24

Obstructive Uropathy and Renal Calculus Disease

Ureteral obstruction leads to dilation of the proximal ureter and hydronephrosis. This chapter deals with percutaneous nephrostomy (PCN) and ureteral stenting procedures, which are used to relieve obstruction and help in the management of renal calculus disease.1–3

Clinical Presentation

Clinical Presentation

Many patients presenting with obstructive uropathy have malignancies; the etiology and the obstruction can be bilateral or unilateral. When both kidneys are obstructed, the patient will present in renal failure with elevated blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine levels. This clinical picture often is seen in patients who have prostate cancer, bladder cancer, or gynecologic malignancies. Because malignancies grow slowly, they cause the kidney to dilate slowly. Thus, malignant obstruction is usually painless. Unilateral obstruction caused by malignancy may be difficult to diagnose clinically if the other kidney is functioning normally, because the obstruction is painless and the BUN and creatinine levels may be normal. Unsuspected unilateral obstruction often is detected during the course of an imaging study such as ultrasound or computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen. The decision to treat an asymptomatic unilateral obstruction caused by malignancy is a clinical one that may be influenced by many factors, such as the need to optimize renal function before administration of chemotherapy with known nephrotoxicity (Fig. 24-1).4,5

Patients undergoing PCN for benign causes of obstruction usually have calculi or strictures. Only a small fraction of patients presenting with renal stones require percutaneous decompression. In the acute setting, a patient with pyonephrosis may have severe flank pain, fever, elevated white blood cell (WBC) count, and other signs of infection along with a stone and hydronephrosis identified on an imaging study.6 In the elective setting, PCN is performed to provide preoperative access to the renal collecting system in patients about to undergo percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PNL).7

Ureteral strictures also may be treated by percutaneous methods. Causes of strictures include radiation, retroperitoneal fibrosis, prior instrumentation, and fistulae. These patients may present with one or many signs and symptoms: fever, flank pain, renal failure, hydronephrosis, or urinoma formation on imaging studies.

Patients with renal allografts (transplants) may present with urine leaks, ischemic ureter, and obstruction and may be treated with PCN. Percutaneous procedures also are used to perform Whitaker tests (see Chapter 9), which measure the pressure gradient across a ureteral stenosis, to infuse antibiotics for fungal infections, to infuse agents for stone dissolution, and to provide access for removal of encrusted stents.8–10

Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

The need foraPCNisgenerally straightforward. The presence or absence of hydronephrosis can be determined quickly, safely, and with certainty by ultrasound orCT scanning. The proper clinical setting will confirm the need for the procedure. Hydronephrosis can be due to reflux, however, and does not always mean obstruction or translate into a need for a PCN. Furthermore, it is important to determine whenaPCNiselective and whenthe procedure needs to be performed as an emergency.

FIGURE 24-1. Percutaneous nephrostomy (PCN) placed to relieve ureteral obstruction resulting from cervical carcinoma. Note that the tube enters the collecting system below the costal margin through a posterior mid–lower pole calyx, which provides safe avascular access and a good “pushing angle” for future attempts at ureteral stent placement. Irregularity of upper ureter is due to ureteritis cystica.

Some patients have chronic hydronephrosis (determined from serial imaging studies) with a new elevation of the BUN and creatinine levels. In the patient with a solitary kidney, PCN is certainly indicated to preserve the remaining renal parenchyma. The same is true when one kidney demonstrates cortical atrophy and the other demonstrates relatively normal cortex: The more normal kidney should be decompressed. When bilateral cortical atrophy and hydronephrosis are present, progressive renal failure may not be stabilized or improved by decompression. Sometimes the only way to prove or disprove the value of decompression in preserving renal function is to perform the PCN and then remove the tube if the kidney does not produce urine or if the function on a nuclear medicine scan does not improve.

The opposite situation, in which the BUN and creatinine levels are rising but there is minimal hydronephrosis, also can occur. Although the renal failure is most likely due to medical renal disease, there is also the possibility of obstruction without dilation, which occurs when the kidney shuts down before it dilates. This type of obstruction has been reported in patients with prostatic carcinoma.11 Although this situation is unusual, it should be kept in mind because percutaneous decompression will improve renal function.

PCN should be performed as an emergency procedure12 in the following situations:

- 1. In the setting of high fever and elevated WBC count or frank sepsis, when the patient is suspected of having pus in the kidney: This is usually seen in a patient with hydronephrosis and an identifiable obstructing calculus causing urosepsis.

- 2. Iatrogenic trauma to the ureter that is recognized when it happens: If the urologist calls from the operating room and says that the ureter has been dissected, the patient should have a PCN to divert the urine and to avoid urinoma formation. Stent placement to preserve the integrity of the ureter and avoid stricture formation should be attempted.

- 3. Severe unmanageable flank pain resulting from an obstructing calculus or steinstrasse from a preceding extracorporeal shock-wave lithotripsy (ESWL) treatment: Decompression via a PCN (antegrade approach) or a ureteral stent placed by the urologist (retrograde approach) will provide pain relief.

- 4. Acute renal failure resulting from bilateral obstruction or obstruction in a solitary kidney: This procedure should be done urgently to preserve renal parenchyma and to induce a diuresis to correct fluid and electrolyte imbalances.

Treatment Alternatives

Treatment Alternatives

Whenever possible, the retrograde approach (i.e., opposite the direction of flow of urine) to ureteral stent placement is preferable to the antegrade approach. The retrograde approach, usually performed by the urologist, has the advantage of avoiding creation of an 8 or 10 Fr hole extending from the flank to the kidney, which can be complicated by bleeding and may produce pain. Retrograde ureteral stent placement is also a one-step procedure, whereas antegrade stent placement may require at least two visits to the radiology department: first for the initial nephrostomy and then for placement of the stent. Until the antegrade stent has been placed and the urine is free of blood, the patient must wear an external nephrostomy bag (so that the stent will not occlude from blood clots). Patients who have small ureteral calculi and require stents with normal bladders and visible ureteral orifices and patients undergoing precautionary ureteral stenting prior to bowel or pelvic surgery are examples of two situations in which retrograde ureteral stenting is preferable to the antegrade approach and is usually successful. In patients with malignant obstructions at the level of the ureterovesicle junction, the ureteral orifice often cannot be identified and attempts at retrograde stent placement will usually fail. In fact, many patients undergo percutaneous procedures after failure of the retrograde approach.

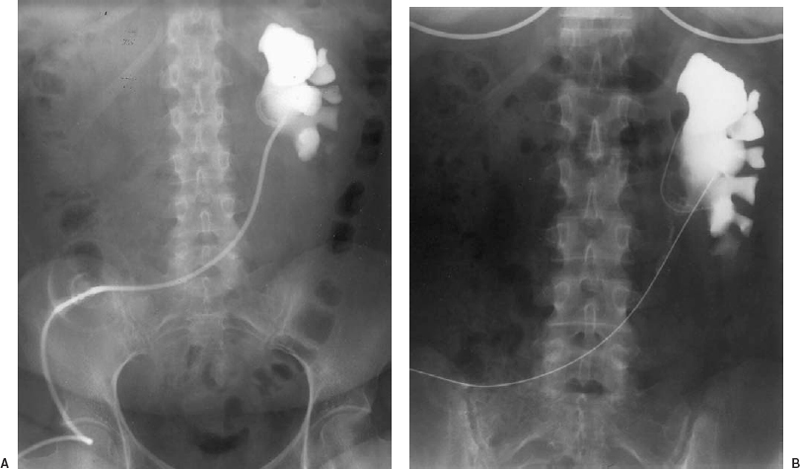

FIGURE 24-2. A: “Upside down” percutaneous nephrostomy (PCN) to relieve hydronephrosis in a patient with an ileal conduit. After standard PCN access is achieved, a guidewire is maneuvered down the ureter into the conduit. The guidewire is retrieved from the conduit, and an “upside down” PCN is inserted. The external portion of the PCN lies in the ostomy bag rather than exiting the flank. Completely internalized stents occlude rapidly because of mucus production in the conduit. B: Tubes can be changed easily over a guidewire from the ostomy site.

Although retrograde approaches usually are performed by the urologist, they also can be performed by the interventional radiologist. This approach is easier in female patients because the urethra is shorter than in male patients. On occasion, the urologist will be able to advance a small catheter from the urethra into the ureter but will not be able to place a true stent. If the patient is transferred to the radiology suite with the catheter still in place, the interventionalist often will succeed in retrograde placement of the stent, thereby avoiding nephrostomy. Retrograde approaches also can be useful in patients with ileal conduits and other diversionary pouches (Fig. 24-2).13

Actually, most cases of stone disease that require intervention usually are treated by ESWL rather than by PNL; however, when ESWL is not applicable or has failed, percutaneous approaches are used. Situationsinwhich ESWL is not applicable are stones larger than 3 cm, cysteine stones, lucent or infected stones, large staghorn calculi, and stones trapped in an infected calyx. Open surgery is rarely necessary for the treatment of stone disease.

Imaging Workup

Imaging Workup

When a patient is referred for a PCN to relieve obstruction, an imaging study is neededto prove hydronephrosis. This may be done quickly and easily by using ultrasound, which also will demonstrate cortical thickness and the level of obstruction, as well as the presence of stones and potential technical difficulties such as large cysts, urinomas, and duplicated collecting systems. The ultrasound machine also can be wheeled into the interventional suite and can be very helpfulin localizing the kidney. The more costly CT scan gives the same information as the ultrasound, but it also shows the level of the kidney, which, if it is located unexpectedly high or low, could make fluoroscopic localization difficult. Sometimes an excretory urogram is performed just before the PCN (usually in stone cases); if there is contrast in the collecting system of the obstructed kidney, access to the collecting system is facilitated.

PCNs often are performed to provide access to the renal collecting system prior to PNL.14,15 Excretory urograms and retrograde pyelograms are best for locating the number and size of stones in the intrarenal collecting system before access for removal. When outpatients arrive for procedures, often only a clinical history has been provided but no studies are available. In this situation, good prone scout films with 30-degree obliques before and after contrast is injected should be obtained, either intravenously or through an antegrade pyelogram (direct skinny-needle puncture into the renal pelvis).

Interventions: Percutaneous Nephrostomy and Ureteral Stenting

Interventions: Percutaneous Nephrostomy and Ureteral Stenting

The approach to the PCN could be titled, “Why are we doing this case?” The goal of the procedure will determine how general or specific the puncture into the collecting system needs to be. The main goals of PCN are to relieve obstruction (the simplest approach), to stent the ureter (the more specific approach), and to provide access for stone removal (the approach that requires the most planning and is the most specific).

PCN to relieve obstruction

When the goal of the PCN is to relieve obstruction by providing external drainage without planning any further interventions, a nonspecific approach will suffice. Essentially any access from the flank to the intrarenal collecting system will be sufficient as long as the tube traverses the renal cortex (to anchor the tube) and enters through a calyx (an avascular area that does not have large crossing vessels) and direct pelvic punctures are avoided (see Fig. 24-1

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree