Clinical Considerations

Patients with soft tissue infections of the oropharynx and neck commonly present to the emergency department and other frontline medical providers. Peritonsillar abscess (PTA) is the most common deep infection of the neck and face. PTAs develop from tonsillitis, which progress to peritonsillar cellulitis and then onto abscesses. Although peritonsillar cellulitis and PTAs may be considered a spectrum of disease, they are important to differentiate as their definitive management differs. Peritonsillar cellulitis is treated with antibiotics, analgesics, and at times steroids for symptom management, whereas PTAs may require aspiration or incision and drainage (I&D).

It can be difficult to differentiate between cellulitis and abscess by history and physical alone, as signs and symptoms may be nonspecific and unreliable. One distinguishing feature for PTAs is that they often develop unilaterally, whereas tonsillitis usually develops bilaterally. However, studies have shown that clinical evaluation by otolaryngologists is only 78% sensitive and 50% specific for identification of PTA. Historically, patients presenting with sore throat, fever, chills, and/or peritonsillar erythema and edema were managed with a diagnostic needle aspiration of the peritonsillar swelling to search for pocket(s) of purulence. This blind aspiration poses significant risks, including carotid artery injury (as the carotid artery is frequently within millimeters of the area of swelling), hemorrhage, insufficient aspiration leading to recurrence of the PTA, and false-negative aspirations in 10% to 24% of cases. Today, the gold standard for identifying a PTA is computed tomography (CT) of the neck with intravenous (IV) contrast. Although CT is the gold standard, there is growing concern for radiation exposure, especially in adolescents and young adults (who have the highest incidence of PTAs). CT is also costly and time consuming. For these reasons, medical specialists are turning to ultrasound to help identify PTAs.

The use of intraoral ultrasound for the diagnosis of PTA was first described in 1993. This imaging modality has the advantage of being rapid (done at the bedside), noninvasive, lacking in radiation exposure, and usually well tolerated. It may be used to detect occult abscesses and localize the optimal site for aspiration or I&D. Studies report a sensitivity of 89% to 100% and specificity of 83% to 100% in detecting abscess compared with CT, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or surgical follow-up.

Anatomy

Posterior oropharyngeal anatomy is complex and potentially hazardous during PTA management, so it is important to have a clear understanding of regional anatomy.

The palatine tonsils are ovoid masses composed of lymphoid tissue that reside in the lateral walls of the oropharynx between the anterior and posterior tonsillar pillars. The tonsils lie in the depression between the palatoglossal arch anteriorly and the palatopharyngeal arch posteriorly. Each tonsil is surrounded by a capsule ( Fig. 3.1 ). Each tonsil is composed of a medial and lateral surface and an upper, middle, and lower pole. A PTA forms between the palatine tonsil and its capsule, rather than within the tonsil itself. As an abscess progresses, it may involve the surrounding anatomy and even penetrate the carotid sheath, which is situated posterolateral to each tonsil. Another complication of pharyngitis is Lemierre’s syndrome, a suppurative thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein. This complication can be accompanied by bacteremia or septic emboli and is most commonly caused by the gram-negative anaerobe Fusobacterium necrophorum . This condition should be treated with penicillin, clindamycin, or a third-generation cephalosporin, as macrolide resistance is high in F. necrophorum .

When utilizing bedside ultrasound in the posterior oropharynx, one can visualize several structures, including the palatine tonsil, margin of the bony hard palate, styloid process of the temporal bone, medial pterygoid muscle, various fascial planes, internal jugular vein, and internal carotid artery. When evaluating a possible PTA with ultrasound, it is imperative to identify the location of the carotid artery. The carotid artery courses anterior to the jugular vein within the carotid sheath ( Fig. 3.2 ). It is normally located posterolateral to the tonsil and within 5 to 25 mm of the PTA.

Preparation and Technique for Intraoral Ultrasound Evaluation

Probe

When evaluating for a PTA, it is best to use a high-frequency probe. We recommend the 5- to 13-MHz curved array endocavitary probe. Other probe options include the 5.0- to 7.5-MHz linear array or dedicated flexible endoscopic transducer. Prepare the probe as follows:

- 1.

Choose the appropriate probe. Ensure it has been sterilized since its most recent use.

- 2.

Apply ultrasound gel to the tip of the probe.

- 3.

Sheath the probe in a probe cover (nonlatex glove if patient has a latex allergy).

- 4.

Securely fasten the probe cover with an elastic band or by the built-in retaining bar.

- 5.

Gently remove any air bubbles in the gel at the tip of the probe.

- 6.

On the ultrasound machine, set the initial depth to 5 cm and the probe to the highest frequency available.

After use, sterilize the probe according to institutional policy.

Premedication

Although evaluation for PTA by ultrasound is noninvasive, the pressure of the probe on the swollen tissue can cause pain and anxiety, as well as trigger the patient’s gag reflex. Hence, these procedures often proceed more smoothly with premedications. Consider an IV anxiolytic or light analgesic if the patient is anxious or trismus is present. Also consider an IV steroid (e.g., dexamethasone) to help with inflammation and symptom control before the procedure. Finally, consider nebulized, atomized, viscous, or topical lidocaine for local anesthesia. If you are concerned the patient may not be sufficiently cooperative, consider a bite block for protection.

Technique

- 1.

Position the patient in a seated or upright position. Place a pillow or stacked towels behind the patient’s head for comfort.

- 2.

Carefully place the probe on the tonsil in the transverse plane, with the indicator to the patient’s right. The probe should contact the glossopalatine arch (anterior pillar) to visualize the lateral tonsil.

- 3.

Operators often need to hold the probe with both hands for stability. Place your dominant hand on the probe handle and your nondominant hand on the probe shaft abutting the perioral area. Alternatively, consider allowing the patient to place their hand on top of the operator’s dominant hand. This allows the patient to help control insertion and pressure, as well as to remove the probe if their gag reflex may trigger emesis ( Fig. 3.3 ).

Fig. 3.3

Endocavitary probe in dual hold by practitioner and patient to avoid gag reflex. Probe indicator is to the patient’s right.

- 4.

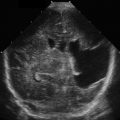

Identify the tonsil. When not inflamed, the tonsil is an ovoid structure approximately 2 cm in diameter. As the tonsil is a solid organ, it will appear as a homogeneous, hypoechoic structure distinct from surrounding tissue on ultrasound ( Fig. 3.4 ).