Fig. 1

Gallbladder mucosa showing low-grade dysplasia. The epithelium shows mild nuclear atypia, nuclear stratification, and hyperchromasia. However, the polarity of the cells is maintained, thus arguing against the diagnosis of high-grade dysplasia

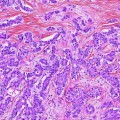

Fig. 2

A high-powered view of the lining epithelium of the gallbladder. The image shows high-grade dysplasia. Note the marked nuclear atypia, occasional prominent nucleoli, and mitotic figures, as well as the loss in cells polarity

There is overlap between these two grades of dysplasia, and, although untested, there is likely to be a significant interobserver variability. Proponents of the term BilIN, generally used to designate dysplasia in the biliary tree, recognize three grades of dysplasia—BilIN-1, BilIN-2, and BilIN-3, corresponding to low-, intermediate- and high-grade dysplasia [12]. However, this grading system also suffers from similar shortcomings—a relatively high degree of interobserver variability, likely even higher than a two-tier system of grading.

2.1.4 Clinical Significance and Natural History

No further therapy is generally required when dysplasia is identified during routine cholecystectomy [13]. As this recommendation is predicated on the absence of invasive carcinoma, it is important that the pathologist thoroughly evaluates the resected specimen; this especially applies to cases with extensive high-grade dysplasia. However, data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program of the National Cancer Institute suggest that one-third of patients with carcinoma in situ of the gallbladder died of tumor after 10 years [14]. This may be the result of an unsampled invasive component of the tumor. However, a more likely scenario is the genesis of a second malignancy of the biliary tract, a consequence of a field defect within the biliary system.

2.2 Mass-Forming Precursor Lesions of Gallbladder Carcinoma (Adenoma)

There are several analogies that could be drawn between adenomas of the colon and those of the gallbladder; most significantly, both lesions may progress to invasive carcinoma. However, in contrast to colonic carcinoma, only a minority of gallbladder carcinomas arise from adenomas [6].

Adenomas of the gallbladder are a poorly characterized entity, primarily because of their low prevalence. A wide array of terms have been used to designate adenomas of the gallbladder including “pyloric gland adenoma,” “papillary adenoma,” “tubular papillary adenoma,” “papillary neoplasm,” “papillary carcinoma,” and “intracystic papillary neoplasm.” A selection of these terms is based on growth patterns, while others are based on the morphological appearance of the lining epithelium and its resemblance to epithelium lining the gastrointestinal tract. In a recent analysis of 123 gallbladder adenomas, Adsay and colleagues suggest the unifying term intracholecystic papillary-tubular neoplasm (ICPN) to encompass all neoplastic mass-forming precursor lesions of gallbladder [6]. This argument has merit since all of these mass-forming neoplasms of the gallbladder are associated with a significant risk of invasion. However, there appeared to be some minor variations in the risk of invasive carcinoma among the various subcategories of gallbladder adenomas. It is important to emphasize that some de novo invasive gallbladder carcinomas may present as a polypoid mass. Therefore, pathologists must draw a clear distinction between this entity, polypoidal carcinoma, and a precursor neoplastic polyp associated with an invasive carcinoma; the latter category is associated with a slightly better prognosis.

2.2.1 Gross Features of Gallbladder Polyps

The polyps could be either sessile or pedunculated; the latter are often easily detached from the underlying wall and thus may be mistaken for stones. Interestingly, only about 20 % of neoplastic gallbladder polyps are associated with gallstones.

2.2.2 Morphologic Variants of Gallbladder Adenomas

Based on the architectural pattern of growth, adenomas could be classified into (1) tubular, (2) papillary, and (3) tubulopapillary [6]. In comparison with the tubular pattern, adenomas with a papillary growth pattern are associated with an increased risk of invasion.

By definition, all neoplastic gallbladder polyps show low-grade dysplasia. However, a substantial population of polyps also reveal high-grade dysplasia, characterized by marked cytological atypia and/or architectural abnormalities, such as crowding of glands and a cribriform pattern of growth. Polyps with extensive high-grade dysplasia are more likely to show invasive carcinoma.

2.2.3 Variants Based on Cell Lineage

Analogies have been drawn between intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs) of the pancreas and “adenomas” of the gallbladder. Similar to IPMNs, four variants of gallbladder polyps are recognized [6, 15].

However, unlike IPMNs of the pancreas, the majority of which are easily classified into one of these four lineages (gastric, intestinal, pancreatobiliary, and oncocytic), these preneoplastic lesions in the gallbladder are often difficult to classify, and many of these polyps exhibit more than one cell lineage.

1.

Biliary: The epithelium lining these polyps resembles biliary epithelium. The biliary subtype appears to be associated with a higher incidence of invasive carcinoma.

2.

Gastric and pyloric types of adenomas: These polyps are lined by gastric-type epithelium, characterized by basal nuclei and abundant apical pale cytoplasm. The pyloric variant shows small caliber glands lined by cells containing abundant intracellular mucin (Fig. 3). This phenotype is characterized by the presence of strong and diffuse reactivity for Muc6.

Fig. 3

a Low-power view of a gallbladder adenoma. The adenoma is composed of predominantly small glands, although occasional larger glandular structures are also present. Attachment to the underlying gallbladder wall is not identified in this image. b High-powered view of a gallbladder adenoma with mild dysplasia. The glands are lined by cuboidal to columnar cells with pale eosinophilic cytoplasm, an appearance that resembles pyloric glands. This lesion could be classified as a pyloric gland adenoma

3.

Intestinal type: These polyps are lined by epithelium that is similar to colonic adenomas. Immunohistochemically, these polyps are characterized by the presence of keratin 20 and CDX2 reactivity. Absence of keratin 7 is also characteristic of this phenotype.

4.

Oncocytic variant: This is the least common of the four subtypes and is characterized by the presence of tumor cells containing abundant pink cytoplasm.

2.2.4 Prognosis

Adenomas of the gallbladder should be viewed as a premalignant lesion. The prognosis of patients with polypoidal precursor lesions of the gallbladder is significantly better than invasive gallbladder carcinoma. In one recent analysis, non-invasive adenomas and papillary carcinomas had a 3-year and 5-year survival of 90 % and 78 %, respectively [6].

2.3 Intracystic Papillary Neoplasms

The World Health Organization’s classification of tumors of the digestive system recognizes an intracystic papillary neoplasm as a distinct entity and distinguishes them from adenomas of the gallbladder [16]. Intracystic papillary neoplasms show a prominent intraluminal proliferation of papillary epithelium, generally with high-grade atypia (Fig. 4). However, in many cases, there is no clear distinction between this entity and an adenoma of the gallbladder. Similar to the adenomas of the gallbladder, intracystic papillary neoplasms that lack invasion are associated with an excellent prognosis [17].

Fig. 4

Intracystic papillary neoplasm of the gallbladder

2.4 Mucinous Cystic Neoplasms

Mucinous cystic neoplasms are seen in adult females. This neoplasm is more frequently seen in the pancreas; the hepatic and gallbladder counterparts are extremely uncommon [18]. Histologically, these cystic neoplasms are lined by mucinous epithelium with varying grades of atypia. These neoplasms are defined by the presence of ovarian-type stroma. Similar to the pancreas, non-invasive lesions are associated with an excellent outcome, while invasive adenocarcinomas arising in mucinous cystic neoplasms are associated with a risk of metastasis and death.

2.5 Other Polypoid Lesions of the Gallbladder

Neoplastic polyps constitute only a minority of gallbladder polyps; the majority of gallbladder polyps are non-neoplastic. The two most common non-neoplastic polyps of the gallbladder are cholesterol polyp and adenomyoma.

2.5.1 Cholesterol Polyp

Cholesterol polyps are either sessile or, less commonly, pedunculated. They generally measure less than 1 cm in size [19]. Grossly, the lesion has a bright yellow cut surface. Microscopically, the polyps are lined by benign-appearing biliary epithelium that is often organized in a papillary architecture. The papillary structures are characteristically occupied by sheets of foamy histiocytes, which contain abundant lipid. These polyps have no neoplastic potential.

2.5.2 Adenomyomatous Polyps

Adenomyomatous polyps generally do not form an intraluminal nodule; instead, this lesion presents as a mural thickening or a well-defined mural nodule. Histologically, the nodule is composed of dilated glandular structures that often resemble Rokitansky–Aschoff sinuses. The glands are surrounded by fibrocollagenous tissue and interspersed smooth muscle [20]. Like the cholesterol polyp, adenomyomatous polyps are benign and have not been reported to undergo malignant degeneration. However, high-grade dysplasia may involve the lesion and, thus, may mimic an invasive carcinoma.

2.5.3 Polypoidal Pyloric Gland Hyperplasia

Pyloric gland hyperplasia is a common form of metaplasia of the gallbladder. Occasionally, circumscribed aggregates of pyloric glands may mimic an adenoma, specifically a pyloric-type adenoma. Similar to the lesions listed above, this metaplastic lesion is not associated with an elevated risk of gallbladder malignancy.

2.6 Variants of Cholecystitis Associated with Risk of Gallbladder Carcinoma

2.6.1 Porcelain Gallbladder

Porcelain gallbladder describes the gross appearance of a gallbladder with extensive calcification, resulting in a brittle consistency and blue discoloration. There is much variation in the literature about the frequency with which invasive carcinoma arises in these gallbladders; however, it seems that the pattern of gallbladder wall calcification correlates with the risk of developing carcinoma such that approximately 5 % of gallbladders with diffuse, transmural calcification harbor carcinoma [21].

2.6.2 Hyalinizing Cholecystitis

Hyalinizing cholecystitis is an uncommon variant of cholecystitis that is characterized by a dense, paucicellular hyaline-type fibrosis of the gallbladder wall, which thins the wall and effaces the normal histologic structures. In contrast to porcelain gallbladders, only focal mucosal or intramural calcifications are typically present and about 15 % of cases are associated with invasive carcinoma [22]. These carcinomas are often subtle and difficult to diagnose as only few widely spaced malignant glands are present and the surface mucosa can be denuded; in these cases, extensive sampling of the gallbladder is recommended.

3 Gallbladder Carcinoma

Most malignant epithelial neoplasms of the extrahepatic biliary tract arise within the gallbladder. The majority of gallbladder carcinomas are adenocarcinomas, most commonly of the biliary type, although several other histologic subtypes have been defined by the World Health Organization [16] (Table 1).

Epithelial tumors | Mesenchymal tumors |

|---|---|

Benign | Benign |

Cholesterol polyp | Granular cell tumor |

Adenomyoma | Leiomyoma |

Premalignant lesions | Malignant |

Adenoma (tubular, papillary, or tubulopapillary type) | Rhabdomyosarcoma |

Biliary intraepithelial neoplasia (BilIN) | Leiomyosarcoma |

Intracystic papillary neoplasm | Lymphoma |

Mucinous cystic neoplasm | Metastases |

Malignant | |

Adenocarcinoma, biliary type | |

Adenocarcinoma, gastric foveolar type | |

Adenocarcinoma, intestinal type | |

Clear cell adenocarcinoma | |

Hepatoid adenocarcinoma | |

Mucinous adenocarcinoma | |

Signet ring cell carcinoma | |

Cribriform carcinoma | |

Adenosquamous carcinoma | |

Squamous cell carcinoma | |

Carcinosarcoma | |

Undifferentiated carcinoma | |

Neuroendocrine neoplasms | |

Neuroendocrine tumor (NET) | |

NET, grade 1 (carcinoid) | |

NET, grade 2 | |

Neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC) | |

Large cell NEC | |

Small cell NEC | |

Mixed adenoneuroendocrine carcinoma | |

Goblet cell carcinoid | |

Tubular carcinoid |

3.1 Gross Features

Most gallbladder carcinomas arise within the gallbladder fundus, with the body and neck being affected less often. However, as these tumors are often ill-defined, the location of origin and boundaries of the tumor can be difficult to determine grossly. Gallbladder carcinomas appear as a firm, infiltrative gray-white mass within the wall of the gallbladder. Mucinous and signet ring carcinomas can have a mucoid or gelatinous cut surface. The gallbladder may be enlarged secondary to the presence of the mass or, when obstructed by a proximal mass, may be collapsed. Occasionally, carcinomas (most notably signet ring cell adenocarcinoma) may cause diffuse thickening of the gallbladder wall, mimicking fibrosis associated with chronic cholecystitis. Carcinomas may also show a polypoid or exophytic component, which, when present, is typically soft, granular, and friable.

3.2 Histologic Features

3.2.1 Adenocarcinoma

Most gallbladder adenocarcinomas are composed of irregularly dispersed, infiltrative glands. Histologic grading of adenocarcinomas depends on the degree of glandular differentiation; however, most tumors are well to moderately differentiated. The glands are often separated by prominent desmoplastic stroma, which may also contain an inflammatory infiltrate. These glands most commonly resemble biliary epithelium and are lined by cuboidal to columnar cells. There is often marked nuclear atypia, out of proportion to the degree of glandular differentiation (Fig. 5). Cytoplasmic and luminal mucin may be present. Goblet, neuroendocrine, and Paneth cells may also be seen in varying numbers, although they are more commonly present in adenocarcinomas with intestinal differentiation. Intestinal-type adenocarcinomas of the gallbladder may also be composed of tubules lined by pseudostratified, elongated, and hyperchromatic nuclei and may be accompanied by “dirty” necrosis, thereby resembling colonic adenocarcinoma. Gastric foveolar-type adenocarcinoma, which is less common than the biliary and intestinal types, characteristically shows well-differentiated glands composed of columnar cells with basally located nuclei and mucin-filled cytoplasm (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5

Invasive adenocarcinoma of the gallbladder

Fig. 6

Invasive gallbladder carcinoma with a gastric phenotype

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree