Pancreatic Trauma

Traumatic injury to the pancreas is rare and difficult to diagnose. The retroperitoneal location of the pancreas is a mixed anatomic blessing in patients with abdominal trauma. Its fixed position anterior to the vertebral column provides excellent protection against deceleration injury and posterior stab wounds. This protected environment, however, can be breached by bullets and more severe deceleration forces that may cause life-threatening pancreatic injury. Because of its rarity and nonspecific symptoms, the diagnosis of pancreatic injury is often delayed. The retroperitoneal location is detrimental to prompt diagnosis because signs and symptoms of pancreatic injury often evolve slowly and may be misleading. Delay in diagnosis and initiation of treatment in large part contributes to the potentially significant complications of pancreatic injury, including pseudocyst, abscess and fistula formation, sepsis, and chronic pancreatitis. There is considerable truth to the surgical aphorism that “the pancreas is not your friend” in terms of the unforgiving nature of pancreatic injuries. Because of the retroperitoneal location of the pancreas, pancreatic injuries are not easily diagnosed by diagnostic peritoneal lavage, which has a high false-negative rate. Furthermore, the classic presentation of upper abdominal pain, leukocytosis, and hyperamylasemia common in acute pancreatitis is far less reliable in the setting of pancreatic trauma. Multidetector computed tomography (MDCT), ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) can expedite the diagnosis and management of these patients.

Epidemiology and Pathophysiology

Pancreatic injuries are relatively rare, found in only 72 (0.4%) of more than 16,000 trauma patients. The pancreas is involved in only 2% of penetrating injuries and 5% to 12% of blunt abdominal injuries. The incidence of pancreatic trauma is increasing, however, because of the rising number of high-speed automobile injuries and gunshot wounds. Approximately three quarters of pancreatic injuries are due to penetrating trauma caused by gunshot or stab wounds. The remainder are secondary to blunt trauma caused by a sudden localized force to the upper abdomen as a result of a direct blow from a fall, a kick, or a steering wheel or bicycle handlebar injury. These forces compress the neck or body of the pancreas against the spine just to the left of the mesenteric vessels, causing crushing injury or transection. Blows to the left of midline may injure the pancreatic tail or distal body and may be associated with concurrent splenic, gastric, left renal, or descending colonic injury. Blows to the right of midline may injure the pancreatic head or uncinate process along with the bile ducts and may be associated with additional hepatic, duodenal, right renal, or ascending colonic injury.

Although pancreatic injuries are relatively infrequent, they have an overall mortality rate of 16% to 20%, which increases substantially when they are associated with other abdominal injuries. The mortality rate is independent of the mechanism or grade of injury. The mortality rates vary on the basis of the location of pancreatic injury, with rates of 22%, 18%, and 10% for the head, body, and tail, respectively. Approximately 90% of patients with pancreatic damage have concomitant visceral injuries because of the intimate relationship between the pancreas and the duodenum, biliary tract, colon, spleen, stomach, and major systemic and splanchnic blood vessels. Indeed, there are an average of 3.5 associated intra-abdominal injuries in patients with pancreatic trauma. In patients with combined pancreatic and duodenal injuries, the mortality rates are 5% for stab wounds, 15% for blunt injuries, 20% for gunshot wounds, and more than 50% for shotgun wounds. Most of the deaths occur within the first 48 hours of injury and are due to hypovolemic shock and major hemorrhage that result from vascular injury. The main source of delayed morbidity and mortality is disruption of the pancreatic duct, as isolated pancreatic injuries that spare the pancreatic duct rarely result in a poor outcome. Multiple organ failure and infection account for the remaining deaths. One third of survivors have major complications, such as chronic pancreatitis, pancreatic fistula, pseudocyst, pancreatic abscess, delayed massive hemorrhage, focal necrosis, hypocalcemic tetany, diabetes, and steatorrhea. Fistula formation after pancreatic trauma is seen in 7% to 20%. A delay in diagnosis is a major contributing factor to the high morbidity and mortality associated with pancreatic injury. Although the need for surgical exploration is obvious in patients with penetrating trauma, pancreatic injury may be clinically occult, and a high index of suspicion must be maintained. With the current emphasis on nonoperative management of blunt trauma with established solid organ injuries, the risk of missed pancreatic injury becomes even more important.

Rarely, the pancreas is injured during CT- or ultrasound-guided pancreatic biopsy, leading to pancreatitis or major hemorrhage. Even more uncommon is the possibility of pancreatic injury during laparoscopic urologic surgery, with an incidence of 0.44%, exclusively reported in left-sided procedures.

Clinical Findings

The classic clinical triad of acute pancreatic trauma of upper abdominal pain, leukocytosis, and hyperamylasemia is of limited value in the diagnosis of pancreatic injury. The serum amylase level is often elevated in patients with pancreatic trauma, but it may initially be normal in a large percentage of patients, especially if it is obtained within 3 hours of trauma. Elevated serum amylase and lipase levels may be seen in only 73% to 82% of cases, respectively. Hyperamylasemia is a nonspecific finding and can be seen with bowel injuries and salivary gland contusion from head injuries. The degree of serum hyperamylasemia does not correlate with the severity of pancreatic injury and may actually be greater in patients with contusions than in those with frank transections. The retroperitoneal location of the pancreas often masks symptoms of significant injury. In some cases, the patient may be asymptomatic initially, with pain, tenderness, and abdominal distention developing gradually in a 12- to 24-hour period. Peritoneal lavage results are usually negative if the peritoneum overlying the pancreas remains intact. Another clinical sign recently shown to correlate with the presence of pancreatic injury in children is the “seat belt sign.” Pancreatic injury was 22 times more commonly present in children with this sign (erythema, ecchymoses, and abrasions across the patient’s abdominal wall resulting from the vehicle’s seat belt restraint).

Surgical Classification

Box 99-1 details the classification system proposed by the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma that describes pancreatic injuries. This remains the most recent classification system and is still in use. It addresses key issues that are of importance to both the surgeon and the radiologist: the depth and location of the pancreatic injury, the degree of parenchymal disruption, and the integrity of the ampulla and main pancreatic duct. It acknowledges the significance of more complex injuries to the pancreas, particularly injuries that affect the pancreatic duct and the head of the gland; it also allows correlation with other organ injury scales.

| Grade | Injury Description |

|---|---|

| Minor contusion without ductal injury |

| Superficial laceration without ductal injury |

| Major contusion without ductal injury or tissue loss |

| Major laceration without ductal injury or tissue loss |

| Distal transection or pancreatic parenchymal injury with ductal injury |

| Proximal transection or pancreatic parenchymal injury involving the ampulla |

| Massive disruption of the pancreatic head |

Radiologic Findings

Computed Tomography

CT is the preferred means of evaluating patients with blunt abdominal trauma. Pancreatic lacerations are often subtle relative to injuries involving the liver, spleen, or kidneys and difficult to visualize on imaging studies immediately after trauma. With continued improvements in MDCT technology, near-isotropic CT data sets with three-dimensional postprocessing techniques may improve detection and characterization of pancreatic lacerations. Focal pancreatic enlargement and peripancreatic fluid are suggestive of pancreatic injury, and faint lacerations or fracture lines may be seen on closer inspection ( Figs. 99-1 and 99-2 ). The radiologist must rely on secondary findings because many injuries are manifested as pancreatitis with diffuse or focal swelling of the pancreas. Minor thickening of the anterior limb of Gerota’s fascia and fluid or increased attenuation in the anterior pararenal space, small bowel mesentery, or transverse mesocolon may be the only CT abnormalities. Fluid between the pancreas and the splenic vein was initially thought to be a useful sign of pancreatic injury. This sign was subsequently found to be neither sensitive nor specific in a later study. Fluid in this location, however, should direct the radiologist to a closer examination of the pancreas. A list of CT findings suggestive of pancreatic injury is shown in Box 99-2 .

Pancreatic laceration or fracture

Focal (or diffuse) pancreatic enlargement

Pancreatic contusion or hematoma

Areas of diminished or heterogeneous enhancement

Fluid between the splenic vein and pancreas

Fluid in the peripancreatic fat, mesocolon, and mesentery

Peripancreatic or mesenteric fat stranding

Fluid in the anterior and posterior pararenal spaces or lesser sac

Thickening of the left anterior pararenal fascia

Dilation or discontinuity of the pancreatic duct

Peripancreatic fluid collections, including pseudocyst formation

Abscess or fistula formation

Injuries to adjacent structures, including the duodenum, liver, and spleen

A major limitation of CT in pancreatic injury is that it often cannot reliably assess the integrity of the pancreatic duct. Several postprocessing techniques, including curved planar reformats and minimum intensity projection images, that are now feasible with isotropic or near-isotropic data sets have resulted in improvements in the visualization of the pancreatic duct by MDCT, but they still require validation in the trauma setting. As CT still may not directly show the pancreatic duct injury, such injury may be suspected on the basis of the degree of parenchymal injury. In addition, the pancreas may appear relatively normal on initial examinations. It has been reported that in 20% to 40% of patients with acute blunt pancreatic trauma, the pancreas can appear normal, especially within 12 hours after the injury.

Later examinations may demonstrate injuries not seen on the initial examination; however, this may relate to the characteristic evolution of pancreatic injury rather than an inaccurate initial examination. The tear progressively increases in size and becomes more well defined, often associated with extrapancreatic fluid collections. Repeated scanning in 12 to 24 hours can be helpful if there is a strong suspicion for fracture in the face of a negative CT result. Some of the prior reports of poor results with CT examination may in part relate to the studies being performed without helical or MDCT scanners, thin slices, and optimal intravenous contrast material or with lack of oral contrast material. Sensitivity and specificity of CT in pancreatic injury have improved with the use of MDCT and thinner collimation.

MDCT findings of pancreatic duct injury are either highly sensitive and nonspecific or insensitive and specific. For example, in a study aimed at evaluation of blunt pancreatic trauma with MDCT, it was determined that the finding of low-attenuation peripancreatic fluid was 100% sensitive and only 4.9% specific. Alternatively, identification of pancreatic laceration involving more than 50% of the parenchymal width had a sensitivity of 50% and a specificity of 95.1%.

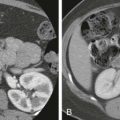

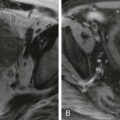

Pancreatic contusions most often are isodense but occasionally may present as hyperdense masses because of intraparenchymal hemorrhage or may be hypodense due to edema ( Fig. 99-1 ). A laceration through the pancreas is usually manifested by a thin linear lucency ( Fig. 99-2 ). Pancreatic fractures may be seen as well-demarcated lucent defects traversing the gland, generally involving the neck of the pancreas perpendicular to its long axis ( Figs. 99-3 and 99-4 ). There is often little or no separation of the pancreatic fragments, and the density change can be subtle but may be obscured by surrounding hematomas and fluid collections or streak artifacts. Dynamic scanning after bolus injection of contrast medium is important in fracture detection because it improves visualization of normal enhancing pancreatic parenchyma. Pseudocysts may form within a few days after pancreatic duct laceration and appear similar on CT to pseudocysts from pancreatitis ( Fig. 99-5 ).

Ultrasound

Although ultrasound is sensitive to demonstrate intra-abdominal fluid (hemoperitoneum), it has limited value to demonstrate pancreatic injuries. Ultrasound in pancreatic injury can miss associated hemorrhage because of the retroperitoneal location of the pancreas. The actual pancreatic parenchymal injury may be difficult to visualize sonographically. In addition, many of these patients have an associated ileus, limiting sonographic evaluation of the pancreas. The sonographic findings may be relatively subtle, usually demonstrating nonspecific gland enlargement caused by pancreatitis or contusion. The sensitivity of conventional ultrasound in the diagnosis of pancreatic trauma is reported to be low (45.7%-63%).

Even with these limitations, ultrasound is usually the first-choice screening test in the pediatric patient. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound is an imaging modality that has shown promise for the assessment of hepatic, splenic, and renal trauma. Although little research has focused on contrast-enhanced evaluation for pancreatic trauma, there are a few animal-based studies that show promise. Similar to conventional ultrasonography, the portability and cheaper cost are major benefits.

Magnetic Resonance Pancreatography

MR pancreatography (MRCP) has recently been established as a superb alternative for direct imaging of the pancreatic duct. Advantages of MRCP over ERCP include its noninvasiveness, decreased cost, and wider availability. Furthermore, MRCP allows assessment of the whole pancreatic anatomy, including not only the pancreatic duct but also the parenchyma. In addition, this imaging modality allows assessment of any peripancreatic collections and of the pancreatic duct beyond a site of disruption ( Fig. 99-5 ). MRCP may also reveal ductal abnormalities, such as pancreas divisum, important information for the endoscopist to know before ERCP. MRI has been shown to accurately detect disruption of the pancreatic duct.

Newer refinements and technical advances in MRCP, including secretin-enhanced MRCP, provide additional information. Dynamic assessment improves detection of pancreatic ductal anatomy and presence of leak after trauma.

Pancreatic injuries rarely occur in isolation, and MRI also allows assessment of additional organs in the upper abdomen, including the liver, kidneys, and spleen.

The exact role of MRCP in the setting of acute pancreatic injury has not yet been established. Controversy exists about its usefulness as a screening tool in the acute setting. As MRI becomes more widely available and technology continues to improve, more studies and clinical experience are needed to establish the exact role of MRCP in acute pancreatic injury.

Conventional Pancreatography

The main pancreatic duct is a rigid and brittle structure compared with the pancreatic parenchyma. Accordingly, the duct may be lacerated without producing cross-sectional imaging abnormalities or surgically detectable peripancreatic hemorrhage or capsular disruption. The diagnosis can be missed at the time of surgical exploration, and this has led some surgeons to advocate routine intraoperative or preoperative pancreatography to avoid the morbidity and mortality of an unsuspected or a misdiagnosed ductal disruption. ERCP is not an appropriate screening test for pancreatic trauma; furthermore, the role of MRCP in this setting has not yet been firmly established. However, in cases in which the CT scan or MRCP study is equivocal or technically inadequate, emergent ERCP is useful in identifying the presence and location of pancreatic duct disruption. Demonstration of a normal duct can obviate the need for exploratory surgery in these patients. The technique is not universally available, especially on an emergent basis. In addition, patients must be clinically stable for the examination. The ductal transection appears as either duct obstruction or extravasation of contrast material from the pancreatic duct. ERCP is also useful in detecting post-traumatic pancreatic ductal strictures and pseudocyst communication.

Gastrointestinal Studies

Pancreatic trauma is often associated with duodenal injury. When coexisting pancreatic and duodenal injuries are suspected, water-soluble agents can disclose duodenal perforation or mass effect involving the duodenum from acute pancreatitis or pseudocysts.

Treatment

The first priority in pancreatic trauma is to control hemorrhage and to contain bacterial contamination. The other main management priority is the identification of specific pancreatic injury with special attention to the integrity of the ductal system. Ductal injury is the single most important factor in late morbidity and mortality. Most pancreatic injuries can be managed with closed external drainage. Débridement of devitalized pancreatic tissue adjacent to the fracture site is essential in severe pancreatic injuries. It is important, however, to preserve at least 20% to 50% of functional pancreatic tissue whenever possible. Resection should be accompanied by drainage and duodenal diversion for concurrent pancreatic head and duodenal injuries. If there is only a contusion or laceration without evidence of major duct disruption, suture closure and external drainage usually suffice. Severe injuries of the pancreatic head can be managed according to their appearance on intraoperative pancreatography. If the duct is intact, wide-bore drainage should suffice. If duct injury is demonstrated, a Roux-en-Y diversion may be considered. However, increased complication rates of up to 60% have been reported in patients with high-grade injuries treated with pancreaticojejunostomy, suggesting that distal pancreatectomy, when feasible, is a superior operative treatment for these patients.

Controversy exists about the optimal management of grade III injury of the left pancreas. Drainage alone was effective in 54 of 63 patients with gunshot wounds, with low mortality, but many complications were seen, generally related to the large number of associated organ injuries. Another group performed distal pancreatectomy and splenectomy in 48 of 57 patients with gunshot wounds to the left aspect of the pancreas, also with a low mortality rate but many complications due to associated organ injury. Patients who had distal pancreatectomy with splenic preservation had a significantly lower complication rate (22% vs 73%); however, this is probably due to increased comorbidities, such as associated visceral or splenic injury and the emergent nature of the surgery. The decision about whether to salvage all or part of the spleen is based on both patient hemodynamics and age. Again, overlooked or underestimated pancreatic injury can lead to potentially disastrous complications. Pancreatic abscesses may develop owing to inadequately drained fluid collections that become infected from intestinal spillage or bacteremia.

Endoscopic pancreatic duct stent placement has been described in the literature, with good results. Case reports have described good short-term results and a potential role in the delayed management of traumatic pancreatic duct disruption with endoscopic pancreatic duct stenting. Successful outcomes with pancreatic duct stenting were described in partially disrupted ducts with placement of a bridging stent. However, whereas good short-term results have been reported with duct stenting, later complications, including stricture formation, inability to subsequently remove the stent, and stent migration, raise questions about the utility of this procedure in the acute phase. More important, pancreatic duct stenting in the acute phase may delay timely operative intervention and definitive repair of life-threatening injuries. Therefore, it has been proposed that pancreatic duct stenting be used later to treat post-traumatic pancreatic fistulas.

The optimal management of pancreatic injuries in children has remained controversial. Similar to nonoperative management of splenic and hepatic injuries, there has been a trend toward nonoperative management of pancreatic injuries in children without major ductal injuries or clinical deterioration. ERCP has been advocated for management of these children; demonstration of a transected pancreatic duct typically requires exploratory laparotomy with a spleen-preserving distal pancreatectomy. There is limited experience of endoscopic treatment with stent placement in the pediatric population. In a small series of nine children with main duct injury treated by an endoscopically placed stent, all children managed with therapeutic ERCP avoided pancreatic resection, although most (66%) developed pancreatic fluid collections requiring drainage.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree