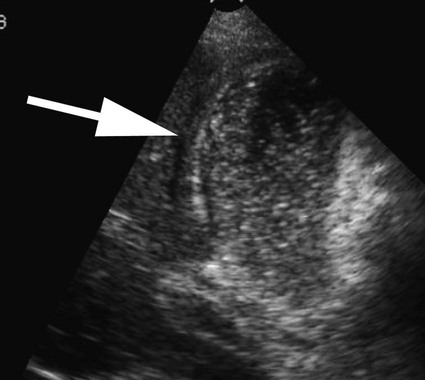

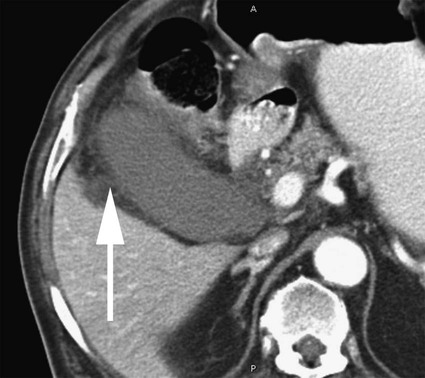

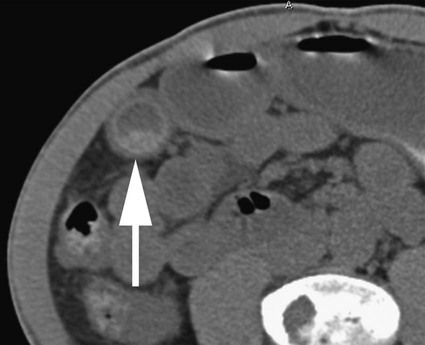

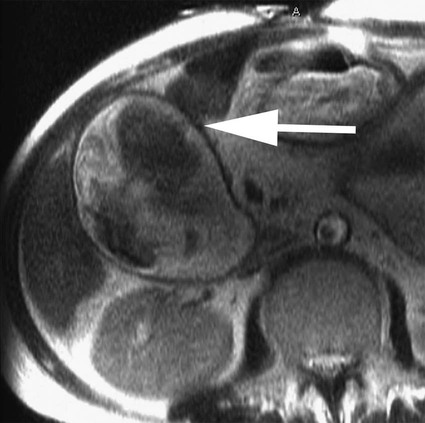

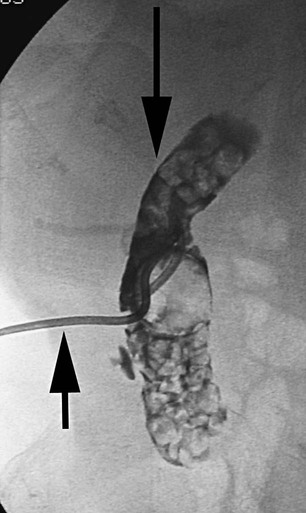

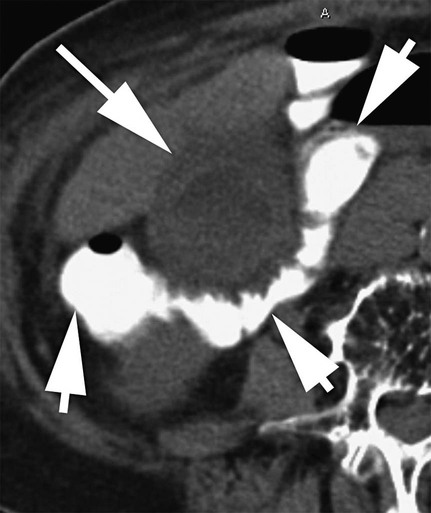

Thomas M. Fahrbach, Gerald M. Wyse, Leo P. Lawler and Hyun S. Kim Acute cholecystitis (AC) is a prevalent condition that carries significant risks of morbidity and mortality.1 AC may present with a spectrum of disease stages ranging from a mild self-limited illness to a fulminant potentially life-threatening illness.2 Laparoscopic or open surgical removal of the inflamed gallbladder remains the gold-standard therapy when the patient is a surgical candidate.3,4 However, because surgery requires general anesthesia, incisions, and postoperative recuperation, percutaneous cholecystostomy (PC) has served to largely replace surgery in patients who have significant comorbidities or anatomic variations that may preclude or delay surgical therapy.5–8 This minimally invasive nonsurgical approach has in fact been suggested as definitive therapy in critically ill and elderly patients,9 as well as to provide a bridge to surgery.10,11 The overall goal of PC is gallbladder decompression and drainage for prevention of gallbladder perforation and sepsis.12–16 The technique of PC also offers a minimally invasive means of access to the biliary system for other interventions such as stent placement and stone retrieval.17–20 As just noted, there are primarily two clinical reasons patients are referred for cholecystostomy: (1) to decompress the gallbladder for management of cholecystitis21 or (2) to provide a portal of access to the biliary tract for therapeutic purposes.22 A multidisciplinary approach to determine whether to proceed with PC is ideal and should be guided by clinical symptomatology, laboratory data, and supporting imaging evidence.22 The clinical manifestations of cholecystitis include fever, elevated white blood cell count, right upper quadrant pain, and Murphy sign. Patients may suffer from either calculous or acalculous cholecystitis (Figs. 137-1 to 137-4).23,24 Those with calculous cholecystitis have gallstones and possibly sludge causing mechanical obstruction of the cystic duct. The exact pathogenesis of acalculous cholecystitis is unclear but tends to occur in the critically ill, debilitated, or intensive care patients. Associations with diabetes, malignant disease, vasculitis, and congestive heart failure also exist,25 as well as being secondary to mechanical obstruction of the cystic duct from biliary stent placement in the common bile duct. Empirical cholecystostomy may be indicated in patients with fever of unknown origin or other clinical evidence of sepsis where there is no apparent source other than classic imaging features of cholecystitis. Sonographic, computed tomography (CT), or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings of uncomplicated cholecystitis include gallbladder wall thickening, pericholecystic fluid/stranding, gallbladder distension, sonographic Murphy sign (right upper quadrant pain with probe pressure), or a gallstone impacted in the neck of the gallbladder or cystic duct.26,27 Findings of complicated cholecystitis such as pericholecystic abscess, intraluminal membranes, and/or gas suggest a gangrenous or perforated gallbladder.28 Hepatobiliary nuclear scintigraphy with technetium (Tc)-99m iminodiacetic acid derivatives provides highly specific diagnostic confirmation, with nonvisualization of the gallbladder at 4 hours suggesting cystic duct obstruction and cholecystitis.29 Frequently, PC is performed in gravely ill and high-risk patients, and there are few absolute contraindications. Interposed bowel (e.g., as in Chilaiditi syndrome) may preclude safe access to the gallbladder. Coagulopathy is a relative contraindication, and a severe bleeding diathesis may not allow transhepatic access. Other relative contraindications include gallbladder tumor that may be seeded by percutaneous access, or a gallbladder greatly distended by calculi that prevent drainage tube formation and locking (Fig. 137-5). Finally, it may be difficult or impossible to place a PC tube in a perforated decompressed gallbladder. Percutaneous access to the gallbladder can be achieved via direct image guidance with ultrasound, fluoroscopy, or CT. The preferred method of ultrasound guidance is normally performed with a midrange frequency 2- to 8-Hz curvilinear array sector probe. The procedure may be performed at the bedside when necessary,16,30 but catheter insertion is best performed in a fluoroscopy suite. Axial noncontrast CT may be used, and CT fluoroscopy tools are rarely necessary but may be helpful when a significantly diseased or calcular gallbladder limits sonographic visualization of the lumen.31 Standard sterile technique should always be used. The gallbladder may be approached via one of two basic methods: transhepatic or transperitoneal. In general, the transhepatic route involves an arc from the right midaxillary line to the midclavicular line (Fig. 137-6), and hypothetically traverses the bare area of the gallbladder (superior third portion of the gallbladder).31 A track is chosen below the diaphragm, which may or may not be intercostal. Intercostal access is immediately above the rib to avoid the neurovascular bundle (Fig. 137-7). It is important to exclude any ascending colon or hepatic flexure interposed between the liver and abdominal wall along the anticipated track. The transhepatic approach generally traverses segments 5 or 6 and enters the gallbladder through the gallbladder fossa (see Fig. 137-7). The transperitoneal approach is generally anterior or anterolateral, and similarly, interposed bowel must be excluded (Fig. 137-8).21

Percutaneous Cholecystostomy

Clinical Relevance

Indications

Contraindications

Equipment

Technique

Anatomy and Approach

Percutaneous Cholecystostomy