Introduction

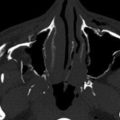

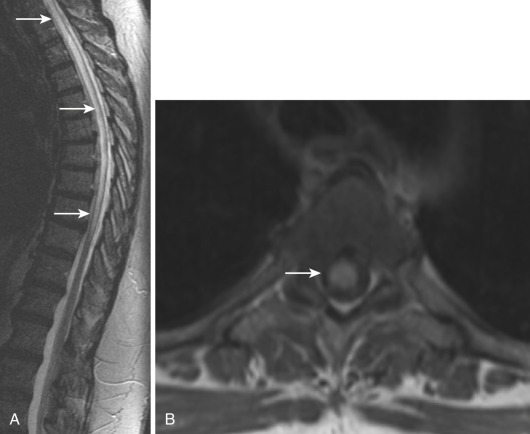

Most noninfectious inflammatory diseases of the spinal cord are autoimmune in nature. Although the number of autoimmune diseases affecting the spinal cord is large, their clinical imaging manifestations are limited, and with few exceptions the most common presentation is transverse myelitis (TM). The typical magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) features of TM ( Fig. 27-1 ) are abnormal high signal on T2-weighted images, often accompanied by contrast enhancement (35%-75%) on postgadolinium T1-weighted images and swelling/expansion (50%) of the spinal cord. Contrast enhancement may be diffuse, poorly defined, and heterogeneous, nodular, or peripheral. TM usually extends over one to four vertebral segments and more often affects the thoracic region. Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) is more sensitive in outlining the true extent of TM than T2-weighted images and has better clinical correlation with the affected levels and severity of symptoms. DTI yields information about axonal fiber tract integrity, and loss of that integrity shows a low fractional anisotropy (FA). DTI shows decreased FA within and distal to the area of TM.

In autoimmune disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), mixed connective tissue disease, scleroderma, Sjögren’s syndrome, multiple sclerosis (MS), acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM), neuromyelitis optica (NMO), and antiphospholipid syndrome, TM is the most common clinical spinal cord manifestation. In this chapter we review the most salient clinical and imaging aspects of the noninfectious inflammatory disorders in which the spinal cord may be involved.

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

SLE most commonly affects African American and Asian females between the ages of 10 and 50 years. Although in most patients SLE is considered to be idiopathic, it may be caused by medications, the most common being isoniazid, hydralazine, and procainamide. TM is a rare complication in SLE, affecting mostly young patients and occurring in the early stage of the disease. MRI findings are variable, and 16% to 30% of patients with clinical myelitis have a normal MRI study. Of the remainder, most have a long region of central cord hyperintensity on T2-weighted images, with expansion and contrast enhancement of the regions. A small percentage of patients have small multifocal bright lesions on T2-weighted imaging.

Longitudinal myelitis is a variant of acute TM in which the cord abnormality on MRI is continuous over more than four vertebral segments. There is abnormal high T2 intramedullary signal intensity accompanied by swelling of the entire transverse section of the spinal cord and often with contrast enhancement. Longitudinal myelitis is a rare but severe complication of SLE and tends to occur in the early phase of the disease in young SLE patients. Early diagnosis and treatment with prednisone and cyclophosphamide may ameliorate its poor prognosis.

Sarcoidosis

Sarcoidosis is a systemic granulomatous disease of unknown etiology that involves multiple organs and is characterized microscopically by the presence of noncaseating granulomas. It is estimated that up to 4 to 20 out of 10,000 people in the United States have sarcoidosis. Overall, central nervous system involvement is diagnosed in 10% to 15% of patients with systemic sarcoidosis. Involvement of the spinal cord in sarcoidosis is extremely rare, occurring in only 0.34% of patients with systemic disease. Sarcoidosis most often occurs between age 20 and 40, with women affected more than men. The disease is 10 to 17 times more common in African Americans than whites. People of Scandinavian, German, Irish, or Puerto Rican origin are also more prone to the disease. Although isolated central nervous system involvement occurs in fewer than 1% of patients, it is often the cause of presenting symptoms. Spinal disease may involve the nerve roots, intracanalicular extradural space, dura, leptomeninges, parenchyma, and surrounding bony spine (vertebral bodies and disks).

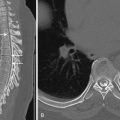

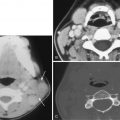

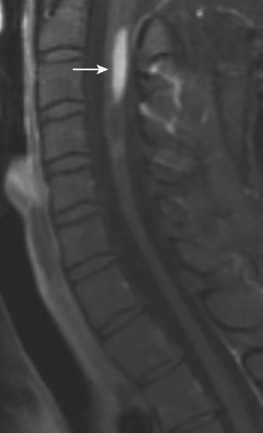

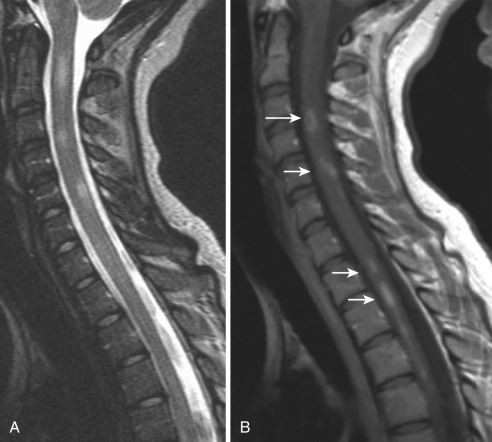

Imaging findings in spinal cord sarcoidosis are nonspecific, and their differential diagnosis includes tumor, MS, and fungal infections. Fusiform enlargement of the cord, with high T2 signal and low T1 signal intensity and patchy contrast enhancement is common ( Fig. 27-2 ). MRI shows abnormal linear and/or nodular contrast enhancement along the surface of the cord. The disease starts at the surface of the cord and then moves into the parenchyma centripetally, presumably via the perivascular spaces. There may also be involvement of the spinal nerve roots that enhance with gadolinium. Spinal cord sarcoidosis occurs at any level as follows: 56% in the cervical region, 37% in the thoracic level, and 7% at the lumbar and sacral levels. With resolution of the inflammatory process, the cord may return to normal size or become atrophic ( Fig. 27-3 ) and show no further contrast enhancement. Spinal cord sarcoidosis is difficult to diagnose because it commonly mimics other diseases, but lesions at more than three distinct levels help distinguish it from TM, which is generally a single lesion. Rapid onset of profound weakness correlates with extensive cord involvement and poor outcome. Rapid resolution of MRI findings following therapy suggests a favorable outcome. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) evaluation usually shows elevated protein and/or pleocytosis. Serum and CSF angiotensin-converting enzyme levels are neither sensitive nor specific for neurosarcoidosis. A confident diagnosis can be made by a positive Kviem test, in which spleen or liver tissues from a patient with known sarcoidosis are intradermally injected, followed by a skin biopsy 4 to 6 weeks later. A positive result will show typical sarcoid granulomata. Biopsy of affected organs may be helpful and can most easily be taken from the skin or the outer membrane of the eyes. Fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography ( FDG-PET) may be useful in evaluating the systemic extent of sarcoidosis, with a sensitivity of 80%, specificity of 67%, and accuracy of 76%. Patients with neurologic sarcoidosis are generally treated with corticosteroids and other immunomodulatory agents.

Multiple Sclerosis

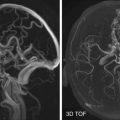

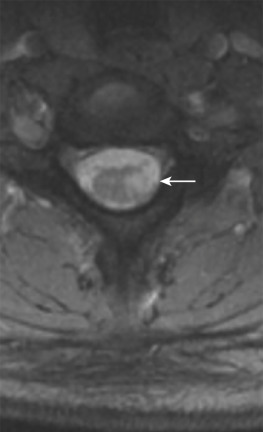

MS is an autoimmune disease in which myelin around axons is destroyed by inflammation. The disorder is most commonly diagnosed between ages 20 and 40 years but may be seen at any age. In the United States approximately 350,000 individuals are affected by MS, and the chance of developing it is 1 : 750. Females are two to three times more likely to develop MS than males, and whites are at a higher risk for it than blacks or Asians. MS may clinically mimic the symptoms of many other disorders; an important component of the diagnosis is oligoclonal bands in CSF. Clinical features of spinal cord involvement include ataxia, weakness (mono/hemi/para/quadriparesis), and paresthesia. On MRI, TM may be a rare initial presentation of MS. Enlargement of the cord is usually seen during the active phase of MS, but this enlargement is subtle and less than expected for the size of the lesions. Spinal cord lesions are cigar shaped and extend less than two vertebral bodies in length. Larger active lesions may have extensive edema with associated cord expansion and may appear as enhancing nodules, rings, or arcs ( Fig. 27-4 ). The period of contrast enhancement may last 2 to 8 weeks. In contrast to TM, these lesions involve less than half of the spinal cord diameter, lie eccentrically, rarely show mass effect, and preferentially affect the lateral cord and posterior columns ( Fig. 27-5 ). The association between spinal cord atrophy and disability progression is strong. Chronic lesions show no contrast enhancement and often result in focal atrophy. DTI is useful in evaluating patients with MS, and cord lesions show low FA and high values of mean diffusivity, implying myelin sheath breakdown and disorganization of the normal directionality of extracellular water movement. Commonly, treatment of cord lesions consists of immunomodulatory therapy with interferon and the monoclonal antibody natalizumab.

Acute Disseminated Encephalomyelitis

ADEM is a severe acute demyelinating disease usually triggered by an inflammatory response to viral or bacterial infections and/or vaccinations. Patients commonly present with nonspecific symptoms including headache, vomiting, drowsiness, fever, and lethargy, all of which are relatively uncommon in MS. The course of ADEM is usually monophasic, and it affects children more commonly than adults, with no predilection for gender. In general, ADEM is self-limited and prognosis is favorable. Although 35% of patients have relapses, complete recovery from ADEM is reported for 57% to 89% of them. One episode of ADEM can be the first manifestation of the classical relapsing form of MS; 21% of patients with ADEM develop MS after 2.36 years and 27% after 5.64 years. Several clinical features help to distinguish between MS and ADEM. In one study the mean age at presentation was 14 years in MS compared with 7 years in ADEM. Encephalopathy and seizures are more common in ADEM, whereas other symptoms such as headache, tremor/dysmetria, ataxia, weakness, and paresthesias are present in both diseases. In ADEM, large active lesions have extensive edema with associated spinal cord expansion and may show enhancing nodules, rings, or arcs ( Fig. 27-6 ). Similar to MS, spinal cord lesions are cigar shaped and extend over less than two vertebral bodies. In contrast to TM, ADEM lesions involve less than 50% of the spinal cord diameter, lie eccentrically, rarely show mass effect, and preferentially affect the lateral cord and posterior columns. First-line treatment for ADEM includes intravenous high-dose corticosteroids, which in nonresponsive patients are followed by plasma exchange or immunoglobulin. Immunosuppressive agents such as mitoxantrone or cyclophosphamide are alternative therapies if antiinflammatory treatment fails.