Part 10: Pediatric or Developmental Musculoskeletal Conditions

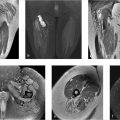

Case 126

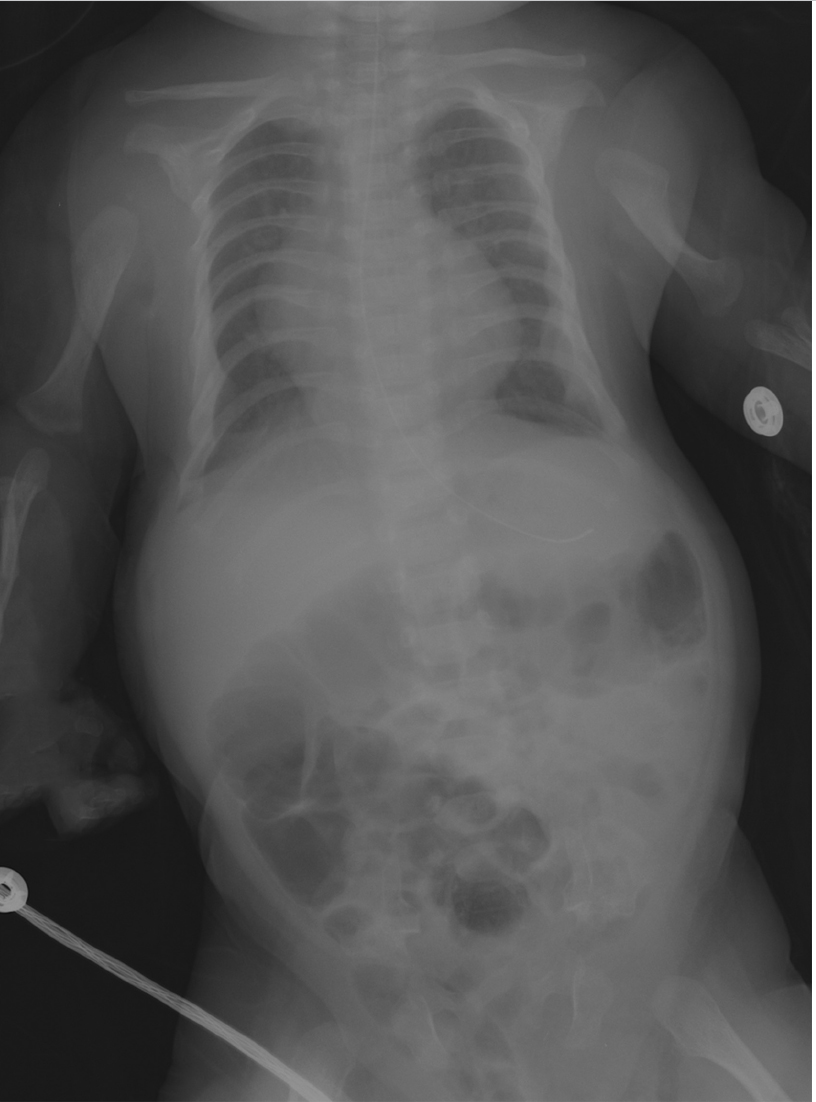

Key Finding

Short rib skeletal dysplasia.

Top 3 Differential Diagnoses

Asphyxiating thoracic dystrophy (Jeune syndrome): In this syndrome, the thorax is long and bell-shaped, with short, horizontal ribs that flare anteriorly. This configuration results in early respiratory compromise. Dysplastic acetabula resembling an upside-down trident is often seen. There is associated mild acromelic (distal) limb shortening, but long bones are not bowed. A normal spine and trident acetabula help differentiate this condition from thanatophoric dysplasia.

Ellis-van Creveld syndrome (chondroectodermal dysplasia): Hair, nail, and teeth abnormalities are clinical hallmarks of this syndrome. There is progressive mesomelic (middle–tibial and radial) and acromelic (distal) limb shortening. The fibulae are markedly shortened. Radiographic features also include short ribs, fused capitate and hamate, cone-shaped epiphyses, and postaxial polydactyly. The femoral heads ossify prematurely, and the pelvis is abnormal, with flared iliac wings and a trident acetabulum. Congenital heart disease, typically atrial septal defect or atrioventricular cushion defect, is the major cause of morbidity.

Short rib polydactyly: In this condition, the ribs are extremely short. Polydactyly may be either preaxial or postaxial. The pelvis and spine appear fairly normal, and long bones are normal. However, there may be cleft palate, hypoplastic epiglottis, cystic kidneys, and fetal hydrops.

Additional Diagnostic Considerations

Thanatophoric dysplasia: Thanatophoric dysplasia is the most common lethal skeletal dysplasia which is uniformly fatal in the neonatal period. The ribs are very short, and as a result, the thorax is narrow. Lung hypoplasia causes respiratory failure. Patients with this disproportionate dwarfism have severe platyspondyly but wide intervertebral disks, leading to normal trunk length. The head is disproportionately large, and some patients have cloverleaf skull. Iliac bones are small. There is rhizomelic (proximal) limb shortening. Long bones are bowed and short. The femurs have a characteristic “telephone receiver” appearance.

Holt–Oram syndrome: Like Ellis-van Creveld, this condition is characterized by cardiac disease (usually an atrial or ventricular septal defect) and limb abnormalities. However, the ribs are normal. The thumb is usually duplicated, hypoplastic, or triphalangeal. The radius is often hypoplastic, and there may be other anomalies of the shoulder and upper extremity.

Diagnosis

Ellis-van Creveld syndrome.

Pearls

Jeune syndrome (asphyxiating thoracic dysplasia) demonstrates a bell-shaped thorax, trident acetabula, and normal spine.

Patients with Ellis-van Creveld have cardiac disease as well as progressive limb shortening, short ribs, and postaxial polydactyly.

Bones in patients with short rib polydactyly are otherwise normal.

Suggested Readings

- 433 Glass RB, Norton KI, Mitre SA, Kang E. Pediatric ribs: a spectrum of abnormalities.. Radiographics 2002; 22 (1) 87-104 PubMed 11796901

- 434 Miller E, Blaser S, Shannon P, Widjaja E. Brain and bone abnormalities of thanatophoric dwarfism.. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2009; 192 (1) 48-51 PubMed 19098178

- 435 Panda A, Gamanagatti S, Jana M, Gupta AK. Skeletal dysplasias: a radiographic approach and review of common non-lethal skeletal dysplasias.. World J Radiol 2014; 6 (10) 808-825 PubMed 25349664

- 436 Parnell SE, Phillips GS. Neonatal skeletal dysplasias.. Pediatr Radiol 2012; 42 (Suppl. Suppl 1) S150-S157 PubMed 22395727

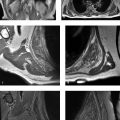

Case 127

Key Finding

Abnormal epiphyses.

Top 3 Differential Diagnoses

Spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia (SED):SED “congenita” manifests at birth with absent calcaneal, knee, and pubic bone ossification, pear-shaped vertebrae, and short, broad iliac wings. Severe platyspondyly develops, with thin intervertebral disks. SED “tarda” usually manifests at age 5 to 10 years with platyspondyly (including hump-shaped posterior vertebral bodies), small pelvis, and mild-to-moderately small, irregular epiphyses.

Chondrodysplasia punctate:There are two common subtypes, both characterized by stippled epiphyses at birth. The autosomal recessive form shows symmetrical rhizomelic shortening, stippling in the large joints, and sometimes stippling of laryngeal and tracheal cartilage. Coronal clefts are seen in vertebrae. The hands and feet are normal. The X-linked dominant type, “Conradi–Hunermann,” shows occasional and asymmetrical limb shortening and involvement of the hands and feet as well as large joints. The larynx and trachea are normal, but vertebral bodies and endplates are stippled, leading to eventual kyphoscoliosis. Stippling resolves over time, and the patients have a normal lifespan. Mental retardation is a feature of the lethal form but not Conradi–Hunermann.

Spondyloepimetaphyseal dysplasia:This dysplasia resembles multiple epiphyseal dysplasia, but there is concomitant metaphyseal involvement.

Additional Diagnostic Considerations

Multiple epiphyseal dysplasia:This genetically heterogeneous disorder presents after age 2 to 4 years. Bilateral and symmetrical, delayed and fragmented epiphyses of long bones and distal extremities are characteristic. Pronounced wedging of distal tibial epiphysis may trigger the diagnosis. The spine resembles Scheuermann disease, with endplate irregularities, slight anterior wedging, and numerous Schmorl nodes.

Morquio syndrome:A mucopolysaccharidosis, Morquio syndrome is characterized by delayed ossification of femoral heads, irregular epiphyses, and secondary metaphyseal widening. Other bones are involved as well, notably the spine, where there is platyspondyly with anterior beaking of the midportion of vertebral bodies. The bases of the 2nd through 5th metacarpals are pointed and clustered together. Ribs have a paddle appearance.

Diagnosis

Spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia.

Pearls

SED tarda manifests during childhood with mild-to-moderately small, irregular epiphyses and platyspondyly with hump-shaped posterior vertebral bodies.

A wedged, slightly small distal tibial epiphysis is a clue to the diagnosis of multiple epiphyseal dysplasia.

With Morquio syndrome, ossification of the femoral heads is delayed, and there are multiple irregular epiphyses; as far asHurler syndrome is concerned, there is anterior vertebral body beaking.

The autosomal recessive type of chondrodysplasia punctata has stippled epiphyses of large joints and less involvement of the axial skeleton, whereas with Conradi-Hunermann, the spine, hands, and feet may be affected as well.

Suggested Readings

- 437 Panda A, Gamanagatti S, Jana M, Gupta AK. Skeletal dysplasias: A radiographic approach and review of common non-lethal skeletal dysplasias.. World J Radiol 2014; 6 (10) 808-825 PubMed 25349664

- 438 Parnell SE, Phillips GS. Neonatal skeletal dysplasias.. Pediatr Radiol 2012; 42 (Suppl. Suppl 1) S150-S157 PubMed 22395727

Case 128

Key Finding

Limb deficiency.

Top 3 Differential Diagnoses

Longitudinal deficiency of the fibula: In this condition, the fibula may be partly or completely absent, or it may simply be mildly hypoplastic. The anomaly is often accompanied by proximal focal femoral deficiency, coxa vara, clubfoot, and absent lateral rays. The remainder of the skeleton is usually normal. Perhaps counter-intuitively, femoral abnormalities are more common with a hypoplastic fibula than with one that is completely absent. A cartilaginous fibular anlage is often present, which tethers growth of the tibia. If the hip and/or femur are clearly abnormal as well, the diagnosis may be made in utero. If the fibula is absent or markedly hypoplastic, X-ray diagnosis is straightforward. The tibia is often bowed, short, and thick. However, subtle cases are diagnosed by an abnormally high-distal fibular physis (above the proximal tibialphysis). Treatment is directed at establishing a usable weight-bearing lower extremity which often involves amputation. Longitudinal deficiency of the tibia is much less common than that of the fibula.

Longitudinal deficiency of the radius: This sporadic condition usually consists of complete absence of the radius. However, the deficiency may be more limited and is occasionally manifested only by absence or hypoplasia of the thumb. As many as 1/3rd of patients are otherwise normal, but 1/3rd also have a syndrome such as thrombocytopenia-absent radius (TAR), VACTERL, or Holt–Oram. As many as 1/3rd have nonsyndromic-associated bone anomalies, with the likelihood of this increasing with the severity of deficiency. The radius is partly or (more often) completely absent, and the thumb is hypoplastic or absent. The ulna is short and bowed. If the radius is partially present, it may be fused with the ulna, and the radial head is often congenitally dislocated. The hand may be at a right angle to the forearm (radial clubhand).

Proximal focal femoral deficiency (PFFD): This nonhereditary malformation ranges from mild dysgenesis of the proximal femur to near complete absence of the bone. Usually isolated and unilateral, it may be part of caudal regression syndrome. The tibia and fibula may be hypoplastic as well. The condition is classified according to the presence of the femoral head, connection between the femoral head and the shaft (bony, cartilaginous, or absent), and extent of acetabular dysplasia. US and MRI assess nonossified structures.

Additional Diagnostic Consideration

Longitudinal deficiency of the ulna: At least part of the ulna is usually present in this disorder, which is more common in boys, usually on the right, and infrequently bilateral. Anomalies of the hand, wrist, and elbow bones are more severe than with radial deficiency. Carpal bones and digits are often missing or fused. Clubhand alignment is uncommon. Remote bony anomalies are common, including scoliosis, phocomelia, and PFFD. Other organ systems are usually normal. X-rays usually show a hypoplastic ulna, with ossification sometimes delayed until age of 2 years. The radius appears bowed and short. The radial head may be normal, dislocated, or fused to the humerus. The rays are often deficient or fused.

Diagnosis

Longitudinal deficiency of the fibula.

Pearls

Mild cases of fibular longitudinal deficiency are diagnosed by an unusually high-distal fibular physis.

As many as 1/3rd of patients with longitudinal deficiency of the radius have an accompanying syndrome.

US and MRI are useful for evaluating nonossified cartilaginous structures in PFFD.

Suggested Readings

- 439 Birch JG, Lincoln TL, Mack PW et al. Congenital fibular deficiency: a review of 30 years’ experience at one institution.. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2011; 93: 1144-1151 PubMed 21776551

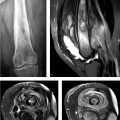

Case 129

Key Finding

Genu varum.

Top 3 Differential Diagnoses

Physiological bowing: Tibial bowing is a common normal developmental finding until the age of 2 years, but it does increase the risk of developing pathological tibia vara. It results from either intrauterine molding or delayed transition to normal mild genu valgus. Measurement depends on the tibiofemoral angle, which is the angle subtended by lines drawn longitudinally to the diaphyses. In infants, up to 16 to 20 degrees of varus angulation at the knee is normal, but by the age of around 3 years, this should change to 10 degrees valgus. Images show prominent but nonfragmented medial proximal tibial beaks. Distal femoral and proximal tibial medial epiphyses are wedge-shaped. Medial cortical thickening of femurs and tibias resolve as the bones straighten.

Blount disease (tibia vara): Obesity or early walking stresses the posteromedial proximal tibial metaphysis, leading to deformity of the epiphysis and physeal damage due to shearing stress. Like developmental bowing, this condition is more common in African Americans. Infantile Blount disease presents before the age of 4 years, whereas juvenile and adolescent forms manifest in older children, likely constituting later presentations of the same disease. Infantile Blount is defined by a tibial metaphyseal/diaphyseal angle of at least 16 degrees. Early cases show only metaphyseal beaking, but as disease progresses, the metaphysis becomes more irregular, depressed, and possibly fragmented. The tibia may subluxate laterally. Conservative treatment with orthoses is effective in mild cases of infantile Blount. Severe or delayed disease may be treated with realignment wedge osteotomy. MRI is primarily employed to evaluate formation of a medial physeal bar which, if present, mandates more complex surgery.

Rickets: Cartilage accumulates due to deficient growth plate cartilage and osteoid mineralization, leading to growth failure and osseous deformity. Nutritional vitamin D deficiency and X-linked hypophosphatemia are the most common underlying metabolic abnormalities. The growth plate widens due to disorganized, excessive cartilage. The metaphyses and metaphyseal equivalents of rapidly growing bones are most severely affected: wrist, knees, and anterior ribs. Insufficiency fractures, periosteal new bone, and bowing are seen in the diaphyses. Lower extremity bowing develops as children begin to stand. In addition to bowing, X-rays show physeal widening and metaphyseal flaring, cupping, and fraying.

Additional Diagnostic Consideration

Syndromic bowing: Metaphyseal chondrodysplasia, osteogenesis imperfecta, neurofibromatosis, and other syndromes may cause genu varum due to a variety of mechanisms.

Diagnosis

Blount disease.

Pearls

Genu varus up to 16 to 20 degrees is normal in children younger than 2 years of age.

Pathological tibia vara shows excess bowing in children under the ageof2 years or bowing that persists beyond the age of 2 years.

In Blount disease, metaphyseal beaking progresses to irregularity and, sometimes, fragmentation with lateral subluxation of the tibia.

Rickets, commonly due to nutritional vitamin D deficiency or X-linked hypophosphatemia, shows physeal widening, metaphyseal cupping and fraying along with insufficiency fractures and diaphyseal bowing.

Suggested Readings

- 441 Cheema JI, Grissom LE, Harcke HT. Radiographic characteristics of lower-extremity bowing in children.. Radiographics 2003; 23 (4) 871-880 PubMed 12853662

- 442 Ho-Fung V, Jaimes C, Delgado J, Davidson RS, Jaramillo D. MRI evaluation of the knee in children with infantile Blount disease: tibial and extra-tibial findings.. Pediatr Radiol 2013; 43 (10) 1316-1326 PubMed 23615630

- 443 Shore RM, Chesney RW. Rickets: Part I.. Pediatr Radiol 2013; 43 (2) 140-151 PubMed 23208530

- 444 Shore RM, Chesney RW. Rickets: Part II.. Pediatr Radiol 2013; 43 (2) 152-172 PubMed 23179485

Case 130

Key Finding

Lucent metaphyses.

Top 3 Differential Diagnoses

Leukemia: Acute leukemia is the most common pediatric malignancy, and acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) comprises the majority of cases. Radiographic abnormalities are seen in up to 2/3rd of patients at diagnosis. Metaphyseal lucencies are the most common finding and occur at sites of fastest growth, such as the knees, ankles, and wrists. Other findings include periosteal reaction, focal osteolytic lesions, osteopenia, and fractures. Compression fractures of the spine are common.

Osteomyelitis: Acute osteomyelitis is a significant cause of bone pathology in children, especially those under 5 years of age. Most cases occur due to hematogenous spread and involve the metaphyses. Scintigraphy and MRI are more sensitive than radiographs for early diagnosis. After about 10 days, radiographic findings such as ill-defined metaphyseal lucencies and periosteal bone formation may be seen.

Neuroblastoma: Neuroblastoma commonly metastasizes to bone. Children with skeletal metastases may complain of bone pain and arthritis-like symptoms. Radiographic appearance resembles that of other small, round blue cell tumors such as Ewing sarcoma and leukemia. There may be periosteal reaction, one or more lytic foci, lucent horizontal metaphyseal lines, and pathological fractures. MRI, positron emission tomographic (PET) CT, and metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) scans help assess for metastases.

Additional Diagnostic Considerations

TORSCH: TORSCH (toxoplasmosis, rubella, syphilis, cytomegalovirus [CMV], herpes) infections are acquired transplacentally and often affect the metaphyses. Syphilis and others may cause symmetrical lucent metaphyseal bands adjacent to a subphyseal dense band. Wimberger sign—symmetrical focal destruction of the medial proximal tibial metaphyses—is seen in about 50% of cases of congenital syphilis as well. Rubella classically leads to a “celery stalk” appearance with longitudinally arrayed linear striations extending from the epiphyses into the metaphyses. Other TORSCH infections may cause similar findings.

Rickets: Rickets is caused by vitamin D deficiency and leads to decreased mineralization of physeal cartilage. X-ray findings of physeal widening, loss of the zone of provisional calcification, metaphyseal fraying, and metaphyseal cupping are most evident at the fastest growing long bones (wrist and knee).

Scurvy: This lethal but treatable disease is caused by vitamin C deficiency. Radiographic findings include prominent zones of provisional calcification in the metaphyses (“white lines” of Frankel) with subjacent lines of demineralization (“scurvy lines”) and physeal widening.

Diagnosis

Congenital syphilis.

Pearls

Metaphyseal lucent bands are commonly seen with leukemia.

TORSCH infections may manifest metaphyseal lucency with a “celery-stalk” appearance.

Bony metastases are common in neuroblastoma and may show periosteal reaction, metaphyseal lucencies, lucent foci in other locations as well, and pathological fractures.

Suggested Readings

- 445 Blickman JG, van Die CE, de Rooy JW. Current imaging concepts in pediatric osteomyelitis.. Eur Radiol 2004; 14 (Suppl. Suppl 4) L55-L64 PubMed 14752569

- 446 Mostoufi-Moab S, Halton J. Bone morbidity in childhood leukemia: epidemiology, mechanisms, diagnosis, and treatment.. Curr Osteoporos Rep 2014; 12 (3) 300-312 PubMed 24986711

- 447 Ranson M. Imaging of pediatric musculoskeletal infection.. Semin Musculoskelet Radiol 2009; 13 (3) 277-299 PubMed 19724994

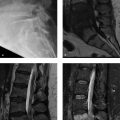

Case 131

Key Finding

Dense metaphyses.

Top 3 Differential Diagnoses

Physiological dense metaphyses: In healthy young children between the age of 2 to 6 years, increased metaphyseal density may be seen during periods of prolonged exposure to sunlight, especially common after winter. The exact mechanism is unknown, but this phenomenon may result from overproduction of endogenous vitamin D. Clues to diagnosis are that (1) at the knee, the proximal end of the fibula appears normal, with no dense band, and (2) the dense band is no more dense than the diaphyseal or metaphyseal cortex.

Lead toxicity (plumbism): Lead toxicity is most common between the ages of 1 and 3 years. It results from inhalation of lead dust or ingestion of contaminated water or fragments of lead paint. When serum lead levels exceed 50 micrograms/dL, excess lead impairs osteoclast function, leading to failure of bone resorption in the zone of provisional calcification. Bilateral, symmetrical, dense metaphyseal bands develop, which are typically denser than the cortex of the adjacent metaphysis or diaphysis. Such a band at the proximal end of the fibula is useful for diagnosis, since this area should be normal with physiological dense metaphyses. If high-lead levels persist, growth deformities, such as Erlenmeyer flask deformity, may develop. Other heavy metals have a similar effect. Although radiological findings are suggestive, diagnosis rests on laboratory tests.

Treated leukemia: After treatment for leukemia, the metaphyses may appear dense. However, children with leukemia more often demonstrate lucent metaphyses.

Additional Diagnostic Considerations

Healing rickets: Although patients with active rickets have frayed, flared, and cupped metaphyses with widening of the physis, healing bone shows dense juxtaphyseal–metaphyseal bands. This is most pronounced in the metaphyses or metaphyseal equivalents of rapidly growing bones: the wrists, knees, and anterior ribs.

Bisphosphonate therapy: Bisphosphanates treat patients with osteoporosis, usually due to osteogenesis imperfecta, steroid treatment, and neuromuscular disorders. These drugs increase bone density by inhibiting osteoclast-mediated bone resorption. Cyclical therapy leads to thin, dense metaphyseal lines that parallel the physis in long bones (“zebra stripes”) and a “bone within bone” appearance of the spine and flat bones.

Syphilis: In utero infection with Treponema pallidum may lead to bone abnormalities that manifest during the first 2 months of life. A dense sclerotic band may be positioned between the physis and the abnormally lucent metaphysis. About 50% of patients demonstrate the Wimberger sign, focal osteolysis of the medial proximal tibial metaphysis. Pathological fractures and periosteal new bone formation may be present as well. Patients may have a rash, hepatosplenomegaly, anemia, ascites, and nephrotic syndrome.

Diagnosis

Bisphosphonate therapy for underlying osteogenesis imperfecta.

Pearls

Physiological dense metaphyses appear no denser than adjacent cortex and spare the proximal fibula.

Although active rickets is characterized by wide, frayed metaphysis, during the treatment phase, the metaphyses may appear dense.

If lead levels exceed 50 micrograms/dL, dense metaphyseal bands may develop.

Infants with syphilis may show a dense band between the physis and the abnormally lucent metaphysis.

Suggested Readings

- 448 Raber SA. The dense metaphyseal band sign.. Radiology 1999; 211 (3) 773-774 PubMed 10352605

- 449 States LJ. Imaging of metabolic bone disease and marrow disorders in children.. Radiol Clin North Am 2001; 39 (4) 749-772 PubMed 11549169

Case 132

Key Finding

Dislocated hip.

Top 3 Differential Diagnoses

Developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH): DDH is most common in infants who are female, first-born, and/or with breech presentation or a family history of DDH or joint laxity. The Barlow maneuver attempts to displace the femoral head by pistoning the flexed hip. The Ortolani maneuver attempts to reduce a displaced hip by flexion and abduction. US is used for diagnosis until age 6 months, when ossification of the femoral head causes too much acoustic shadowing. The coronal view best depicts acetabular contour, with an “alpha angle” of 60 degrees or more considered normal. Transverse flexion views best depict femoral head motion within the acetabulum. In older children, the acetabulum and femoral head position are assessed on X-rays. Pavlik harness treatment is usually successful. Occasionally, casting is needed. Refractory DDH may be treated with acetabuloplasty to improve acetabular angle and coverage, along with femoral osteotomy to improve the position of the femoral head. Limited CT or MRI is then employed to assess hip position.

Neuromuscular disorder: The hip may subluxate and eventually dislocate in patients with cerebral palsy (CP) and other spastic neuromuscular conditions. With hyperactive adductor and iliopsoas muscles leading to persistent hip adduction, the acetabulum becomes oblique and shallow. Severe subluxation is common by the age of 7 years in patients with spastic CP. However, lateral coverage of the femoral head may be reduced for other reasons, such as disparity in size between the acetabulum (small) and femoral head (large), pelvic obliquity, adduction contracture, or femoral neck valgus/anteversion.

Trauma: A traumatic hemarthrosis may lead to posterolateral subluxation or, rarely, dislocation of the hip. In cases where the femoral head has not ossified, a Salter I fracture with lateral displacement of the distal fragment may mimic femoral head dislocation. This may be seen with nonaccidental trauma. Severe trauma, such as motor vehicle collision, may cause posterior dislocation of the femoral head.

Additional Diagnostic Consideration

Teratologic hip dysplasia: The incidence of hip dysplasia is increased with many skeletal dysplasias and syndromes. For example, as many as 5% of ambulatory children with Trisomy 21 have recurrent hip subluxation or dislocation. Patients with Ehlers–Danlos syndrome and Larsen syndrome also have an increased incidence of hip dislocation.

Diagnosis

Developmental dysplasia of the hip.

Pearls

DDH is most common in girls, first-borns, and among those with breech presentation and/or a family history of ligamentous laxity.

Hip US is most useful until the age of 6 months.

Patients with spastic CP have increased incidence of hip dislocation due to persistent hip adduction.

Before the femoral head ossifies, Salter I fracture of the proximal femoral physis with lateral displacement of the metaphysis, which may occur with nonaccidental trauma, mimics DDH.

Suggested Readings

- 450 Grissom LE. The pelvis and hip: Congenital and developmental conditions. In: Stein-Wexler R, Wootton-Gorges SL, Ozonoff MB, eds. Pediatric Orthopedic Imaging. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer; 2015

- 451 Hägglund G, Lauge-Pedersen H, Wagner P. Characteristics of children with hip displacement in cerebral palsy.. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2007; 8: 101 PubMed 17963501

- 452 Harcke HT. The role of ultrasound in diagnosis and management of developmental dysplasia of the hip.. Pediatr Radiol 1995; 25 (3) 225-227 PubMed 7644310

Case 133

Key Finding

Physeal widening.

Top 3 Differential Diagnoses

Salter–Harris type I fracture: This relatively uncommon fracture results from a shearing force that parallels the growth plate. It is most often seen in children younger than 5 years of age. Although transient displacement is common, the fracture usually reduces spontaneously before imaging, making diagnosis difficult. Comparison with the contralateral side may be helpful.

Slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE): This Salter–Harris I shearing fracture of the capital femoral physis is the most common hip problem of adolescence. It is more common in boys, African–Americans, and in overweight patients with mildly delayed skeletal maturation. Children with endocrinopathies, especially those with hypothyroidism or undergoing growth hormone therapy, are more likely to develop SCFE. SCFE is bilateral at presentation in about 10%, but up to 1/3rd will eventually develop SCFE in the contralateral hip. Patients present with limp and hip or knee pain. Those with “stable” SCFE can walk, whereas those with “unstable” SCFE cannot. The frontal neutral view shows physeal widening, a relatively short-appearing femoral head (due to rotation), and no femoral head projecting lateral to Klein’s line (drawn along the lateral femoral neck). The frog lateral view shows posteromedial offset of the femoral head with respect to the femoral neck. Sclerotic reactive bone, with posteromedial buttressing at the femoral neck, may be seen in subacute cases. Complications include chondrolysis, premature arthritis, pistol-grip deformity resulting in femoral-acetabular impingement, and limb-length discrepancy due to premature physeal closure.

Rickets: Rickets causes deficient resorption of the zone of provisional calcification. The disease results from lack of calcium absorption or overexcretion of phosphate. Patients may manifest bowing deformity or increased risk of fractures, including SCFE. X-rays may show fraying and cupping of the long bone metaphyses (most prominent at the knees and wrists), physeal widening, osteopenia with coarse trabeculae, bowing deformity, and insufficiency fractures. Flared and irregular anterior rib ends may result in the “rachitic rosary.” The metaphyseal fraying resolves with treatment, and metaphyses become unusually dense.

Additional Diagnostic Consideration

Osteomyelitis: Staphylococcus aureus is the most common pathogen for bone infection. From age 18 months until skeletal maturity, the metaphysis is most often affected due to localized sluggish blood flow. Radiographs may demonstrate cortical fraying and periosteal reaction, moth-eaten lucency of the bone, and associated soft-tissue swelling. Sometimes the physis becomes widened. MRI shows low-T1- and high-T2 signal within bone when radiographs are still normal.

Diagnosis

Slipped capital femoral epiphysis.

Pearls

SCFE is a Salter I fracture of the capital femoral physis.

Offset of the femoral head with respect to the neck is best diagnosed on a frog lateral view.

Rickets demonstrates metaphyseal fraying and cupping along with bowing deformity.

Osteomyelitis most often affects the metaphysis and demonstrates periostitis, moth-eaten lucency, and soft-tissue swelling.

Suggested Readings

- 453 Aronsson DD, Loder RT, Breur GJ, Weinstein SL. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis: current concepts.. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2006; 14 (12) 666-679 PubMed 17077339

- 454 Gill KG. Pediatric hip: pearls and pitfalls.. Semin Musculoskelet Radiol 2013; 17 (3) 328-338 PubMed 23787987

- 455 Jarrett DY, Matheney T, Kleinman PK. Imaging SCFE: diagnosis, treatment and complications.. Pediatr Radiol 2013; 43 (Suppl. Suppl 1) S71-S82 PubMed 23478922

Case 134

Clinical History

A 3-year-old boy with right hip pain that developed after an upper respiratory infection (Fig. 134‑1).

Key Finding

Hip effusion.

Top 3 Differential Diagnoses

Toxic synovitis: Toxic synovitis is the most common atraumatic cause of hip pain in young children. Most patients are between 3 and 8 years of age, and many cases are preceded by an upper respiratory infection. Joint fluid is present, which is better demonstrated with US than radiography. Treatment is supportive, and symptoms should resolve within 2 weeks. Avascular necrosis may develop in 1 to 2% of cases.

Septic arthritis: This usually affects the hip or knee of young children. Common causative organisms are Gram positive cocci, especially Staphylococcus aureus and various Streptococci. Septic arthritis is an orthopedic emergency, as delay in diagnosis may lead to articular cartilage destruction, osteonecrosis, impaired growth, and deformity. US is useful for diagnosing joint effusions prior to arthrocentesis. MRI findings of bone marrow edema, soft-tissue edema, and decreased femoral head enhancement are more prevalent in septic arthritis than toxic synovitis. Contrast-enhanced MRI demonstrates drainable fluid collections and appropriate sites for bone biopsy. Osteomyelitis may accompany septic arthritis.

Trauma: Joint effusions in the setting of trauma often result from fracture. However, patients with septic arthritis or toxic synovitis may present with a history of trauma, so these diagnoses must also be entertained.

Additional Differential Diagnoses

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA): JIA is a clinical diagnosis with varied manifestations. It encompasses all arthritides of unknown origin in patients less than 16 years of age and that last more than 6 weeks. Depending on disease stage, X-rays may show joint effusion, soft-tissue swelling, osteopenia, joint space narrowing, and erosions. MRI may show synovial thickening, joint effusion, marrow edema, erosions, and cartilage thinning.

Hemophilia: Hemophilia may be associated with recurrent bleeding into the joints with subsequent development of arthropathy. Arthropathy typically develops in the 1st and 2nd decades. The knee, ankle, elbow, and shoulder are most commonly affected. Radiographic findings in the acute phase include hemorrhagic joint effusion (hemarthrosis). On MRI, the hypertrophied synovial membrane appears dark on all sequences secondary to susceptibility artifact from hemosiderin. Erosions may eventually develop.

Pigmented villonodular synovitis (PVNS): PVNS represents the diffuse, intra-articular form of a spectrum of benign proliferative disorders that may affect the synovium, bursae, and tendon sheaths. PVNS occurs most often in the knee (80%), followed by hip, ankle, shoulder, and elbow. Peak presentation is in the 3rd and 4th decades. Radiographs may be normal or show periarticular soft-tissue swelling or erosions of the joint. MRI may show diffuse or nodular synovial thickening, with susceptibility artifact from hemosiderin.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree