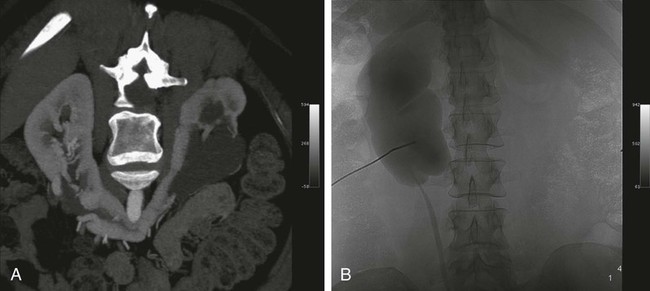

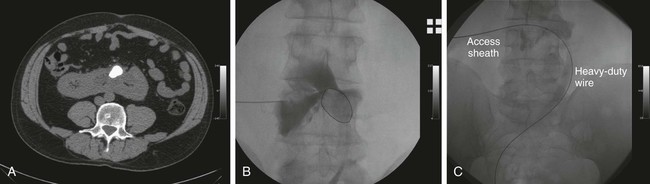

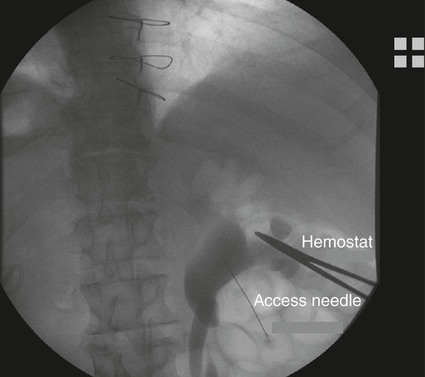

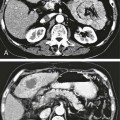

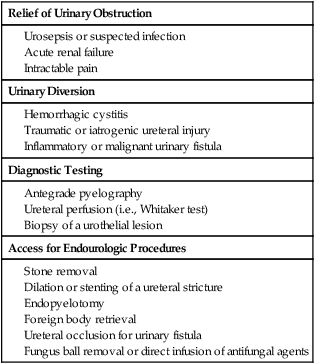

Chapter 146 LeAnn S. Stokes and Steven G. Meranze Since the original description of percutaneous access of a hydronephrotic kidney using a trocar technique and fluoroscopic guidance in 1955,1 percutaneous nephrostomy (PCN) has become the cornerstone of a wide variety of diagnostic and therapeutic endourologic procedures. Percutaneous access to the renal collecting system plays a vital role in the treatment of both adult and pediatric patients with complex urologic problems ranging from malignant obstruction to stone disease to congenital obstruction of the ureteropelvic junction (UPJ). High technical success and low complication rates for PCN make it a valuable tool in the management of urologic disease. Indications for PCN may be grouped into the following general categories: relief of urinary obstruction, urinary diversion, and access for diagnostic and therapeutic procedures (Table 146-1). TABLE 146-1 Indications for Percutaneous Nephrostomy Urinary obstruction is most frequently caused by pelvic malignancy or renal stone disease (Table 146-2). PCN is performed for rapid decompression of an obstructed renal collecting system when retrograde drainage is not feasible, and may be life saving in patients with urosepsis or acute renal failure. PCN may even be preferred over retrograde stenting in patients with obvious infection, because it accomplishes more rapid drainage.2 In patients who have hypotension and leukocytosis, mortality from urosepsis may be reduced from 40% to 8% with emergency PCN.3 TABLE 146-2 Placement of a PCN for urinary diversion may be indicated in several different clinical situations. A urine leak may occur as the result of a traumatic or iatrogenic injury to the renal collecting system, or a leak may arise at a surgical anastomotic site. A urinary fistula may develop in patients with a pelvic malignancy, a pelvic inflammatory process, or a history of irradiation of the pelvis. Another indication for emergency PCN for urinary diversion is the presence of severe refractory hemorrhagic cystitis, which is most commonly due to intravesical chemotherapy or external beam radiation and has a mortality rate of up to 4%.4 In all these scenarios, placement of a PCN alone may not accomplish sufficient urinary diversion to allow healing of the underlying process, and ureteral occlusion may ultimately be necessary.5 Although PCN may still be performed for a wide variety of diagnostic purposes, antegrade pyelography has been replaced in most instances by noninvasive imaging. In a recent series of patients with renal impairment from ureteral obstruction, non–contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) was determined to be the best imaging modality for evaluating calculus disease, and magnetic resonance (MR) urography was thought to be optimal for identifying noncalculous causes of obtstruction.6 In cases in which noninvasive imaging is inconclusive, antegrade pyelography can help determine the severity of an obstruction and can provide very detailed information about stenoses, particularly those at ureteroenteric anastomoses. The access established for antegrade pyelography can also be used for further diagnostic testing, such as brush biopsy of urothelial lesions. Diagnostic PCN can be definitive in other situations in which noninvasive imaging is unreliable. In the setting of chronic obstruction, the finding of mild to moderate cortical atrophy on CT or ultrasound cannot be used to predict whether renal function will recover after decompression, so PCN should be performed before functional testing. If a kidney contributes greater than 20% of overall renal function after percutaneous drainage, it is generally considered worth salvaging. It may also be impossible to determine whether hydronephrosis is due to functional or mechanical obstruction with noninvasive imaging. The Whitaker test, which measures the pressure gradient between the renal pelvis and the bladder, was devised to answer this question (Fig. 146-1).7 This test is most commonly performed either before or after pyeloplasty in patients with UPJ obstruction to determine whether surgical or endourologic treatment is indicated or to determine whether it was successful (Table 146-3). TABLE 146-3 Finally, PCN is frequently performed prior to other interventional procedures, especially in centers with active endourologic surgeons. A wide variety of procedures may be performed via percutaneous access of the kidney, including stone removal, dilation or stenting of a ureteral stricture, endopyelotomy, and foreign body retrieval. Among these procedures, access for treatment of stone disease with percutaneous nephrostolithotomy (PCNL) is by far the most common (Fig. 146-2).2 The strongest contraindication to PCN is severe coagulopathy, with most authors in agreement that an international normalized ratio (INR) less than 1.5 and a platelet count greater than 50,000 should be achieved before the procedure.8–10 Severe hyperkalemia (potassium level > 7 mEq/L) should be corrected with dialysis before the procedure,9 and systolic blood pressure less than 180 mmHg is desirable. If the PCN is elective, antiplatelet agents or anticoagulants should be withheld for 5 days before the procedure when feasible.10 Patients who are allergic to contrast media should receive premedication with either oral or intravenous (IV) steroids. Rarely, patients will have an anatomic variant such as a retrorenal colon that precludes safe percutaneous access to the kidney (Table 146-4). Equipment for PCN is listed in Table 146-5. Image guidance for PCN may be accomplished with ultrasound, CT, fluoroscopy, or some combination of these modalities, most commonly ultrasound and fluoroscopy. For ultrasound-guided access to the renal collecting system, a low-frequency transducer, usually 3.5 MHz, is necessary for sufficient penetration of the retroperitoneal soft tissues to allow good visualization of the kidney. Any multislice CT scanner should provide adequate imaging to identify an appropriate access site and guide needle placement, and combined CT-fluoroscopy can provide real-time guidance for placement of the PCN. If CT-fluoroscopy is not available, it may be necessary to establish needle access to the kidney and then transfer the patient to a fluoroscopy unit for the remainder of the procedure. In the fluoroscopy suite, a rotating image intensifier is extremely helpful because oblique positioning of the tube allows real-time visualization of wire and catheter manipulations while keeping the operator’s hands outside the field of view. Planning the approach for access is the most crucial step in performing successful uncomplicated PCN placement. Before the procedure, any prior studies or cross-sectional imaging should be reviewed to evaluate the anatomy, location, and orientation of the target kidney. Malrotation or malposition of the kidney, duplication of the collecting system, and any cysts, diverticula, tumor, or stones should be noted.11 The location of the lung, liver, spleen, and colon relative to the kidney should be considered, as well as body habitus, such as morbid obesity or spina bifida. The ideal skin entry site is approximately 10 cm lateral to the midline but not beyond the posterior axillary line. If the entry site is too medial, the PCN will cross the paraspinal musculature and make dilation of the tract more difficult and the tube more painful for the patient, and an entry site that is too lateral increases the risk of colonic perforation. The tract should avoid the inferior margin of the rib to decrease the risk of injury to an intercostal artery. If a supracostal approach is necessary for treatment of an upper pole stone, the risk of injury to lung, liver, or spleen is significantly less in the T11-T12 interspace than in the T10-T11 interspace.12 Numerous techniques for image-guided PCN placement have been described. The renal collecting system can be accessed using a single-stick or double-stick method with ultrasound, fluoroscopy, or CT, alone or in combination. The single-stick method is more likely to be possible in patients with moderate to severe hydronephrosis, because it facilitates visualization of a calyx for direct access. A double-stick method is useful when the collecting system is not dilated, making it initially more difficult to access a calyx. In this technique, the first needle is used to access and opacify the collecting system so a more appropriate site for definitive access can be targeted (Fig. 146-3). There is reportedly no difference in technical success and complication rates for a single- versus double-stick technique.3,13 Occasionally, PCN will be necessary in a patient who has a nondilated system, which can be seen in the setting of a ureteral leak or fistula, hemorrhagic cystitis, or nondilated obstruction. The pathophysiology of obstruction without hydronephrosis is not well understood, but reversal of acute renal failure after PCN in a nondilated system has been well documented.14 A double-stick technique for fluoroscopically guided access to a nondilated system has been described.15 Intravenous contrast material is administered to opacify the collecting system, and a 22-gauge needle is quickly advanced directly into the renal pelvis. This needle can be used to distend the collecting system with a small amount of contrast material and air, then PCN can be performed as described previously. If the patient is in renal failure and IV contrast material cannot be given, ultrasound guidance can be used to access the renal pelvis as well.

Percutaneous Nephrostomy, Cystostomy, and Nephroureteral Stenting

Percutaneous Nephrostomy and Nephroureteral Stenting

Indications

Relief of Urinary Obstruction

Urinary Diversion

Diagnostic Testing

Access for Endourologic Procedures

Benign

Malignant

Intrinsic

Stone

Urothelial tumor

Clot

Sequestered papilla

Fungus ball

Extrinsic

Postoperative scar tissue

Pelvic tumor

Surgical ligature

Adenopathy

Crossing vessel

Retroperitoneal fibrosis

Pressure Gradient

Result

<15 cm H2O

Normal

15-22 cm H2O

Indeterminate

>22 cm H2O

Positive for upper urinary tract obstruction

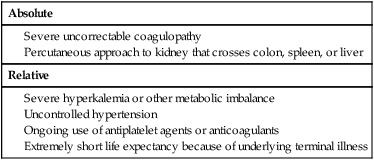

Contraindications

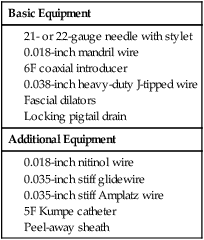

Equipment

Technique

Anatomy and Approach

Technical Aspects

Percutaneous Nephrostomy Placement in a Nondilated Collecting System