(TGF ), assessed by immunostaining, are elevated in human BTC including GBC [22, 23]. Accumulating evidence suggests that COX-2, an inducible enzyme responsible for conversion of arachidonic acid to prostaglandins, may play a variety of roles in the gastrointestinal tract including pathogenic processes such as neoplasia [24]. A recent study demonstrated a relationship between erbB2 overexpression and COX-2 upregulation in human colorectal cancer cells [25]. Elevated COX-2 expression has been demonstrated in well-differentiated human hepatocellular carcinoma [26, 27] and GBC [28] compared with low or non-detectable COX-2 expression in poorly differentiated tumors. Very recently, Sirica’s group reported a strong positive correlation between the immunostaining intensities of erbB2 and COX-2 in BTC. COX-2 was observed not only in the furan rat cholangiocarcinoma model, but also in human cholangiocarcinomas [29], supporting the possibility that erbB2 plays a key role in regulating COX-2 expression in neoplastic and precancerous biliary tract epithelial cells. Grossman et al. [30] reported a specific COX-2 inhibitor, but not COX-1 inhibitor, decreased mitogenesis, and increased human gallbladder cell apoptosis associated with decreased prostaglandin E2 (PGE2). This suggests that the COX enzymes and the prostanoids may play a role in the development of gallbladder cancer and that COX-2 inhibitors may have a therapeutic role in gallbladder neoplasms [30].

), assessed by immunostaining, are elevated in human BTC including GBC [22, 23]. Accumulating evidence suggests that COX-2, an inducible enzyme responsible for conversion of arachidonic acid to prostaglandins, may play a variety of roles in the gastrointestinal tract including pathogenic processes such as neoplasia [24]. A recent study demonstrated a relationship between erbB2 overexpression and COX-2 upregulation in human colorectal cancer cells [25]. Elevated COX-2 expression has been demonstrated in well-differentiated human hepatocellular carcinoma [26, 27] and GBC [28] compared with low or non-detectable COX-2 expression in poorly differentiated tumors. Very recently, Sirica’s group reported a strong positive correlation between the immunostaining intensities of erbB2 and COX-2 in BTC. COX-2 was observed not only in the furan rat cholangiocarcinoma model, but also in human cholangiocarcinomas [29], supporting the possibility that erbB2 plays a key role in regulating COX-2 expression in neoplastic and precancerous biliary tract epithelial cells. Grossman et al. [30] reported a specific COX-2 inhibitor, but not COX-1 inhibitor, decreased mitogenesis, and increased human gallbladder cell apoptosis associated with decreased prostaglandin E2 (PGE2). This suggests that the COX enzymes and the prostanoids may play a role in the development of gallbladder cancer and that COX-2 inhibitors may have a therapeutic role in gallbladder neoplasms [30].

3 Role of ErbB RTKs and Their Downstream Signaling Pathways in the Development of BTC

3.1 ErbB2 and EGFR in Human BTC

3.2 erbB RTK Family

(TGF-

(TGF- ), heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor (HB-EGF), amphiregulin (AR), betacellulin [45, 46], epigen (EP), and epiregulin (EREG). The neuregulin subfamily consists of various isoforms referred to as 1–4. These ligands bind to erbB4 and/or erbB3. Betacellulin, HB-EGF, and epiregulin have also been shown to bind to erbB4. Ligand-dependent activation of erbB family receptors can lead to heterodimerization, particularly of EGFR, erbB3 and erbB4 with erbB2. To date, no ligand has been identified for erbB2. ErbB3 cannot generate signals in isolation because the kinase function of this receptor is impaired, thus relying on interaction with erbB2 for signaling.

), heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor (HB-EGF), amphiregulin (AR), betacellulin [45, 46], epigen (EP), and epiregulin (EREG). The neuregulin subfamily consists of various isoforms referred to as 1–4. These ligands bind to erbB4 and/or erbB3. Betacellulin, HB-EGF, and epiregulin have also been shown to bind to erbB4. Ligand-dependent activation of erbB family receptors can lead to heterodimerization, particularly of EGFR, erbB3 and erbB4 with erbB2. To date, no ligand has been identified for erbB2. ErbB3 cannot generate signals in isolation because the kinase function of this receptor is impaired, thus relying on interaction with erbB2 for signaling.

, signal transducer and activation of transcription (STATs), and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) pathways that are common to nearly all RTKs (Fig. 1). Although the membrane-anchored peptide can be biologically active through juxtacrine signaling, in most cases, the extracellular domain is proteolytically cleaved by a metalloprotease activity present in the cell membrane. This process is known as “ectodomain shedding” and leads to the release of the soluble growth factor, which may act in an endocrine, paracrine, or autocrine fashion [47].

, signal transducer and activation of transcription (STATs), and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) pathways that are common to nearly all RTKs (Fig. 1). Although the membrane-anchored peptide can be biologically active through juxtacrine signaling, in most cases, the extracellular domain is proteolytically cleaved by a metalloprotease activity present in the cell membrane. This process is known as “ectodomain shedding” and leads to the release of the soluble growth factor, which may act in an endocrine, paracrine, or autocrine fashion [47]. (TNF-

(TNF- )-converting enzyme, or TACE, together with ADAM10, is thought to play a central role. ADAM17 can cleave the AR, EREG, TGF-

)-converting enzyme, or TACE, together with ADAM10, is thought to play a central role. ADAM17 can cleave the AR, EREG, TGF- , and HB-EGF membrane-anchored precursors, while ADAM 10 is a key sheddase for EGF and BTC, and can also cleave the HB-HGF transmembrane precursor [45, 46, 49]. Transactivation of the EGFR by ligands of G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) is perhaps the best characterized example of EGFR activation by heterologous ligands [48]. These include angiotensin II (ANG II), lysophosphatidic acid (LPA), endothelin-I, thrombin, IL-8, and prostaglandins such as PGE2 [48]. Different mechanisms have been proposed to mediate ADAM activation by GPCRs. Elevation of the intracellular levels of Ca2 or reactive oxygen species (ROS) is likely to be involved as well as phosphorylation reactions involving protein kinase C (PKC), ERK, or c-Src [48]. As previously indicated, transactivation of the EGFR is not exclusive of GPCR-triggered signaling. Studies carried out in keratinocytes have established that the expression and release of EGFR ligands can be elicited by the cytokines TNF-

, and HB-EGF membrane-anchored precursors, while ADAM 10 is a key sheddase for EGF and BTC, and can also cleave the HB-HGF transmembrane precursor [45, 46, 49]. Transactivation of the EGFR by ligands of G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) is perhaps the best characterized example of EGFR activation by heterologous ligands [48]. These include angiotensin II (ANG II), lysophosphatidic acid (LPA), endothelin-I, thrombin, IL-8, and prostaglandins such as PGE2 [48]. Different mechanisms have been proposed to mediate ADAM activation by GPCRs. Elevation of the intracellular levels of Ca2 or reactive oxygen species (ROS) is likely to be involved as well as phosphorylation reactions involving protein kinase C (PKC), ERK, or c-Src [48]. As previously indicated, transactivation of the EGFR is not exclusive of GPCR-triggered signaling. Studies carried out in keratinocytes have established that the expression and release of EGFR ligands can be elicited by the cytokines TNF- and interferon-

and interferon- (INF-

(INF- ) [50]. This has been recently observed also for the proapoptotic factor Fas ligand (FasL). Interestingly, it was shown that transactivation of the EGFR through the secretion of ligands such as AR contributed to mediate part of the inflammatory responses to FasL in human epidermis [51] (Fig. 2).

) [50]. This has been recently observed also for the proapoptotic factor Fas ligand (FasL). Interestingly, it was shown that transactivation of the EGFR through the secretion of ligands such as AR contributed to mediate part of the inflammatory responses to FasL in human epidermis [51] (Fig. 2).

3.3 Animal Models for Human BTC

3.3.1 Background

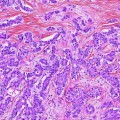

3.3.2 BK5.erbB2 Mouse Model of Gallbladder Cancer

3.3.3 Status of EGFR and ErbB2 in GBC of BK5.erbB2 Mice

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree