Parasites are defined as organisms that live in or on another living organism, obtain part or all of their organic nutriment from that organism, and cause some degree of damage to their host. Parasitic infestations occur mainly in tropical and subtropical regions. Pulmonary disease secondary to parasites in North America and Europe is seen in individuals who traveled to endemic areas and in recent immigrants. Parasites that most commonly result in pulmonary disease include protozoa (amebiasis), nematodes (ascariasis and strongyloides), cestodes (echinococcosis), and trematodes (schistosomiasis and paragonimiasis). Although rare in the United States and in other developed countries, parasitic diseases should at least be considered in the following situations:

- 1.

Peripheral blood eosinophilia

- 2.

Recent travel to or emigration from endemic areas

- 3.

Migratory pulmonary opacities or nodules without obvious cause

- 4.

Exacerbation of pulmonary disease after administration of corticosteroids

- 5.

Development of peripheral blood eosinophilia after administration of corticosteroids

Amebiasis

Etiology, Prevalence, and Epidemiology

Amebiasis is a protozoan infection caused by Entamoeba histolytica, a species usually associated with colonic disease (amebic dysentery). It is estimated to affect about 1% of the world population and to result in 40,000 to 110,000 deaths annually. The infestation is acquired by ingestion of cysts that become trophozoites in the colon. The prevalence of infection is highest in areas of crowding, areas of poor sanitation, and the tropics. Most cases in the United States develop in immigrants from endemic regions who have been in the country for less than 2 years.

The most common extraintestinal manifestations of amebiasis are liver abscess and pleuropulmonary involvement. Pleuropulmonary extension occurs in 6% to 40% of patients with amebic liver abscess. Less commonly, it may result from aspiration or hematogenous dissemination.

Clinical Presentation

Patients with amebic liver abscesses are usually febrile and typically present with right upper quadrant pain. Gastrointestinal symptoms, mainly diarrhea, may or may not be present. Extension into the pleural space usually is associated with acute onset of sharp lower thoracic pain that frequently radiates to the ipsilateral shoulder, cough, progressive dyspnea, and evidence of sepsis.

Pathophysiology

The cysts are passed in the feces of affected individuals (who are frequently asymptomatic) and are ingested by the new host in contaminated water or food. The ingested cysts of E. histolytica travel to the small intestine, where the trophozoites excyst. They later migrate to the colon, where they multiply and, in some cases, pass through the epithelium into the submucosa. Penetration of the mucosa is associated with necrosis, ulceration, and characteristic symptoms of amebic dysentery. The organism subsequently may enter the colonic venous circulation and pass via the portal veins to the liver, where abscesses may develop. Amebic liver abscesses are usually solitary and affect the right lobe in 80% of cases. The abscesses contain sterile pus and reddish brown (“anchovy-paste”) liquefied necrotic liver tissue.

Pleuropulmonary manifestations of amebiasis usually occur by direct extension of disease from a hepatic abscess. Such abscesses may extend into the subphrenic space and form a separate subdiaphragmatic abscess, resulting in elevation of the diaphragm and pleural effusion. The abscesses may also extend through the diaphragm and involve the pleura and lung. Greater than 95% of amebic lung abscesses develop in parenchyma contiguous to the diaphragm.

Manifestations of the Disease

Radiography

The most common radiographic manifestations in the chest consist of elevation of the right hemidiaphragm ( Fig. 14.1 ), pleural effusion, and atelectasis or consolidation in the right lower lobe. The effusion can be sterile, reflecting the presence of inflammatory pleural reaction, or represent an empyema if the hepatic abscess ruptures and traverses the diaphragm. Pulmonary involvement results in airspace consolidation and cavitation. The pulmonary abnormalities are typically adjacent to the diaphragm.

Drainage of the liver abscess into a bronchus may result in hepatobronchial or bronchobiliary fistula. Invasion of the inferior vena cava occurs occasionally and may result in pulmonary thromboembolism.

Computed Tomography

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) allows assessment of the liver abscess (see Fig. 14.1 ) and its extension into the subphrenic space or across the diaphragm into the pleura or lung. It also is superior to the radiograph in showing the presence of amebic lung abscess. Liver abscesses typically are round and have smooth margins and a low-attenuation center surrounded by a contrast-enhancing rim. Uncommonly, the hepatic abscess may communicate with the pericardial space, leading to pericardial effusion, tamponade, or pericarditis.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Amebic liver abscesses, similar to abscesses of other etiology, usually appear as sharply circumscribed, heterogeneous, low–signal intensity masses on T1-weighted images. T2-weighted images typically show the abscess cavity as a hyperintense region, often surrounded by a rim of increased signal intensity extending from the cavity margins to the liver surface, corresponding to edematous but morphologically normal liver tissue.

Ultrasonography

Ultrasonography shows the size and position of the liver abscess. Aspiration of the abscess contents may be performed under ultrasound guidance but is indicated only if rupture of the abscess is considered to be imminent. Amebae are seldom recovered from the aspirate.

Imaging Algorithm

The clinical manifestations are mainly related to the amebic liver abscess. The initial diagnostic modality is usually ultrasound or CT of the liver. Ultrasonography is the recommended examination because of its low cost and lack of radiation. The thoracic manifestations are typically assessed on the chest radiograph. Contrast-enhanced CT scans of the chest and abdomen are recommended in patients with suspected intrathoracic extension of liver abscess.

Differential Diagnosis

Amebic liver abscesses resemble pyogenic abscesses on ultrasound and CT. Suspicion of amebic abscess is based on clinical history. A positive diagnosis can be made by showing organisms in sputum, pleural fluid, or material obtained by needle aspiration. A presumptive diagnosis can be made if trophozoites or cysts are identified in stool.

Synopsis of Treatment Options

Most uncomplicated amebic abscesses resolve after treatment with metronidazole. Patients who do not respond to medical therapy may require percutaneous catheter drainage of the liver abscesses. Drainage can be performed under ultrasound or CT guidance.

- •

Amebiasis is caused by E. histolytica.

- •

Endemic areas include tropical regions and areas of poor sanitation.

- •

The most common extraintestinal manifestation of amebiasis is liver abscess.

- •

The most common radiologic manifestations of amebiasis include:

- •

Elevation of right hemidiaphragm

- •

Pleural effusion

- •

Consolidation and atelectasis of right lower lobe

- •

- •

CT and ultrasonography are helpful to diagnose liver abscess

Ascariasis

Etiology, Prevalence, and Epidemiology

The nematodes Ascaris lumbricoides and, less commonly, Ascaris suum are acquired by ingesting food or fluids contaminated with feces. The infection is distributed worldwide and is one of the most common parasitic infections, affecting 1.3 billion people and causing about 1550 deaths per year. Parasites migrate from the small intestine to the pulmonary circulation, where they mature and destroy capillaries and alveolar walls with subsequent edema, hemorrhage, and epithelial cell desquamation, causing chemotaxis of neutrophils and eosinophils.

Clinical Presentation

Clinical manifestations of pulmonary involvement include low-grade fever, cough, and expectoration. Leukocytosis of 20,000 to 25,000 cells/mm 3 is common, with an eosinophilia of 30% to 70%. Pulmonary disease is usually self-limited.

Pathophysiology

The adult worm lives in the small intestine. The eggs are passed in the feces. When ingested the ovum hatches in the small intestine, and the larvae enter the portal veins or intestinal lymphatics. From there they pass to the lungs, where they are trapped by the alveolar capillaries, and exit into the airspaces. At this point they develop into third-stage larvae that migrate up the airways to the larynx, where they are swallowed to complete their cycle by developing into mature worms in the small intestine.

Pulmonary disease usually results from passage of the larvae through the lungs. The histologic findings include patchy interstitial thickening, an inflammatory exudate composed largely of eosinophils, and alveolar hemorrhage and edema.

Manifestations of the Disease

Radiography

The chest radiograph shows migratory, patchy airspace opacities that characteristically clear within 10 days. Lobar consolidation and alveolar hemorrhage have also been described. The Ascaris worms sometimes may be seen on radiographs of the abdomen outlined against intestinal gas.

Computed Tomography

The chest CT findings consist of patchy bilateral ground-glass opacities, subpleural nodules with or without a halo of ground-glass opacity (CT halo sign), and focal areas of consolidation without any zonal predominance, typical of eosinophilic pneumonia. CT of the abdomen shows the Ascaris as cylindrical filling defects within contrast-filled bowel loops. The intestinal tract of the roundworm itself is often seen as a thin thread of oral contrast material within the tubular filling defect.

Imaging Algorithm

In most cases chest radiography is the only imaging modality performed in patients with suspected eosinophilic lung disease secondary to Ascaris infestation.

Differential Diagnosis

The radiologic manifestations in the lungs are similar to the manifestations seen in strongyloidiasis: simple pulmonary eosinophilia and eosinophilic reaction to drugs. The diagnosis is confirmed by identifying larvae in the sputum or eggs in the stool.

Synopsis of Treatment Options

Acceptable treatments include albendazole or mebendazole.

- •

Ascariasis is caused by A. lumbricoides.

- •

Infestation is common in Southeast Asia, South America, Africa, and the United States.

- •

The most common pulmonary manifestation is eosinophilic lung disease.

- •

The most common radiologic manifestations include:

- •

Patchy bilateral areas of consolidation or ground-glass opacities

- •

Typically migratory and transient opacities

- •

Strongyloidiasis

Etiology, Prevalence, and Epidemiology

Humans are the primary host of Strongyloides stercoralis, a microscopic nematode with infective larvae that invade the lungs and small intestine by migrating from the soil through the skin. The parasite is found in all tropical and subtropical regions. About 35 million people are infected worldwide. The highest infection rates in the United States are in the Southeast and Puerto Rico.

Clinical Presentation

Clinical manifestations include cough, shortness of breath, and bronchospasm. Abdominal symptoms, including diarrhea, weight loss, and midepigastric pain, are commonly present. The patients usually have peripheral eosinophilia. Severely immunocompromised patients may develop disseminated Strongyloides infection that manifests as fever, cough, and rapidly progressive and severe shortness of breath. Abdominal pain and diarrhea are present in most patients.

Pathophysiology

The infective larvae migrate from the soil through the skin, eventually reaching the small intestine, where the adult worm resides. Pulmonary disease is caused mainly by the migration of larvae through alveolar capillaries into airspaces. Normal migration results in eosinophilic lung disease or mild intraalveolar hemorrhage.

Disseminated Strongyloides infection (hyperinfection syndrome) is an uncommon complication that may occur in immunocompromised patients. In these patients larvae may disseminate and involve multiple organs, including the brain. The most common manifestation of Strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome is extensive alveolar injury and pulmonary hemorrhage. The mortality in these patients can exceed 70%.

Manifestations of the Disease

Radiography

Radiographic manifestations consist of ill-defined, patchy areas of consolidation, presumably caused by an allergic reaction to migration of the filariform larvae through the lungs. The areas of consolidation may be migratory and typically resolve within 1 to 2 weeks.

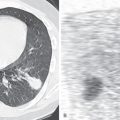

Hyperinfection may result in extensive bilateral consolidation or diffuse reticulonodular or nodular pattern ( Fig. 14.2 ). The nodules may have poorly defined or well-defined margins. Occasionally, the findings may resemble miliary tuberculosis. Pleural effusion and secondary superimposed bacterial infection with cavitation and abscess formation may also be seen.

Computed Tomography

The chest CT findings in eosinophilic reaction to the passage of larvae through the lungs consist of migratory patchy bilateral ground-glass opacities and focal areas of consolidation without any zonal predominance.

Imaging Algorithm

In most cases chest radiography is the only imaging modality performed in patients with suspected eosinophilic lung disease secondary to Strongyloides.

Differential Diagnosis

The radiologic manifestations of strongyloidiasis, similar to those of ascariasis, usually result from eosinophilic lung disease secondary to normal passage of larvae through the lungs and are similar to the radiologic manifestations of simple pulmonary eosinophilia and eosinophilic reaction to drugs. The diagnosis is usually confirmed by detection of larvae in the stool.

The differential diagnosis of hyperinfection includes opportunistic infection, diffuse pulmonary hemorrhage, and acute respiratory distress syndrome from any cause. Definitive diagnosis is made by identifying the larvae in the sputum.

Synopsis of Treatment Options

Treatment is with antiparasitic drugs such as ivermectin.

- •

Strongyloidiasis is caused by S . stercoralis.

- •

Infestation occurs in tropical and subtropical countries and the southeastern United States.

- •

The most common pulmonary manifestation is eosinophilic lung disease.

- •

The most common radiologic manifestations include:

- •

Patchy bilateral areas of consolidation or ground-glass opacities

- •

Typically migratory and transient opacities

- •

Occasionally, hyperinfection in immunocompromised patient may result in extensive consolidation and a diffuse reticulonodular or nodular pattern

- •

Echinococcosis (Hydatid Disease)

Etiology, Prevalence, and Epidemiology

Hydatid disease is caused by small larvae of Echinococcus, usually Echinococcus granulosus. It occurs in two forms: pastoral and sylvatic. The pastoral form is more common and is seen mainly in the Mediterranean region, eastern Europe, South America, the Middle East, Australia, and New Zealand. The intermediate hosts are usually sheep, cows, or pigs, and the definite hosts are dogs. The sylvatic form is more common in Alaska and northern Canada. The intermediate hosts of the sylvatic variety are usually moose, deer, or caribou, and the definite hosts are dogs, wolves, and coyotes.

Clinical Presentation

Most patients are asymptomatic. Cyst rupture, either spontaneous or as a result of secondary infection, may result in abrupt onset of cough, expectoration, and fever. Occasionally, cyst rupture results in acute hypersensitivity reaction, with urticaria, pruritus, and in some cases hypotension.

Pathophysiology

Humans acquire the disease by direct contact with definite hosts or by ingestion of eggs present in water, food, or soil. The eggs hatch in the duodenum into larvae that pass via the portal system to the liver, where most are trapped. Most larvae that escape are trapped in pulmonary alveolar capillaries. In the pastoral variety, approximately 65% to 70% of cysts occur in the liver and 15% to 30% in the lungs. For reasons that are unclear, lung cysts seem to be more common than liver cysts in the sylvatic variety of hydatid disease.

In liver and lung the larvae develop into cysts that are typically spherical or oval in shape. The cysts are surrounded by an outer protective layer termed the pericyst , which consists of fibrous tissue containing a nonspecific chronic inflammatory infiltrate. The surrounding lung usually shows compressive atelectasis. The cyst itself consists of a laminated, acellular layer (the ectocyst) and a thin inner germinal layer (the endocyst) that contains intracystic fluid, daughter vesicles, daughter cysts, and larval protoscoleces. A multicystic structure may result from serial cyst formation over several generations.

Manifestations of the Disease

Radiography

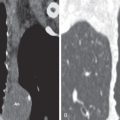

Hydatid cysts manifest as sharply circumscribed spherical or oval masses surrounded by normal lung ( Fig. 14.3 ). They are most commonly single but may be multiple in 30% of patients. Their size ranges from 1 cm to greater than 20 cm in diameter. Most are located in the lower lobes. Although usually spherical or oval, hydatid cysts may have an irregular shape, attributed by some to the fact that they impinge on relatively rigid structures, such as bronchovascular bundles, as they grow and become indented and lobulated. When communication develops between the cyst and the bronchial tree, air may enter the space between the pericyst and exocyst and produce a thin crescent around the periphery of the cyst—the meniscus or crescent sign. After the cyst has ruptured into an airway, its membrane may float on residual fluid within the cyst and give rise to the classic water lily sign ( Figs. 14.4 and 14.5 ).