Ovarian Vein Thrombosis

Puerperal ovarian vein thrombosis (POVT) is an uncommon but potentially fatal complication of postpartum endometritis, obstetric (e.g., cesarean section, endouterin manipulations) and nonobstetric gynecologic surgery, laborious delivery, pelvic inflammatory disease, tuboovarian abscess, and septic abortion.1–4 Originally described as a pathologic entity by Vineberg in 1909, the first symptomatic description was not described until nearly 50 years later by Austin in 1956.5 In 80% to 90% of cases, POVT affects the right ovarian vein. The postpartum related incidence has been reported to range from 0.02 to 0.18%, or one in 600 to 2000 deliveries.6–9 The cornerstone of diagnosis is based on noninvasive radiologic imaging. Treatment consists primarily of antibiotic and anticoagulant therapy. Thrombolytic therapy and (temporary) inferior vena cava filter placement may be considered as adjunctive treatment methods. The details of these issues will he dismissed.

Pathogenesis

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of POVT is intimately related to Virchow’s triad, which includes (1) changes in circulating coagulation factors; (2) disruption, damage, or changes to the vein wall endothelium; and (3) stasis in blood flow. Pregnancy, the postpartum state, pelvic inflammatory conditions, and many of the other described etiologies of POVT clearly satisfy Virchow’s proposed criteria for venous thrombosis. Pregnancy and the postpartum state are associated with increased circulating levels of coagulation factors I, II, VII, IX, and X.1,10 High thromboplastin levels in the placenta and amniotic fluid also can gain access to the mother’s circulation during delivery of the fetus and/or placenta, further accentuating the predelivery hypercoagulable state. Alterations in the vein wall itself can occur secondary to the effects of an elevated estrogen level, surgical trauma, trauma secondary to the delivery process (assisted or unassisted) itself, and microorganism-induced insults to the endothelium.1 Cultures of ovarian vein thrombus have yielded anaerobic streptococci, Proteus species, and yeast organisms.7 Chlamydia and mycoplasma also have been reported as risk factors for early postpartum endometritis.11 Stasis of blood flow, the third leg of Virchow’s triad, also is seen in the postpartum state. At term, the ovarian vein is approximately three times its normal size with a blood flow volume of about 60 times normal. At delivery, the venous velocity decreases sharply in the ovarian veins, resulting in a state of relative flow stasis and partial venous collapse.1 In addition, the normal dextrorotation of the enlarging uterus is believed to cause compression of the right ovarian vein (and right ureter), accentuating stasis. Further, in the immediate postpartum state, flow in the right ovarian vein is thought to be antegrade, whereas flow in the left ovarian vein is retrograde. This flow phenomena can increase the inoculum of infecting organisms further to the right ovarian vein.6,7 The right ovarian vein is also longer than the left and commonly contains multiple incompetent valves. These, as in lower extremities, can act as a nidus for clot formation and propagation.

Clinical Presentation

Clinical Presentation

Patients typically present 1 to 13 days postpartum or postoperatively with mild to moderate elevations of temperature, crampy right lower-quadrant abdominal pain extending to the pelvis or flank (left-sided symptoms with left POVT), chills, tachycardia, nausea, and vomiting 10,12,13 Clinical examination commonly demonstrates painful right adnexa. A palpable right (or left) periuterine chord or mass may be demonstrable.

Diagnostic Imaging

Diagnostic Imaging

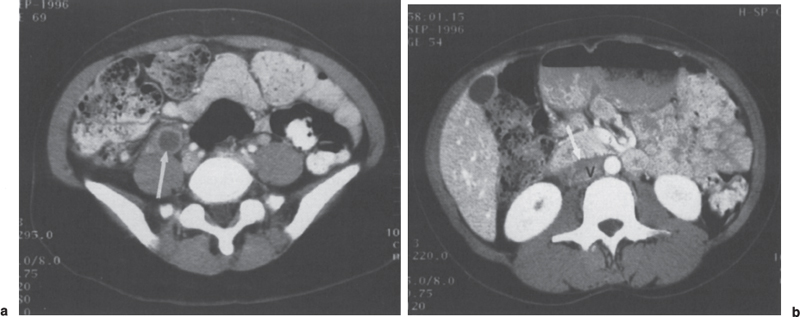

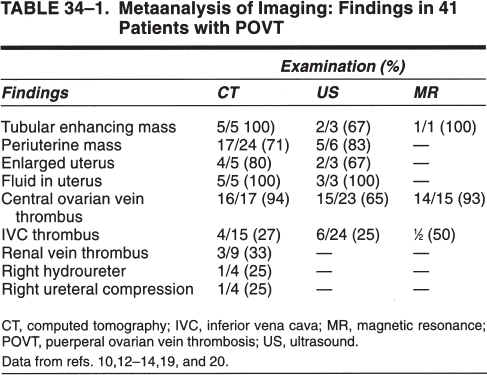

The diagnosis of POVT is established through the noninvasive imaging demonstration of one or more findings compatible with the working diagnosis. These findings include (1) tubular enhancing retroperitoneal mass (Fig. 34–1), (2) central ovarian vein thrombus (Figs. 34–1, 34–2, and 34–3) (3) periuterine mass (Fig. 34–2), (4) enlarged uterus, (5) fluid-filled uterus (Fig. 34–2), (6) inferior vena cava thrombus, (7) renal vein thrombus, (8) hydroureter, and (9) ureteral compression (Fig. 34–2B). Table 34–1 shows the incidence of these findings based on a metanalysis of six articles resulting in a group of 41 patients.

Computed tomography of the pelvis is well suited for the demonstration of the enlarged, fluid filled post-partum uterus and right periuterine mass that is commonly seen. The single most important finding, that is, a low-density solid tubular mass (thrombus) within the enlarged enhancing ovarian vein, is also well demonstrated and was seen in 16 of 17 (94%) patients (see Table 34–1). Secondary findings, such as thrombus extension into the inferior vena cava or renal vein, if present, also can be demonstrated by this modality. POVT may be associated with inflammatory retroperitoneal conditions such as an abscess (Fig. 34–4) or pelvic malignancies, including rectal carcinoma (Fig. 34–5). Helical computed tomography with bolus contrast injection can further improve the diagnostic accuracy of this technique.

FIGURE 34–1. Female with right-sided puerperal ovarian vein thrombus, (a) A dilated, thrombus-filled right ovarian vein (arrow) is identified at the level of the pelvic brim by axial computed tomography, (b) Image at the level of the kidneys demonstrates thrombus (arrow) extending superiorly to the junction of the ovarian vein with the inferior vena cava (V).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree