SIR class

Description

Minor

A

No therapy, no consequences

B

Nominal therapy, observation, no consequences, includes overnight admission for observation only

Major

C

Required therapy, minor hospitalisation (<48 h)

D

Major therapy, unplanned increase in level of care, prolonged hospitalisation (≥48 h)

E

Permanent adverse sequelae

F

Death

Complications of angiography

Non-target embolisation

Post-embolisation syndrome (PES) requiring prolonged admission, readmission or escalation of care

Pelvic infection

Fibroid passage requiring intervention

Ovarian failure

Sexual dysfunction

Radiation injury

Adverse drug reaction

Pulmonary embolism (PE)/Deep vein thrombosis (DVT).

2 Overall Complication Rates

There are a large number of observational studies of UAE and comparative studies of UAE versus hysterectomy or myomectomy. The largest patient cohorts to date are two prospective, multicentre registries: UK Uterine Artery Embolisation for Fibroids Registry set up by the British Society of Interventional Radiology (BSIR) (O’Grady et al. 2009), and the Fibroid Registry for Outcomes Data (FIBROID) registry established by the SIR (Worthington-Kirsch et al. 2005). The 59 centres that participated in the BSIR registry recorded data on 1387 procedures and found an overall pre-discharge complication rate of 2 %, of which only 1 % resulted in delayed discharge, and 14 % post-discharge adverse events. The FIBROID registry consists of 3160 patients from 72 sites and reported an in-hospital complication rate of 0.66 % and 30 days post-discharge rate of 4.8 %.

A large prospective series of 400 patients by Spies et al. reported an overall complication rate of 8.5 % and a major complication rate of 1.25 %. (Spies et al. 2002). Several randomised controlled trials have described major complications in up to 15 % of patients following UAE (Pinto et al. 2003; Mara et al. 2006; Volkers et al. 2006; Manyonda et al. 2011; Dutton et al. 2007; Edwards et al. 2007) and smaller observational studies have also reported higher complication rates of 11–26 % (Razavi et al. 2003; Goodwin et al. 2006; Siskin et al. 2006). On the other hand, the most recently published prospective randomised trial (FUME) reported a much lower major complication rate of 2.9 % (Manyonda et al. 2011). A summary of complication rates from various reports are outlined in Table 2.

Table 2

Complication rates of observational and comparative studies of UAE

Study | Years | N | Complications n (%) | Reported complications | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Total | Major | ||||

Goodwin et al. (1999) | 1999 | 60 | 13 (21.7) | 1 (1.7) | Hysterectomy for infection 1 |

Siskin et al. (2000) | 2000 | 49 | 2 (4.1) | 2 (4.1) | Uterine/fibroid necrosis 1, prolonged fever 1 |

Spies et al. (2001a) | 2001 | 200 | 14 (7) | 1 (0.5) | PE 1 |

Spies et al. (2002) | 2002 | 400 | 34 (8.5) | 5 (1.25) | PE 1, arterial thrombosis 1, fibroid expulsion 3 |

Pron et al. (2003a) | 2003 | 538 | – | – | Amenorrhoea 21 |

FIBROID Worthington-Kirsch et al. (2005) | 2005 | 3160 | – | 20 (0.66)a 135 (4.8)b | Prolonged pain 6, infection/possible infection 17, fibroid passage 19 |

Goodwin et al. (2006) | 2006 | 149 | 33 (22.1) | – | Fibroid expulsion 3, UTI 4, post-embolisation syndrome 4 |

Mara et al. (2006) | 2006 | 30 | 18 (60) | 3 (10) | – |

Siskin et al. (2006) | 2006 | 77 | 20 (26) | 0 | – |

EMMY Volkers et al. (2006) | 2006 | 81 | 29 (35.8)a | (4.9)a | PE 1, fibroid expulsion 1, sepsis 1, UTI 2, post-embolisation syndrome 2 |

51 (63)b | (11.1)c | ||||

REST Edwards et al. (2007) | 2006 | 106 | – | 9 (12) | Pelvic infection 2, fibroid expulsion 3, necrotic fibroid 1, pelvic abscess 1, transient amenorrhoea 2 |

HOPEFUL Dutton et al. (2007) | 2007 | 649 | 22 (19) | – | Amenorrhoea 1, sepsis 17 |

BSIR registry O’Grady et al. (2009) | 2009 | 1387 | – | 15 (1)a | Respiratory arrest 1, fibroid expulsion 31, DVT 1, uterine infection 21 |

191 (14)d | |||||

FUME Manyonda et al. (2011) | 2011 | 67 | – | 2 (2.9) | Pelvic sepsis 1, fibroid expulsion 1 |

The joint standards of Practice Committee of the Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiological Society of Europe (CIRSE) and the Society of Interventional Radiology (SIR) have produced quality improvement guidelines for UAE (Hovsepian et al. 2009). The reported complication rates and suggested threshold rates are outlined in Table 3.

Table 3

Complication rates for UAE (CIRSE and SIR quality improvement guidelines) (Hovsepian et al. 2009)

Complication | Reported rate (%) | Suggested threshold (%) |

|---|---|---|

Transient amenorrhoea | 5–10 | 10 |

Permanent amenorrhoea <45yrs | 0–3 | 3 |

Permanent amenorrhoea >45 yrs | 7–14 | 15 |

Transcervical fibroid expulsion | 0–3 | 5 |

Non-infectious endometritis | 1–2 | 2 |

Endometrial or uterine infection | 1–2 | 2 |

Deep venous thrombosis or pulmonary embolus | <1 | 2 |

Uterine necrosis | <1 | 1 |

Non-target embolisation | <1 | <1 |

3 Complications of Angiography

These are immediate complications related to the technical aspects of the procedure and include haematoma, contrast reaction, arterial dissection/rupture and femoral nerve injury. Such complications are rare in UAE as the patients are young with no underlying arterial disease and procedural anticoagulation with heparin is not required. Groin haematoma has been reported in 0.25–20 % of patients (Pinto et al. 2003; Spies et al. 2002; Manyonda et al. 2011; Goodwin et al. 2006; Siskin et al. 2006; Dutton et al. 2007), arterial injury has been seen in up to 0.5–10 % (Pinto et al. 2003; Spies et al. 2002; Pelage et al. 2000), femoral nerve injury in up to 1.6 % (Razavi et al. 2003; Spies et al. 2002) and adverse reaction to contrast medium in up to 2.5 % (Spies et al. 2002; Manyonda et al. 2011; Dutton et al. 2007).

The majority of these complications are minor requiring either no secondary intervention or overnight stay for observation. However, one of the largest case series of 400 consecutive patients reported a case of bilateral iliac artery thrombosis, which occurred during embolisation and required thrombolysis and intensive care therapy (Spies et al. 2002). This is a highly unusual complication which has not been reported elsewhere and unfortunately no detailed explanation has been offered by the authors.

4 Non-target Embolisation

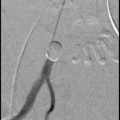

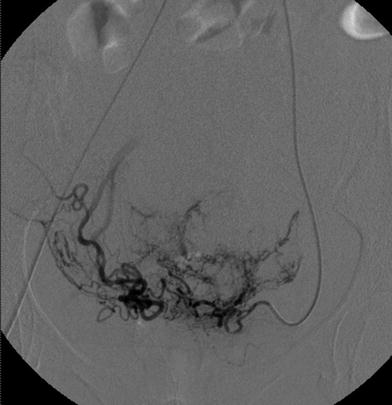

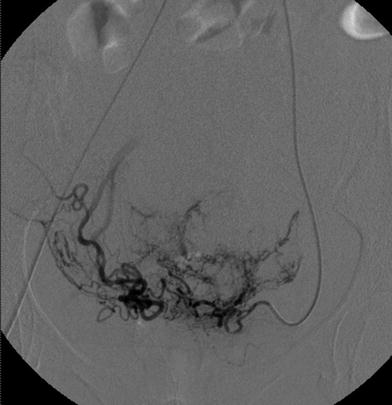

There are multiple branches of the internal iliac artery which arise close together and there are known collateral communications with the ovarian arteries and contralateral uterine artery branches (Fig. 1). Therefore, it is important to be aware of the variations in normal anatomy and the presence of any arterial anastomoses that may open up during embolisation as the haemodynamics of the pelvic circulation is altered.

Fig. 1

Selective angiogram of the left uterine artery shows contralateral retrograde filling of the right uterine artery (Courtesy of Dr A Pankhania)

There are several reports of non-target embolisation during UAE. One woman was readmitted 8 days after bilateral UAE with profuse watery vaginal discharge and complete urinary incontinence, secondary to widespread cervical and vaginal necrosis with fistulation into the urinary bladder (El-Shalakany et al. 2003). She required hysterectomy and surgical closure of the bladder defect. The authors speculated that the extensive involvement of the vesical and vaginal blood supply may be secondary to thrombosis, occurring as a result of inflammation associated with ischaemic necrosis of the embolised fibroids. Another report described a patient presenting 4 days after-unilateral UAE with dysuria and purulent vaginal discharge, secondary to areas of necrosis in the cervix and ipsilateral lower vaginal wall (Löwenstein et al. 2004). She was successfully treated conservatively with analgesia and antibiotics. Another woman developed 2 areas of full-thickness buttock necrosis following UAE that required surgical debridement (Dietz et al. 2004).

It has also been suggested that UAE may reduce a woman’s ability to achieve orgasm (Lai et al. 2000). The authors speculate that disrupting the uterine blood flow may result in altered perfusion of the uterovaginal plexus, which is responsible for sensory and autonomic innervation of the pelvic organs. Inadvertent non-target embolisation of the cervicovaginal branches, which arise from the uterine arteries, may contribute to the ischaemic effect. In contrast to this case report, a study of 141 pre-menopausal women who underwent UAE for symptomatic fibroids observed significant improvements in sexual function and well being while problems associated with orgasm and pain reduced (Voogt et al. 2008). Similar improvements in sexual activity and satisfaction following UAE have been described in other studies (Hehenkamp et al. 2007; Smith et al. 2004).

A fatal case of non-target embolisation has been reported in a patient that required 22 syringes of embolic particles to treat a 10 cm uterine fibroid. This patient developed multi-organ failure following UAE and the autopsy report stated the presence of an arteriovenous malformation within the leiomyoma, a patent foramen ovale and embolic particles in the lungs, heart and kidneys. Another fatal case was reported in a patient who underwent UAE with 11 vials of 500–700 μm (de Blok et al. 2003). The post-mortem showed diffuse necrosis of the pelvic organs and microspheres were found in the main uterine arteries as well as the smaller branches within the myometrium, leiomyomata, vagina and parametria.

As a general rule, large quantities of embolic agents and the use of small embolic particles should be avoided in order to minimise complications of non-target embolisation. The need for an unusually large volume of embolic agents should alert the operator of the possibility of an abnormal collateral supply or anastomotic communication. Careful scrutiny of images during embolisation should be performed to ensure the particles are being delivered to the appropriate end-organ, as evidence suggests that the amount of embolic particles is fairly similar in all cases and is not proportional to the fibroid or uterine size (Parthipun et al. 2010).

5 Post-embolisation Syndrome

Post-embolisation syndrome (PES) is characterised by low-grade fever, pain, leucocytosis and malaise. It occurs during the first 7–10 days following the procedure. And is an expected outcome after embolisation. PES should be anticipated in all women undergoing UAE and it becomes a complication only if the symptoms are severe i.e. necessitating readmission, prolonged admission beyond 48 h or unexpected escalation in the level of care (Goodwin et al. 2003; Bratby and Belli 2008). In early series of UAE, it was one of the main reasons for re-admission after discharge (Mehta et al. 2002). PES is now better understood although distinguishing this syndrome from an acute infection can be difficult as the signs and symptoms may mimic those of acute sepsis. Therefore, it is important to counsel women prior to UAE to warn them of PES symptoms in the early post-procedural period. In addition, they should be advised to seek urgent medical assistance if similar symptoms occur beyond the first 1–2 weeks in order to avoid delay in diagnosis of acute infection.

6 Pelvic Infection and Sepsis

Any pelvic sepsis is a contraindication to UAE. Although pelvic infection is uncommon following UAE, it can be a serious complication which may lead to sepsis, emergency hysterectomy or even death. Although there is no consensus on the use of prophylactic antibiotics, there is some evidence from the HOPEFUL trial and the BSIR registry that this may be beneficial (Dutton et al. 2007; O’Grady et al. 2009) and peri-procedural antibiotics are often administered in an effort to avoid infection.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree