Ovarian Neoplasms

Ovarian tumors are composed of a wide variety of types. Although they are not the most common gynecologic malignancy, they cause more deaths than any other primary gynecologic tumor because they are so often asymptomatic until they have reached an incurable stage, and because widespread effective screening has yet to be developed.

There are several groups of primary ovarian tumor types; in descending order of frequency, these are epithelial tumors, germcell tumors, sex cord-stroma tumors, and gonadoblastoma. Other malignancies may metastasize to the ovary as well.

Among the epithelial tumors, serous cystadenomas and cystadenocarcinomas are relatively common, as are mucinous cystadenomas, cystadenocarcinomas, and endometrioid tumors. In this group, the majority are benign; a smaller proportion are of borderline malignancy, and a yet smaller fraction are clearly malignant. Brenner tumors and clear-cell epithelial cell tumors are seen less often.

Germ-cell tumors are composed of dermoid tumors or benign cystic teratomas. They contain a combination of endo-, meso- and ectodermal tissues, including teeth, hair, and oily, sebaceous, or fatty material and neural tissue. Malignant teratomas are less common, and squamous-cell carcinoma is even rarer. Dysgerminomas are an uncommon variety of germ-cell tumor. Yolk sac, or endodermal sinus, tumors are also rare, as are choriocarcinomas. Ovarian tumors encountered in children are most likely to be germ-cell tumors.

The least frequently encountered group of primary ovarian tumors are the sex cord-stroma tumors, types of which include the fibroma-thecoma, granulosa-cell tumor, and Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor.

Extraovarian malignancies may metastasize to the uterus. Breast carcinoma and lung carcinoma may do so, as may adenocarcinoma of the stomach or colon. The term Krukenberg tumor originally was applied to metastases that consisted of epithelial tissue with a specific signet-ring appearance of individual cells; the term is now sometimes used to denote any tumor metastatic to the ovary. Primary epithelial carcinomas of one ovary frequently appear on the contralateral one as well.

Many primary ovarian tumors remain asymptomatic for a lengthy period. Local symptoms from mass effect may occur; abdominal swelling or bloating or a sensation of pelvic fullness may be reported, or the tumor itself may be palpated. Uncommonly, dyspareunia is encountered; large masses may produce pain. Symptoms caused by ascites or pleural effusions may occur in late-stage cancer. Ovarian tumors may undergo torsion and cause severe pelvic or lower abdominal pain. Late-stage tumors may cause bowel obstruction. Meigs syndrome, which is classically described but infrequently encountered, includes ascites and a right pleural effusion, which accompany an ovarian fibroma.

Some tumors secrete hormones and other substances that help establish the diagnosis. Estrogen may be secreted by granulosa-cell and theca-cell tumors, which leads to precocious puberty in girls, or signs of postmenopausal bleeding in older women; these tumors have even produced virilization. There may be effects of estrogen on target tissues, including postmenopausal endometrial hyperplasia, endometrial carcinoma, or changes in the glandular tissue of the breasts. Sertoli-Leydig cell tumors may lead to virilization as a result of production of testosterone. Tumors may also secrete detectable substances that are clues to their diagnosis or to their posttherapy recurrence. These include CA-125, which is elevated in

about four-fifths of patients with epithelial ovarian malignancies; human chorionic gonadotropin, which can be secreted by choriocarcinoma and embryonal cell carcinoma; and elevated levels of alpha-fetoprotein, which may be secreted by embryonal cell and endodermal sinus tumors.

Mucinous adenocarcinomas of the ovary, like certain mucinous tumors elsewhere in the abdomen, may spread throughout the peritoneal cavity, so that widespread mucin production fills the peritoneal cavity with a jelly-like substance. This condition is called pseudomyxoma peritonei and may produce abdominal enlargement, bloating, pain, and even bowel obstruction.

The biology of the tumors has frustrated the development of screening measures; tests that are sufficiently accurate and inexpensive have been hard to find. To date, attention has focused on screening ultrasound and determinations of serum CA-125. Ultrasound is not inexpensive, especially when combined with transvaginal examination and reveals many ovarian space-occupying lesions that ultimately are shown to be benign. CA-125 is elevated in most epithelial ovarian cancers but is also increased in other cancers, including those of breast, colon, and pancreatic origin. CA-125 may also be elevated as a result of nonneoplastic disease, which in turn may be gynecologic (endometriosis, adenomyosis, fibroids), nongynecologic (cirrhosis, diverticulitis), and even physiologic (pregnancy). These factors make general screening ineffective. To date, there is no strongly supported indication that there is a subset of patients for whom screening might be worthwhile. Having first-degree or second-degree relatives with the disease increases the risk, as does nulliparity. Carcinoma of the breast doubles the risk of acquiring ovarian cancer, and a family history of endometriosis or some colon tumors increases the risk. Possessing the BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene confers particularly high risk. Investigation continues to determine whether screening may be worthwhile in high-risk groups. If screening is performed, a combination of CA-125 and ultrasound (preferably transvaginal) should be performed. If both are abnormal, the chances that the affected patient has ovarian carcinoma are markedly elevated; elevated CA-125 in the face of normal ovarian morphology does not seem to increase the likelihood of having ovarian cancer. Although preliminary data suggest that life expectancy may be improved by a carefully tailored screening program, a reliable conclusion is not yet possible; even cancers detected by screening are often advanced.

Staging of ovarian cancer is crucial, both for prognosis and treatment. The currently used system is that adopted by FIGO: the staging system (

Table 18.1) depends primarily on initial operative, rather than imaging, findings.

Initial treatment of ovarian cancer nearly always is surgical. Usually, the patient has a total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingoophorectomy. Only in very rare circumstances, in which there is a small tumor clearly limited to one ovary, the uterus and other ovary may be left to permit fertility. Surgery includes widespread abdominal and pelvic exploration to seek peritoneal implants and peritoneal washing to search for exfoliated cells from metastases. If there is extensive abdominal disease, a debulking procedure is performed in which as much tumor is removed as possible.

Except for the most localized of disease, the majority of patients receive postoperative chemotherapy. At an interval after chemotherapy, a “second-look” laparotomy is sometimes performed for disease assessment, but PET-CT and CA-125 follow-up studies have rendered the utility of this operation questionable.

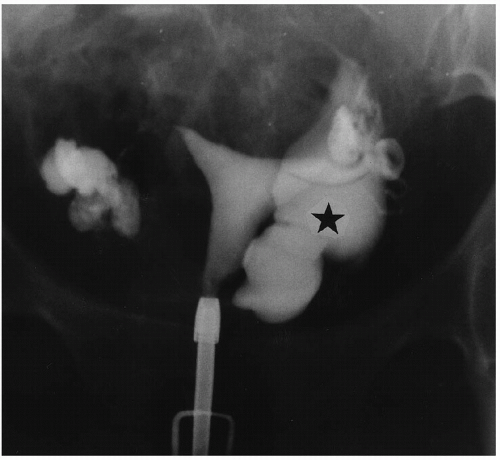

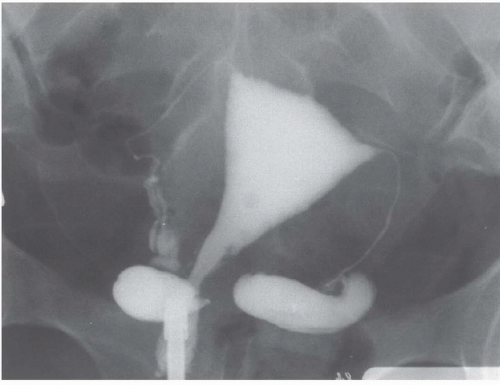

Radiography and urography are not used deliberately to detect ovarian cysts, although large benign or malignant cysts may be directly visible as pelvic masses, and ascites may be detectable. Any pelvic space-occupying lesion, if sufficiently large, may cause ureteral obstruction. Occasionally, small bowel or barium enema examinations reveal metastatic ovarian carcinoma as mural masses in the gut; enteric metastatic disease occasionally produces bowel obstruction.

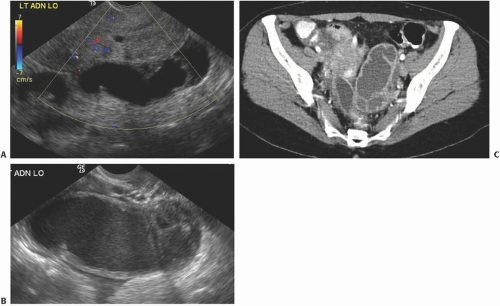

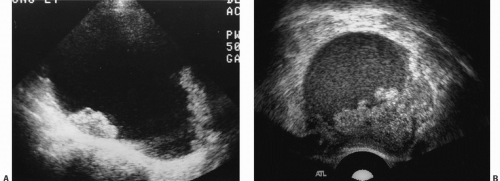

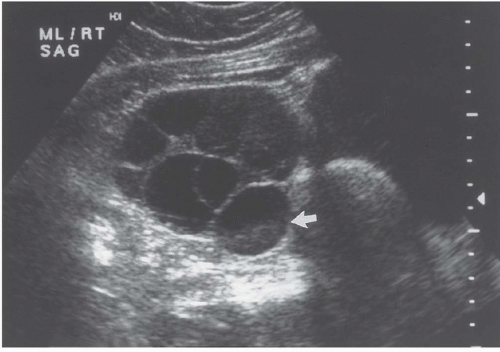

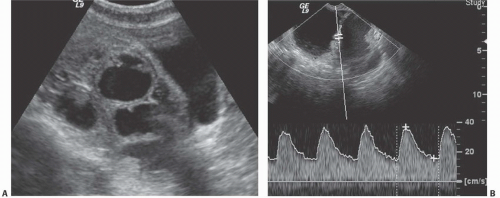

Ultrasound is the primary imaging modality for the detection of cystic ovarian lesions, although CT and MRI can demonstrate them as well. Cystadenomas have ultrasound characteristics similar to those of simple cysts elsewhere in the body. The fluid is usually anechoic and produces enhanced through-transmission; occasionally, hemorrhage or other debris may appear as low-level echoes in the dependent portion (

Fig. 18.8). The lesions are circular or ovoid and the wall is thin; in cystadenomas, regions of solid tissue should not be detectable. Cystadenomas occasionally have septi, but they

are few and thin. Calcification is unusual. Demonstration of clearly normal ovarian tissue at the margin of a cystic mass strongly suggests that the mass is not malignant.

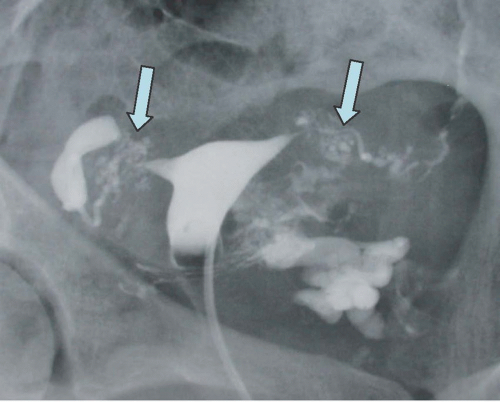

Cystadenocarcinomas tend to have regions of viable solid tissue (

Fig. 18.9); this may appear as regions of thickening in the wall or thick septi (which may be more numerous than those seen in cystadenomas) or as papillary nodules within the wall or projecting into the cystic region. Occasionally, adenocarcinomas may consist primarily of solid perfused tissue and have only small cystic regions within them. The fluid within mucinous cystadenocarcinomas tends to have more echoes within it than the fluid in serous cystadenocarcinomas.

Doppler ultrasound contributes a great deal of information that is of value in distinguishing benign from malignant cystic lesions. Color and power Doppler images tend to show more flow in malignant tissue. The pulsatility index or the resistive index often shows low-impedance flow through the solid tissue. Various authors have suggested different thresholds of these indices for distinguishing benign from malignant lesions. Malignant tumors are much more likely to have Doppler-detectable flow in central regions, whereas both benign and malignant lesions may demonstrate peripheral flow. Doppler indices are far from perfect in distinguishing benign from malignant lesions, however. Even nonneoplastic vessels whose muscular walls are dilated will produce relatively low pulsatility and resistive indices, so that the inflammatory tissue in the margins of some tubo-ovarian or other abscesses may mimic the Doppler pattern of malignancy, as may flow in the margins of rapidly changing or hemorrhagic corpus luteum cysts or even in some dermoids.

In widespread intra-abdominal disease, ultrasound may also provide valuable information. Ascites is frequently demonstrable, as are cystic masses of the serosal surfaces of the gut, omentum, or upper abdominal viscera; occasionally, enlarged pelvic lymph nodes or hepatic metastases may be demonstrable as well. In patients in whom widespread mucinous adenocarcinoma has caused pseudomyxoma peritonei, ultrasound may reveal a large amount of intraperitoneal material, which is of low echogenicity and avascular. No technique is very sensitive, either initially or after therapy, for small peritoneal implants.

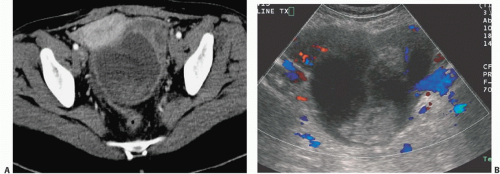

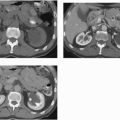

CT of ovarian cystadenomas reveals findings similar to the ultrasound features. The lesions are usually of water density although they may be denser because of hemorrhage, and their central portions do not enhance. The walls are very thin and enhancement of them may be minimal (

Fig. 18.10). They are ovoid or spherical, and contain no internal papillary projections or vegetations and no enhancing solid components. There may be curvilinear calcification in the wall. There is no size threshold that clearly separates cystadenomas from cystadenocarcinomas, but malignant tumors tend to be larger than benign ones. Lesions smaller than 5 cm in diameter and that have no thick-wall segments or solid components are very likely to be benign.

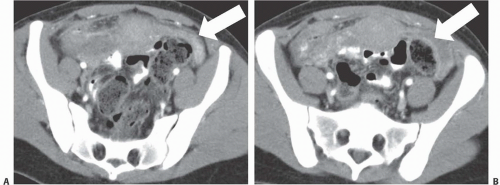

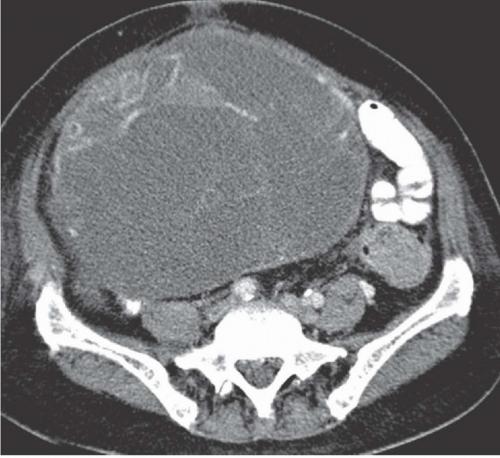

Cystadenocarcinoma produces CT findings qualitatively similar to the ultrasound ones. The walls of the cystic portions may be thicker, either focally or circumferentially, and the central portions of the tumor may contain solid enhancing nodular regions (

Fig. 18.11); occasionally, the solid tissue will predominate, or the tumor may even be completely without cystic areas. When seen on CT, the tumors usually are larger than 5 cm in diameter and may reach a huge size, becoming more than 20 cm in diameter. The solid portions may calcify.

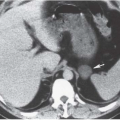

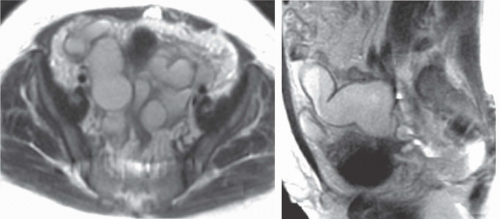

Intra-abdominal metastatic disease has various patterns (

Figs. 18.12 and

18.13). Tumor nodules may be seen on the parietal peritoneum or on the serosal surface of any portion of the gut or on the surface of the liver or spleen. Lymph node enlargement suggests involvement with metastatic disease; the first nodes to enlarge may be at the level of the renal hilus rather than in the pelvis. More widespread intraperitoneal metastases may be demonstrated by generalized thickening and infiltration of the omental fat (omental “caking”) or as extensive areas of heterogeneous solid tissue anywhere in the peritoneal cavity. Focal metastatic lesions of the liver or spleen are usually late manifestations and nearly always appear on the surfaces of the organs rather than entirely within the parenchyma; they are usually cystic with solid components and enhancing rims. Metastases may calcify. Ascites is frequently seen with disseminated disease, and pleural effusions may occur as well. Lung metastases appear late.

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access