Chapter 27 Paediatric imaging in general radiography

Introduction

Radiographers are encouraged to formulate collaborative approaches through interprofessional working with other healthcare professionals and contact with colleagues at dedicated paediatric units throughout the country. The Association of Paediatric Radiographers (APR) is an excellent initial contact.1 Not only will this be of direct benefit to patients but it will also contribute to the radiographer’s continuing professional development. The specialty of paediatric imaging provides potential scope for the introduction of advanced and consultant radiographer practitioners for those aspiring to a career in this area.

Special considerations when imaging children

The key factor in obtaining a high-quality diagnostic image is undoubtedly the gaining of the child’s trust prior to the commencement of the examination.2 With such trust follows the development of the patient–radiographer relationship that will result in compliance by the child and positive feelings about the imaging experience. Positive feelings are invaluable in the paediatric age group, as a large proportion of children are likely to return for X-rays in their formative years.

The Kennedy Report,3 in the context of heart surgery, advises that all children should be treated in a paediatric environment by paediatric specialists and healthcare professionals. Clearly this is unachievable in many general hospitals. It is likely that most will agree that radiology departments should have at the very least a named lead radiographer and a core team of staff that are specially trained, competent and keen to examine children.4 It is not unreasonable to strongly suggest that all undergraduate diagnostic radiography students should be provided with learning opportunities in dedicated paediatric departments. Most radiographers will examine children as early as their first appointment as a radiographer. Therefore, a sound knowledge and understanding of the paediatric specialty gained during placement will be of great benefit to all radiographers commencing their careers.

Anxiety is a common emotion in patients of any age, but is often heightened in children due to unfamiliar surroundings, adults, and sometimes the reactions of their parents/carers. The radiographer needs to appear friendly, positive and self-assured and able to instil a sense of confidence in both the child and the parent/carer (Fig. 27.1).

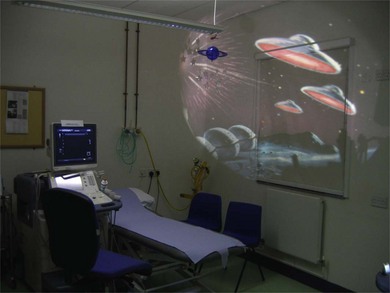

Ensuring that the physical environment is favourable to imaging children is an important factor, although this is often dependent upon additional funds and the backing of management. Child-friendly decor and furnishings with toys and books, ideally away from the adult waiting area, helps to achieve a welcoming, relaxed and warm atmosphere (Fig. 27.2).

• Enabling the child to make choices, such as selection of a lead gown for their parent/carer, will give them a degree of feeling in control over their surroundings.

• Allowing the child to bring a favourite toy or comforter into the examination room helps dispel fears. On occasions taking an X-ray of the toy can prove a worthwhile venture to help the child understand what the examination involves.

• Likening the patient’s position for the examination to a normal everyday occurrence can be extremely advantageous. For example, asking a child to breathe in as they would do to blow up a balloon or swim under water is likely to result in a better effort than the instruction to breathe in alone.

• Rewards, be it stickers or certificates, have proved to be excellent incentives, particularly for children likely to return for regular imaging. Many children look forward to receiving another sticker for their collection.

• Consideration should be given to ensure the child’s privacy and dignity are maintained throughout the examination. This applies to all examinations, and needs to be balanced alongside the requirement to obtain images of maximum diagnostic quality with no artefact, if avoidable, for example removal of nappies for abdominal and pelvic imaging.

Radiation protection and dose limitation

Radiation exposure in the first 10 years of life may have an attributable lifetime risk three to four times greater than that after 30 years of age.5 As such, there is a greater opportunity for potential harmful effects to manifest themselves. The rationale in this chapter is to offer suggestions for radiation dose reductions; however, optimisation of the exposure factors may be more realistic. The choice of radiographic exposures should be in accordance with the 1996 CEC guidelines,5 taking weight, age and size into account. For examinations conducted using the X-ray table or bucky, automatic exposure devices may be used. The radiographer needs to consider the size of the selected chamber in comparison with the child’s anatomical size. In these instances it is important that the correct ionisation chamber and X-ray tube potentials are selected. Information on exposure factors should be readily available throughout the department, including mobile apparatus. It is essential that there is close working alongside clinical scientists to ensure that the appropriate balance between dose and image quality are maintained. Although practitioners may become involved in the evaluation of computed/digital radiography systems, it is important that consideration is given to dose, particularly when used for imaging children.6 Added consideration may need to be given to the optimisation of paediatric doses in non-specialist centres where digital imaging is already in place.

In keeping with the Ionising Radiation (Medical Exposure) Regulations7 prior to carrying out a diagnostic radiographic examination, all requests must be clinically justified. It is not uncommon for junior clinicians to over-request X-rays on children through inexperience with image interpretation or difficulties encountered during the initial assessment. Radiographers need to fully understand the RCR guidelines8 and enlist the assistance of a radiologist colleague if necessary.

Radiographers will need to confirm the pregnancy status of any female of child-bearing age before undertaking a radiographic examination.7 The lower age limit for pregnancy status is considered to be 12 years; however, some girls commence menstruation as young as 10. The issue of ascertaining pregnancy status is complex and delicate. A simple and uncomplicated approach is recommended as one that is likely to achieve an honest answer. First, the radiographer should ask whether the patient has started her monthly periods. If the answer is confirmatory, the radiographer needs to ask whether there is any possibility that the patient could be pregnant. Ideally this conversation should take place away from the parent/carer, and make clear to the patient that it is an important part of the radiographer’s responsibility to ask such questions. Proof of pregnancy status should be retained permanently, either electronically or on paper.

A common error by radiographers who do not undertake X-ray examinations on children regularly is the failure to tightly collimate the primary beam. This may be through fear of missing the area of interest off the image. The use of effective immobilisation, be it with devices or a holder, coupled with ongoing learning and skill development, should enable the radiographer to feel confident about collimating more appropriately and thereby limiting radiation. A holder can be defined as anyone who supports and immobilises a patient during a radiographic exposure.2 Different centres may use varying approaches in their recommended choice or preference of holder, be it the child’s parent, carer or healthcare worker. Debate and appropriate recommendations on this subject should be encouraged, but the radiographer must be aware that immobilisation is a potentially contentious issue, in that there is a difference between immobilisation and restraint. It is therefore recommended that radiographers are fully conversant with the hospital’s holding policy.

The holder’s fingers should always be excluded from the primary beam. Should the fingers be close to the primary beam, lead gloves/mittens should always be worn, although they will not provide complete protection at higher beam energies (Fig. 27.3). It is recommended that records are kept of any radiographers or healthcare personnel who hold children for X-ray examinations to avoid the same individual regularly undertaking this role.1

Facilitating the radiographic examination

As previously mentioned, immobilisation or clinical holding is sometimes unavoidable to obtain diagnostic images in a safe and controlled manner. Most hospitals will have a patient restraint policy document, often called a ‘clinical holding policy’. It is important that a copy is kept in the radiology department. It is essential that all radiographers likely to be involved in immobilising children are adequately trained and aware of alternative approaches to gaining a child’s cooperation. This may include distraction techniques (Fig. 27.4), play therapy, improved explanations or simple persuasion. Non-cooperation may be due to the child having a bad day or sensing their parent/carer’s anxieties. On occasions having a break or time out can work wonders. Children who have undergone a seemingly endless series of examinations may benefit from returning on another day, provided this does not jeopardise their clinical management.

Samples of tried and tested techniques are as follows:

• Prepare the examination room with several sizes of image receptor (IR), immobilisation pads and sandbags, protective lead aprons.

• Employ methods to reduce the potential for cross-infection.

• Select a preliminary imaging exposure prior to inviting the child into the room.

• Introduce yourself to the child and their family using your first name. Make eye contact and smile. Asking who the child has brought with them today will make them feel important and also act as a means of establishing the identity of the adult without mistake or embarrassment!

• Upon entering the examination room, ask them how they are today, whether they have had an X-ray before. Encourage them to talk about it if they are happy to do so.

• Look for conversation topics such as birthdays, holidays, sports (particularly if a sports shirt is being worn), or favourite television programmes (characters are often featured on clothing).

• Demonstrating the position required is often more effective than a description. Enlisting the help of the parent/carer can be particularly beneficial.

• Consider a practice run to limit the need for a repeat examination, for example for chest X-rays to avoid over inflation of the lungs.

• The child watching the light and announcing when it has gone out has proved to be a useful game. The child feels important in being given a job and is likely to be more compliant.

• Encourage the child to count while the X-ray is being taken. This may assist in maintaining the correct position.

• Children requiring comfort and reassurance from their parent/carer are best examined close to these adults. Clinicians carrying out patient assessment and examinations on children undertake as many required tests as possible while the child is seated on the lap of their parent/carer.9 This approach works equally well with children in the X-ray room.

• If two projections are required and one is likely to be easier or less distressing than the other, it often pays to perform the easier one first.

Common mistakes and errors in paediatric radiographic examination

General errors that can occur during paediatric examinations, and the reasons for them, are detailed in Table 27.1. Common errors are also identified for some individual projections, when there may be additional considerations or common faults associated particularly with paediatric examinations; otherwise errors and their correction can be assumed to be the same as those for adults.

Table 27.1 Common errors noted in paediatric radiography

| Common errors | Possible causes |

|---|---|

| Too large an X-ray field size | Overestimation of a child’s anatomical proportions/area of interest |

| Insufficient demonstration of anatomical area | Incorrect centring points – using those appropriate for adults that may not be suitable for child examinations (e.g. chest radiography in neonates) |

| Images of the parent’s/holder’s hands, or other parts in the region of interest | Extremities in the primary beam due to immobilisation attempt – often due to insufficient communication from the radiographer |

| Movement unsharpness or some/all area under examination moved outside collimated field | Inadequate immobilisation technique used |

| Patient movement, crying, respiration, too long an exposure time | |

| Increased cardiac motion in babies for chest imaging | |

| Generator unable to support short exposure times. This may be more evident where mobile equipment is used | |

| Gonad or lead protection obscuring the area of interest | Misplacement of item by the radiographer |

| Movement of the child | |

| Movement of item by the parent has also been noted! | |

| Under- or overexposure of the resultant image through the use of an automatic exposure device | Similarly to adults, incorrect selection of the ionisation chamber |

| Movement of the child, removing required area away from ionisation chamber | |

| Additional radiographic artefacts | Clothing image artefact |

| Body piercing jewellery in situ | |

| Foam support pads/sandbags not radiolucent ‘comforters’ (e.g. dummy) |

Chest

The chest X-ray is one of the most commonly requested radiographic images in children but is often difficult to obtain and can be of poor quality, particularly in the younger age group.10

The posteroanterior (PA) erect projection is preferred by radiologists, although in practice the anteroposterior (AP) is more readily performed in infants and young children as they are more likely to cooperate with this style of examination. This patient preference can be attributed to the need of the child to see their surroundings and their parent/carer. Unfortunately, the choice of technique often relies heavily upon the confidence of the radiographer: the less capable individual may elect to use the AP projection when careful assessment and communication might have established that a PA could have been achievable. In other words, it may be more ‘convenient’ for the radiographer to undertake a supine AP projection in preference to an erect AP. It should be remembered that the majority of children reach their sitting milestone at approximately 6 months of age. The implication here is that at the very least erect projections should be performed from this age, or before.2

PA erect chest

The adult technique is appropriate for use in older children and reference should be made to Chapter 23.

AP erect chest

IR is vertical for this examination; size must be appropriate for the child

Positioning

• A stool is placed in front of the erect unit. A rubberoid material, e.g. Dycem, can be placed on the seat to prevent the child slipping

• The child is encouraged to sit on the stool with their back against the IR. The upper border of the receptor should be visible above the shoulders if a cassette-type IR is used

• A 15° radiolucent pad (if using digital radiography check the pad does not cause an artefact) may be placed behind the child’s back, in front of the receptor, to limit the degree of lordosis and to act as a soft cushion to protect the back of the head

• A Velcro band may be useful to assist in maintaining the optimum position

• Both arms should be flexed at the elbow and raised to the side of the head. where they may be supported by the child’s parent/carer or escort

Beam direction and focus receptor distance (FRD)

Horizontal, with a 5–10° caudal angle to reduce lordotic appearance on the image

Centring

For babies: in the midline between the sternal angle and the xiphisternum

For older children: use the same centring point as for adults

Supine AP

An appropriately sized cassette-type receptor is placed on the table or in the cot/bed/incubator. Incubator sides should be opened for the absolute minimum of time to avoid temperature changes, which can adversely affect the patient. Evidence suggests that neonates are also susceptible to noise and vibration, which should be kept to a minimum. Be aware that incubators need to be separated by a distance of at least 60 cm in order to reduce the cumulative scatter dose to neighbouring isolettes.11

• The child is placed on the receptor with the shoulders and head resting upon a 15° pad, to reduce lordosis and aid patient comfort

• If not detrimental to the child’s wellbeing, the arms should be extended, abducted anteriorly, raised and immobilised by the side of the head. Most efficient immobilisation is achieved by the arms held against the head by the elbows

• Some assistance may be required to avoid rotation of the child’s lower body

• When examining a child in an incubator, strips of lead rubber can be arranged to form a ‘window’, providing radiation protection to the child and holder while improving image quality

Centring

For babies: in the midline at the level of the sternal angle or nipples

For older children: use the same centring point as for adults

Criteria for assessing image quality

• Image is as free as possible from artefact

• Sharp visualisation of the heart and lungs

• Mandible and chin must not obscure the lung apices

• Adequate penetration (appropriate kVp) to demonstrate the retrocardiac area

• No evidence of rotation – scrutiny of rib symmetry

For general errors please refer to the introductory section of this chapter.

| Common errors | Possible causes |

|---|---|

| Lordotic image – anterior ribs appear horizontal or lie above the posterior ribs | Hyperextension of the child’s arms or |

| child has arched their back during exposure | |

| Left to right asymmetry of the anterior and posterior ribs | As for adults, rotation of the area – small children are far more ‘cylindrical’ in shape than older children and adults, making this fault more common |

| Soft tissue opacification over one or both of the apices | Neck is insufficiently extended, the soft tissues of the chin or mandible are overlying the area of interest. More frequently encountered in children than adults |

| Hyperinflated chest | Exposure has been made during a large intake of breath by the child during crying or over-enthusiasm |

| In cases of incubator baby images: circle overlying the image | ‘Porthole’ of incubator lid overlies the area of interest |

| Excessive amount of abdomen included on the chest image | Centring too low – often encountered in neonates |

| Spine appears curved/scoliotic | Slouched position |

| Vertical streaking artefact | Hair artefact |

Lateral chest

Positioning

• Where possible, children should be imaged erect, either standing or sitting, as for adults

• Very young children should be examined lying on their left side on the receptor with their head supported on a foam pad

• Infants being nursed in incubators may require a horizontal beam lateral while the receptor is safely supported vertically at one side

• Arms should be raised to either side of the head, away from the area of interest

• The neck needs to be adequately extended in order to prevent superimposition of the soft tissues of the chin or mandible upon the resultant image