Part 6: Infection

Case 85

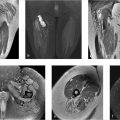

Key Finding

Penumbra sign.

Top 3 Differential Diagnoses

Subacute osteomyelitis: Unlike acute infection that commonly presents with overt clinical and laboratory findings, subacute and chronic infections may only present with pain, nonspecific inflammatory markers (e.g., elevated C-reactive protein), and nonspecific radiographic findings.

MRI can be helpful in differentiating infection from neoplasm when a penumbra sign is present. The penumbra sign is a thin layer of granulation tissue that rims an abscess and is characteristically seen with subacute osteomyelitis. For subacute osteomyelitis, the reported diagnostic sensitivity and specificity of the penumbra sign are approximately 75% and >90%, respectively. The penumbra sign may also be associated with chronic osteomyelitis, soft-tissue abscess, and “acute on chronic” musculoskeletal infections.

The penumbra sign is reported most frequently in the metaphysis and metadiaphysis of long bones. The “penumbra” (halo) of increased signal on unenhanced T1 images (hyperintense to the abscess and isointense to normal muscle) may be caused by high-protein content within granulation tissue, which can be easily overlooked. If contrast is administered intravenously, this rim of vascularized, inflamed granulation tissue around the abscess enhances avidly.

Subchondral ganglion/cyst: Benign cystic-appearing lesions of bone, such as an intraosseous ganglion, can show findings reminiscent of a penumbra. Unlike most cases of osteomyelitis, subchondral cysts are commonly associated with overlying chondrosis and located in epiphyseal regions.

Tumors: Benign or malignant tumors may show findings interpreted as a penumbra sign. Specifically, reports have included cases of eosinophilic granuloma, chondroblastoma, leiomyosarcoma, and even Ewing sarcoma (in the presence of a bulky soft tissue mass). In some cases, this phenomenon of T1 hyperintensity may be due to a pathologic fracture with subacute hematoma.

Diagnosis

Subacute osteomyelitis.

Pearls

Musculoskeletal infection in the subacute and chronic setting can be difficult to differentiate from neoplasm, both with clinical evaluation and with imaging.

The penumbra sign is considered highly characteristic of musculoskeletal infection, most commonly subacute osteomyelitis.

The penumbra sign is a thin halo of relatively hyperintense signal on unenhanced T1 images caused by granulation tissue that rims an abscess.

Suggested Readings

- 276 Crundwell N, O’Donnell P, Saifuddin A. Non-neoplastic conditions presenting as soft-tissue tumours.. Clin Radiol 2007; 62 (1) 18-27 PubMed 17145259

- 277 Davies AM, Grimer R. The penumbra sign in subacute osteomyelitis.. Eur Radiol 2005; 15 (6) 1268-1270 PubMed 15300398

- 278 Kasalak Ö, Overbosch J, Adams HJ et al. Diagnostic value of MRI signs in differentiating Ewing sarcoma from osteomyelitis.. Acta Radiol 2019; 60 (2) 204-212 PubMed 29742917

- 279 McCarville MB, Chen JY, Coleman JL et al. Distinguishing osteomyelitis from Ewing sarcoma on radiography and MRI.. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2015; 205 (3) 640-650, quiz 651 PubMed 26295653

- 280 McGuinness B, Wilson N, Doyle AJ. The “penumbra sign” on T1-weighted MRI for differentiating musculoskeletal infection from tumour.. Skeletal Radiol 2007; 36 (5) 417-421 PubMed 17340164

- 281 Shimose S, Sugita T, Kubo T, Matsuo T, Nobuto H, Ochi M. Differential diagnosis between osteomyelitis and bone tumors.. Acta Radiol 2008; 49 (8) 928-933 PubMed 18615335

Case 86

Key Finding

Sequestrum.

Top 3 Differential Diagnoses

Osteomyelitis: A sequestrum in the setting of osteomyelitis refers to a segment of dead, sclerotic bone that is separated from living bone by granulation tissue. The sequestrum may reside within the marrow and become a source of focal infection that can cause repeated flare-ups of acute osteomyelitis. A rim of living bone that surrounds the sequestrum is referred to as an involucrum. The involucrum may be permeated by a cloaca through which pus and the sequestrum itself may be expelled to the skin surface through a draining sinus tract.

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH): Eosinophilic granuloma is a subset of LCH which is characterized by multiple, predominantly lytic lesions throughout the axial and appendicular skeleton of children and young adults (< 30 years of age). It accounts for approximately 70 percent of cases of LCH. Lesions within the long bones are characterized as lytic lesions with endosteal scalloping and occasionally periosteal reaction. Cranial involvement classically consists of a lytic lesion with beveled edges due to asymmetric involvement of the inner and outer tables. Lytic lesions of cranial vault sometimes contain a central and radiodense fragment of bone, referred to as “button sequestrum.”

Osteoid osteoma: The classic radiographic findings in an osteoid osteoma are a centrally located oval or round radiolucent nidus surrounded by a uniform region of sclerotic bone. The central lucency is highly vascularized and is the target of surgical debridement or radiofrequency ablation. In 80% of cases, the nidus contains variable amounts of calcification. Common sites include the long bones of the lower extremities and spine.

Additional Diagnostic Considerations

Lymphoma: Both Hodgkin and nonHodgkin lymphoma can affect the bones in both primary and widespread diseases. Primary nonHodgkin lymphoma most commonly presents in the appendicular skeleton as an aggressive osteolytic lesion with poorly defined margins. Osteosclerosis, when evident, is more commonly found in Hodgkin disease, which can present with osteolytic lesions, osteosclerotic lesions, or a mixture of both. Sequestrum is more commonly seen in the Hodgkin variant.

Fibrosarcoma: Fibrosarcomas are characterized by osteolytic foci with a geographic, moth-eaten, or permeative pattern of bone destruction. There is little osteosclerosis and a striking absence of a significant osseous reaction despite the bone destruction. Occasionally, a sequestrum may be evident.

Diagnosis

Osteomyelitis.

Pearls

Osteomyelitis may demonstrate a sequestrum surrounded by an involucrum and permeated by a cloaca.

LCH results in lytic calvarial lesions with beveled edges and button sequestrum.

Osteoid osteomas typically demonstrate a round or oval radiolucent nidus surrounded by sclerotic bone.

The central nidus in osteoid osteoma is highly vascularized and is the target of radiofrequency ablation.

Suggested Readings

- 283 Jennin F, Bousson V, Parlier C, Jomaah N, Khanine V, Laredo JD. Bony sequestrum: a radiologic review.. Skeletal Radiol 2011; 40 (8) 963-975 PubMed 20571796

- 284 Krasnokutsky MV. The button sequestrum sign.. Radiology 2005; 236 (3) 1026-1027 PubMed 16118175

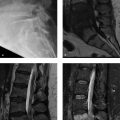

Case 87

Clinical History

A young adult man presented to the emergency department with thigh pain (Fig. 87‑1).

Key Finding

Abscesses in bone and adjacent to bone, with thin perforations in cortex–Roentgen classic.

Diagnosis

Infection: Musculoskeletal infections can have protean imaging manifestations. The imaging findings may vary according to infection acuity (acute, subacute, or chronic), patient age, route of bone contamination (i.e., hematogenous, contiguous spread, or direct contamination), and infectious organism.

Given that the presentation of musculoskeletal infection can vary significantly, depending on the duration, location, and cause, it is prudent to synthesize all pertinent data for an accurate diagnosis, including clinical history, laboratory results, and radiographic/imaging findings.

MRI is generally considered sensitive for the detection of early osteomyelitis. Diagnostic specificity of MRI, however, may be limited; diminished T1 and increased T2 signal intensity in bone marrow can be caused by a wide variety of etiologies.

Although MRI signal intensity changes are often not specific for osteomyelitis, some imaging findings should be recognized as highly characteristic. In particular, with hematogenous seeding of osteomyelitis in a long bone, a peripherally enhancing abscess in the medullary bone can be accompanied by cortical perforation and abscess formation overlying the cortex (under the periosteum in children or in the adjacent soft tissue in adults). With contiguous spread of infection (classically seen in the diabetic foot), a soft-tissue defect may abut the bone and be associated with cortical disruption and underlying marrow changes.

Diagnosis

Osteomyelitis with cloaca and abscesses (intraosseous and soft tissue).

Pearls

For the diagnosis of osteomyelitis, MRI is highly sensitive and sometimes specific. The specificity of MRI for active infection may be particularly limited with certain conditions, including neuropathic (Charcot) osteoarthropathy, prior surgery, and some neoplasms.

MRI findings with high specificity for osteomyelitis include the presence of a cortical perforation (cloaca) connecting abscesses in bone and adjacent to bone.

IV contrast material can help to delineate cloacae and sinus tracts, differentiate abscesses from phlegmon, and show areas of devitalized (necrotic) tissue.

Suggested Readings

- 286 Boutin RD, Brossmann J, Sartoris DJ, Reilly D, Resnick D. Update on imaging of orthopedic infections.. Orthop Clin North Am 1998; 29 (1) 41-66 PubMed 9405777

- 287 Desimpel J, Posadzy M, Vanhoenacker F. The many faces of osteomyelitis: a pictorial review.. J Belg Soc Radiol 2017; 101 (1) 24 PubMed 30039016

- 288 Jaramillo D, Dormans JP, Delgado J, Laor T, St Geme III JW. Hematogenous osteomyelitis in infants and children: imaging of a changing disease.. Radiology 2017; 283 (3) 629-643 PubMed 28514223

- 289 Kompel A, Murakami A, Guermazi A. Magnetic resonance imaging of nontraumatic musculoskeletal emergencies.. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am 2016; 24 (2) 369-389 PubMed 27150324

- 290 Lee YJ, Sadigh S, Mankad K, Kapse N, Rajeswaran G. The imaging of osteomyelitis.. Quant Imaging Med Surg 2016; 6 (2) 184-198 PubMed 27190771

- 291 Sconfienza LM, Signore A, Cassar-Pullicino V et al. Diagnosis of peripheral bone and prosthetic joint infections: overview on the consensus documents by the EANM, EBJIS, and ESR (with ESCMID endorsement). Eur Radiol 2019; 29 (12) 6425-6438 PubMed 31250170

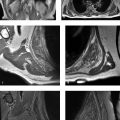

Case 88

Clinical History

A 49-year-old man with a history of chemotherapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia and a posterior elbow mass (Fig. 88‑1).

Key Finding

Space-occupying lesion posterior to the olecranon.

Top 3 Differential Diagnoses

Olecranon bursitis, noninfectious (nonseptic): Bursae are sac-like structures that normally have a thin synovial lining, but can become inflamed and distended with many different types of acute and chronic derangements (e.g., blunt trauma, repetitive microtrauma, inflammatory arthritis such as rheumatoid arthritis, and crystal-induced arthropathy such as gout).

Clinically, swelling and inflammation at the dorsal aspect of the elbow are nonspecific findings. Bursal fluid aspiration may be useful for laboratory analysis (e.g., assess for monosodium urate crystals and rule out infection). More than two-thirds of olecranon bursitis cases are noninfectious. However, of patients with infectious bursitis, about one-third have a history of a previous episode of noninfectious olecranon bursitis.

Olecranon bursitis, infectious (septic): Two superficial bursae are located in the subcutaneous fat layer and are prone to infection in the setting of penetrating trauma: the olecranon bursa and the prepatellar bursa. Direct inoculation of pathogens into these bursae classically occurs with a puncture wound or abrasion. Septic olecranon bursitis is much more common than septic arthritis in adults. Impaired immunity is an important risk factor in up to half of all cases of septic elbow olecranon bursitis (e.g., alcohol abuse, diabetes, malignancy such as chronic lymphocytic leukemia, and medications such as chemotherapy, corticosteroids and anti-TNF drugs).

Imaging may be used to assess the underlying bone and joint (e.g., rule out osteomyelitis and joint effusion). There is considerable overlap in the imaging findings of infectious and noninfectious olecranon bursitis (e.g., volume of bursal fluid, bursal septation, or olecranon bone marrow signal changes). However, septic olecranon bursitis can be excluded in the absence of bursal and soft-tissue enhancement.

Neoplasm: Neoplasms may occur superficial to the fascia in the subcutaneous layer, and they may be evaluated by diagnostic imaging. When MRI is performed, IV contrast material can be very helpful to differentiate cystic versus solid lesions.

Proper imaging before sarcoma surgery is of paramount importance, because initial optimal wide resection is one of the most important factors for avoiding local recurrence (usually ranging from 11–23%). Because sarcomas start out as small tumors and may be superficial, radiologists can help surgeons avoid problematic “unplanned excisions” (also referred to as “whoops surgeries”) by maintaining a high level of suspicion if an indeterminant solid lesion is present.

Diagnosis

Olecranon bursitis, infectious.

Pearls

If a patient has a history of skin disruption over the olecranon or impaired immunity, a higher index of suspicion for an infectious form of olecranon bursitis is appropriate.

The cause of bursitis may not necessarily be determined based on clinical findings or imaging findings in isolation. Aspiration of bursal contents for laboratory analysis may be appropriate.

Although superficial soft-tissue masses are often benign, it is important to recall that subcutaneous soft-tissue sarcomas are sometimes small and mismanaged.

Suggested Readings

- 292 Blackwell JR, Hay BA, Bolt AM, Hay SM. Olecranon bursitis: a systematic overview.. Shoulder Elbow 2014; 6 (3) 182-190 PubMed 27582935

- 293 Boutin FJ, Boutin RD, Boutin FJ Jr. Bursitis. In: Chapman MW, Madison M, eds. Operative Orthopaedics. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott;1993:3419–3432

- 294 Dyrop HB, Safwat A, Vedsted P et al. Characteristics of 64 sarcoma patients referred to a sarcoma center after unplanned excision.. J Surg Oncol 2016; 113 (2) 235-239 PubMed 26776152

- 295 Endo M, Setsu N, Fujiwara T et al. Diagnosis and management of subcutaneous soft tissue sarcoma.. Curr Treat Options Oncol 2019; 20 (7) 54 PubMed 31129726

- 296 Floemer F, Morrison WB, Bongartz G, Ledermann HP. MRI characteristics of olecranon bursitis.. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2004; 183 (1) 29-34 PubMed 15208103

- 297 Morel M, Taïeb S, Penel N et al. Imaging of the most frequent superficial soft-tissue sarcomas.. Skeletal Radiol 2011; 40 (3) 271-284 PubMed 20069421

- 298 Reilly D, Kamineni S. Olecranon bursitis.. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2016; 25 (1) 158-167 PubMed 26577126

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree