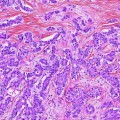

Fig. 1

Bismuth–Corlette classification of perihilar cholangiocarcinoma: I below the bifurcation of right and left hepatic ducts; II at the bifurcation of right and left hepatic ducts; IIIa at the bifurcation with extension into the right hepatic duct; IIIb at the bifurcation with extension into the right hepatic duct; and IV extension into both right and left hepatic ducts or multicentric disease

Appreciation of the tumor location within the biliary system is critical for operative management of patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Understanding of biliary anatomy as well as appreciation of nomenclature is also paramount: Biliary anatomy can be viewed proximal to distal based on either embryologic development or bile drainage. For the purpose of this chapter, we will refer to biliary bifurcation based on embryologic development and proximal to distal bile ducts based on bile drainage (i.e., proximal ducts in the liver and distal duct draining bile into the duodenum). Patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma below the bifurcation of the hepatic ducts (Bismuth–Corlette I) or just at the bifurcation (Bismuth–Corlette II) are best treated with resection of the extrahepatic bile duct and biliary reconstruction. Intraoperative pathological examination of the specimen is necessary to confirm a tumor-free margin. Types I and II hilar cholangiocarcinoma are rare; most patients prove to have extension of tumor into the biliary bifurcation and the right or left hepatic ducts or both. Cholangiocarcinoma arising in the common bile duct also often extends into the head of the pancreas.

Bismuth–Corlette classification of hilar cholangiocarcinoma involving one or both hepatic ducts is IIIa for right duct involvement, IIIb for left duct involvement, and IV for bilateral duct involvement or diffuse multifocal disease. In general, resection is possible for IIIa and IIIb tumors by right or left hepatectomy provided that the vasculature to the contralateral side (residual liver) is free from involvement.

Liver vasculature must be assessed to ensure that the remnant liver will have both arterial and portal venous inflow. Vascular involvement is best assessed by CT or MRI. Limited vascular involvement to the remnant liver can occasionally be overcome by vascular reconstruction of the hepatic artery and/or portal vein, more commonly for IIIa tumors involving the right duct than for IIIb tumors involving the left duct since the left portal vein is more amenable to reconstruction.

Generally accepted criteria for unresectability are as follows: portal and/or arterial involvement not amenable to reconstruction (all types); unilateral biliary involvement with contralateral vascular involvement not amenable to reconstruction (types IIIa and IIIb); bilateral biliary involvement of secondary ducts (type IV); and an inadequate future liver remnant. Underlying chronic liver disease—especially primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC)—usually precludes resection [2, 3]. These patients are best treated by neoadjuvant therapy and liver transplantation.

The aim of this chapter is to discuss (1) preoperative imaging of patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma to determine resectability, (2) evaluation of unresectable patients to determine candidacy for transplantation, and (3) utilization of post-transplant imaging to follow patients transplanted for hilar cholangiocarcinoma since they are prone to develop late vascular complications related to neoadjuvant radiotherapy.

1 Determination of Resectability

1.1 Cross-Sectional Imaging

Both CT and MRI are useful imaging techniques for evaluation of patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma [4–6]. The choice between CT and MRI varies due to clinician preference and institutional experience. MRI combined with MRCP is the preferred preoperative test at many institutions since it provides both cholangiography and cross-sectional imaging [7–9]. MRI allows for accurate assessment of both longitudinal and radial tumor extent in a single study. MRCP highlights biliary anatomy, delineates the level of biliary obstruction, and allows for visualization of the proximal and distal biliary ducts. Contrast MRI can detect a hilar mass (if present) and, most importantly, demonstrates vascular (arterial and venous) involvement.

Contrast multiphase CT has excellent diagnostic accuracy. CT can also demonstrate the location of the mass (if present) and determine vascular anatomy [6, 10]. Advances in CT imaging, particularly CT cholangiography and 3-dimensional reconstruction, have allowed for vast improvements in the assessment of anatomic relationships between the hepatic vasculature and biliary pathology [11, 12]. CT is somewhat better than MRI for detection of intra-abdominal and chest metastases.

ERCP is done to assess biliary anatomy, obtain an intraluminal specimen for histology and/or cytology, and to provide preoperative biliary decompression. Patients with suspected hilar cholangiocarcinoma require an experienced endoscopist. They require precise imaging, intraluminal biopsy and brush cytology for diagnosis, and biliary intubation for decompression. PTC is reserved for patients who have an inadequate ERCP (usually inadequate imaging to determine the extent of left or right duct involvement) or who are not amenable to biliary decompression with ERCP. We avoid PTC whenever possible. PTC and PTC-directed biopsy of cholangiocarcinoma can lead to tumor seeding and have been associated with higher rates of postoperative recurrence [13, 14].

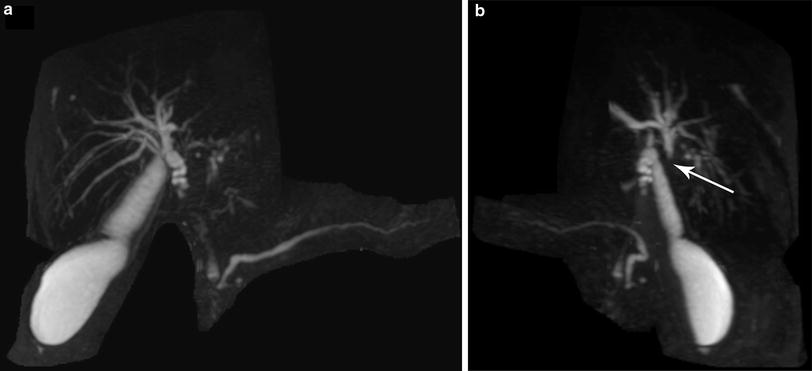

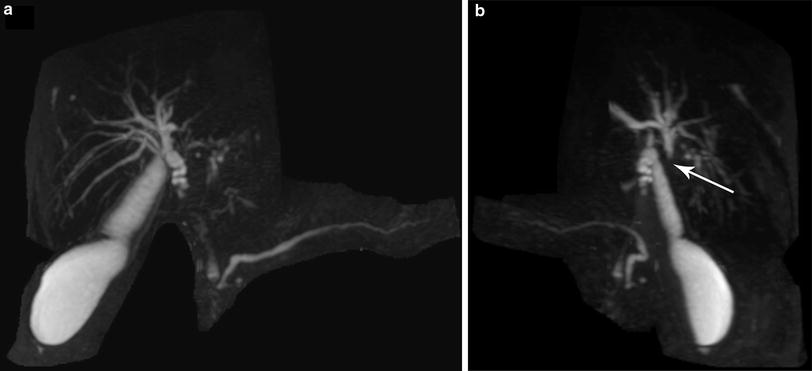

Cross-sectional imaging studies should be carefully interpreted by a multidisciplinary team. Images cannot be interpreted in isolation, and a combination of cross-sectional imaging and dynamic biliary reconstructions is needed to appreciate tumor presence, location, and vascular involvement. As an example, the lesion in (Fig. 2a) can be misinterpreted as Bismuth–Corlette I, if the MRCP is not rotated to unmask the cystic duct overlap and appreciate Bismuth–Corlette II extension (Fig. 2b). Similarly, Fig. 3 demonstrates a Bismuth–Corlette III lesion, but additional imaging interpretation is necessary to distinguish IIIA from IIIB—a critical step for operative preparation.

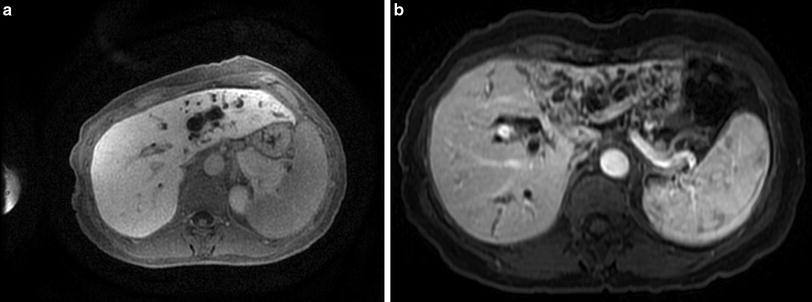

Fig. 2

Perihilar cholangiocarcinoma with the proximal extent obscured by the cystic duct (Panel a). Rotation of the MRCP reconstruction reveals proximal extent at the bifurcation (arrow)—a Type II cholangiocarcinoma (Panel b)

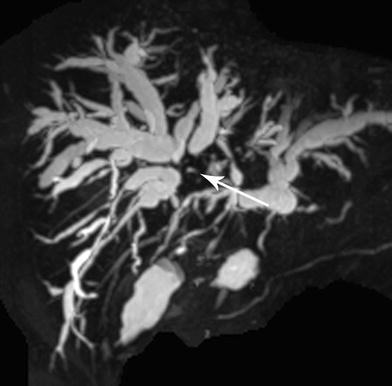

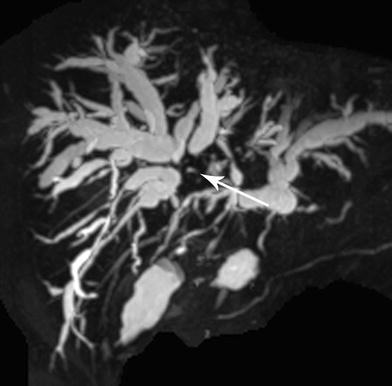

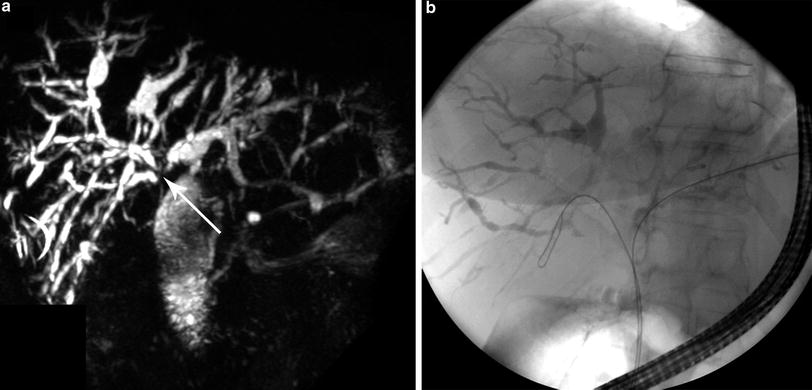

Fig. 3

MRCP revealing involvement of the ductal bifurcation (arrow) by cholangiocarcinoma. Additional rotations of the images and dynamic interpretation in conjunction with cross-sectional imaging are required to distinguish proximal ductal extent (Type IIIA vs. Type IIIB) of the cholangiocarcinoma

Both MRI and CT imaging modalities frequently fail to identify a discrete tumor mass. If visible, the mass is usually hypovascular compared to adjacent liver parenchyma and increases in intensity with delayed MRI imaging. MRCP and CT cholangiography can identify ductal irregularities and intraluminal infiltration in the absence of a discrete mass [8, 11]. Biliary stricture and corresponding proximal dilatation help delineate longitudinal extension of tumor along the duct. Viewing of both axial and coronal reconstructions helps to visualize the anatomical relationships between the tumor and vascular structures. Extension of a stricture to secondary biliary ducts in a contralateral lobe is a contraindication to resection.

1.2 Bismuth–Corlette Classification

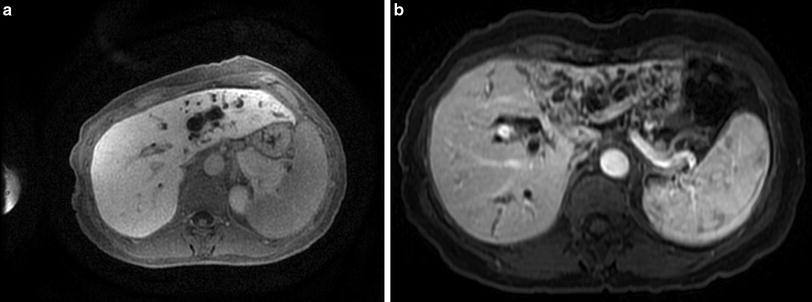

Patients with Bismuth–Corlette IIIa and IIIb cholangiocarcinoma are best treated with right or left hepatectomy (respectively), radical common bile duct resection, hepatoduodenal ligament lymphadenectomy, and bilio-enteric reconstruction. Preoperative cross-sectional imaging is necessary to confirm patency of the main and contralateral branch of the hepatic artery and patency of the main and contralateral branch of the portal vein. Ipsilateral portal vein impingement or occlusion, or involvement of ipsilateral hepatic artery does not preclude resection. A hallmark feature of locally advanced resectable hilar cholangiocarcinoma is lobar atrophy. It is associated with ipsilateral portal vein involvement and/or complete biliary obstruction [15, 16] and usually develops over time (Fig. 4a, b). While lobar atrophy has been associated with worse overall survival among patients with resectable hilar cholangiocarcinoma, it does not preclude a margin-negative resection [15, 17].

Fig. 4

Type IIIB hilar cholangiocarcinoma with significant intrahepatic ductal dilatation of the left ductal system (Panel a). With time, biliary and/or vascular obstruction leads to development of lobar atrophy (Panel b)

Patients with Bismuth–Corlette IV cholangiocarcinoma (Fig. 5) and those with contralateral vascular involvement are unresectable and should be evaluated for liver transplantation. Vascular encasement of the hepatic artery and/or portal vein and their branches is not a contraindication to liver transplantation. Liver transplantation is also a primary treatment option for cholangiocarcinoma in patients with PSC (Fig. 6a, b). PSC is an idiopathic chronic cholestatic liver disease with manifestations of progressive inflammatory destruction and biliary fibrosis of the entire bile duct system [18, 19]. These patients often have parenchymal disease precluding resection. Seven to 15 % of patients with PSC develop cholangiocarcinoma during their lifetime. The diagnoses of cholangiocarcinoma and PSC may be established at the same time, or cholangiocarcinoma may develop at a later time in patients with PSC. These patients are considered to have a “field defect” and are probably best treated by neoadjuvant therapy and liver transplantation rather than resection, even if they have otherwise potentially resectable tumors.

Fig. 5

Large Type IV hilar cholangiocarcinoma (arrow) obstructing biliary drainage from both right and left ductal systems with bilateral ductal dilatation. Tumor extends to secondary ducts in both right and left hepatic lobes

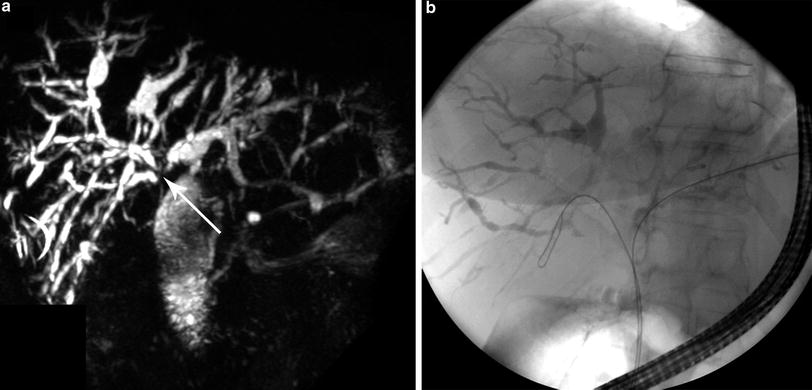

Fig. 6

MRCP demonstrating a Type IV cholangiocarcinoma (arrow) in a patient with PSC with multifocal intrahepatic strictures and dilatations (Panel a). A corresponding ERCP demonstrates classic beading of the intrahepatic bile ducts (Panel b)

2 Evaluation for Transplantation

2.1 Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria for Liver Transplantation

Patients with unresectable hilar cholangiocarcinoma or hilar cholangiocarcinoma arising in the setting of PSC should be evaluated for liver transplantation. Transplantation and resection are mutually exclusive therapeutic pathways, without possibility for cross over. Patients found to have unresectable disease during exploration for resection do not do well with subsequent neoadjuvant therapy and liver transplantation. In our experience, operative exploration and subsequent neoadjuvant therapy increases the technical difficulty with transplantation and increased the likelihood for recurrence after transplantation.

Patients who undergo pathologic confirmation of tumor by transperitoneal tumor biopsy or fine-needle aspiration (including endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-directed aspiration of the tumor) should also be excluded from transplantation [20].

Conversely, patients who fall out of the neoadjuvant therapy transplantation protocol cannot undergo liver resection even if they were thought to have potentially resectable disease. Neoadjuvant therapy causes widespread hilar biliary necrosis that would make resection and subsequent biliary reconstruction hazardous.

The United Network for Organ Sharing/Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (UNOS/OPTN) approved a model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) exception score in 2009 for patients enrolled in an approved neoadjuvant therapy protocol. The MELD score exception is similar to the exception model for patients with transplantable hepatocellular carcinoma [21, 22]. Neoadjuvant therapy and staging are critical to success [22–24]. Since histological and/or cytological confirmation of diagnosis is not always possible, diagnosis is often dependent on imaging. Definitive diagnosis for treatment requires presence of a malignant-appearing stricture and at least one of the following: (1) endoluminal biopsy or cytology positive for cholangiocarcinoma; (2) polysomy by fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH); (3) mass lesion on cross-sectional imaging at the location of the malignant-appearing stricture; or (4) CA 19-9 >100.

EUS with fine-needle aspiration (FNA) of suspicious nodes is useful to rule out patients with regional lymph node involvement destined to fall out at operative staging. Neoadjuvant therapy is associated with a multitude of side effects and potentially lethal complications and should not be administered unless the patient is a candidate for transplantation. It is important to make sure that aspiration is only done on the regional nodes and not on the primary tumor since that will preclude transplantation. Nodal metastases in any location—hepatoduodenal ligament (N1) or celiac, aortocaval, or retropancreatic (N2) lymph node basins—are a contraindication to neoadjuvant therapy and transplantation. Cross-sectional imaging of the abdomen and chest is also necessary to rule out extrahepatic metastases. Approximately 25–35 % of patients evaluated for neoadjuvant therapy are not amenable to treatment due to distant or nodal metastases.

Patients with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, distal cholangiocarcinoma (below the level of the cystic duct), and gallbladder cancer are best treated by resection. Even if tumors in these locations are unresectable, neoadjuvant therapy and transplantation have not been shown to have any efficacy. Other exclusion criteria include the following: primary tumor greater than 3 cm in radial diameter (perpendicular to the duct); uncontrolled infection; prior treatment with radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy that would preclude full-dose neoadjuvant therapy; and history of other malignancy within 5 years [23, 24]. Patients must also be a suitable candidate for transplantation.

Operative staging is essential prior to transplantation. When possible, operative staging is done by hand-assisted laparoscopy. It is best done prior to the actual transplant procedure to rule out locally extensive disease and presence of nodal, peritoneal, and extrahepatic metastases. Operative staging involves a thorough intra-abdominal exploration and biopsy of any suspicious lesions, a common hepatic artery lymph node overlying the hepatic artery at the takeoff of the gastroduodenal artery, and a pericholedochal lymph node. Occasionally, patients are too sick to undergo a separate operation, and staging is done at the time a donor liver becomes available.

2.2 Pre-Transplant Imaging

Pre-transplant cross-sectional imaging is performed every 3 months prior to transplantation as required by UNOS/OPTN policy for continuous surveillance of patients with malignancy awaiting liver transplantation. Evidence of disease progression or metastases while on the neoadjuvant protocol precludes transplantation. The patient dropout rate after starting neoadjuvant therapy is approximately 11.5 % per 3 months. Recurrent cholangitis occurs in the majority of the patients during neoadjuvant therapy [22

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree