Part 3 Genitourinary Imaging

Case 65

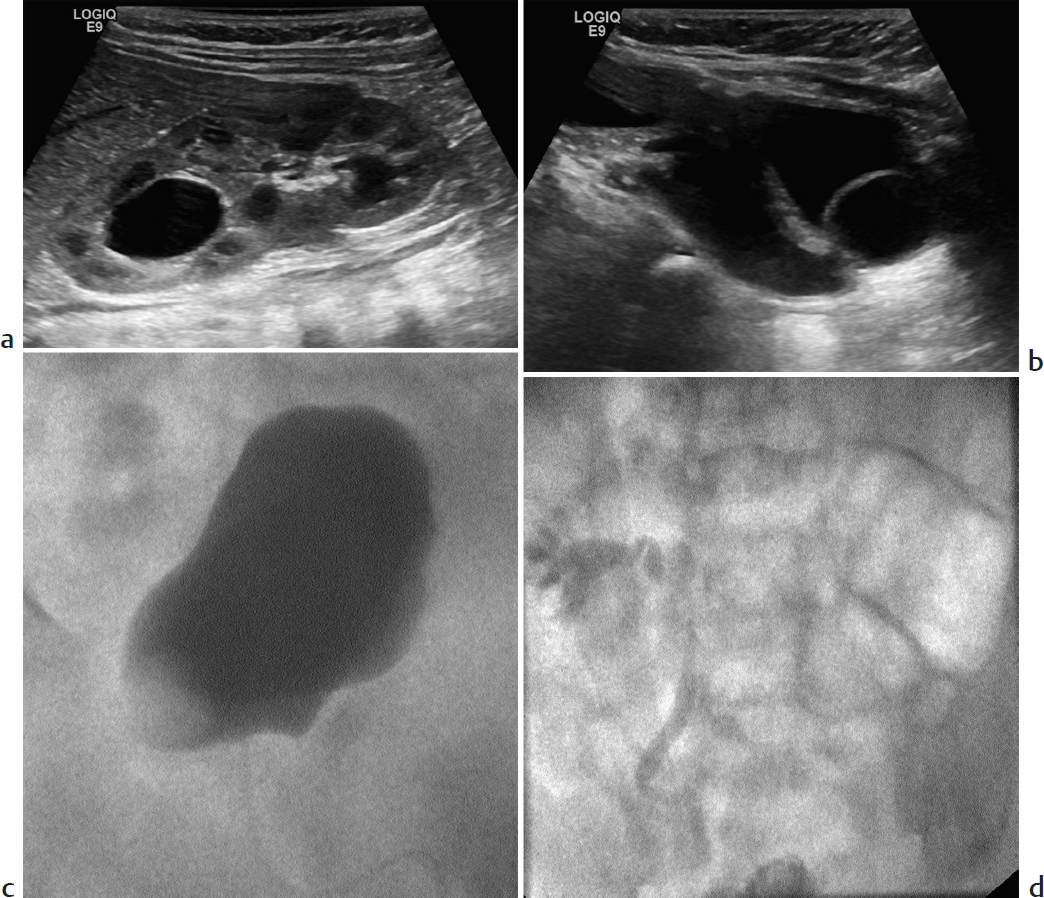

Key Imaging Finding

Suprarenal mass in a newborn.

Top Three Differential Diagnoses

Adrenal hemorrhage. Difficult labor, hypoxia, septicemia, and hemorrhagic disorders may cause a normal adrenal to hemorrhage in the perinatal period. Clinical manifestations include a palpable mass, anemia, jaundice, hypovolemic shock, and eventual adrenal insufficiency, but adrenal hemorrhage is occasionally diagnosed incidentally on renal US. It is more common on the right. The normal neonatal adrenal gland is relatively large and readily imaged by US, where it appears Y- or V-shaped with layers of hypoechoic cortex and thin echogenic medulla. With acute adrenal hemorrhage, the normal adrenal is replaced by a complex echogenic mass. As the hematoma evolves, the central portion becomes more hypoechoic and then completely cystic before eventual involution and subsequent calcification. This dynamic pattern of progressively decreasing echogenicity helps differentiate hemorrhage from other adrenal lesions.

Neuroblastoma (NB). NB derives from sympathetic ganglion cells of the neural crest and is the most common malignancy of infancy. In newborns, the origin is usually adrenal. On US, NB typically appears solid, heterogenous, and predominantly hyperechoic. Calcifications are common, contributing to diffuse increased echogenicity. Infrequently, the tumor appears cystic. NB shares imaging features with adrenal hemorrhage. On serial imaging, both lesions may decrease in size, since neonatal NB may involute. However, NB becomes more complex in appearance, whereas adrenal hemorrhage becomes more cystic. Neonatal NB may be widely metastatic but has an excellent prognosis that is not affected by the delay entailed by limited follow-up imaging. CT and MRI are useful for staging purposes. Urine catecholamines are often normal in neonatal NB, though elevated in older children with NB.

Intra-abdominal extralobar sequestration. Extralobar sequestration may occasionally be found in the abdomen, usually above the left kidney. Like extralobar sequestration elsewhere, it consists of nonfunctional bronchopulmonary tissue that is separate from the tracheobronchial tree and that has its own systemic arterial blood supply arising from the aorta, as well as venous drainage into the systemic system. The diagnosis of intra-abdominal extralobar sequestration is typically made on prenatal US as early as 16 weeks’ gestation. Characteristic imaging features include a solid, well-defined, triangular echogenic mass, usually just below the left diaphragm. It may have small cysts. The normal adrenal gland is visualized separate from the sequestration. Vascular supply may be shown by US, CT, or MRI.

Diagnosis

Adrenal hemorrhage.

Pearls

Gradual decrease in echogenicity helps differentiate hemorrhage from neuroblastoma.

Neonatal adrenal neuroblastoma has an excellent prognosis that is not affected by limited serial imaging.

Intra-abdominal extralobar pulmonary sequestration consists of nonfunctional bronchopulmonary tissue with systemic arterial blood supply, systemic venous drainage, and its own pleural covering.

Adrenal hemorrhage and neonatal neuroblastoma are often on the right, whereas sequestration is typically on the left.

Suggested Readings

Dhingsa R, Coakley FV, Albanese CT, Filly RA, Goldstein R. Prenatal sonography and MR imaging of pulmonary sequestration. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003; 180(2):433–437 Jordan E, Poder L, Courtier J, Sai V, Jung A, Coakley FV. Imaging of nontraumatic adrenal hemorrhage. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012; 199(1):W91–W98 Papaioannou G, McHugh K. Neuroblastoma in childhood: review and radiological findings. Cancer Imaging. 2005; 5:116–127 Yao W, Li K, Xiao X, Zheng S, Chen L. Neonatal suprarenal mass: differential diagnosis and treatment. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2013; 139(2):281–286Case 66

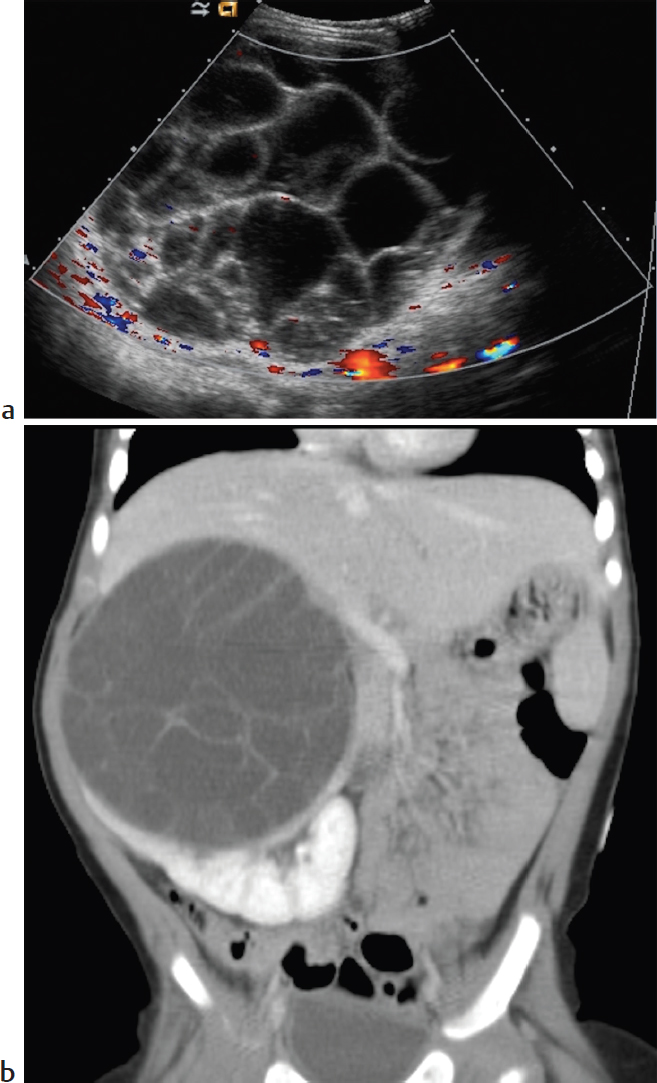

Key Imaging Finding

Suprarenal mass in a child.

Top Three Differential Diagnoses

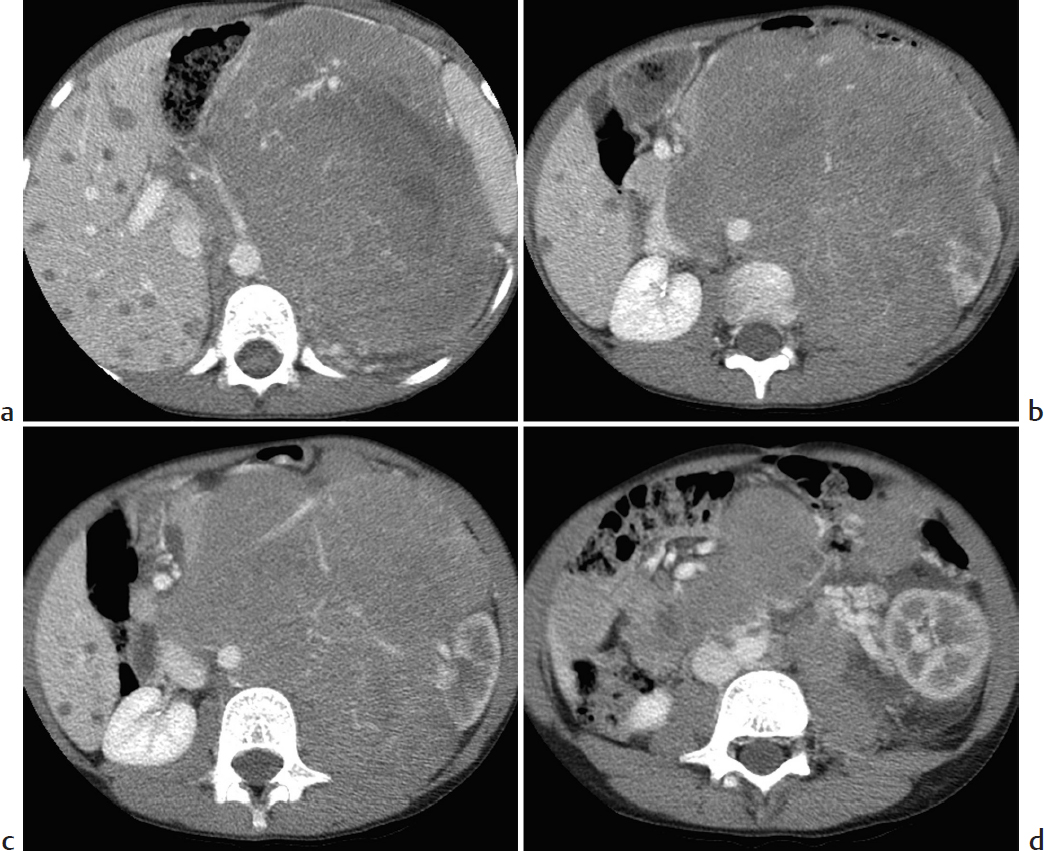

Neuroblastoma. Neuroblastoma is a malignant tumor of primitive neural crest cells. It accounts for approximately 10% of all pediatric neoplasms. Average age at diagnosis is approximately 2 years, and nearly all cases are diagnosed by age 10 years. Affected children are typically quite ill. They may present with paraneoplastic syndromes, such as profuse, watery diarrhea due to vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) secretion. The tumor may arise anywhere along the sympathetic chain, but it usually arises from the adrenal gland. Imaging features include an infiltrative soft-tissue mass that commonly calcifies, encases rather than invades vessels, and metastasizes to liver and bone.

Pheochromocytoma. Approximately 70% of pheochromocytomas arise from the adrenal gland. These tumors are rare in children, usually presenting with hypertension. Most occur spontaneously, but incidence is increased in patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) syndrome and von Hippel–Lindau syndrome. These tumors are usually metaiodobenzylguanidine avid and are classically very bright on T2-W MRI.

Extralobar sequestration. Although far more common in the lower lobes, sequestrations may occur below the diaphragm, usually above the left kidney. Always extralobar in this location, they drain into the systemic venous system. As with all sequestrations, arterial supply is directly from the aorta.

Additional Differential Diagnoses

Adrenal hemorrhage. In the perinatal period, adrenal hemorrhage is a significantly more common cause of a suprarenal mass than is neuroblastoma, but in the absence of trauma it is uncommon in older children. Classic US findings are a hypo- or anechoic, avascular suprarenal mass, although in the acute phase hemorrhage may appear complex. Serial imaging shows progressive decrease in size, often eventually leading to radiographically evident coarse calcification.

Adrenocortical carcinoma. Although a rare tumor of childhood, adrenocortical carcinomas are more common than simple adenomas. They are usually hormonally active. The tumors are typically greater than 5 cm in diameter at presentation. Internal necrosis and calcification are common, yielding an irregular, heterogeneous mass.

Renal or hepatic mass. Determining whether a suprarenal mass is adrenal, exophytic renal, or hepatic may be difficult, especially on axial imaging. Coronal and sagittal CT/MRI is helpful. Wilms tumor is the most common renal tumor, except in the neonatal period, when mesoblastic nephroma is encountered most often. Younger patients are more likely to have infantile hepatic hemangioma or hepatoblastoma, whereas hepatocellular carcinoma is more common in older children.

Diagnosis

Adrenal neuroblastoma with hepatic metastases.

Pearls

Neuroblastoma often calcifies, encases vessels, and metastasizes to liver and bone.

Adrenal hemorrhage is common in the perinatal period and decreases in size over time.

Pediatric pheochromocytomas are most common in children with underlying syndromes.

Suggested Readings

Balassy C, Navarro OM, Daneman A. Adrenal masses in children. Radiol Clin North Am. 2011; 49(4):711–727, vi Nour-Eldin NE, Abdelmonem O, Tawfik AM, et al. Pediatric primary and metastatic neuroblastoma: MRI findings: pictorial review. Magn Reson Imaging. 2012; 30(7):893–906 Paterson A. Adrenal pathology in childhood: a spectrum of disease. Eur Radiol. 2002; 12(10):2491–2508Case 67

Key Imaging Finding

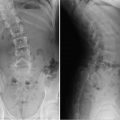

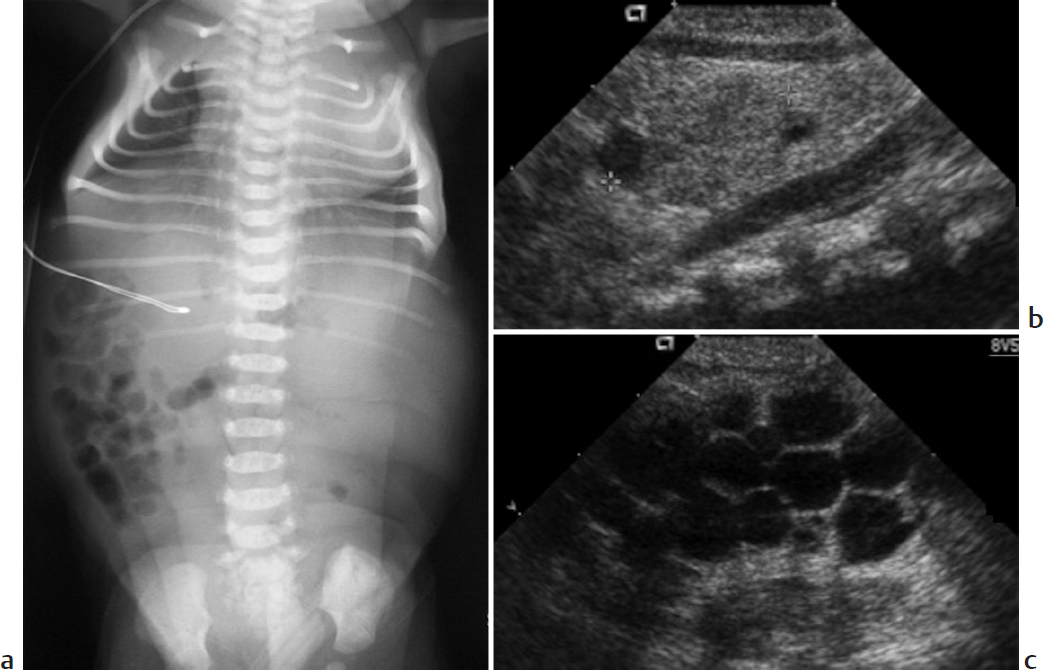

Pulmonary hypoplasia secondary to oligohydramnios.

Top Three Differential Diagnoses

Bilateral multicystic dysplastic kidneys (MCDK). MCDK is thought to result from intrauterine obstruction of the fetal renal collecting system or altered induction of renal tissue due to an abnormal ureteropelvic junction. US findings include multiple cysts of varying sizes that do not communicate with one another, along with echogenic, dysplastic-appearing intervening parenchyma. Renal size varies. Bilateral MCDK causes anuria and extreme oligohydramnios, leading to bilateral pulmonary hypoplasia, facial compression, and limb malformations (Potter sequence). The condition is fatal.

Bilateral renal agenesis. Bilateral renal agenesis is most common if at least one parent has unilateral renal agenesis or a renal anomaly. It too causes Potter sequence.

Severe bladder outlet obstruction. Posterior urethral valves (PUV) are the most common cause of congenital urethral obstruction. They occur only in boys. Wolffian duct tissue forms a thick, valvelike membrane that courses from the verumontanum to the distal prostatic urethra. Voiding cystourethrography (VCUG) demonstrates a dilated and elongated prostatic urethra that balloons above abrupt narrowing at the external sphincter. The bladder is often thick walled and trabeculated. Severe unilateral or bilateral hydroureteronephrosis is often seen. There may be renal cysts, and parenchyma may appear heterogeneous and echogenic due to cystic dysplasia. In utero oligohydramnios, hydronephrosis, bladder distension, and sometimes urinary ascites lead to prenatal diagnosis. Severe cases may demonstrate typical findings of Potter sequence.

Additional Differential Diagnosis

Autosomal-recessive polycystic kidney disease (ARPKD). About half of the cases of ARPKD are diagnosed prenatally with severe renal disease and oligohydramnios that may lead to pulmonary hypoplasia. Perinatal US shows massively enlarged, echogenic kidneys that lack normal corticomedullary differentiation; there may also be rosettes of tiny, dilated tubular ducts. Renal involvement is generally less severe in cases presenting later in childhood, when hepatic pathology dominates.

Diagnosis

Potter sequence with multicystic dysplastic kidneys.

Pearls

Intrauterine renal obstruction or altered induction of renal tissue leads to multicystic dysplastic kidney.

Posterior urethral valves usually lead to a dilated prostatic urethra, bladder wall thickening, and severe hydroureteronephrosis.

Renal cystic dysplasia may accompany posterior urethral valves.

Extreme oligohydramnios due to a variety of causes results in Potter sequence: bilateral pulmonary hypoplasia, facial compression, and limb malformations.

Suggested Readings

Avni FE, Hall M. Renal cystic diseases in children: new concepts. Pediatr Radiol. 2010; 40(6):939–946 Berrocal T, López-Pereira P, Arjonilla A, Gutiérrez J. Anomalies of the distal ureter, bladder, and urethra in children: embryologic, radiologic, and pathologic features. Radiographics. 2002; 22(5):1139–1164Case 68

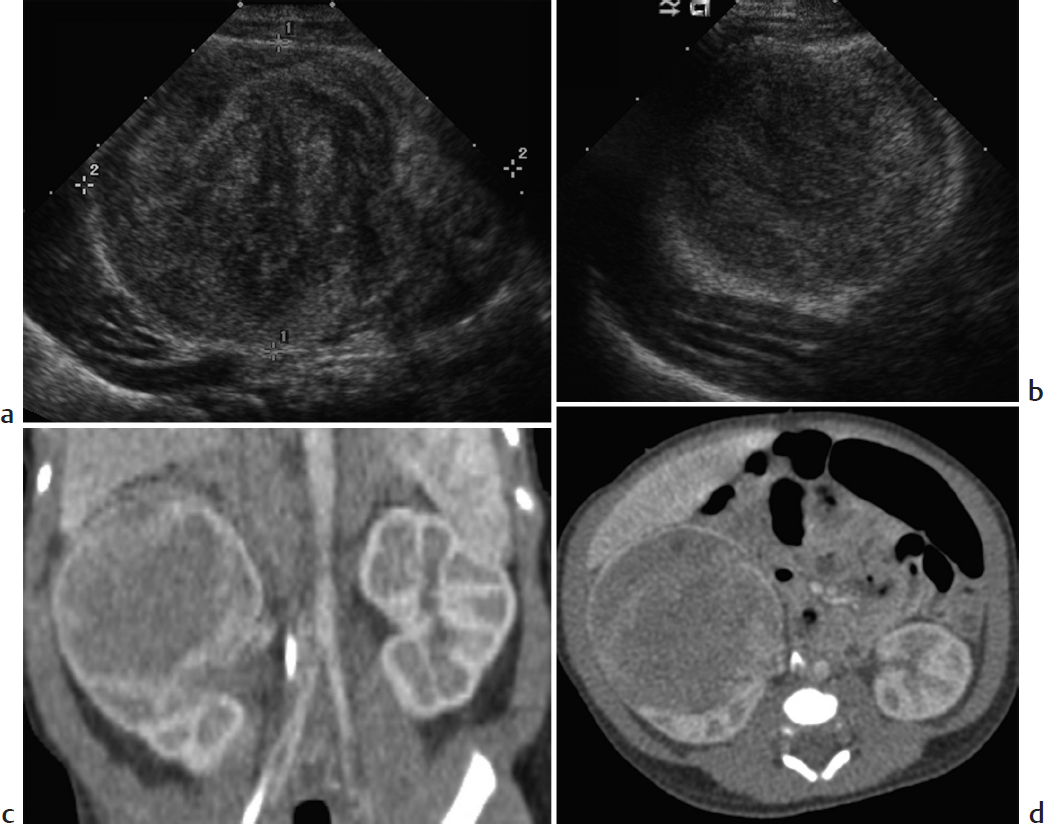

Key Imaging Finding

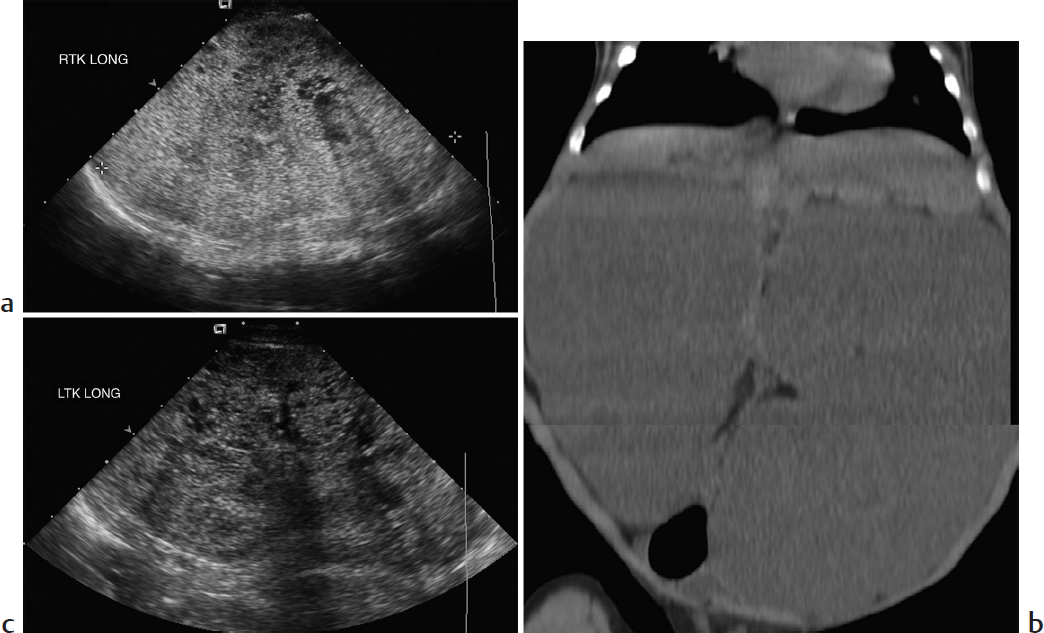

Bilateral nephromegaly.

Top Three Differential Diagnoses

Autosomal-recessive polycystic kidney disease (ARPKD). This ciliopathy leads to nonobstructive dilatation of the renal collecting ducts and portobiliary fibrosis. The extent of renal and hepatic involvement varies greatly. Mean age at presentation is 2.5 years, but about half of the cases are diagnosed prenatally with severe renal disease and oligohydramnios that may lead to pulmonary hypoplasia. Perinatal US shows massively enlarged, echogenic kidneys that lack normal corticomedullary differentiation; it may show rosettes of tiny, dilated tubular ducts. There may be a hypoechoic halo of normal, compressed cortex. At MRI, the kidneys are relatively T1-hypointense and T2-hyperintense; they demonstrate innumerable tiny tubular cystic foci and sometimes a few macrocysts. Renal involvement is generally less severe in cases presenting later in childhood, when hepatic findings dominate, including intrahepatic biliary ductal dilatation or cysts, relatively large left hepatic lobe, and eventual portal venous hypertension.

Lymphoma/leukemia. Lymphocytic leukemia may infiltrate the kidneys diffusely, causing renal enlargement. Corticomedullary differentiation is decreased, and cortical enhancement reduced. Non-Hodgkin Burkitt lymphoma is the most common lymphoma to affect the kidneys. Renal involvement usually results from either hematogenous spread or direct extension. There may be multiple bilateral soft-tissue nodules, a solitary mass, or diffuse nephromegaly.

Meckel–Gruber syndrome. This perinatally lethal disorder typically presents with cystic renal dysplasia, postaxial polydactyly, and occipital encephalocele. It may be diagnosed in utero, during the late first or early second trimester (earlier than ARPKD). The medullary pyramids appear enlarged and hypoechoic.

Additional Differential Diagnoses

Bilateral multicystic dysplastic kidneys (MCDK). MCDK is thought to result from intrauterine obstruction of the fetal renal collecting system or altered induction of renal tissue due to an abnormal ureteropelvic junction. US findings include multiple cysts of varying sizes that do not communicate with one another, along with echogenic, dysplastic-appearing intervening parenchyma. Renal size varies. Bilateral MCDK leads to intrauterine Potter sequence due to anuria and severe oligohydramnios.

Autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD). This usually presents in older children but is occasionally encountered in infants and young children with enlarged, echogenic kidneys that mimic ARPKD. However, high-resolution US shows round cysts, rather than the tiny tubular cysts of ARPKD, and the cortex is not spared. Cysts are also common in the liver, spleen, pancreas, and seminal vesicles. ADPKD is the most common inherited cause of end-stage renal disease.

Diagnosis

Autosomal-recessive polycystic kidney disease.

Pearls

Kidneys affected by autosomal-recessive polycystic kidney disease are enlarged and diffusely echogenic, with mostly medullary tubular cysts.

Hepatic disease predominates in autosomal-recessive polycystic kidney disease presenting in older children.

Renal lymphoma appears as multiple nodules, a solitary mass, or diffuse nephromegaly.

Autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease may mimic autosomal-recessive polycystic kidney disease but cysts are usually larger, round, and both cortical and medullary.

Suggested Readings

Avni FE, Hall M. Renal cystic diseases in children: new concepts. Pediatr Radiol. 2010; 40(6):939–946 Chung EM, Conran RM, Schroeder JW, Rohena-Quinquilla IR, Rooks VJ. From the radiologic pathology archives: pediatric polycystic kidney disease and other ciliopathies: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2014; 34(1):155–178 Lee EY. CT imaging of mass-like renal lesions in children. Pediatr Radiol. 2007; 37(9):896–907Case 69

Clinical Presentation

A 16-year-old boy with abdominal pain after a motor vehicle crash (▶Fig. 69.1).

Key Imaging Finding

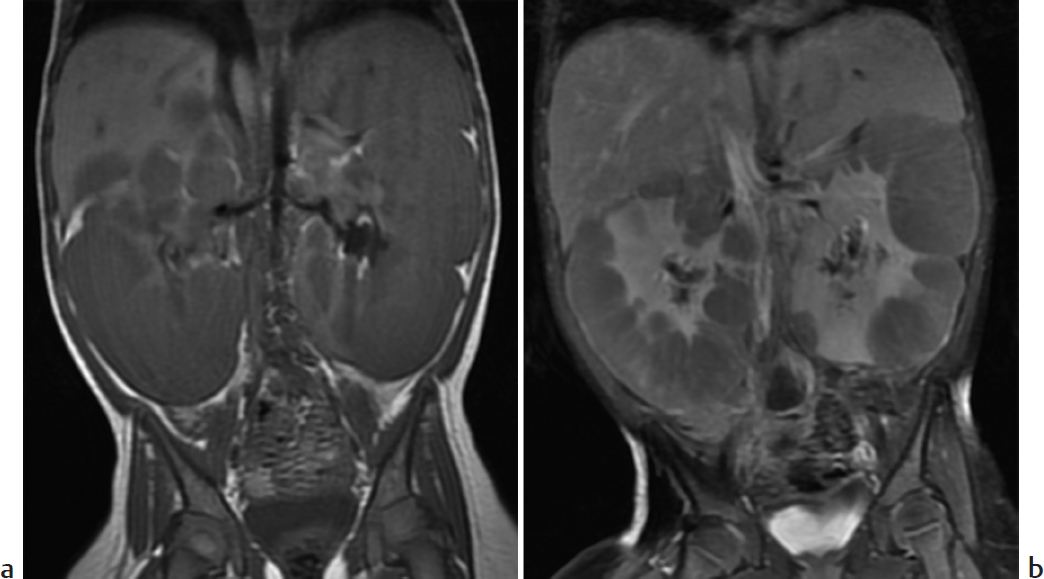

Multiple bilateral renal cysts.

Top Three Differential Diagnoses

Autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD). This common inherited disease usually presents in adulthood, when cysts have replaced renal parenchyma and patients develop hypertension and renal failure. Less than 2% present before the age of 15 years. Diagnosis during childhood is usually serendipitous or due to family history. Kidneys are normal to slightly enlarged. Cysts are seen throughout the nephron, not sparing the cortex, and they are round rather than tubular (unlike autosomal-recessive polycystic kidney disease [ARPKD]). If even one cyst is seen in a genetically predisposed child, ADPKD is likely; three cysts establish the diagnosis. When encountered in infants and very young children, kidneys usually appear large and echogenic, mimicking ARPKD, but tiny round macrocysts may be evident. Cysts are also common in the liver, spleen, pancreas, and seminal vesicles. Brain aneurysms occur in about 10%. The gene for ADPKD is adjacent to one of the genes for tuberous sclerosis, so patients may manifest features of both diseases.

Tuberous sclerosis. This systemic autosomal-dominant disorder is characterized by multiple hamartomas in the brain, skin, kidneys, eye, heart, and elsewhere; renal cysts; and—rarely—renal cell carcinoma. Angiomyolipomas are the most common renal lesion in this disease, often appearing before the age of 10 years. These lesions are echogenic, usually small, and typically located in the renal cortex. They tend to enlarge and may bleed. Renal cysts predominate in the infant, but overall occur less often and are less numerous.

von Hippel–Lindau (VHL) syndrome. A mutation of the VHL tumor suppressor gene causes increased angiogenesis in this disorder. Tumors develop in multiple organs, including hemangioblastoma (especially common in the retina and cerebellum), clear cell renal carcinoma (RCC), renal angiomyolipoma, adrenal pheochromocytoma, and islet cell tumors. Pancreatic and renal cysts also occur. RCC is seen as early as the age of 3 years in these children. It is likely to be mixed solid/cystic, multicentric, and bilateral.

Additional Differential Diagnoses

Bilateral simple renal cysts. Simple renal cysts are relatively rare in children and may be the first sign of renal cystic disease. Especially if more than one cyst is present, follow-up is suggested to assess for enlargement or development of additional cysts, which would suggest cystic kidney disease.

ARPKD. This condition usually manifests in infancy with enlarged, echogenic kidneys. However, in older children with relatively more liver disease, it may manifest as single or multiple cysts.

Diagnosis

Autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease.

Pearls

In genetically predisposed patients, the presence of three or more renal cysts indicates autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease.

The renal cysts of autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease are round and distributed throughout the kidney, unlike autosomal-recessive polycystic kidney disease, which has tubular cysts that generally spare the cortex.

Renal angiomyolipomas are more common than renal cysts in patients with tuberous sclerosis.

Simple renal cysts may be the first sign of renal cystic disease in children and should be followed.

Suggested Readings

Avni FE, Hall M. Renal cystic diseases in children: new concepts. Pediatr Radiol. 2010; 40(6):939–946 Chung EM, Conran RM, Schroeder JW, Rohena-Quinquilla IR, Rooks VJ. From the radiologic pathology archives: pediatric polycystic kidney disease and other ciliopathies: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2014; 34(1):155–178 Monsalve J, Kapur J, Malkin D, Babyn PS. Imaging of cancer predisposition syndromes in children. Radiographics. 2011; 31(1):263–280 Winterkorn EB, Daouk GH, Anupindi S, Thiele EA. Tuberous sclerosis complex and renal angiomyolipoma: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Nephrol. 2006; 21(8):1189–1193Case 70

Key Imaging Finding

Multiple renal masses.

Top Three Differential Diagnoses

Multifocal pyelonephritis. This usually results from ascending infection. Lesions are often ill-defined and, if due to reflux, more common in upper and lower poles. US appearance varies and is often normal. CT and MRI may show hypoenhancing masses or patchy striations extending to the periphery.

Lymphoma/leukemia. Renal lymphoma typically occurs in the setting of multiorgan involvement by non-Hodgkin lymphoma, especially Burkitt. The most common appearance is multiple parenchymal masses, leading to renal enlargement. More unusual manifestations include renal infiltration, a single intrarenal mass, or an invasive extrarenal mass. Lesions are hypoechoic at US and show little enhancement at CT and MRI. Renal leukemia appears as relatively homogeneous renal enlargement.

Tuberous sclerosis (TS). This systemic autosomal-dominant disorder is characterized by multiple hamartomas. About 80% of children will develop angiomyolipomas (AMLs) in the brain, skin, kidneys, eye, heart, and elsewhere. Renal cysts and (rarely) renal cell carcinoma also occur. AMLs contain varying amounts of fat, abnormal vessels, and smooth muscle. In TS, these benign tumors occur at an earlier age and are likely to be large, multiple, and bilateral, increasing in size around puberty. AMLs in normal children are usually single. Catastrophic hemorrhage, usually in tumors greater than 4 cm, may be fatal and is potentially prevented by prophylactic embolization. AMLs are echogenic on US. The fat in small lesions is easier to characterize at CT/MRI, where they show fat attenuation/signal. Wilms tumor, lipoma, and teratoma may also contain fat.

Additional Differential Diagnoses

Nephroblastomatosis. Multifocal or diffuse islands of primitive blastemal tissue after 36 weeks’ EGA result in nephroblastomatosis. The lesions may be single or multiple. Strongly associated with Wilms tumor, nephroblastomatosis is seen in 40% of patients with unilateral Wilms tumor and almost all of those with synchronous or metachronous disease. Nephroblastomatosis occurs in a variety of syndromes, including Beckwith–Wiedemann, trisomy 18, sporadic aniridia, Denys–Drash and WAGR (Wilms tumor, aniridia, genitourinary anomalies, mental retardation). Up to 5% of patients with nephroblastomatosis will develop Wilms tumor. Kidneys may be enlarged, and US shows indistinct corticomedullary differentiation and sometimes focal hypoechoic areas. The lesions are homogeneous at CT and do not enhance. Although prior to administration of contrast nephroblastomatosis may be heterogeneous at MRI, with gadolinium it appears more uniform than Wilms tumor.

Wilms tumor. Although usually isolated, Wilms tumor may present with multiple masses (“synchronous”).

Diagnosis

Nephroblastomatosis.

Pearls

Angiomyolipomas are common in children with tuberous sclerosis and more likely to be multiple, bilateral, and large.

Angiomyolipomas larger than 4 cm are at increased risk for catastrophic hemorrhage.

Renal lymphoma most often appears as multiple bilateral masses but may also appear as diffuse infiltration or a focal mass.

Nephroblastomatosis is strongly associated with Wilms tumor, especially if Wilms tumor is multifocal.

Suggested Readings

Gee MS, Bittman M, Epelman M, Vargas SO, Lee EY. Magnetic resonance imaging of the pediatric kidney: benign and malignant masses. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 2013; 21(4):697–715 Geller E, Kochan PS. Renal neoplasms of childhood. Radiol Clin North Am. 2011; 49(4):689–709, vi Lowe LH, Isuani BH, Heller RM, et al. Pediatric renal masses: Wilms tumor and beyond. Radiographics. 2000; 20(6):1585–1603 Siegel MJ, Chung EM. Wilms’ tumor and other pediatric renal masses. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 2008; 16(3):479–497, viCase 71

Key Imaging Finding

Cystic upper pole of the kidney.

Top Three Differential Diagnoses

Duplex kidney with upper pole hydronephrosis. Duplex collecting systems are relatively common, encountered in about 10% of children with UTI. According to the Weigert–Meyer rule, the upper pole ureter inserts ectopically, inferomedial to the normal position; the collecting system is more likely to obstruct and to terminate in a ureterocele. The lower pole collecting system is more likely to reflux. Therefore, either or both collecting systems may be dilated. The lower pole of a duplex system has relatively few calyces. Hence, the configuration of the contrast-filled lower pole calyces suggests a “drooping lily.”

Segmental multicystic dysplastic kidney (MCDK). Sometimes part of the kidney is normal, and only a portion is affected by multicystic dysplasia. Furthermore, multicystic dysplasia may affect a portion of a duplex kidney, suggested by the presence of a ureterocele. The presence of dysplastic, echogenic parenchyma helps with the diagnosis, but sometimes functional renal nuclear imaging is required to differentiate between a large cyst due to upper pole hydronephrosis (which will show activity) and segmental MCDK (which will not).

Cystic renal mass. Multilocular cystic nephroma is a rare entity that affects young males and older adult females. Patients present with a multiloculated cystic renal mass that characteristically herniates into the renal pelvis/collecting system. Wilms tumor is more common, but, although there is often central necrosis and hemorrhage, Wilms tumor is rarely purely cystic. Similarly, mesoblastic nephroma and clear cell renal carcinoma are rarely completely cystic.

Additional Differential Diagnoses

Renal cyst. Simple cysts are uncommon in children. Three or more may indicate the presence of cystic renal disease.

Cystic adrenal mass. Occasionally, it is difficult to differentiate a suprarenal adrenal mass from an upper pole renal mass, although clarification is almost always possible with coronal or sagittal CT or MRI. Depending on its phase of evolution, adrenal hemorrhage may appear cystic. Although neuroblastoma is usually solid and often partly calcified, it may be cystic when presenting in the perinatal period.

Diagnosis

Vesicoureteral reflux into the lower pole of the kidney with associated ureterocele and hydroureter.

Pearls

According to the Weigert–Meyer rule, the upper pole ureter inserts ectopically inferomedial to its normal position, may be obstructed, and may terminate in a ureterocele.

Reflux is more common in the lower pole of a duplex system.

Segmental multicystic dysplasia may develop in a normal kidney or in part of a duplex kidney.

Wilms tumor may be hemorrhagic and necrotic, but it is rarely purely cystic.

Suggested Readings

Avni FE, Hall M. Renal cystic diseases in children: new concepts. Pediatr Radiol. 2010; 40(6):939–946 Muller LS. Ultrasound of the paediatric urogenital tract. Eur J Radiol. 2014; 83(9):1538–1548Case 72

Clinical Presentation

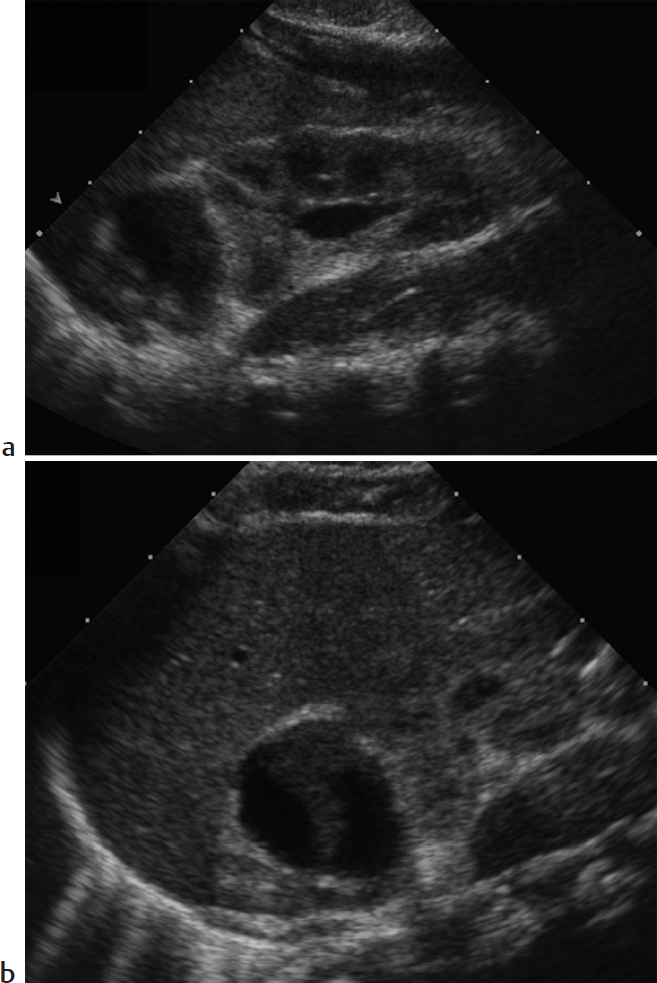

A 10-month-old with a right-sided palpable abdominal mass on routine physical examination (▶Fig. 72.1).

Key Imaging Finding

Unilateral cystic renal mass.

Top Three Differential Diagnoses

Hydronephrosis. Hydronephrosis is the most common cause of a renal mass in a child. Unilateral disease is most often due to ureteropelvic junction (UPJ) obstruction or extrinsic compression on the ureter. Bilateral hydronephrosis is usually due to bladder outlet obstruction (posterior urethral valves in boys). On US, the cystic lesions, which are the dilated collecting system, communicate centrally at the renal pelvis, a key distinguishing feature.

Multicystic dysplastic kidney (MCDK). MCDK is thought to result from intrauterine obstruction of the fetal renal collecting system or altered induction of renal tissue due to an abnormal UPJ. US findings include multiple cysts of varying sizes that do not communicate with one another. The affected renal segment is nonfunctioning. The other kidney should be closely evaluated, since contralateral anomalies, such as UPJ obstruction, are common.

Multilocular cystic nephroma. This rare entity has a bimodal age distribution and affects young males and older adult females. Patients present with a multiloculated cystic renal mass that characteristically herniates into the renal pelvis/collecting system. Septations within the lesion may enhance on CT. The tumor is surgically resected.

Additional Differential Diagnoses

Cystic Wilms tumor. Wilms tumor is the most common renal malignancy of childhood, with a peak incidence of age 3 years. Patients typically have a large abdominal mass that is solid and heterogeneous, but especially in infants Wilms tumor may be cystic. Rarely, both kidneys are involved. Local spread includes the renal vein, inferior vena cava, and lymph nodes. Unlike neuroblastoma, Wilms tumor invades vessels rather than encasing them. It usually metastasizes to the lungs and liver. The tumor is typically sporadic but may be associated with cryptorchidism, hemihypertrophy, aniridia, Denys–Drash, and other syndromes.

Renal abscess. Renal abscesses are rare but serious complications of UTIs. They usually occur in children with chronic infections from persistent vesicoureteral reflux. US shows an ill-defined hypoechoic region, usually at the corticomedullary junction. Abscesses are hypoechoic on US and hypodense on CT.

Diagnosis

Multilocular cystic nephroma.

Pearls

Hydronephrosis is the most common cause of a renal mass in childhood.

Multicystic dysplastic kidney consists of multiple noncommunicating cysts; incidence of contralateral anomalies is increased.

Multilocular cystic nephroma has a bimodal age distribution and typically herniates into the renal pelvis.

Wilms tumor, the commonest renal malignancy of childhood, may occasionally be cystic, especially in infants.

Suggested Readings

Avni FE, Hall M. Renal cystic diseases in children: new concepts. Pediatr Radiol. 2010; 40(6):939–946 Chung EM, Conran RM, Schroeder JW, Rohena-Quinquilla IR, Rooks VJ. From the radiologic pathology archives: pediatric polycystic kidney disease and other ciliopathies: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2014; 34(1):155–178 Lowe LH, Isuani BH, Heller RM, et al. Pediatric renal masses: Wilms tumor and beyond. Radiographics. 2000; 20(6):1585–1603Case 73

Key Imaging Finding

Solid renal mass in a young infant.

Top Three Differential Diagnoses

Mesoblastic nephroma. Mesoblastic nephroma is a hamartomatous tumor of the kidney and is the most common solid renal mass in neonates. Mean age at presentation is 2 months. Patients are typically asymptomatic except for a palpable mass, although they may have hypercalcemia. Since imaging findings of mesoblastic nephroma are indistinguishable from Wilms tumor, it must be resected.

Wilms tumor. Wilms tumor is the most common renal malignancy of childhood, with peak incidence at age 3 years. After age 2 months, it is the most common renal mass in infants. Tumors usually present as an asymptomatic abdominal mass. They are typically well defined and round, arising from the renal cortex. When large, they may appear heterogeneous and partly cystic, with internal necrosis and hemorrhage. Calcification is relatively uncommon, and intratumoral fat is extremely rare. Wilms tumor spreads locally through the ipsilateral renal vein, via lymphatics to local lymph nodes, and hematogenously to the lungs and liver. Bilateral disease is seen in about 5% of patients, more common in those with nephroblastomatosis or associated congenital anomalies such as cryptorchidism, hypospadias, horseshoe kidney, hemihypertrophy, and aniridia. Incidence is increased with numerous syndromes.

Rhabdoid tumor. This very aggressive renal malignancy usually occurs before age 2 years and presents with hematuria or fever. Increased parathormone levels may cause hypercalcemia, leading to medullary nephrocalcinosis in the contralateral kidney. The tumor is usually at least 9 cm at presentation. In general, it resembles Wilms tumor. However, rhabdoid tumor is more central than Wilms tumor, arising from the medulla and often involving the hilum. Subcapsular fluid collections are more common than with Wilms tumor. Lung and liver metastases are common, but the tumor also spreads to bone and brain. There is an increased incidence of posterior fossa medulloblastoma and primitive neuroectodermal tumor, as well as other CNS tumors. Mortality is about 75%.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree