebral end plates are associated

In the elderly, the list of the differential diagnoses of RA is extensive, since various entities with similar signs and symptoms are prevalent in this population (Kavanaugh 1997). This list includes inflammatory diseases (polymyalgia rheumatica, spondyloarthritis, crystal deposition disease, paraneoplastic arthritis, viral arthritis, etc.), and noninflammatory disorders (osteoarthritis, rotator cuff tendinopathy, frozen shoulder, hypothyroidism, and Parkinson disease) (Olivieri et al. 2009). Some of these conditions, such as gout and osteoarthritis (OA), are far more common than RA, but their clinical presentation in elderly patients may be less typical, sometimes resembling RA (Kavanaugh 1997; Jacobson et al. 2008b). Moreover, it should be noted that patients with chronic and/or treated inflammatory arthritis may develop secondary changes of osteoarthritis (Jacobson et al. 2008b).

A subset of patients with elderly-onset RA may present with polymyalgic symptoms that are sometimes difficult to differentiate from polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR) (Turkcapar et al. 2006; Gonzalez-Gay et al. 2001). Polymyalgia rheumatica and RA may present similarly in the elderly, with involvement of the girdles, severe morning stiffness, raised erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and a good response to prednisone (Caporali et al. 2001). Besides, it is accepted that PMR can occur in patients with well-established classic RA, just as RA can develop in patients who have previously presented with PMR (Gonzalez-Gay et al. 2001; Caporali et al. 2001; Häntzschel et al. 1991). The main imaging features in most PMR patients are widespread bursitis and tenosynovitis, involving mainly the subdeltoid and subacromial bursae, the trochanteric bursae, and the long head of the biceps (Breuer and Nesher 2012). Peripheral synovitis may be present in up to 25 % of patients with PMR and is frequently asymmetric and nonerosive (Gonzalez-Gay et al. 2001).

Another possible differential diagnosis is remitting seronegative symmetrical synovitis with pitting edema syndrome (RS3PE), which is characterized by acute-onset polyarthritis in elderly patients, distal synovitis and tenosynovitis, male predominance, and acute-onset pitting edema of the hands and/or feet (Salam et al. 2008). The remarkable features of this syndrome are seronegativity for RF and an excellent response to low-dose steroids, with long-term remission (Salam et al. 2008).

Some clinical signs of spondyloarthritis involving peripheral joints may pose problems in the differential diagnosis for RA, e.g., psoriatic arthritis without cutaneous lesions (Narváez et al. 2010). Psoriatic arthritis differs from RA in that the occurrence of periarticular osteopenia and erosions is less frequent, as well as by the presence of bony proliferation, osteolysis, bone ankylosis, and enthesitis; the joints affected are not the same (Narváez et al. 2010). Unlike RA, PA usually evidences extensive involvement of the distal interphalangeal joint and asymmetric distribution (Narváez et al. 2010).

Finally, paraneoplastic arthritis should also be taken into consideration when dealing with the elderly. This subset of arthritis usually has an abrupt onset and is often seronegative and asymmetric; it especially affects the lower extremities (Szekanecz et al. 2011). This condition has been associated with breast, colon, lung, ovarian, gastric, and esophageal cancers, as well as lymphoproliferative diseases (Szekanecz et al. 2011). Because autoimmune diseases and malignancies can develop in a short time, it may be difficult to distinguish an autoimmune paraneoplasia appearing in a cancer patient from a secondary tumor occurring in an autoimmune disease (Szekanecz et al. 2011).

6.3 Spondyloarthritis

This heterogeneous group of diseases evidences common features, such as tropism for entheses and involvement of the axial and appendicular skeleton; the differences concern the pattern of radiographic findings and the clinical history (Punzi et al. 1999; López-Montilla et al. 2002; Jacobson et al. 2008a; Sebes et al. 1978; Denis et al. 2010; Miquel et al. 2010). Late-onset spondyloarthritis (>55 years) is very uncommon, and most cases are accounted for by undifferentiated spondyloarthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and psoriatic arthritis (Caplanne et al. 1997; Olivieri et al. 2009).

The clinical and biological presentation of spondyloarthritis in the elderly differs from that seen in younger patients (<40 years) (Caplanne et al. 1997). Upper inflammatory spinal pain (cervical and thoracic), anterior chest wall involvement, peripheral arthritis, and aseptic osteitis are significantly more frequent in older patients (Caplanne et al. 1997). The frequent common genetic antigen, HLA B27, observed in young patients, seems to be less frequent in the late-onset spondyloarthritis group (López-Montilla et al. 2002; Sebes et al. 1978; Feldtkeller et al. 2003).

Spondyloarthritis begins as an inflammatory process of the fibrous and fibrocartilaginous entheses, leading to increased vascularity and cellular infiltration of these structures (Denis et al. 2010; McGonagle et al. 2002). In the early stage, a nonspecific focal inflammatory lesion destroys the mineralized portion of the enthesis and the adjacent bone; the defects are later repaired by direct deposition of woven bone which forms a new enthesis (Barozzi et al. 1998). The repetition of this process results in a poorly defined, enlarging bone proliferation, which can be observed as enthesophytes, hyperostosis, and/or ankylosis (Denis et al. 2010; Barozzi et al. 1998). It should be noted that the initial manifestations can be depicted by US and MR imaging only, while radiographic and CT changes appear later.

6.3.1 Ankylosing Spondylitis

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is the prototype of spondyloarthritis, characterized by spinal inflammation and new bone formation that can affect entheses, sacroiliac joints, zygapophyseal joints, vertebrae, costovertebral joints, sternocostal joints, and peripheral joints (Jacobson et al. 2008a; Braun and van der Heijde 2002). Its prevalence may vary from 0.03 to 0.9 % according to the population and is higher in men (Helmick et al. 2008; Jacobson et al. 2008a).

Onset of AS after 55 years is uncommon, with an incidence of 2.2/100,000 per year, and the frequency of HLA B27 negative patients is higher (Olivieri et al. 2009; Feldtkeller et al. 2003). These patients may have axial symptoms with or without peripheral arthritis, peripheral enthesitis, or dactylitis (Olivieri et al. 2009). It is believed that there are more similarities than differences between the clinical presentations of late-onset and of classical-onset AS (Olivieri et al. 2009). As in younger patients, MR imaging is particularly useful for the depiction of inflammatory changes of the axial skeleton (Figs. 6.5 and 6.6). Ultrasound is also helpful for the assessment of peripheral enthesitis.

Fig. 6.5

Sacroiliitis of the distal part of the left sacroiliac joint in an elderly patient at an early stage of ankylosing spondylitis (coronal T1- (a), STIR- (b), and post-contrast T1-weighted (c) images)

Fig. 6.6

A 60-year-old man with long-standing ankylosing spondylitis (sagittal T1- (a), T2- (b), and T1-weighted images after gadolinium administration (c)), showing chronic and subacute discovertebral inflammatory changes

However, the elderly may present with long-standing AS, and the physician must be aware of some special complications related to this situation. The first is the risk of horizontal fractures of the rigid osteoporotic spine, even after minor trauma (Fig. 6.7) (Barozzi et al. 1998; Campagna et al. 2009; El Maghraoui 2004). Most of these fractures occur in the cervical spine and present a significant risk of initial or secondary neurologic complications (Fig. 6.8) (Westerveld et al. 2009). Due to multilevel bony fusion, long lever arms develop in the spine, on which forces act during trauma (Westerveld et al. 2009). Hyperextension is the most common cause of fracture, often involving the vertebral body, ossified ligaments, and surrounding tissue and leading to instability (Westerveld et al. 2009). In fractures complicating AS, when paravertebral hemorrhages and injuries to the ligamentum flavum or posterior spine are found, a horizontal fracture should be sought (Koivikko and Koskinen 2008). The fracture line may be transdiscal and/or transvertebral, horizontal or oblique (Michel et al. 2007). In MR imaging, narrow-gap fractures present a low signal in both T1- and T2-weighted images, and with increasing width the gaps present a higher signal on T2-weighted images (Koivikko and Koskinen 2008). The bone marrow edema varies greatly, and in most instances, it is relatively subtle and best depicted in STIR sequence (Koivikko and Koskinen 2008). Such fractures can be missed in conventional radiographies, especially in the aged, but are well evidenced by CT and MR imaging (Michel et al. 2007).

Fig. 6.7

Different patients with long-standing ankylosing spondylitis, demonstrating transverse vertebral fracture at the T9–T10 (a) and L4–L5 (b) levels

Fig. 6.8

A 72-year-old man with long-standing ankylosing spondylitis, showing a transverse vertebral fracture at the cervical spine, C6–C7 on sagittal CT (a), and T2-weighted (b) images. The patient had a severe neurological deficit

Another late but uncommon complication of AS is the cauda equina syndrome (Kotil and Yavasca 2007). This disorder has several possible mechanisms, including fibrosis following arachnoiditis, root damage by dural ectasia and diverticula, and reduced compliance of the caudal sac (Fig. 6.9) (Kotil and Yavasca 2007; Van Hoydonck et al. 2010).

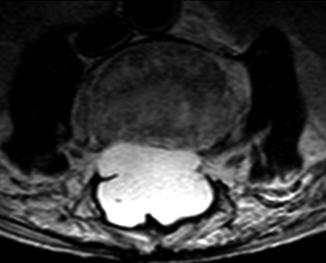

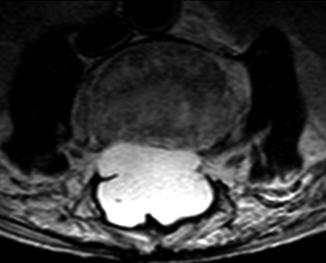

Fig. 6.9

Axial T2-weighted image of the lumbar spine in a patient with long-standing AS, demonstrating dural ectasia

On imaging, the main differential diagnosis of SA in the elderly is represented by diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH) (Olivieri et al. 2007a, 2009). Even though both diseases affect the axial skeleton, extraspinal entheses, and occasionally involve similar kyphotic posture, DISH is a noninflammatory disease in which the spinal longitudinal ligaments and entheses slowly ossify, leading to decreased mobility (Westerveld et al. 2009; Olivieri et al. 2007a). The diagnosis of DISH can be made when ossification of the anterior longitudinal ligament is present on at least four consecutive vertebral bodies, with relative preservation of the intervertebral disk height (Westerveld et al. 2009; Taljanovic et al. 2009). Besides, widespread enthesopathy and arthritis in AS result in intra- and extra-articular fusion of the facet joints, costovertebral joints, and sacroiliac joints, which is not a common feature in DISH (Taljanovic et al. 2009).

6.3.2 Psoriatic Arthritis

Psoriatic arthritis has been defined as a unique form of inflammatory arthritis, usually seronegative, associated with psoriasis (Gladman et al. 2005). This disease affects about 0.15 % of the general population (Helmick et al. 2008; Olivieri et al. 2009; Denis et al. 2010). A majority of patients are adults between 30 and 50 years of age, but in one population study, the disease began after the age of 55 in about a quarter of the PA patients (Helmick et al. 2008; Olivieri et al. 2009; Denis et al. 2010; Kaipiainen-Seppänen 1996). The adult sex ratio is close to 1, but in elderly patients, the male to female ratio is 3:1 (López-Montilla et al. 2002; Denis et al. 2010).

The features that distinguish PA from other forms of spondyloarthritis are association with cutaneous psoriasis (66 % of cases), asymmetric involvement of the skeleton (although symmetric involvement is possible), frequent damage to the distal interphalangeal joints, the inconstant presence of sacroiliitis and the presence of bony erosions with adjacent proliferation (Figs. 6.10 and 6.11), the pencil-and-cup appearance of PIP, DIP, MCP, or MTP joint (s), and the frequent development of intra-articular bony ankylosis, mainly of the interphalangeal joints, rarely of the carpal bones or larger joints (Denis et al. 2010). Destruction of the phalangeal tufts and periostitis can also be seen.

Fig. 6.10

Psoriatic arthritis characterized by diffuse involvement of the MCP, PIP, and DIP joints. Note the ankylosis of most of the interphalangeal joints, the tuft resorption (arrow), and the marginal erosions with bony proliferation of two proximal phalanges (arrowhead)

Fig. 6.11

Calcaneal erosions with adjacent osseous proliferation in a patient with PA. Note the associated bony proliferation of the posterior part of the tibia (arrow)

Elderly people have a significantly higher number of active joints and foot erosions and higher levels of serum C-reactive protein and synovial IL1β and IL6 than younger patients (Olivieri et al. 2009). Besides, late-onset PA is characterized by a more severe acute onset and more severe outcome (Punzi et al. 1999; Olivieri et al. 2009).

The progression of joint damage in PA is highly variable between subjects, and factors such as the presence of tender and/or swollen joints, raised erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and preexisting joint damage at the time of referral to the clinic predict future progression of joint damage (Coates et al. 2010). About 20 % of the patients develop a very destructive disabling arthritis (Gladman et al. 2005).

6.3.3 Undifferentiated Spondyloarthritis

The term “undifferentiated spondyloarthritis” refers to a condition involving inflammatory backache, oligoarticular asymmetric arthritis, and enthesitis, but not fulfilling the diagnostic criteria for any of the currently established forms of spondyloarthritis (Olivieri et al. 2007b, 2009; Aggarwal et al. 1997). Patients may also test positive for B27 and present pitting edema, marked constitutional symptoms, and elevated ESR (Olivieri et al. 2009). Some authors believe that late-onset undifferentiated spondyloarthritis is more common than late-onset ankylosing spondylitis (Olivieri et al. 2009).

6.4 Gout

Gout is a systemic metabolic disease which is considered to be the most common form of inflammatory arthritis in the elderly, affecting up to 8 % of men and 3 % of women over 65 (Schlesinger 2005; Bhansing et al. 2010). This disease is characterized by the formation and reversible deposition of monosodium urate crystals in joints and extra-articular tissues, usually occurring after a prolonged period of hyperuricemia (De Leonardis et al. 2007). The radiological changes can be classified as early, intermediate, and late (Bloch et al. 1980

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree