Clinical Presentation

The patient is a 21-year-old male who presented with pain in the right lower lumbar spine. Over the past several weeks, the patient has noticed a sharp, focal pain in the right lower spine and hip. It is painful to the touch. The pain is worse at night and will occasionally awaken him from his sleep. His pain increases with activity. He notes that his pain goes away for several hours after he takes aspirin. A neurologic examination was normal.

Imaging Presentation

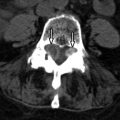

Axial and reformatted coronal computed tomography (CT) images reveal a large low-density mass containing calcification in the left posterolateral epidural space with irregularity and sclerosis of the left neural arch. The thecal sac is displaced anteriorly and to the left ( Fig. 54-1 ) . Surgical curettage revealed the mass to be an osteoblastoma.

Discussion

Osteoid osteoma (OO) and osteoblastoma (OB) are benign osseous lesions of osteoblastic origin, consisting of a hypervascular nidus and surrounding sclerotic bone. Osteoid osteoma was first described by Jaffe in 1935. Osteoblastoma was later described by Licchtenstein in 1956.

Both osteoid osteoma and osteoblastoma are most commonly found in the long bones. The spine is the location of osteoid osteoma in 10% of cases and of osteoblastoma in 35% of cases. Osteoid osteoma is usually seen in patients in their second decade of life, whereas osteoblastoma is seen in patients who are slightly older. Approximately 90% of osteoid osteomas and osteoblastomas occur before the age of 30. Both lesions are seen more commonly in males with ratios of 2 to 4:1.

Histologically, osteoid osteoma and osteoblastoma are similar, consisting of an osteoid nidus surrounded by sclerotic bone. Some clinicians believe that they are histologically indistinguishable and that their names should be changed to reflect that they are just different clinical expressions of the same process. They have remained distinct entities likely because of their different radiographic appearances and because they have different natural histories—osteoid osteoma tending to regress over time and osteoblastoma having the ability to progress and even transform into a malignancy. Radiographically, osteoid osteomas are more sclerotic, nonexpansive, and painful earlier in their development as opposed to osteoblastoma that tends to be less sclerotic and more expansile. McLeod and colleagues used a cutoff of 1.5 cm to distinguish osteoid osteoma from osteoblastoma. A nidus of less than 1.5 cm in diameter is considered an osteoid osteoma, and those greater than 1.5 cm are osteoblastomas, a classification that has remained widely used. Osteoblastoma of the spine will frequently invade the epidural space, surround nerve roots, and possibly cause cord compression. The incidence of epidural invasion by osteoblastoma is approximately 50%.

Osteoid osteomas and osteoblastomas have similar clinical symptomatology when they occur in the spine. The typical clinical symptoms are pain or varying intensity that increases with activity and often localizes at or near the site of the lesion. The pain may be more apparent at night and may awaken the patient from sleep. The pain is often reduced or may disappear altogether with the use of aspirin or other anti-inflammatory medications, although aspirin therapy is less effective with osteoblastoma. Clinically, lesions in the spine can have radicular features; however, neurologic examination is often normal. The incidence of neurologic deficits is significantly higher in patients with osteoblastoma than in those with osteoid osteoma.

Osteoid osteoma is the most common cause of painful scoliosis in adolescents, with all other causes of painful scoliosis being rare. One half of patients with osteoid osteoma in the cervical spine have scoliosis, and over one half of patients with osteoblastoma anywhere in the spine have scoliosis. It is important to consider the duration of a patient’s osteoid osteoma or osteoblastoma-related scoliosis and also the patient’s age because it appears that there is a critical amount of time that a patient with scoliosis related to osteoid osteoma or osteoblastoma has before it precludes resolution of the deformity. A study by Pettine and colleagues suggests that 15 months is the critical duration of symptoms if antalgic scoliosis is to undergo spontaneous correction after excision of the tumor. Patients with symptoms of less than 15 months duration had a decrease or complete correction of their scoliosis, and those with symptoms greater than 15 months did not. Furthermore, patients who were older when they had the onset of symptoms or those that were younger at the time of surgical excision had more spontaneous resolution of scoliosis.

If complete resection of osteoid osteoma or osteoblastoma is not achieved, there is a significant potential for recurrence. Osteoblastoma has a recurrence rate of 10% to 15% with incomplete resection and has a potential for sarcomatous transformation and metastasizing. Osteoid osteoma has a 4.5% recurrence rate and no potential for malignant transformation.

Imaging Features

Osteoid Osteoma

The nidus of an osteoid osteoma is the most important part of the neoplasm to visualize. Plain radiography is not the imaging method of choice to evaluate for a radiolucent nidus because of the overlapping anatomy of the spine. Reactive sclerosis can be visualized; however, this is not specific for osteoid osteoma. Technetium bone scans are very sensitive, but not specific for osteoid osteoma ( Fig. 54-2 ) . These observations have been reported by Swee and colleagues in which 75% of patients with osteoid osteoma on plain film radiographs had positive bone scans, and the 25% with radiographically negative/CT positive osteoid osteoma had positive bone scans. There have been no cases in the literature with a false-negative bone scan with proved osteoid osteoma. A nuclear medicine bone scan can be obtained to search for an intense focus of radiotracer uptake that would make one suspect osteoid osteoma; however, CT is regarded as the preferred imaging modality to localize the nidus for diagnosis, for presurgical evaluation for open procedures, and for localization purposes for percutaneous procedures. With CT, the nidus of an osteoid osteoma is usually of low attenuation with central mineralization and a varying degree of perinidal sclerosis ( Fig. 54-3 ) . The imaging characteristics with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are variable. The typical nidus is of low to intermediate T1 signal intensity and variable T2 signal depending on the vascularity of the osteoma and/or presence of central mineralization. The nidus demonstrates rapid, avid contrast enhancement. The zone of sclerosis surrounding the nidus usually demonstrates increased T2 signal intensity and will enhance, although it enhances slower than the nidus. Inflammatory enhancement can be seen in the soft tissues adjacent to the osteoid ostoma ( Fig. 54-4 ) . Dynamic contrast-enhanced MR is often used to separate nidus from the surrounding reactive zone.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree