Peripheral Vascular Injury

Christopher L. Smith

Peripheral vascular injury occurs in 25-35% of patients with penetrating trauma. Arterial injury carries major morbidity and complications and further diagnostic imaging is indicated when a projectile’s path is suspected to be near a major vessel.

Etiology.

Peripheral vascular injury is most commonly the result of penetrating trauma, but it may also occur with blunt trauma, especially if there is an associated fracture or joint dislocation. For example, in 50% of cases of posterior knee dislocation, there is a popliteal artery injury making further diagnostic evaluation mandatory in this setting. Catheter angiography can also be a cause of arterial injury.

Arterial injury can lead to arterial thrombosis or can result in an expanding hematoma, which can compress adjacent blood vessels and cause peripheral ischemia. Sequelae of arterial injury include formation of a pseudoaneurysm or development of an arteriovenous fistula. Pseudoaneurysms can continue to expand and rupture at any time. With active hemorrhage peripheral arterial injury can even lead to exsanguination and death.

Symptoms and Signs

Signs of hemorrhage. Pulsatile external bleeding, an expanding or pulsating hematoma, unexplained hypotension with Hct less than 30% or rapid Hct drop (15% drop within 2 hours).

Signs of ischemia. Severe pain, loss of peripheral pulses, progressive swelling of an extremity, coolness or pallor of an extremity, cyanosis, poor capillary refill.

Altered flow. Bruit, palpable thrill (with arteriovenous fistula), ipsilateral dilated veins (with arteriovenous fistula).

Associated deficits. Loss of peripheral neurologic function, fracture, joint dislocation (especially the knee).

Physical Examination.

It is vital to palpate the appropriate peripheral pulses, both proximal and distal: carotid in the neck; axillary, brachial, radial for the upper extremity; and femoral, popliteal, posterior tibial, and dorsalis pedis for the lower extremity. Auscultation should be performed to assess for murmurs and bruits. A standard clinical Doppler is often useful for examining the distal pulses and especially when peripheral pulses are nonpalpable.

If physical signs are present, then the rate of positive findings with further diagnostic imaging increases dramatically. For example, arteriography demonstrates arterial injury in 90% of cases with absent distal pulses and in 50% of those with diminished peripheral pulses.

Indications.

The use of computed tomographic angiography (CTA) for the evaluation of lower extremity vascular pathology has been well described in the literature. This modality is useful in the evaluation of both peripheral vascular disease and traumatic

arterial injuries of the lower and upper extremities. Recently many have suggested that CTA is preferable to conventional arteriography for the initial evaluation of traumatic arterial injuries because it is noninvasive, rapid to perform, nearly universally available, and provides information about surrounding structures/injuries.

arterial injuries of the lower and upper extremities. Recently many have suggested that CTA is preferable to conventional arteriography for the initial evaluation of traumatic arterial injuries because it is noninvasive, rapid to perform, nearly universally available, and provides information about surrounding structures/injuries.

Protocol.

Best performed using multidetector computed tomography (CT) (at least 16 rows). The examination is typically performed with the smallest slice thickness available to improve the resolution and to allow for multiplanar and 3D reconstructions. Studies are performed with nonionic intravenous contrast usually injected at rate of 3 mL/second. Scan delay to data acquisition is approximately 25 seconds with scans obtained in a proximal to distal orientation. Scans of the upper extremities are performed with the patient’s arms stretched over the chest, by the side, or extended over the head. Lower extremity scans can be performed with the patient in the normal supine position. If possible, symmetry should be maintained because comparison is often useful. Once the data sets are generated, they are sent to a freestanding workstation where maximum intensity projection (MIP), multiplanar reconstruction (MPR) and 3D maps are evaluated.

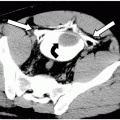

Possible Findings (Fig. 51-1)

Arterial occlusion. Nonvisualization of the artery especially when compared to adjacent arteries in the same and contralateral extremity. It is important to compare nearby arteries in the same extremity to ensure that the nonvisualization is not a result of a poor contrast bolus. Occasionally, a low-density intraluminal-filling defect that represents a thrombus can be seen.

Arterial dissection. Often an intimal flap will be seen. The false lumen may or may not fill with contrast depending on the presence of thrombosis and the chronicity of the injury. A sharply tapering, often angulated artery, which then becomes occluded, can also be a sign of a dissection.