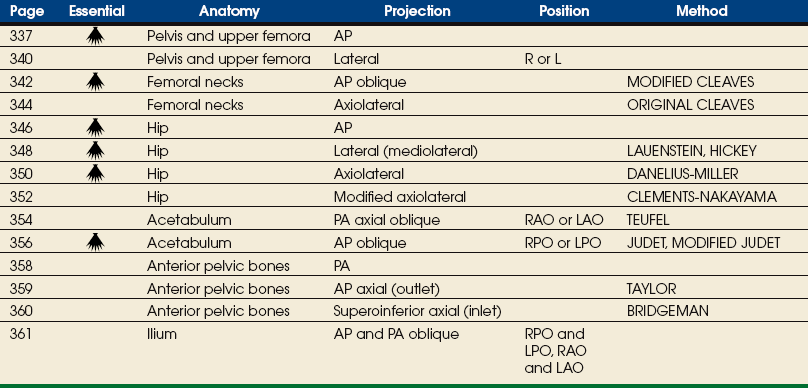

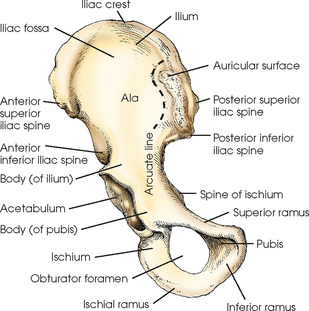

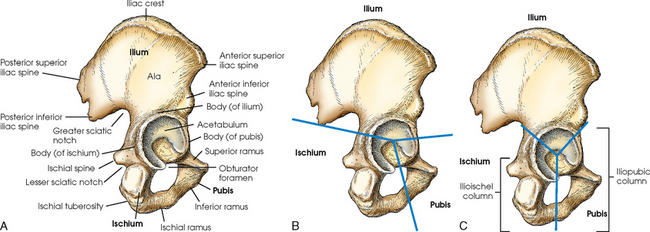

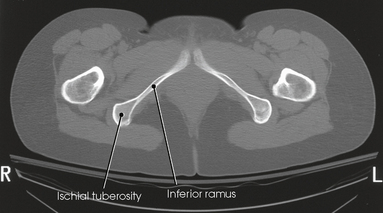

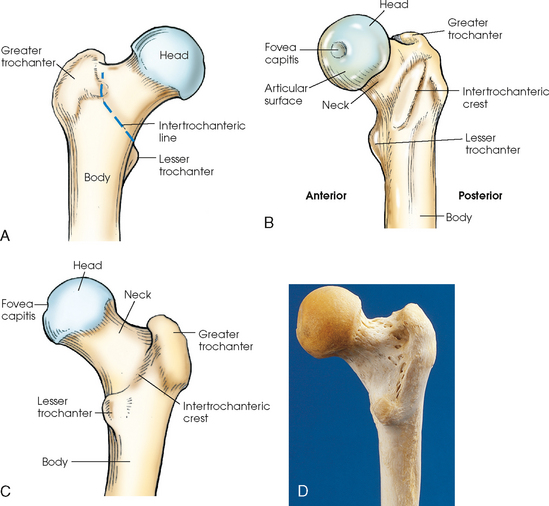

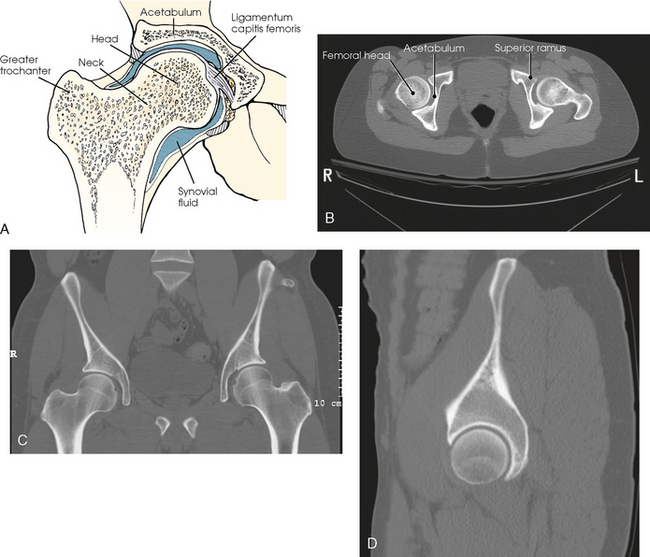

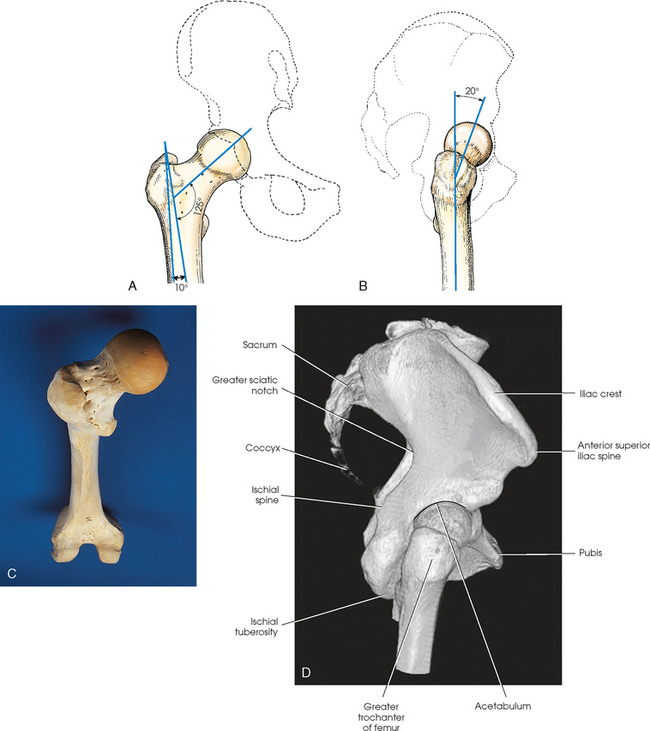

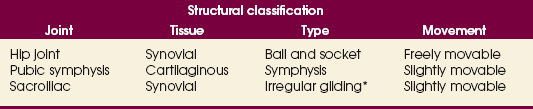

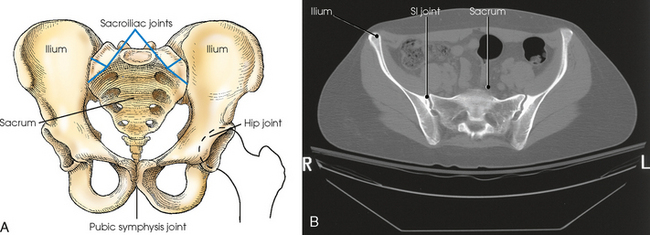

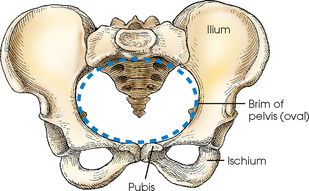

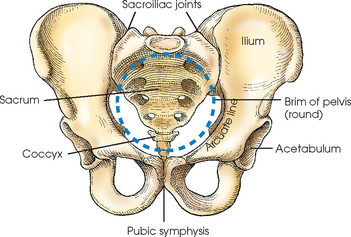

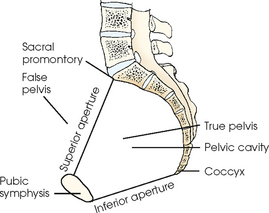

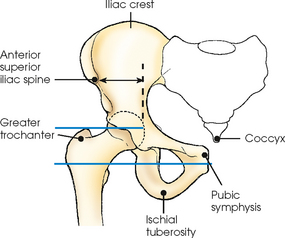

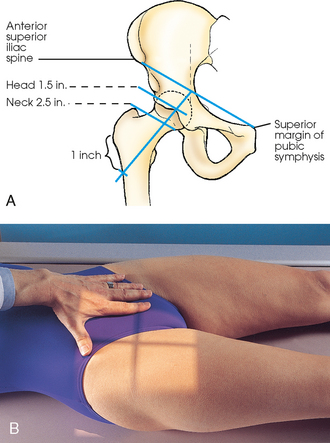

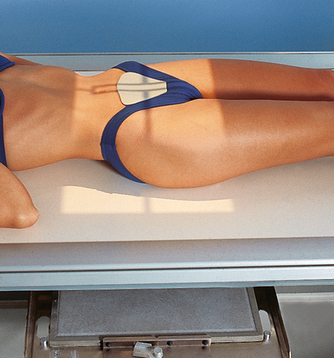

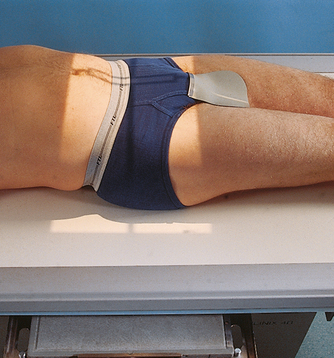

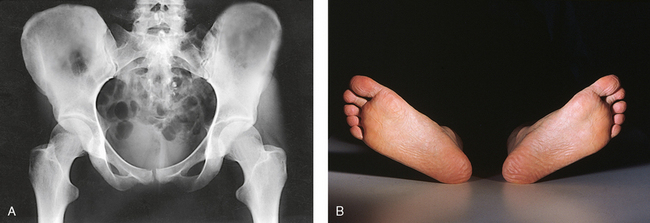

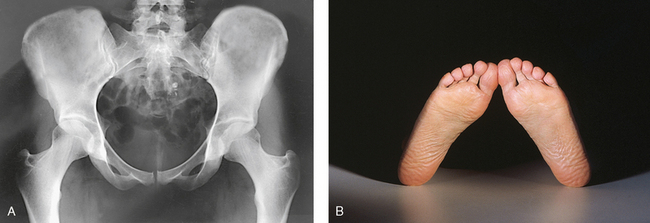

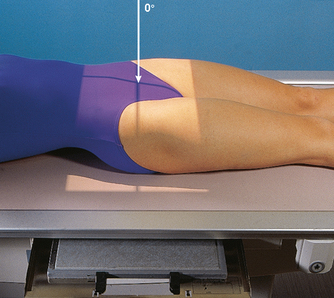

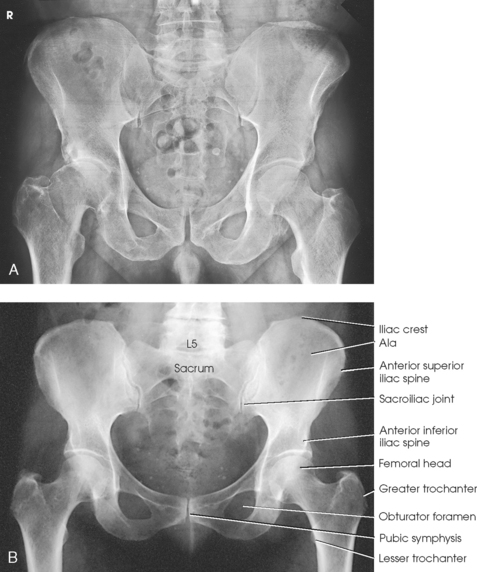

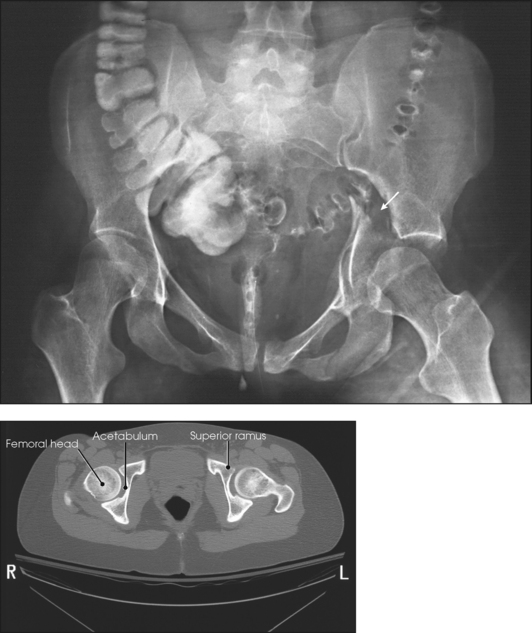

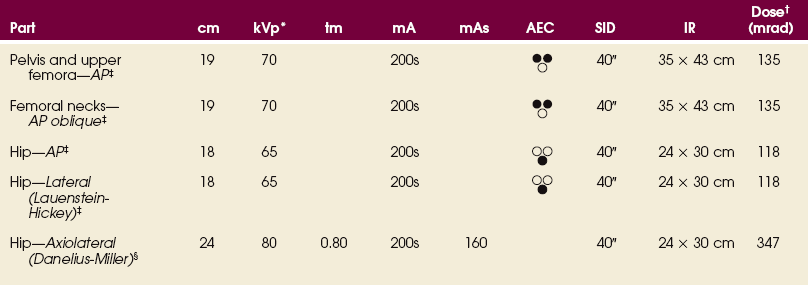

7 The hip bone consists of the ilium, pubis, and ischium (Figs. 7-1 and 7-2). These three bones join together to form the acetabulum, the cup-shaped socket that receives the head of the femur. The ilium, pubis, and ischium are separated by cartilage in children but become fused into one bone in adults. The hip bone is divided further into two distinct areas: the iliopubic column and the ilioischial column (see Fig. 7-2, C). These columns are used to identify fractures around the acetabulum. The ilium consists of a body and a broad, curved portion called the ala. The body of the ilium forms approximately two fifths of the acetabulum superiorly (Fig. 7-3). The ala projects superiorly from the body to form the prominence of the hip. The ala has three borders: anterior, posterior, and superior. The anterior and posterior borders present four prominent projections: The pubis consists of a body, the superior ramus, and the inferior ramus. The body of the pubis forms approximately one fifth of the acetabulum anteriorly (see Fig. 7-2). The superior ramus projects inferiorly and medially from the acetabulum to the midline of the body. There the bone curves inferiorly and then posteriorly and laterally to join the ischium. The lower prong is termed the inferior ramus. The ischium consists of a body and the ischial ramus. The body of the ischium forms approximately two fifths of the acetabulum posteriorly (see Figs. 7-2 and 7-3). It projects posteriorly and inferiorly from the acetabulum to form an expanded portion called the ischial tuberosity. When the body is in a seated-upright position, its weight rests on the two ischial tuberosities. The ischial ramus projects anteriorly and medially from the tuberosity to its junction with the inferior ramus of the pubis. By this posterior union the rami of the pubis and ischium enclose the obturator foramen. At the superoposterior border of the body is a prominent projection called the ischial spine. An indentation, the lesser sciatic notch, is just below the ischial spine. The femur is the longest, strongest, and heaviest bone in the body. The proximal end of the femur consists of a head, a neck, and two large processes: the greater and lesser trochanters (Fig. 7-4). The smooth, rounded head is connected to the femoral body by a pyramid-shaped neck and is received into the acetabular cavity of the hip bone. A small depression at the center of the head, the fovea capitis, attaches to the ligamentum capitis femoris (Fig. 7-5; see Fig. 7-4). The neck is constricted near the head but expands to a broad base at the body of the bone. The neck projects medially, superiorly, and anteriorly from the body. The trochanters are situated at the junction of the body and the base of the neck. The greater trochanter is at the superolateral part of the femoral body, and the lesser trochanter is at the posteromedial part. The prominent ridge extending between the trochanters at the base of the neck on the posterior surface of the body is called the intertrochanteric crest. The less prominent ridge connecting the trochanters anteriorly is called the intertrochanteric line. The femoral neck and the intertrochanteric crest are two common sites of fractures in elderly adults. The superior portion of the greater trochanter projects above the neck and curves slightly posteriorly and medially. The angulation of the neck of the femur varies considerably with age, sex, and stature. In the average adult, the neck projects anteriorly from the body at an angle of approximately 15 to 20 degrees and superiorly at an angle of approximately 120 to 130 degrees to the long axis of the femoral body (Fig. 7-6). The longitudinal plane of the femur is angled about 10 degrees from vertical. In children, the latter angle is wider—that is, the neck is more vertical in position. In wide pelves, the angle is narrower, placing the neck in a more horizontal position. Table 7-1 and Fig. 7-7 provide a summary of the three joints of the pelvis and upper femora. The articulation between the acetabulum and the head of the femur (the hip joint) is a synovial ball-and-socket joint that permits free movement in all directions. The knee and ankle joints are hinge joints; the wide range of motion of the lower limb depends on the ball-and-socket joint of the hip. Because the knee and ankle joints are hinge joints, medial and lateral rotations of the foot cause rotation of the entire limb, which is centered at the hip joint. The right and left ilia articulate with the sacrum posteriorly at the sacroiliac (SI) joints. These two joints angle 25 to 30 degrees relative to the midsagittal plane (see Fig. 7-7, B). The SI articulations are synovial irregular gliding joints. Because the bones of the SI joints interlock, movement is limited or nonexistent. The female pelvis (Fig. 7-8) is lighter in structure than the male pelvis (Fig. 7-9). It is wider and shallower, and the inlet is larger and more oval-shaped. The sacrum is wider, it curves more sharply posteriorly, and the sacral promontory is flatter. The width and depth of the pelvis vary with stature and gender (Table 7-2). The female pelvis is shaped for childbearing and delivery. TABLE 7-2 Female and male pelvis characteristics The pelvis is divided into two portions by an oblique plane that extends from the upper anterior margin of the sacrum to the upper margin of the pubic symphysis. The boundary line of this plane is called the brim of the pelvis (see Figs. 7-8 and 7-9). The region above the brim is called the false or greater pelvis, and the region below the brim is called the true or lesser pelvis. The brim forms the superior aperture, or inlet, of the true pelvis. The inferior aperture, or outlet, of the true pelvis is measured from the tip of the coccyx to the inferior margin of the pubic symphysis in the anteroposterior direction and between the ischial tuberosities in the horizontal direction. The region between the inlet and the outlet is called the pelvic cavity (Fig. 7-10). The bony landmarks used in radiography of the pelvis and hips are as follows: Most of these points are easily palpable, even in hypersthenic patients (Fig. 7-11). Because of the heavy muscles immediately above the iliac crest, care must be exercised in locating this structure to avoid centering errors. Having the patient inhale deeply is advisable; while the muscles are relaxed during expiration, the radiographer should palpate for the highest point of the iliac crest. The highest point of the greater trochanter, which can be palpated immediately below the depression in the soft tissues of the lateral surface of the hip, is in the same horizontal plane as the midpoint of the hip joint and the coccyx. The most prominent point of the greater trochanter is in the same horizontal plane as the pubic symphysis (see Fig. 7-11). The hip joint can be located by palpating the ASIS and the superior margin of the pubic symphysis (Fig. 7-12). The midpoint of a line drawn between these two points is directly above the center of the dome of the acetabular cavity. A line drawn at right angles to the midpoint of the first line lies parallel to the long axis of the femoral neck of an average adult in the anatomic position. The femoral head lies 1½ inches (3.8 cm) distal, and the femoral neck is 2½ (6.4 cm) distal to this point. For accurate localization of the femoral neck in atypical patients or in patients in whom the limb is not in the anatomic position, a line is drawn between the ASIS and the superior margin of the pubic symphysis, and a second line is drawn from a point 1 inch (2.5 cm) inferior to the greater trochanter to the midpoint of the previously marked line. The femoral head and neck lies along this line (see Fig. 7-12). *kVp values are for a three-phase, 12-pulse generator or high frequency. †Relative doses for comparison use. All doses are skin entrance for average adult at cm indicated. ‡Bucky, 16:1 grid. Screen-film speed 300 or equivalent CR. Protection of the patient from unnecessary radiation is a professional responsibility of the radiographer (see Chapter 1 for specific guidelines). In this chapter, the Shield gonads statement at the end of the Position of part section indicates that the patient is to be protected from unnecessary radiation by restricting the radiation beam using proper collimation. In addition, placing lead shielding between the gonads and the radiation source is appropriate when the clinical objectives of the examination are not compromised (Figs. 7-13 and 7-14). • Center the midsagittal plane of the body to the midline of the grid, and adjust it in a true supine position. • Unless contraindicated because of trauma or pathologic factors, medially rotate the feet and lower limbs about 15 to 20 degrees to place the femoral necks parallel with the plane of the image receptor (IR) (Figs. 7-15 and 7-16). Medial rotation is easier for the patient to maintain if the knees are supported. The heels should be placed about 8 to 10 inches (20 to 24 cm) apart. • Immobilize the legs with a sandbag across the ankles, if necessary. • Check the distance from ASIS to the tabletop on each side to be sure that the pelvis is not rotated. • Center the IR midway between ASIS and pubic symphysis. In average-sized patients, the center of the IR is about 2 inches (5 cm) inferior to ASIS and 2 inches (5 cm) superior to pubic symphysis (Fig. 7-17). • If the pelvis is deep, palpate for the iliac crest and adjust the position of the IR so that its upper border projects 1 to 1½ inches (2.5 to 3.8 cm) above the crest.

PELVIS AND UPPER FEMORA

Hip Bone

ILIUM

PUBIS

ISCHIUM

Proximal Femur

Articulations of the Pelvis

Pelvis

Feature

Female

Male

Shape

Wide, shallow

Narrow, deep

Bony structure

Light

Heavy

Superior aperture (inlet)

Oval

Round

Inferior aperture (outlet)

Wide

Narrow

Localizing Anatomic Structures

SUMMARY OF PATHOLOGY

Condition

Definition

Ankylosing spondylitis

Rheumatoid arthritis variant involving the SI joints and spine

Congenital hip dysplasia

Malformation of the acetabulum causing displacement of the femoral head

Dislocation

Displacement of a bone from the joint space

Fracture

Disruption in the continuity of bone

Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease

Flattening of the femoral head owing to vascular interruption

Metastases

Transfer of a cancerous lesion from one area to another

Osteoarthritis or degenerative joint disease

Form of arthritis marked by progressive cartilage deterioration in synovial joints and vertebrae

Osteopetrosis

Increased density of atypically soft bone

Osteoporosis

Loss of bone density

Paget disease

Thick, soft bone marked by bowing and fractures

Slipped epiphysis

Proximal portion of femur dislocated from distal portion at the proximal epiphysis

Tumor

New tissue growth where cell proliferation is uncontrolled

Chondrosarcoma

Malignant tumor arising from cartilage cells

Multiple myeloma

Malignant neoplasm of plasma cells involving the bone marrow and causing destruction of the bone

EXPOSURE TECHNIQUE CHART ESSENTIAL PROJECTIONS

RADIOGRAPHY

Pelvis and Upper Femora