Paranasal Sinuses, Nasal Cavity, and Face

The roof of the nasal cavity is formed by the cribriform plate and the floor by the hard palate. The olfactory mucosa is found in the upper portion of the nasal cavity, above the superior turbinates. The nasal septum is formed by the ethmoid bone posteriorly, cartilage anteriorly, and the vomer posteroinferiorly. The turbinates (nasal concha), of which there are three (inferior, middle, and superior), lie along the lateral walls of the nasal cavity, with a space (meatus) beneath each turbinate, named according to the turbinate immediately above. The nasolacrimal duct opens into the inferior meatus. The semilunar hiatus is a crescent-shaped groove in the middle meatus, with the ostium for the maxillary sinus located posteriorly therein. The ostium lies high on the medial sinus wall. Therefore, gravity cannot drain the maxillary sinus. There is a normal nasal cycle, with alternating partial congestion and decongestion of the nasal turbinates with time, from the left side to the right side, which can be commonly observed on imaging, either with the appearance of unilateral congestion or with alternation between different exams of the side of congestion.

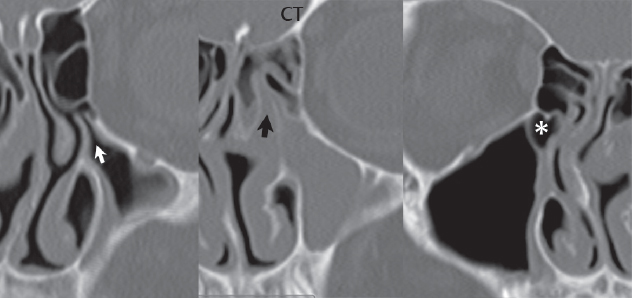

The frontal sinus is typically divided by a septum along the midline, with the two resulting sinuses usually asymmetric in size, but each a single cavity. The ethmoid sinuses, which are composed of multiple individual small air cells, are today typically divided into anterior and posterior groups. In regard to the sphenoid sinus, pneumatization varies widely. There is typically a septum which is midline anteriorly, but can deviate to one side posteriorly. Two major air cells are common for the sphenoid sinus, with one often substantially larger than the other. Extension of the sphenoid sinus, specifically the lateral recesses, into the greater wing of the sphenoid, is common. The maxillary sinuses are usually symmetric. Asymmetry in size should immediately raise the question of chronic sinus disease (with chronic sinusitis leading to a small sinus with thickened walls.). Plain film exam grossly underestimates the extent of soft tissue disease and bone erosion/destruction versus cross-sectional imaging. CT of the paranasal sinuses is often reformatted in a tilted coronal plane, which well displays the ostiomeatal unit ( Fig. 2.51 ). This term refers to the collecting channel that drains the anterior ethmoid air cells and frontal and maxillary sinuses into the middle meatus. The posterior ethmoid air cells and the sphenoid sinus drain via the sphenoethmoidal recess into the superior meatus. Viewing of images reconstructed with both soft tissue and bone algorithms on CT is recommended. MR, as always, offers superior soft tissue visualization/differentiation, but inferior depiction of fine bony change.

Inflammation/Infection

Acute bacterial sinusitis can occur following viral infection (the “common cold”), with mucosal inflammation and swelling of the turbinates causing obstruction of the sinus ostia, which then leads to bacterial infection. Dental infection or tooth extraction can also lead to acute bacterial sinusitis. The clinical presentation is one of pain over the affected sinus, with mucopurulent discharge. Disease is often limited to a single sinus. With repeated or persistent infection (chronic sinusitis), the bony walls of the sinus become thickened and sclerotic. With persistent maxillary obstruction, hypoventilation and negative pressure occur leading to retraction of the sinus walls and craniocaudad orbital enlargement and enophthalmos (silent sinus syndrome). Allergic sinusitis is characterized by symmetrical involvement and nasal polyposis (a differentiating point from bacterial sinusitis). However, profuse secretions in this disease process, with resultant obstruction, can lead to bacterial sinusitis.

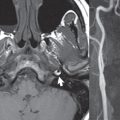

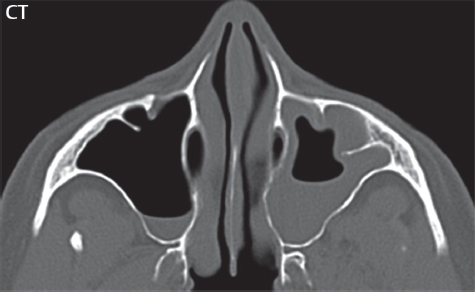

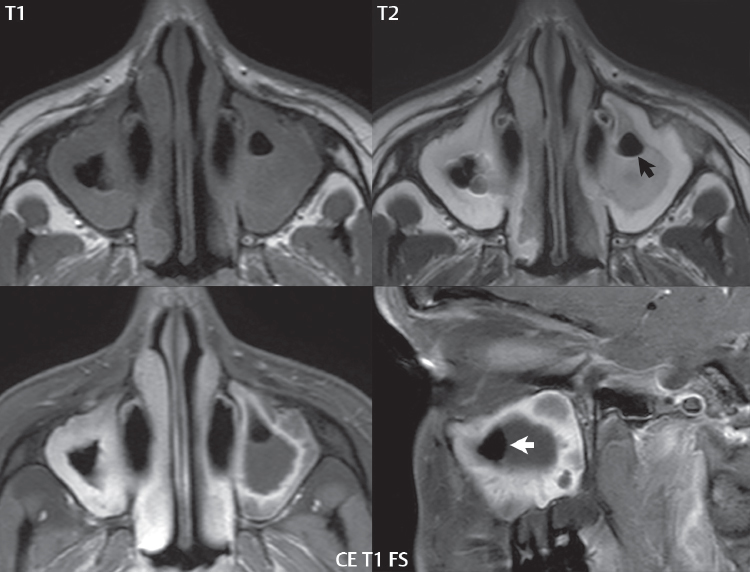

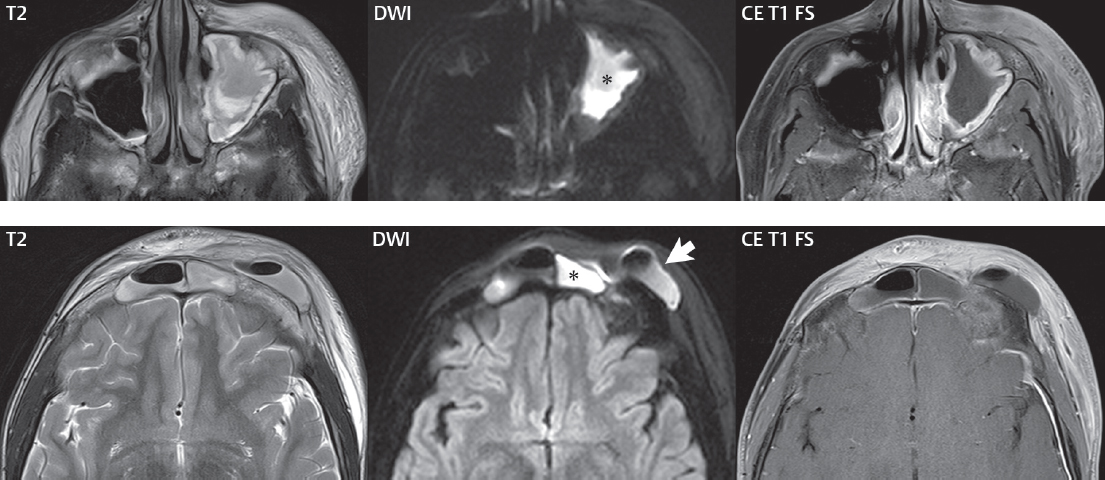

The most reliable sign of acute bacterial sinusitis on imaging is the combination of mucosal thickening with an air–fluid level (Figs. 2.52 and 2.53). Another presentation is that of complete sinus opacification by fluid (typically easily identified, and differentiated from soft tissue, on T2-weighted images), with DWI an important additional MR sequence (for identification of infection). Of all the paranasal sinuses, the maxillary sinus is the most commonly involved ( Fig. 2.54 ). Other causes of an air–fluid level include trauma (with hemorrhage), placement of a nasal tube, and sinus lavage. Complications from paranasal sinusitis include orbital involvement (most often due to ethmoid sinus infection), meningitis, intracranial abscess formation, subgaleal abscess (Pott puffy tumor, most often from frontal sinus involvement), and osteomyelitis (in patients with chronic disease) ( Fig. 2.55 ). Intracranial spread of infection (cerebritis, epidural abscess, etc.), involving the anterior cranial fossa, can occur within 48 hours following development of frontal sinusitis (due to the rich venous network).

Cysts and polyps are a common local complication of inflammation. A very large cyst can resemble an air–fluid level on imaging, with close inspection of images mandated, in particular considering the direction of gravity and inspection of the cyst/fluid border, which should be slightly convex with a cyst. A mucous retention cyst is the most common of the different cysts and polyps, with the floor of the maxillary sinus the most frequent location ( Fig. 2.56 ). A mucous retention cyst is generally considered an incidental finding. A polyp is due to a local upheaval of mucosa, with the two common etiologies being inflammation and allergy (with allergic polyps being multiple). Polyps can be expansile in nature, cause bony destruction, and most often involve the maxillary sinus. As the polyp expands in size, it may prolapse through the sinus ostium, forming an antrochoanal polyp (in the literature 5% of all polyps, thus not uncommon) ( Fig. 2.57 ).

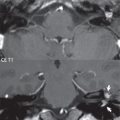

The most common causes of invasive fungal sinusitis include aspergillosis, mucormycosis, and candidiasis. Mucormycosis especially occurs in poorly controlled diabetes and other chronic disease states. Candidiasis occurs in immunocompromised patients. Fungal sinusitis often involves multiple sinuses, with additional clues being increased attenuation (calcification) within the opacified sinus on CT and hypointense signal intensity on T2-weighted scan centrally ( Fig. 2.58 ). Orbital and intracranial complications are not uncommon, including cavernous sinus thrombosis.

Two additional entities that involve the paranasal sinuses are of note. Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (previously termed Wegener granulomatosis) is a necrotizing vasculitis, which can affect the nose and paranasal sinuses. The common presentation, when there is nasal involvement, is that of a soft tissue mass involving the nasal cavity with bone destruction (septal perforation). On MR, the mass will be low signal intensity on T2-weighted images, with homogeneous enhancement postcontrast. Cocaine abuse also causes a necrotizing vasculitis, with inflammatory changes and septal erosion/perforation ( Fig. 2.59 ).

Mucoceles are the most common expansile lesion involving a paranasal sinus ( Fig. 2.60 ). A mucocele is caused by obstruction of a sinus ostium (or of a compartment in a septated sinus). The incidence, by sinus, is frontal > ethmoid > maxillary > sphenoid. The sinus will be devoid of air and expanded, with remodeling of the walls. The most common appearance on MR is low on T1 and high on T2. If present for a long time the signal intensity on T1 may be high, due to protein content and resorption of water.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree