Clinical Presentation

The patient is a 67-year-old man who presented with a chief complaint of low back pain that had been worsening over the last 2 years. The pain radiates down both legs and is worse with walking. He must sit down in order to gain relief. The patient also complains of midline upper thoracic spinal pain that has been occurring for the last month. The patient has a history of bladder cancer. Laboratory evaluation demonstrates elevated alkaline phosphatase.

Imaging Presentation

Sagittal and axial T1-weighted images demonstrate enlargement of the L5 vertebral body in its anterior-posterior dimension but not in height. On the sagittal image, the L5 vertebral body has a characteristic picture-frame appearance and loss of its typical trabecular pattern. These findings are characteristic of Paget disease of bone ( Fig. 58-1 ) .

Discussion

Paget disease (PD) is a chronic metabolically active bone disease, characterized by a disturbance in both bone modeling and remodeling secondary to increased osteoblastic and osteoclastic activity. PD of bone can be a monostotic (single bone) or polyostotic (multiple bones) nonhormonal disorder. PD was originally described by Sir John Paget in 1877.

PD, also known as osteitis deformans , is a common metabolically active bone disease, second only to osteoporosis. It is more common in people of Anglo-Saxon origin. Radiographic studies have revealed a prevalence of 3.5%. A recent study of radiographic examinations of the pelvis demonstrated an overall prevalence of 1% to 2% in the United States, with near equal distribution in whites and African Americans and between men and women. By the age of 90 years, the prevalence jumps to approximately 10%. Recent studies have demonstrated several interesting findings. First the incidence and prevalence of PD are declining. Second, the severity of the disease is decreasing as measured by serum alkaline phosphatase levels. Third, there has been a rise of the age at presentation by approximately 4 years per decade, and lastly, the proportion of patients with monostotic disease is increasing.

The etiology of PD remains debatable. Because Paget disease can undergo sarcomatous transformation (0.7% of cases, some believe that PD is a benign neoplasm of the mesenchymal osteoprogenitor cell. Others have postulated that PD is caused by a viral disease or a zoonosis associated with ownership of birds, dogs, cats, or cattle.

Paget disease most commonly involves the pelvis, with the spine being the second most common site. Hartman and Dohn demonstrated that approximately 15% of patients with PD, either monostotic or polyostotic, have vertebral involvement. Polyostotic PD is seen in 66% of cases with between 35% and 50% of the total having spine involvement. The L4 and L5 levels are the most frequently involved sites of spine involvement, closely followed by thoracic involvement. Cervical involvement is much less common.

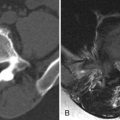

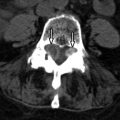

Spine involvement predisposes patients to low back pain and spinal stenosis. Back pain is the most common clinical symptom associated with PD of the spine. The back pain of PD can be due to the disease itself or its complications, including periosteal stretching, vascular engorgement, microfractures, facet arthritis, intervertebral disc disease, overt fractures, spondylolysis, spondylolisthesis, and sarcomatous transformation. The spine pain of PD is often a deep, dull ache that is unrelated to activity and not relieved by rest or anti-inflammatory medications. The most common complication in PD of the spine is a vertebral compression fracture, which manifests with an acute onset of back pain. Approximately one third of patients with spine involvement exhibit symptoms of clinical spinal stenosis. Spinal stenosis can be caused by three different methods: (1) posterior expansion of the vertebral body ( Fig. 58-2 ) , (2) expansion of the neural arch with overgrowth of the facet joints ( Fig. 58-3 ) , or (3) a combination of the two. The bone enlargement can cause classic symptoms of neurogenic claudication or if there is neural foraminal encroachment, radicular pain. Not all patients with spinal stenosis secondary to PD have clinical symptoms. Some patients with severe spinal stenosis may be asymptomatic, whereas some patients with mild spinal stenosis may have significant back pain.

Imaging Features

With spinal PD, the vertebral body is nearly always involved in conjunction with a portion of the neural arch. The radiologic appearance of PD is enlargement of vertebra characterized by enlargement in the anteroposterior and lateral dimensions but not in the overall height of the vertebral body (see Fig. 58-1 ). There are three phases of PD; an active/osteolytic phase, a mixed osteoblastic/osteolytic phase, and an inactive phase. PD is usually not discovered until the mixed phase in which there is a combination of trabecular bone hypertrophy and thickening at the endplates with apposition/absorption on the periosteal/endosteal surfaces at the anterior and posterior vertebral borders leading to the “picture-frame” appearance. At this stage, the vertebra has a squared appearance with a thickened cortex and loss of the anterior concave margin (see Fig. 58-1 ). As the process moves into a more sclerotic phase, one may see an “ivory vertebra” resulting from an increase in overall vertebral density. At this stage, one could mistake PD for a metastasis or primary neoplasm; however, the increased size of the vertebra is an important clue to the actual diagnosis. Occasionally, one may see PD in its early osteolytic phase with the appearance of a “ghost vertebra”.

Imaging with computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) depends upon the phase in which one discovers PD. In the lytic phase, there is loss of much of the trabecular pattern. On MRI, the marrow is hypointense on T1-weighted imaging and hyperintense on T2-weighted sequences secondary to the fibrovascular marrow. On CT, there is absence of the trabecular pattern ( Fig. 58-4 ) . In the mixed (blastic-lytic) phase, there is thickening of the cortex, enlargement of the vertebral body, and a coarsened, disorganized trabecular pattern with focal areas of fat density/intensity. This phase is often seen as combinations of hyperintensity and hypointensity on T1- and T2-weighted acquisitions ( Fig. 58-5 ) . The late phase is characterized by gradual decrease in both osteoclastic and osteoblastic activity, with residual smoldering osteoblastic activity. MR imaging in the late phase may demonstrate enlarged, thickened vertebra with decreased T1 and T2 signal intensity and sclerosis on CT ( Fig. 58-6 ) . Nuclear medicine bone scan will demonstrate increased radiotracer uptake in the pathologic vertebra in the active phase ( Fig. 58-7 ) , but may not demonstrate any abnormality in the inactive phase. Plain films are the most cost effective imaging tool to diagnose and follow PD. CT can be obtained if there is concern related to possible bone destruction. CT or MRI can be reserved to evaluate claudication and/or radicular symptoms. Nuclear medicine bone scan can be used to evaluate the overall extent of the disease process.