Infection of the central nervous system (CNS) in children is an important entity and early recognition is paramount to avoid long-term brain injury, especially in very young patients. The causal factors are different in children compared with adults and so are the clinical presentations. However, imaging features of CNS infection show similar features to those of adults. This article reviews some of the common types of pediatric infections, starting with the congenital (or in utero) infections followed by bacterial infections of the meninges and brain parenchyma.

- •

As in adults, imaging is crucial to look for complications of intracranial infection.

- •

In very young children, the clinical features of intracranial infection are nonspecific and imaging may help in suggesting a diagnosis.

- •

Cytomegalovirus is the commonest type of congenital infection.

- •

Infectious bacterial meningitis is the commonest type of intracranial infection in children.

- •

In patients with recurrent episodes of meningitis, it is important to look for a possible osteodural break, like spinal dermal sinus or nasal dermal sinus.

Introduction

Infection of the central nervous system (CNS) in children is an important entity and early recognition is paramount to avoid long-term brain injury, especially in very young patients. The causal factors are different in children compared with adults and so are the clinical presentations. However, imaging features of CNS infection show similar features to those of adults. This article reviews some of the common types of pediatric infections, starting with the congenital (or in utero) infections followed by bacterial infections of the meninges and brain parenchyma. The viral infections are also reviewed. CNS tuberculosis and fungal and parasitic infections are discussed separately in this issue and are not discussed in this article.

Congenital infections

Congenital infections are transmitted to the fetus from the mother through the transplacental route or during birth. The mnemonic TORCH is often used to describe these entities, which stands for toxoplasmosis, others (syphilis, human immunodeficiency virus [HIV]), rubella, cytomegalovirus (CMV), and herpes simplex virus (HSV) type 2. All these are transmitted to the fetus from primary maternal infections, except for herpes, which is acquired during parturition. It is important to realize that infections of the fetus have long-term effects and sequelae on the developing brain. These sequelae depend on the fetal age at the time of infections, the cellular susceptibility to the infecting agent and host immune responses. Insults in the first or second trimesters typically result in CNS malformations (like microcephaly, lissencephaly, or polymicrogyria), whereas infections in the third trimester result in destructive lesions like aqueductal stenosis and hydrocephalus, porencephaly, multicystic encephalomalacia, calcifications, demyelination, and atrophy.

Toxoplasmosis

Toxoplasmosis is caused by Toxoplasma gondii , an intracellular parasite that infects birds and mammals. Cats usually serve as primary hosts for the parasites. Domestic animals like pigs and cattle serve as intermediate hosts. Human infection occurs through consumption of undercooked, infected meat or by ingestion of infectious oocysts. When primary infection happens during pregnancy, the parasites are disseminated hematogenously to the placenta and the fetus. Although the transmission rate from the mother to the fetus increases with each trimester, the severity of infection decreases with each trimester. It has been estimated that the rate of transmission of Toxoplasma in first trimester is 17%, in the second trimester it is 25%, and 65% in the third trimester. Early first-trimester infection by Toxoplasma causes spontaneous abortions, infections in the second trimester lead to fetal death or severe disease, whereas infection in the last trimester are often mild and subclinical. Approximately 10% of infected patients presents with clinical symptoms. Symptoms are either present at the time of birth or present several days afterward. Patients exhibit hepatosplenomegaly, jaundice, and rash. They have chorioretinitis (bilateral in 85%), hydrocephalus, microcephaly, and intracranial calcifications. In children affected with CNS toxoplasmosis, the prognosis is poor with overall mortality ranging from 11% to 14%. Those who survive have long-term sequelae like seizures, spasticity, and developmental delay. Within the cranium there is diffuse inflammation of the meninges, with varying sized granulomatous lesions. Inflammation of the ependyma (ependymitis) causes obstruction of the cerebral aqueduct leading to hydrocephalus. Unlike CMV infection, there is no malformation of cortical development seen with toxoplasmosis. On imaging, calcifications are common. These calcifications are seen in the basal nuclei, periventricular regions, or cerebral parenchyma ( Fig. 1 ). If hydrocephalus is present, it is characterized by marked dilatation of the lateral and third ventricles. In infants with severe infection, there is marked destruction with hydrocephalus, porencephaly, and extensive basal ganglia calcifications. In cases with mild infection (typically after the 30th week of gestation) there is mild ventricular enlargement and few intracranial calcifications.

HIV

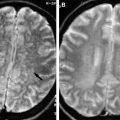

Since the first description of neonatal acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) in 1982, HIV infection and AIDS has become a significant public health problem because of the large number of HIV-positive women of childbearing age. Approximately 78% of childhood HIV infection is maternally transmitted and about 40% of HIV-positive mothers pass on their infection to the fetus. This has been shown to reduce dramatically with antiretroviral treatment of mothers and delivery by cesarean section. Mother-to-child transmission can occur in utero, intrapartum during birth, or postpartum during breast-feeding. Children with congenital HIV infection are often asymptomatic at birth and manifest neurologic signs or symptoms between 2 months and 5 years of age. They usually show progressive developmental delay, microcephaly, generalized lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, recurrent diarrhea, or oral candidiasis. Two major neurological syndromes have been described. In progressive encephalopathy, patients become demented, spastic, and show decreased rates of head growth. In static encephalopathy, there is a delay in cognitive and motor development. In contrast with adults, children rarely develop opportunistic CNS complications like lymphoma or toxoplasmosis. On pathology, HIV encephalitis is associated with glial and microglial nodules in the basal ganglia, brain stem, and white matter with multinuclear giant cells. Perivascular calcifications are seen most prominently in the basal ganglia. Perivascular inflammation with demyelination is also seen. On imaging, there is cerebral atrophy with ventricular and sulcal prominence. Intracranial calcifications are seen caused by vasculitis in which calcium is deposited around small affected blood vessels. Children with higher viral loads show more calcifications. White matter abnormality is seen as decrease in attenuation of computed tomography (CT) and increased T2 signal on magnetic resonance (MR) imaging ( Fig. 2 A, B). Corticospinal tract degeneration and demyelination is sometimes seen. Parenchymal hemorrhage and infarction are rare complications of congenital HIV infection.

Syphilis

Congenital syphilis is caused by a spirochete, Treponema pallidum . Humans are the only natural host of the spirochete and transmit the organism with intimate contact or contact with bodily fluids. The fetus is infected via the transplacental route, the risk being greatest during the stage of secondary syphilis because of the high load of spirochetes circulating in the mother. Infection after 24 weeks of gestation is also at increased risk. Signs of congenital syphilis in an affected child include long bone periostitis, hepatosplenomegaly, jaundice, skin rash, lymphadenopathy, meningitis, and hydrocephalus. Without treatment, late stigmata of the disease can be seen, which includes facial and skin deformities, sensorineural hearing loss, mental retardation, seizures, and hemiplegia. Intracranial involvement results in meningovascular and parenchymal syphilis. Om imaging, there is enhancement of the leptomeninges. The enhancement may extend along the perivascular space into the brain parenchyma and appears as an enhancing parenchymal mass. Inflammatory vasculitis can result in arterial infarctions.

Rubella

Congenital rubella is extremely rare nowadays because of the immunization program and maternal screening during pregnancy. The risk of fetal infection is greater during the first and second trimesters. Affected infants presents with congenital rubella syndrome, which includes growth retardation, ocular abnormalities (cataracts and pigmentory retinopathy), congenital heart defects (patent ductus arteriosus and pulmonary artery stenosis), hepatosplenomegaly, jaundice, and purpuric rash. Neurologic manifestations include hearing loss, microcephaly, meningoencephalitis, psychomotor retardation, speech defects, hypotonia, autism, and bulging fontanelle. Some of these features are present at birth, some develop later. On pathology, affected brain shows microcephaly with ventricular prominence. There are multiple small areas of necrosis and gliosis with calcification in the periventricular white matter, basal ganglia, and brainstem, often as a result of vasculopathy. Myelination is impaired as well. On imaging, there is intracranial calcification in the basal ganglia, periventricular region, and cortex. Multifocal areas of T2/fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) hyperintensity and delayed brain myelination patterns are also seen ( Fig. 3 A, B). CT of the temporal bones may show inner ear malformations.

CMV

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is the commonest viral infection of newborns, with more than 50% of women of childbearing age considered to be seropositive. Neonatal infection happens when maternal infection or reactivation of infection happens during pregnancy. CMV occurs in approximately 1% of all births, and approximately 10% of these children have hematological, neurologic, and developmental features. Hepatosplenomegaly and skin petechiae are the most commonly seen features. CNS abnormalities are seen in roughly 55% of patients, which includes intracranial calcifications, microcephaly, hearing abnormalities, chorioretinitis, and seizures in order of decreasing frequency. Transmission from mother to fetus occurs through the placenta, through direct contact with maternal secretions at the time of birth, or during breast-feeding. Those infected early in gestation have severe disease in which there is multifocal destruction of tissue with associated hemorrhage and dystrophic calcifications. The periventricular subependymal germinal matrix cells are considered most susceptible to early infection. As a result, apart from periventricular calcifications, there are changes of cortical migrational disorders like lissencephaly, polymicrogyria, heterotopias, and microcephaly. Infection in later gestation produces hydranencephaly and porencephaly. Infection in the third trimester is a clinical syndrome characterized by microcephaly, hearing loss, hyperactivity, ataxia, hypotonia, and behavior problems. The imaging features depend on the fetal age at the time of infection and the degree of infection. Patients infected in the first trimester have lissencephaly with thin cortex, cerebellar hypoplasia, delayed myelination, marked ventriculomegaly, and significant periventricular calcifications ( Fig. 4 A, B). Patients with injury later in the second trimester have polymicrogyria and less ventricular dilatation with scattered periventricular calcification or hemorrhage ( Fig. 5 ). Infections late in the third trimester or early postnatal period result in mild ventricular prominence. These patients show abnormal white matter signal in the periventricular and subcortical regions, and involvement of the anterior temporal white matter (often with cyst formation ; Fig. 6 A, B), and show scattered periventricular calcifications.

HSV 2

Unlike HSV 1 (discussed later), HSV 2 infection is sexually transmitted and associated with genital lesions. Congenital HSV infection is not a congenital infection; the child acquires the infection during birth because of contact with genital lesions of the affected mother. Thirty percent of affected infants have brain involvement and, of these, almost 80% do not survive the infection. Primary CNS infection by HSV in neonates is diffuse and nonfocal, resulting in widespread involvement and brain destruction. In surviving children, severe neurologic sequelae like seizures, microcephaly, multicystic encephalomalacia, and ventriculomegaly are seen. On neuroimaging, findings are nonspecific, especially in the earlier part of the disease. Unlike HSV infection in adults, which tends to localize more in the frontal and temporal lobes, the HSV 2 infection in neonates is diffuse and multifocal, often mimicking changes of diffuse hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. These changes are seen as hypoattenuation on CT ( Fig. 7 A, B) and hyperintensity on the T2-weighted images (see Fig. 7 C). Diffusion-weighted images reveal brain involvement earlier than routine sequences and should be obtained (see Fig. 7 D). Contrast enhancement is minimal and suggests meningeal involvement. There is eventually severe brain atrophy, encephalomalacia, dystrophic calcification, and ventriculomegaly. Cerebellar involvement is seen in roughly half the patients.

Congenital infections

Congenital infections are transmitted to the fetus from the mother through the transplacental route or during birth. The mnemonic TORCH is often used to describe these entities, which stands for toxoplasmosis, others (syphilis, human immunodeficiency virus [HIV]), rubella, cytomegalovirus (CMV), and herpes simplex virus (HSV) type 2. All these are transmitted to the fetus from primary maternal infections, except for herpes, which is acquired during parturition. It is important to realize that infections of the fetus have long-term effects and sequelae on the developing brain. These sequelae depend on the fetal age at the time of infections, the cellular susceptibility to the infecting agent and host immune responses. Insults in the first or second trimesters typically result in CNS malformations (like microcephaly, lissencephaly, or polymicrogyria), whereas infections in the third trimester result in destructive lesions like aqueductal stenosis and hydrocephalus, porencephaly, multicystic encephalomalacia, calcifications, demyelination, and atrophy.

Toxoplasmosis

Toxoplasmosis is caused by Toxoplasma gondii , an intracellular parasite that infects birds and mammals. Cats usually serve as primary hosts for the parasites. Domestic animals like pigs and cattle serve as intermediate hosts. Human infection occurs through consumption of undercooked, infected meat or by ingestion of infectious oocysts. When primary infection happens during pregnancy, the parasites are disseminated hematogenously to the placenta and the fetus. Although the transmission rate from the mother to the fetus increases with each trimester, the severity of infection decreases with each trimester. It has been estimated that the rate of transmission of Toxoplasma in first trimester is 17%, in the second trimester it is 25%, and 65% in the third trimester. Early first-trimester infection by Toxoplasma causes spontaneous abortions, infections in the second trimester lead to fetal death or severe disease, whereas infection in the last trimester are often mild and subclinical. Approximately 10% of infected patients presents with clinical symptoms. Symptoms are either present at the time of birth or present several days afterward. Patients exhibit hepatosplenomegaly, jaundice, and rash. They have chorioretinitis (bilateral in 85%), hydrocephalus, microcephaly, and intracranial calcifications. In children affected with CNS toxoplasmosis, the prognosis is poor with overall mortality ranging from 11% to 14%. Those who survive have long-term sequelae like seizures, spasticity, and developmental delay. Within the cranium there is diffuse inflammation of the meninges, with varying sized granulomatous lesions. Inflammation of the ependyma (ependymitis) causes obstruction of the cerebral aqueduct leading to hydrocephalus. Unlike CMV infection, there is no malformation of cortical development seen with toxoplasmosis. On imaging, calcifications are common. These calcifications are seen in the basal nuclei, periventricular regions, or cerebral parenchyma ( Fig. 1 ). If hydrocephalus is present, it is characterized by marked dilatation of the lateral and third ventricles. In infants with severe infection, there is marked destruction with hydrocephalus, porencephaly, and extensive basal ganglia calcifications. In cases with mild infection (typically after the 30th week of gestation) there is mild ventricular enlargement and few intracranial calcifications.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree