Fast for 4–6 h prior to scan

Screen for diabetes, insulin injection

Finger stick to check fasting glucose level prior to injection (should be <200 mg/dL)

Inject intravenous tracer (10–20 mCi, generally 10–12 mCia)

Image 45–60 min after injection

Void bladder prior to imaging

Image from skull base to mid-thigh

CT (either low-dose or diagnostic) done first

Emission scan 5–6 fields, 3 min per field of view

6.1 Physiologic Distribution and Variants

FDG uptake also occurs in nonmalignant tissues, most prominently the brain and heart. Lesser activity is seen in liver, spleen, and bone marrow. FDG is excreted by the kidneys, so prominent uptake is seen in the kidneys, ureters, and bladder. In females, certain physiological conditions of the reproductive system and benign lesions may be associated with increased uptake of FDG. Functional uptake in endometrium related to cyclic changes (Fig. 6.1) and menstruation (Fig. 6.2) is the most common cause of intense activity seen in the uterus in women without known malignancy of the reproductive tract [1, 2].

Uptake may be seen in the ovaries related to maturing or growing follicles (Fig. 6.3), especially in younger or premenopausal women [3]. Increased ovarian uptake of FDG in postmenopausal patients would raise the suspicion for malignancy (Fig. 6.4). Though high uptake suggests malignant disease, there is significant overlap in uptake for benign versus malignant lesions. In a reported study, a standardized uptake value (SUV) of 7.9 in ovary separated benign from malignant uptake with 57 % sensitivity and 95 % specificity [4]; an average SUV of 9.1 ± 4 was seen in malignant lesions versus 5.7 ± 1.5 in nonmalignant conditions. It is recommended that uptake in uterus or ovaries be correlated with history and corresponding CT scans. Other benign causes of uptake may be related to functional cyst, corpus luteum, adenoma, dermoid cyst, endometriosis, inflammation, and teratoma, reported to show variable uptake of FDG (Figs. 6.5 and 6.6) [3–6]. Uterine uptake can vary during the various phases of the menstrual cycle. Uterine fibroids are also a common benign cause of uptake of FDG in the uterus, generally appearing as low-grade, heterogeneous uptake (Fig. 6.7) but sometimes appearing as prominent activity; correlation with CT findings can help delineate the fibroids (Fig. 6.8) [6, 7]. Contamination may cause false focal uptake and should be ruled out (Fig. 6.9) [8].

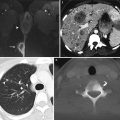

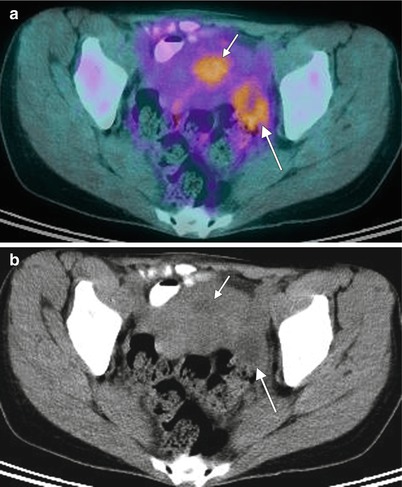

Fig. 6.1

Physiologic uptake in the endometrium related to cyclic changes. A 44-year-old premenopausal woman had an FDG PET-CT scan, performed to evaluate lung nodules. Transaxial fused images (a) show mild uptake in the region of the uterus (short arrow) and left adnexa (long arrow) with standardized uptake values (SUVs) of 3.6 and 3.2 respectively. Details on menstrual history revealed that this imaging was performed 17 days after the last menstrual cycle. There was no evidence of malignancy in the uterus or adnexa on CT (b). The activity reflects physiologic endometrial activity and uptake in the follicle in the left adnexa (b). The uterus had fibroids that did not show FDG uptake

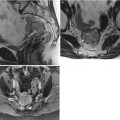

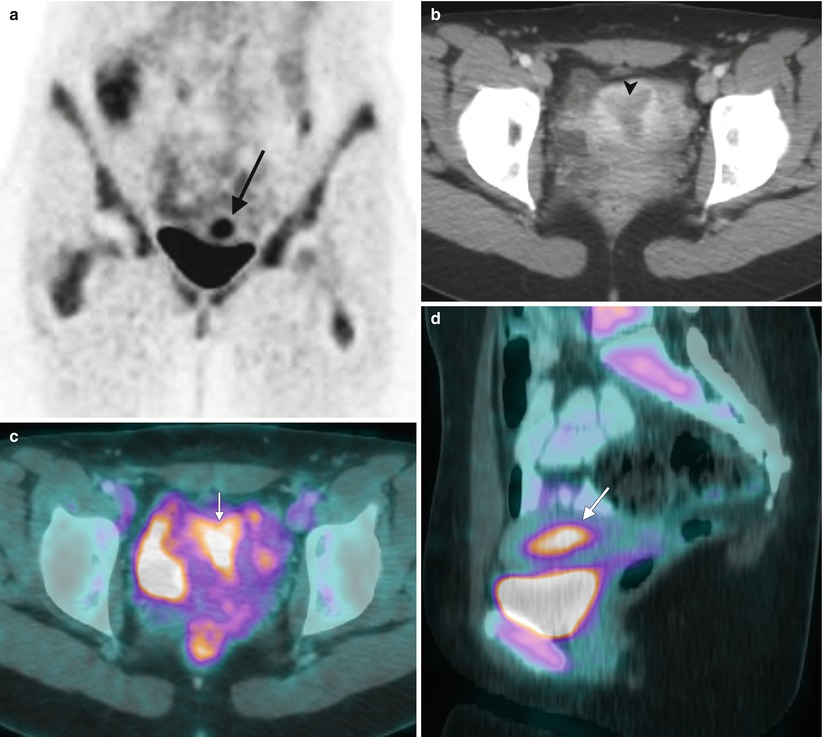

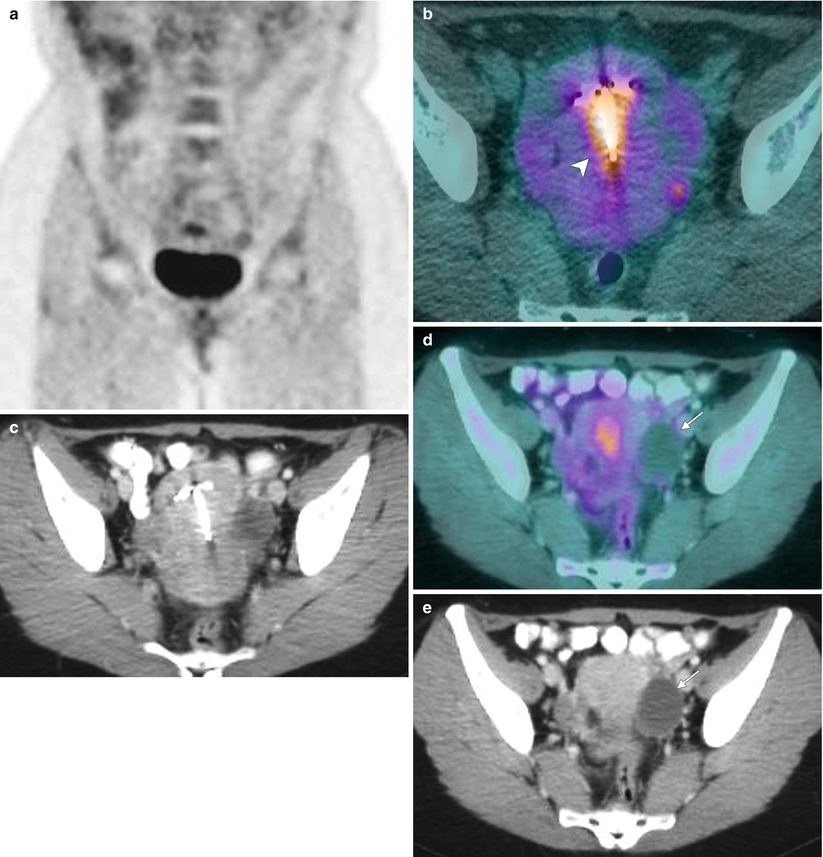

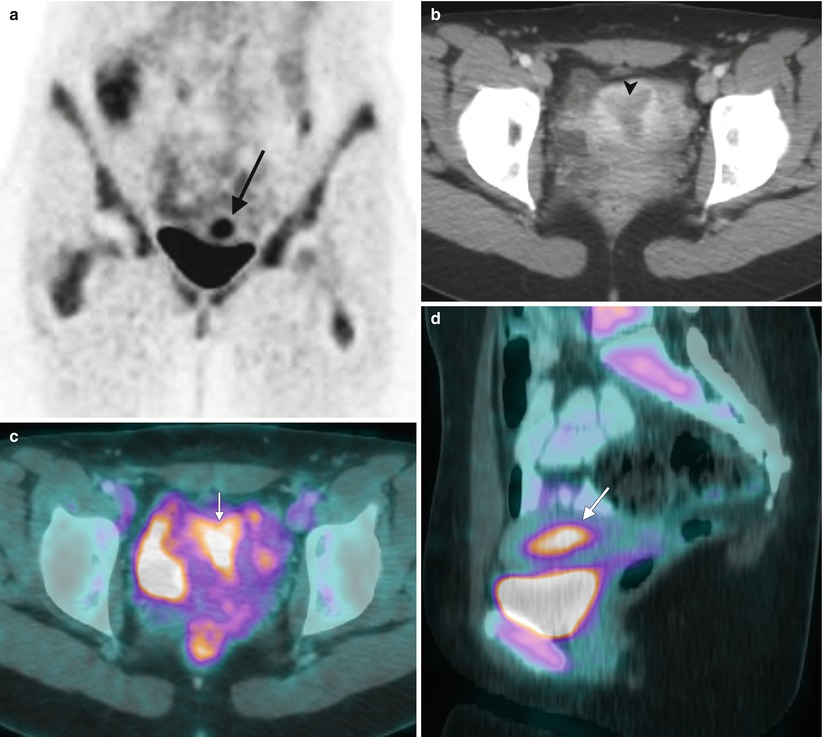

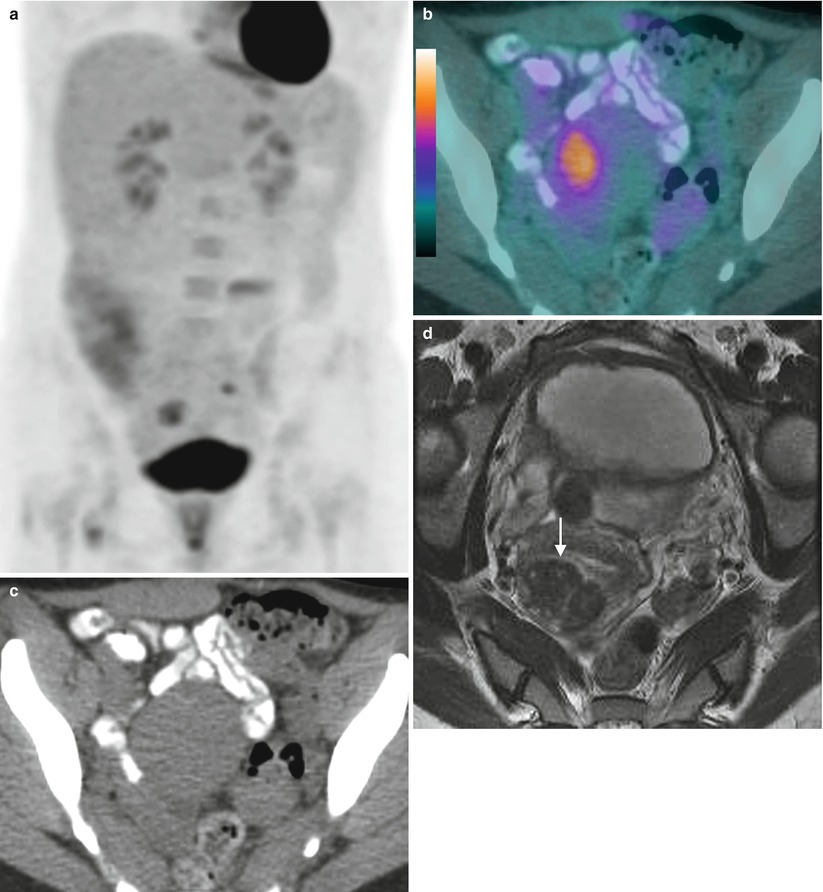

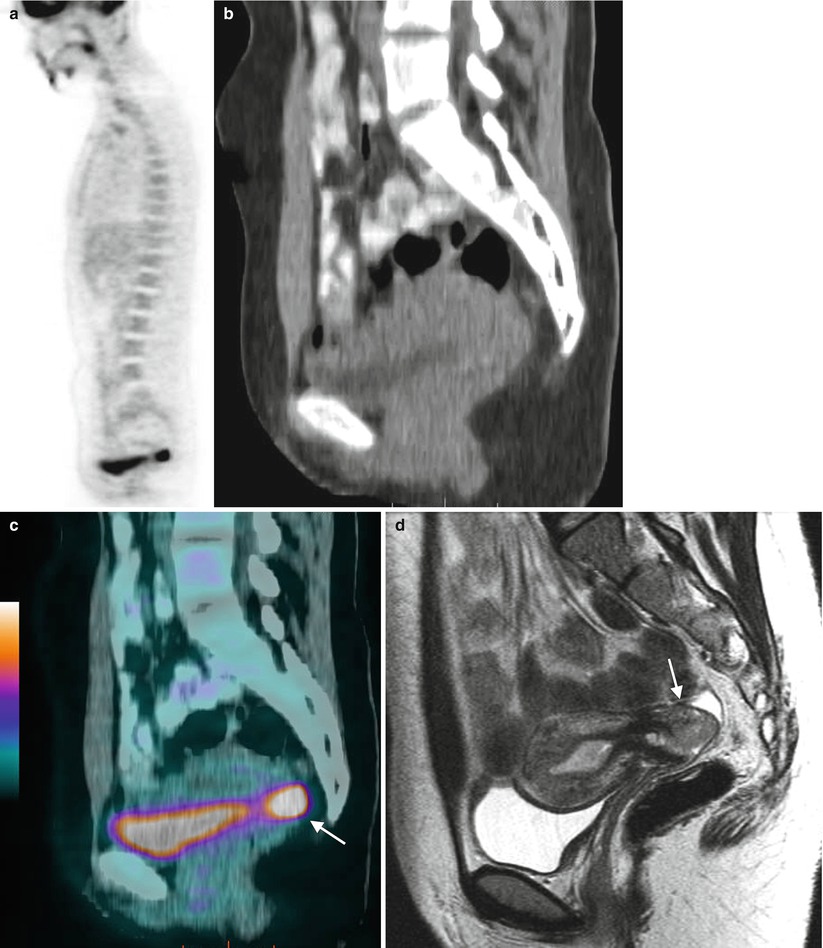

Fig. 6.2

Physiologic FDG uptake in the uterus with active menstruation. This FDG PET/CT scan of an 18-year-old woman was obtained for restaging of nongynecologic malignancy. Coronal images (a) show increased activity in the pelvis, superior to the bladder (long black arrow), which localized to the uterine cavity on a CT image (b) that showed a hypoenhancing central area of endometrium (arrowhead). On the axial (c) and sagittal (d) fused FDG PET-CT images, intense FDG uptake is seen in the uterine cavity (short white arrows), with a standardized uptake value (SUV) of 6.6. The patient was actively menstruating at the time of the scan, which was likely the cause of increased activity. There was no known malignancy of the uterus at this time or in followup. Uptake in the uterus secondary to menstruation is generally high-intensity within the central uterus and diffuse along the endometrium. It can be distinguished from other causes of uptake such as uterine fibroids, which may produce activity that is eccentric in location and of variable intensity; often FDG activity in patients with fibroids is heterogeneous and of low grade or nonexistent

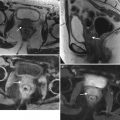

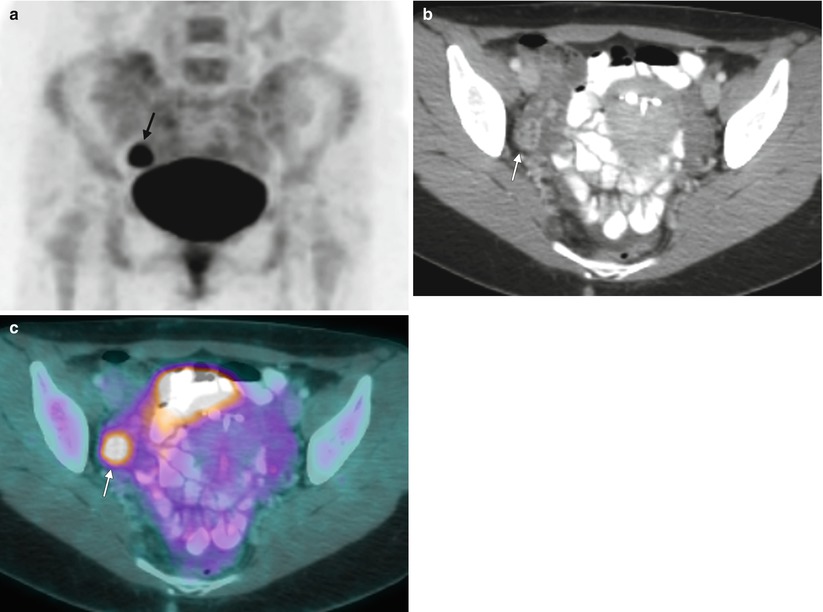

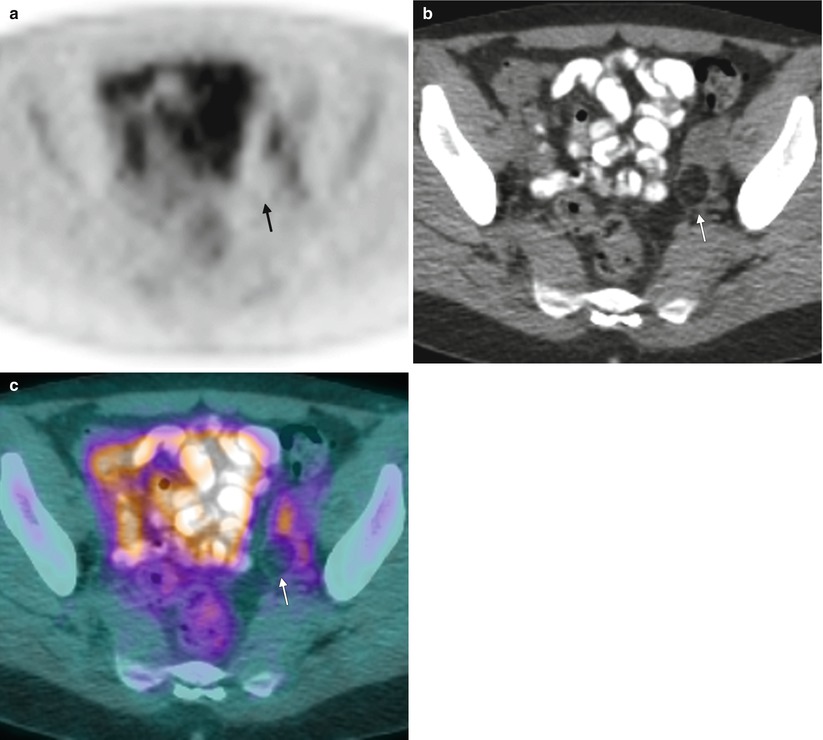

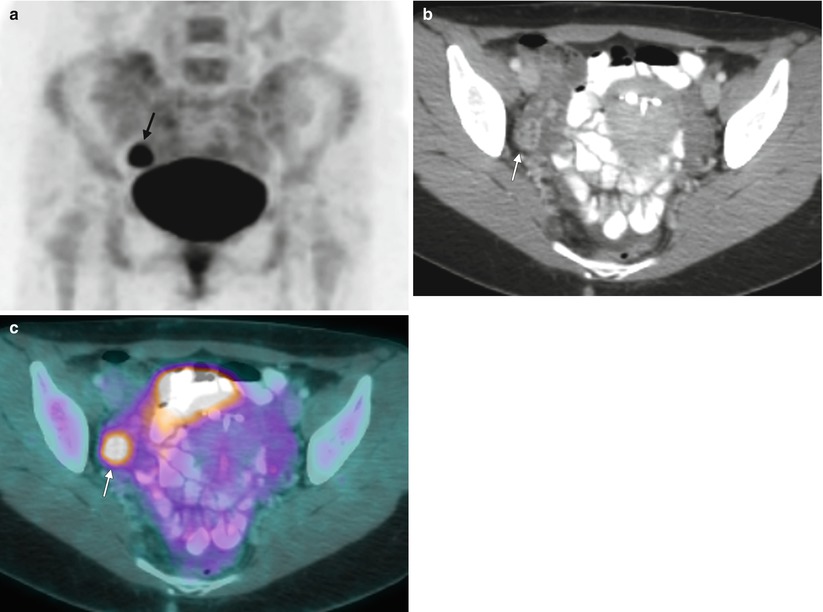

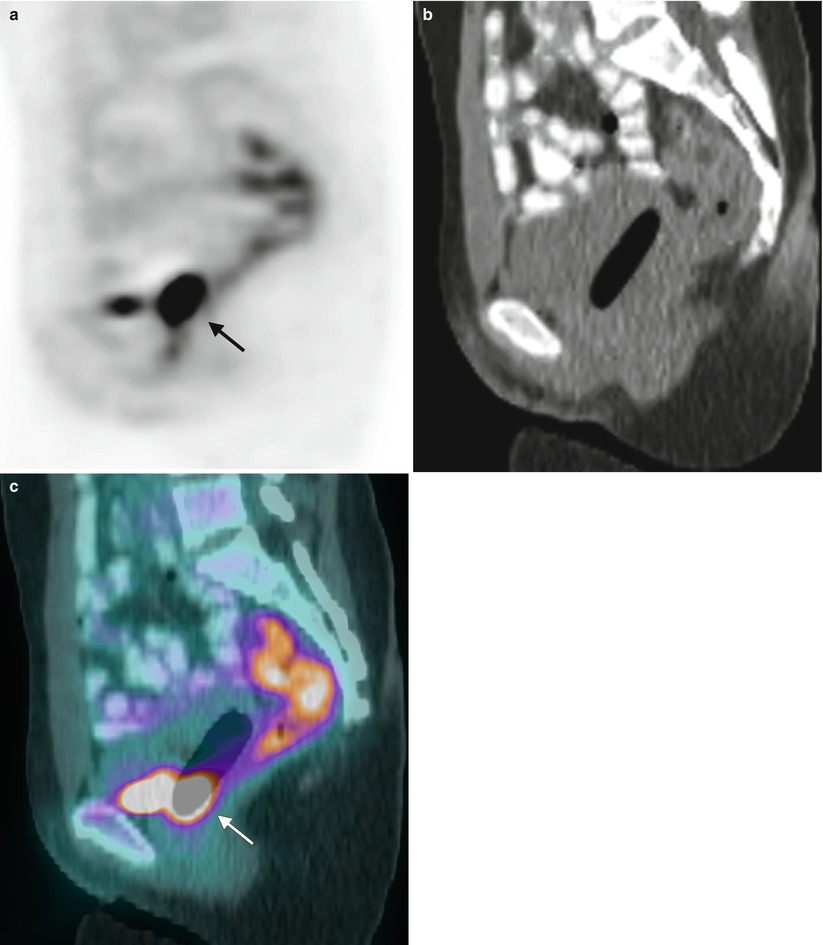

Fig. 6.3

Physiologic ovarian uptake in a young, premenopausal woman. This FDG PET-CT scan of a 27-year-old woman was obtained for restaging of a nongynecologic malignancy. The maximum intensity projection (MIP) PET image (a) shows an area of focal FDG uptake in the right pelvis just above the bladder (arrow). A contrast-enhanced axial CT image (b) delineates rimlike enhancement within the right adnexa. The fused FDG PET-CT image (c) confirms that the prominent focal activity is within the right adnexa along the enhancement in the right ovary, consistent with a corpus luteum. The patient was imaged on day 21 of her menstrual cycle. Corpus luteum can show prominent FDG uptake, in this case with a standardized uptake value (SUV) of 8.0

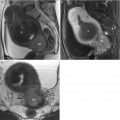

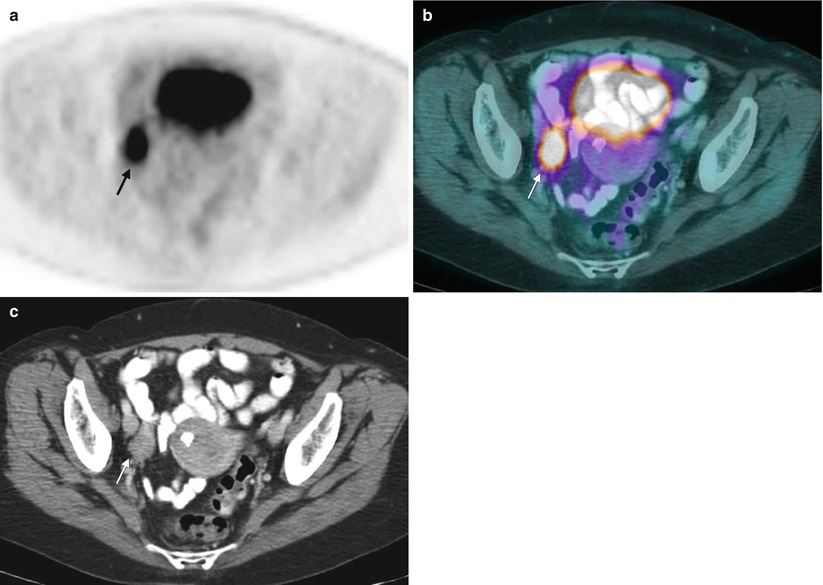

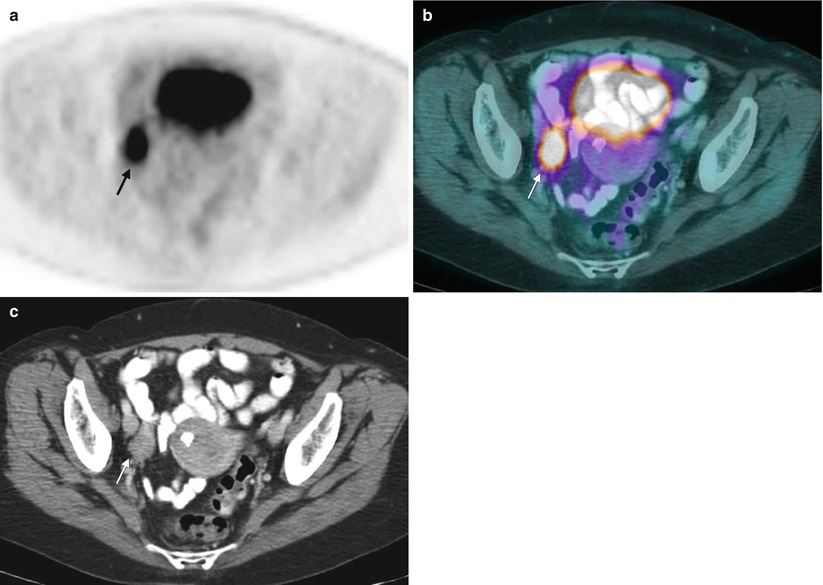

Fig. 6.4

Ovarian uptake in a postmenopausal woman. PET-CT imaging of this 61-year-old woman was obtained for nongynecologic malignancy. A transaxial PET image (a) shows increased activity in the right pelvis (arrow). Transaxial fusion PET-CT (b) and CT (c) images show uptake localizing to the right ovary (arrows). The SUV was 8.9. Such uptake is considered unusual and nonphysiologic in a postmenopausal woman. Further evaluation revealed malignant involvement of the right ovary. Increased uptake in postmenopausal women should always be investigated to exclude malignancy

Fig. 6.5

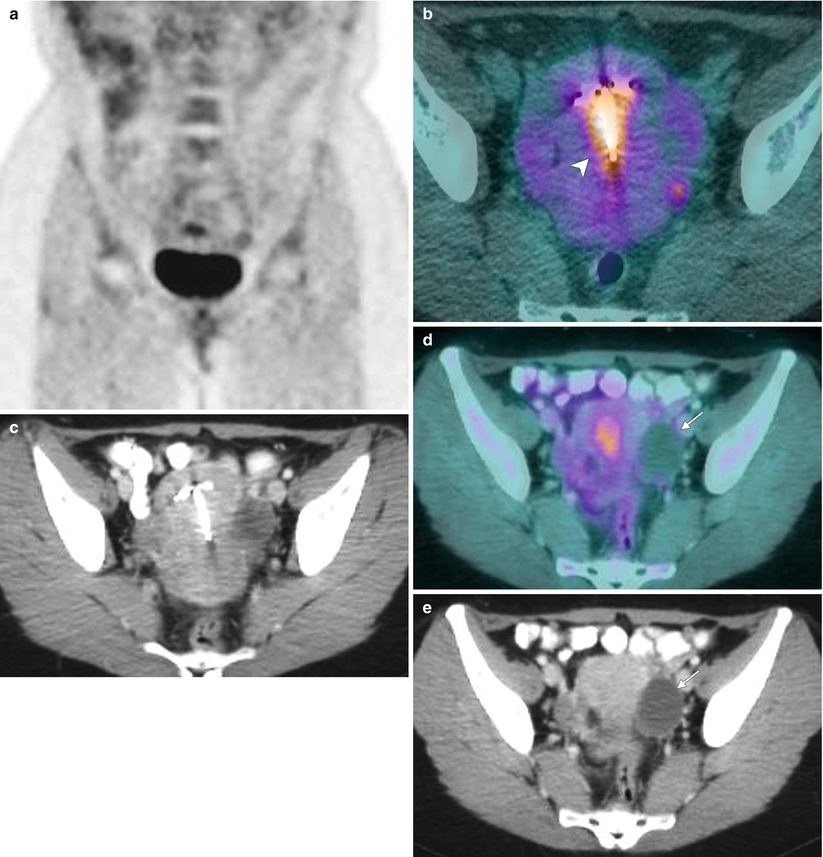

Physiologic uptake in the uterus and a non–FDG-avid functional ovarian cyst. These images show a 34-year-old woman with nongynecologic malignancy. The coronal MIP PET image (a) shows focal FDG uptake in the pelvis just above the bladder. The fused axial FDG PET-CT image (b) and CT image (c) show uptake corresponding to the uterine cavity (arrowhead) with an IUD in situ. Uptake in the uterus may be related to physiologic endometrial changes or reactive changes to an IUD. No increased uptake is seen in left ovary cyst (arrows) consistent with a physiologic functional cyst (d, e).

Fig. 6.6

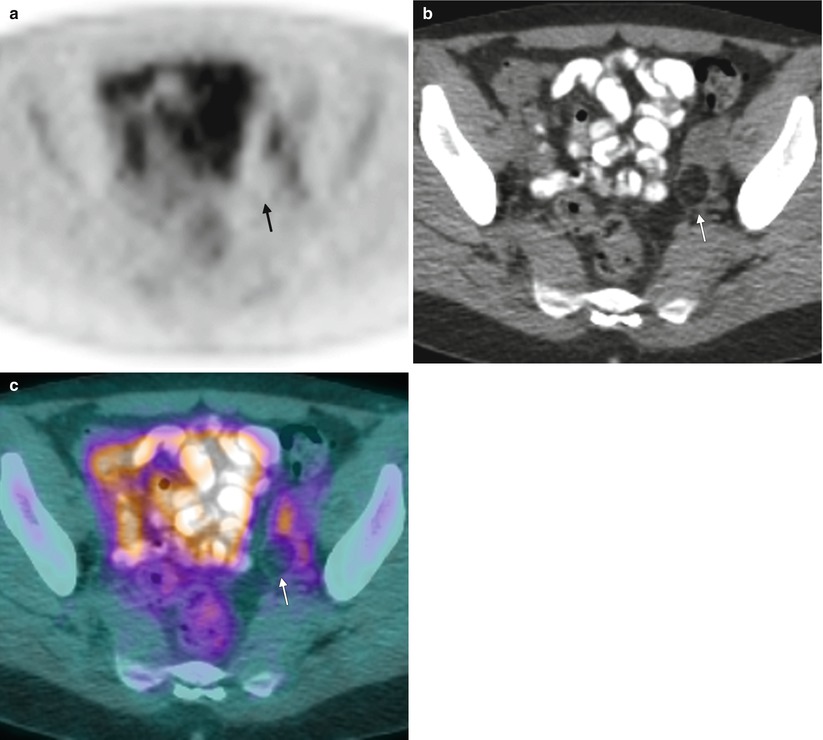

FDG PET and benign lesions of the adnexa. In this 35-year-old woman, the axial PET image (a) shows no increased FDG uptake in the region of the left adnexa. On the contrast-enhanced axial CT image (b), there is a small, hypoattenuating mass within the left ovary (arrow). On the fused FDG PET-CT image (c), there is no increased FDG activity within this lesion in the left ovary. Fat-containing lesions within the ovaries are most commonly ripe teratomas, which typically do not take up FDG. Rare cases of uptake in mature teratomas and malignant transformation have been reported

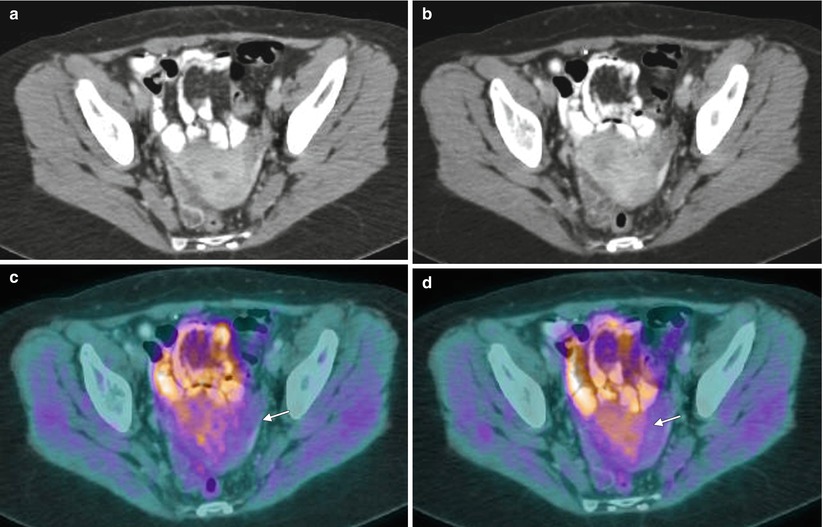

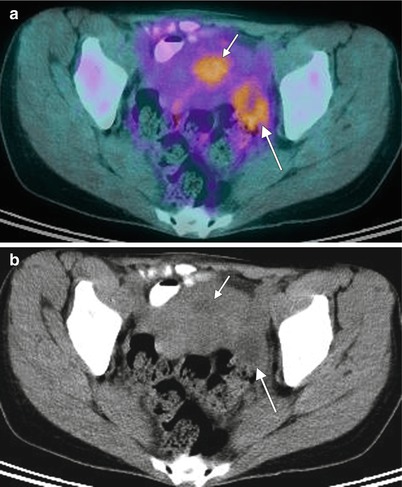

Fig. 6.7

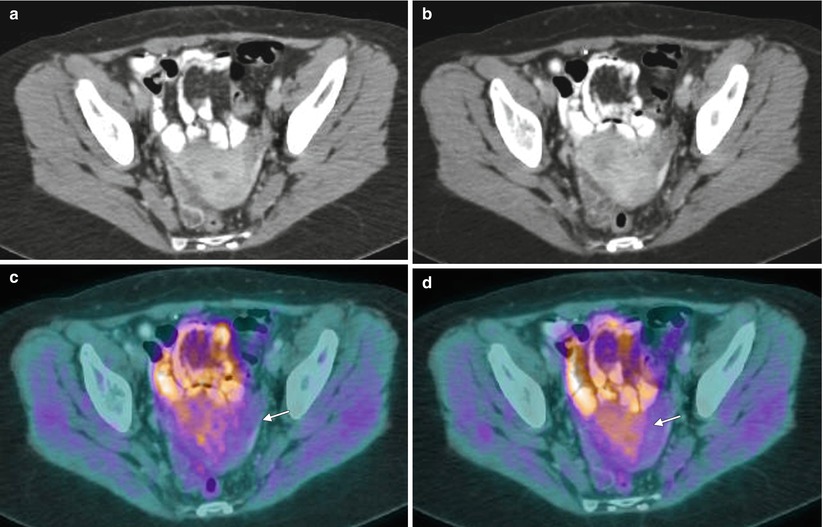

FDG uptake in uterine fibroids: mild heterogeneous activity. A 35-year-old woman with breast cancer was imaged for evaluation of recurrent disease. CT images (a, b) of the pelvis showed uterine fibroids that show only minimal, heterogeneous activity of FDG (SUV 2.7), as seen on fused PET-CT images (c, d) (arrow)

Fig. 6.8

Uptake in uterine fibroids: intense activity. A MIP PET image (a) of a 45-year-old woman observed for breast cancer with FDG PET-CT shows uptake in the pelvis. A fused PET-CT image (b) shows increased focal FDG activity in the uterus, corresponding to the fibroid (SUV 6.5) (c, d). Uterine fibroids have a higher incidence of increased FDG activity in premenopausal women (10.4 %) than in postmenopausal women (1.2 %). The FDG activity can be highly variable, with reported maximum standardized uptake values (SUVmax) up to 16. The predominance of uptake in premenopausal women suggests hormonal dependency. Vascularity, cellularity, and proliferation rate also have been reported to influence the FDG uptake of leiomyomas [6, 7]

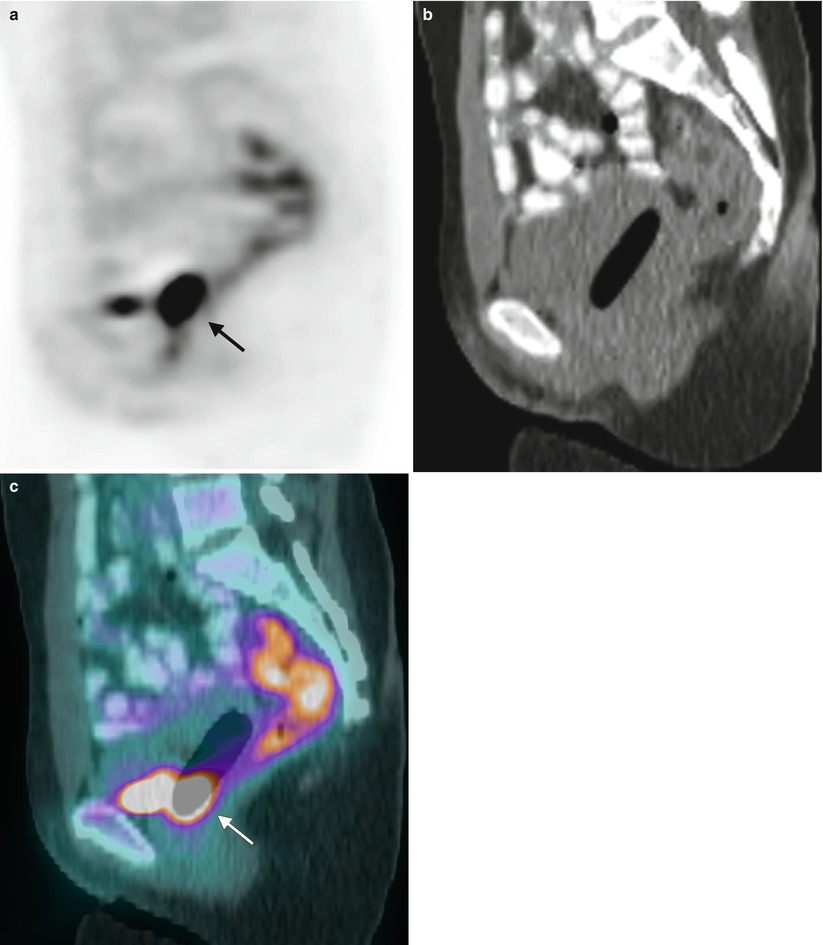

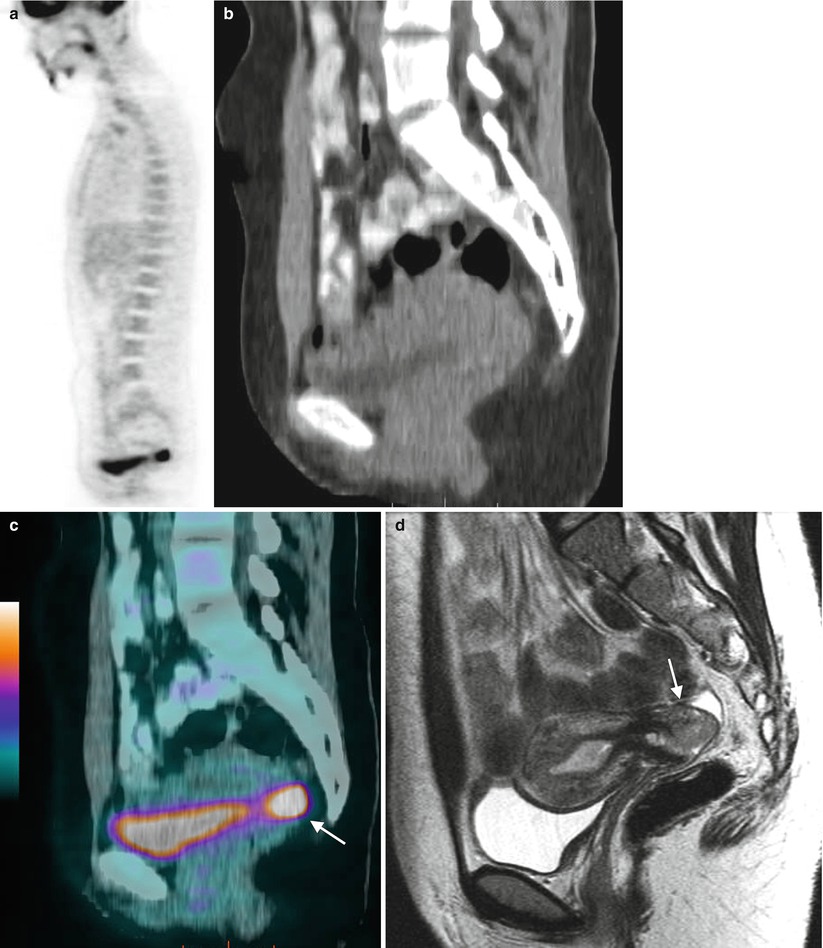

Fig. 6.9

Uptake in vagina secondary to tampon contamination. A 26-year-old woman was examined on day 5 of her menstrual cycle. The sagittal PET image (a) shows a focal FDG uptake behind the bladder (arrow) localizing to the vagina (SUV 21). The sagittal CT scan (b) illustrates an intravaginal tampon. The fused sagittal FDG PET-CT image (c) shows concentration of the FDG activity in the base of the tampon, most likely due to urine contamination [8]. The uptake is generally concentrated predominantly in the inferior portions and is similar to the uptake in the urine in the bladder

6.2 Cervical Cancer

Most primary cervical cancers concentrate FDG, especially those with poorly differentiated and squamous histology (Figs. 6.10 and 6.11). For staging, FDG PET-CT is useful in assessing pelvic or extrapelvic nodal involvement and detecting distant metastases (Figs. 6.12 and 6.13). This information is useful in planning the primary treatment of the patient, including surgery, radiation therapy, or both. Sensitivity and accuracy in detecting lesions are higher for advanced disease and are low for early-stage disease, up to stage 1A2 or 2A [9–11]. The primary advantage of FDG PET-CT is the detection of unknown distant metastases and lymph node metastases that are benign by mere size criteria (Fig. 6.14). The use of FDG PET imaging for routine staging prior to radical hysterectomy and pelvic lymph node dissection is still controversial, though the high specificity and negative predictive value of PET may be helpful in appropriate treatment planning [12, 13]. Low-volume disease and micrometastasis are the most frequent causes for false negative FDG PET findings. The use of larger scanning areas can also detect extra-abdominal disease (Fig. 6.15) [14]. Involvement of para-aortic metastasis is linked to prognosis and progression-free survival [15].

FDG PET helps in early detection of recurrent disease, evaluation of distant lesions, and followup of treatment (Fig. 6.16). The overall sensitivity for detection of recurrence was reported to be as high as 86 %, with specificity of 94 %; the positive predictive value was 85.7 % and the negative predictive value was 86.7 % [16]. It also is useful for assessing response to chemoradiation therapy (Fig. 6.17). Early metabolic response can be assessed, whereas anatomic changes may lag or may be difficult to assess.

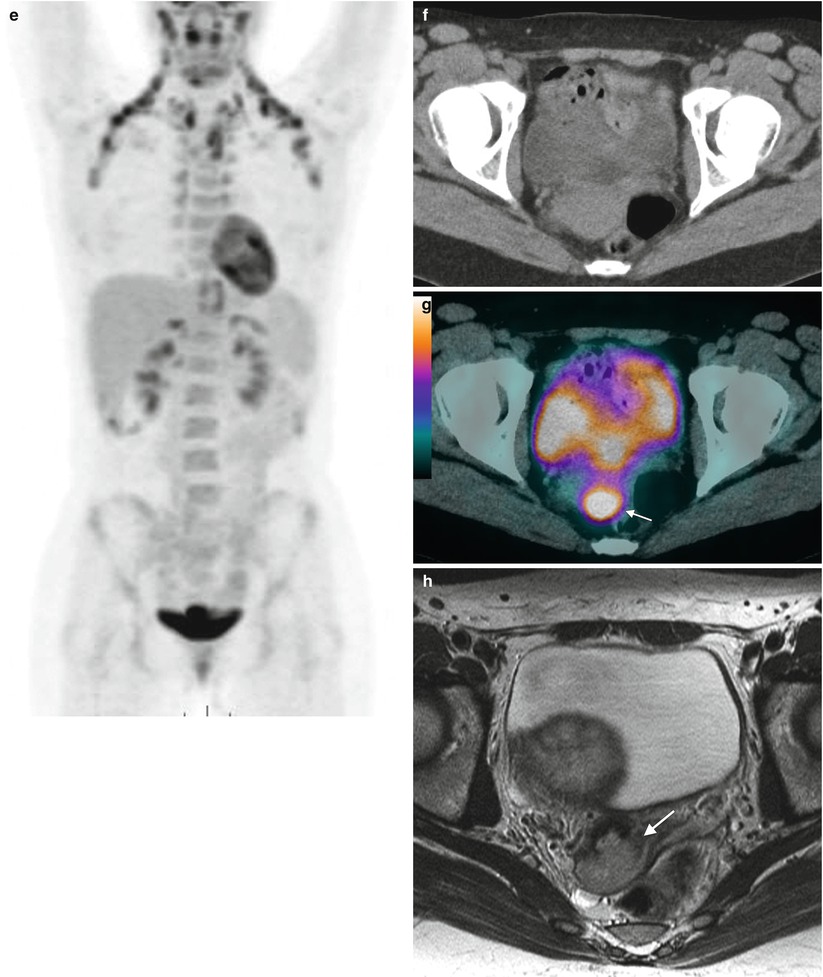

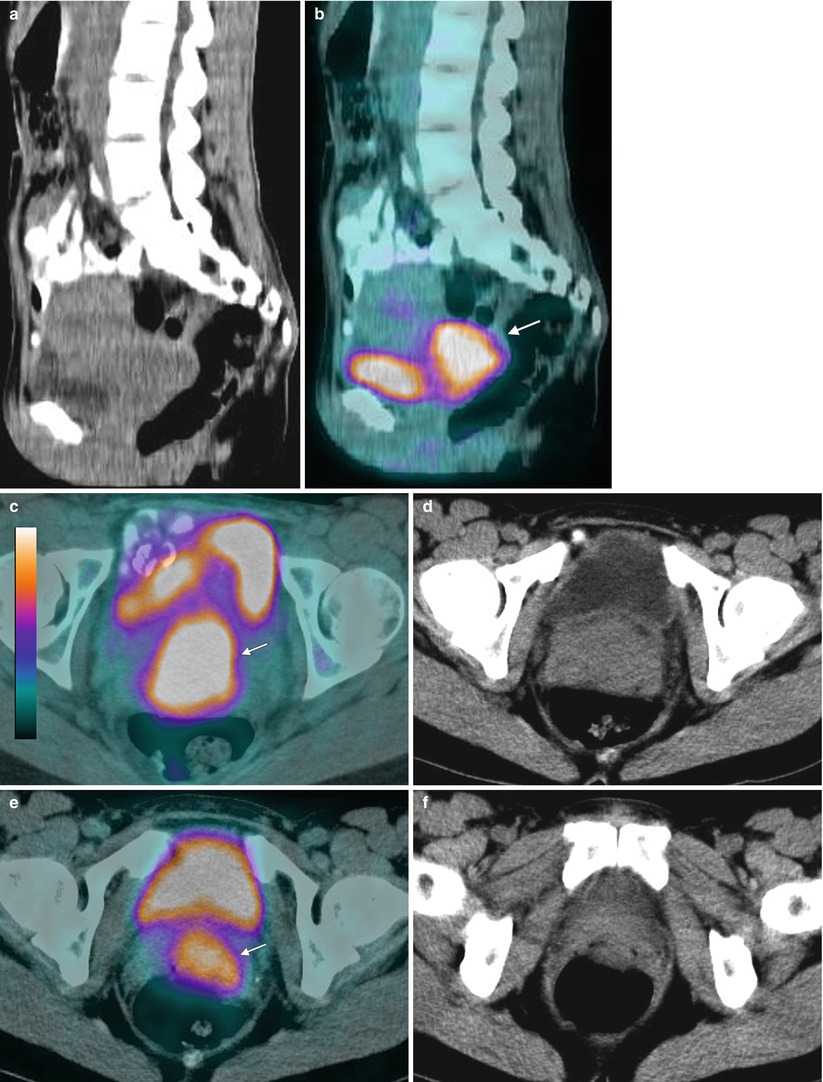

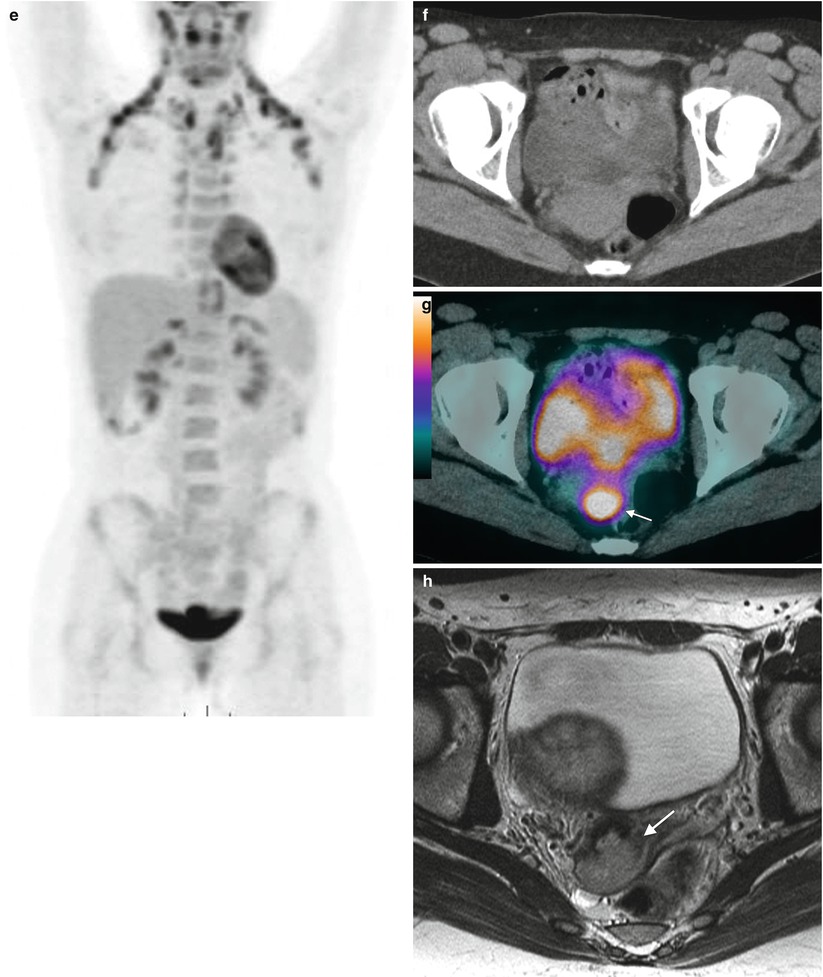

Fig. 6.10

High FDG uptake in primary adenocarcinoma of the cervix. This 23-year-old woman reported postcoital bleeding and metrorrhagia. A Pap smear was positive for human papillomavirus (HPV). MIP images (a, b) show increased FDG uptake just superior to the bladder (arrow) with a standardized uptake value (SUV) of 11.8. Sagittal CT, fused, and MRI images (c–e respectively) show focal uptake posterior to the bladder localizing to the cervical lesion. Fused axial CT and fused images (f, g) show localization of the activity in the cervix corresponding to the MRI images (h). Cervical biopsy revealed adenocarcinoma

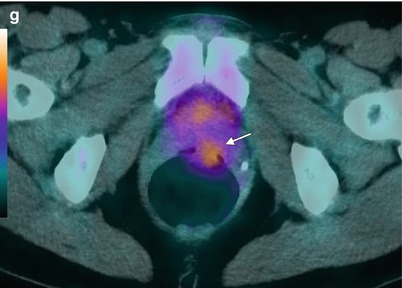

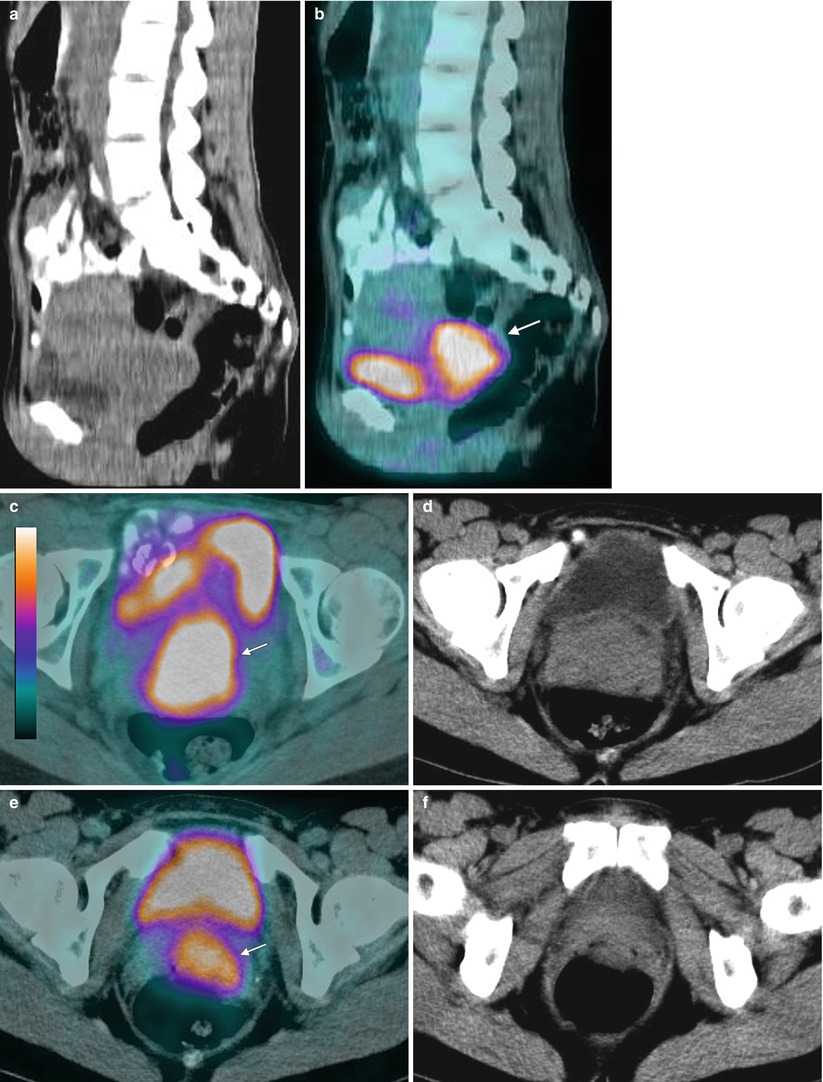

Fig. 6.11

High FDG uptake in primary squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix. This 45-year-old woman presented with abnormal bleeding. A Pap smear was positive for a high-grade lesion. Colposcopy was performed, and cervical biopsy revealed high-grade squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix. FDG PET was performed for staging. Intense uptake (SUV 9.2) was seen in the region of a cervical mass (arrow) seen on sagittal CT and fused PET/CT images (a, b) and axial image (c) that measured 4.9 × 4.4 × 3.7 cm, extending inferiorly up to the vaginal fornices seen on axial CT and fused PET/CT images (d–g). No FDG-avid nodal disease was seen

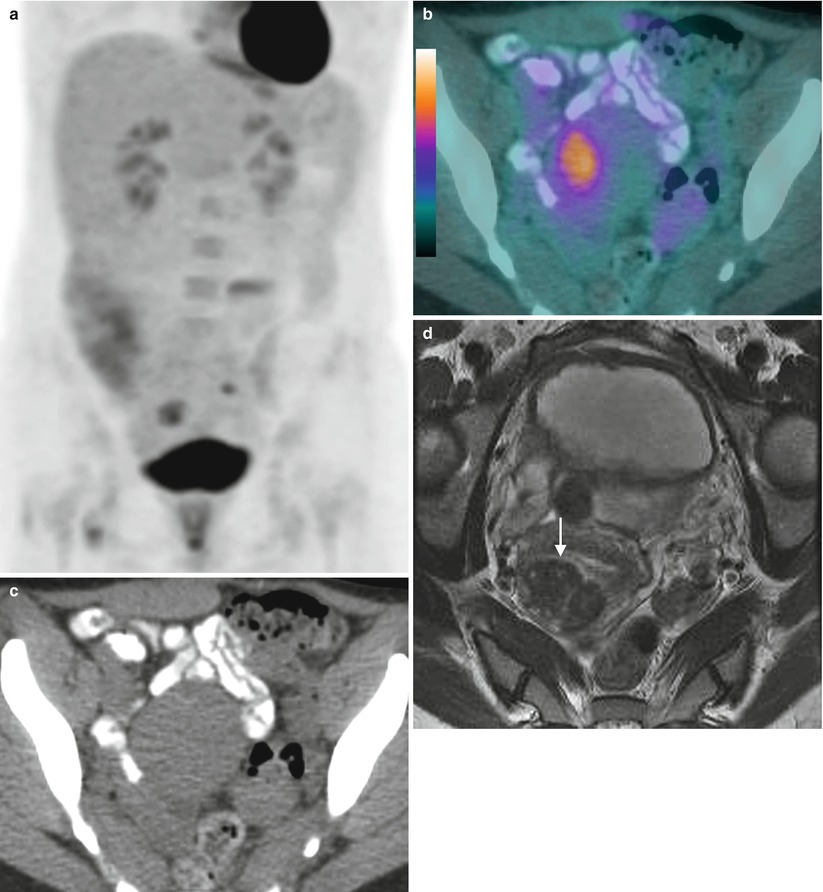

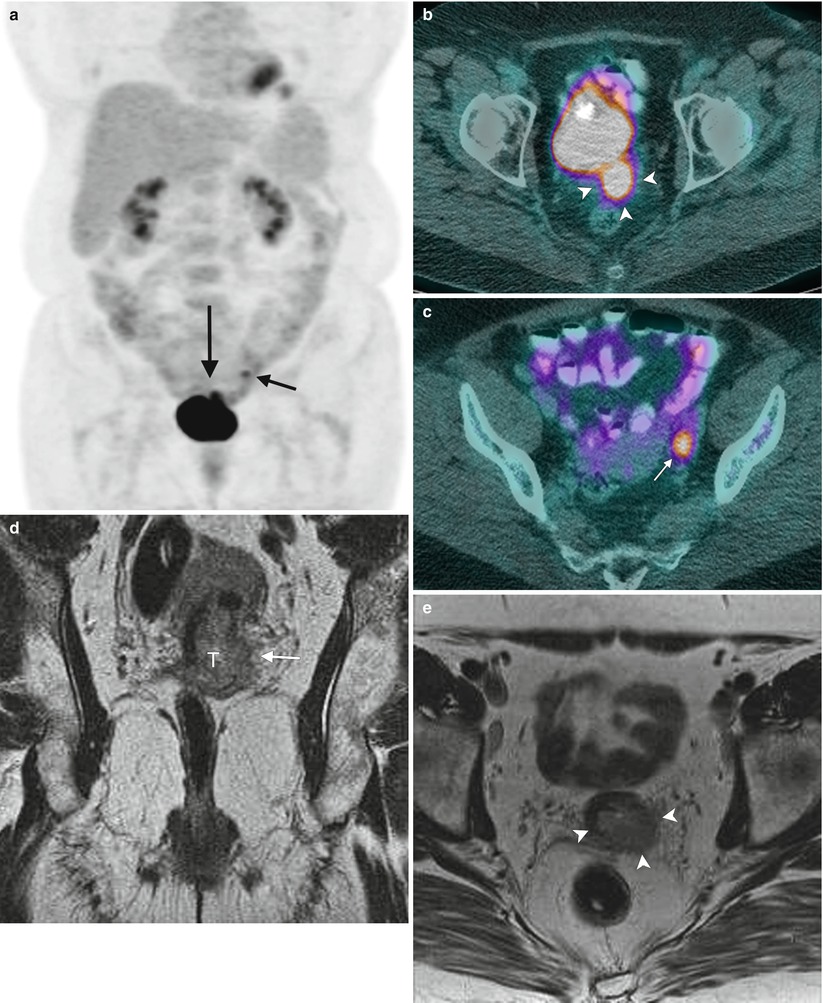

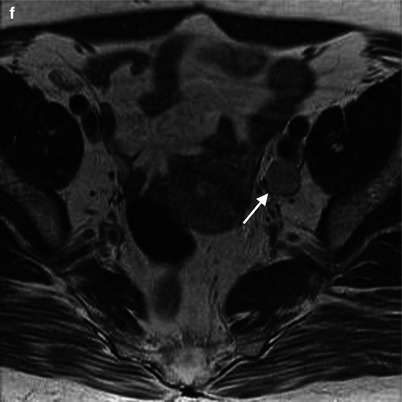

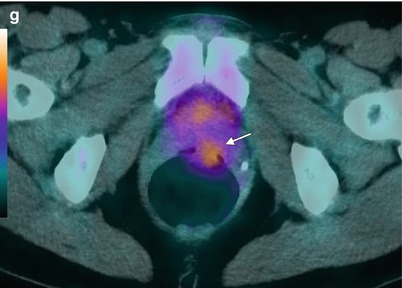

Fig. 6.12

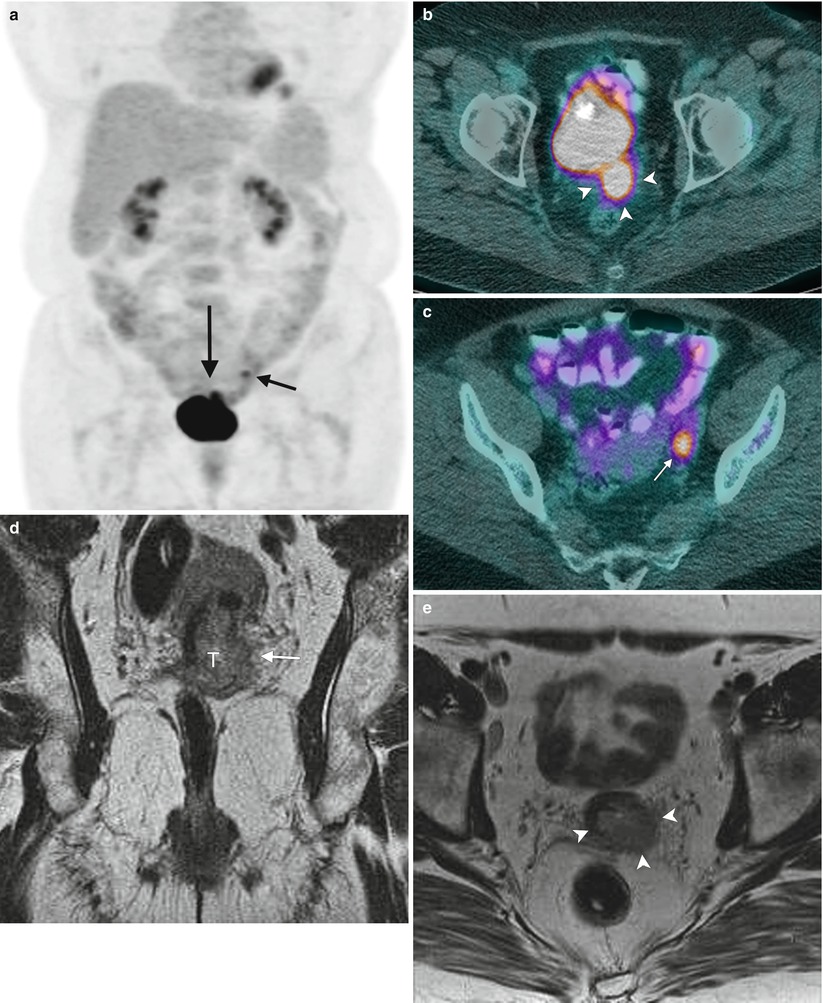

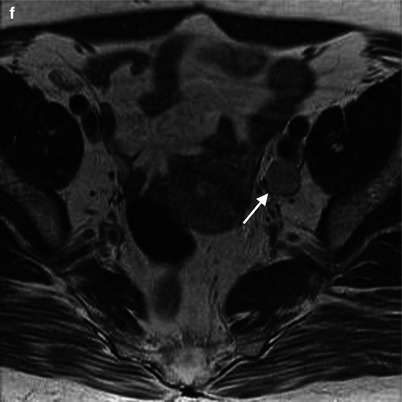

Increased FDG uptake in primary cervical cancer with parametrial involvement and nodal uptake. In a 55-year-old woman with cervical carcinoma, FDG PET was performed for staging. A MIP image (a) shows a small area of activity beyond the superior aspect of the bladder (long arrow), and fused images confirm uptake in the primary tumor (arrowheads) (b), corresponding to the lesion on MRI (c). FDG uptake is also seen in a lymph node (d) as also seen on MRI (e). No uptake was seen in the endometrium or ovaries (d). MRI also shows tumor (arrow) involving the parametrium (f). The patient underwent laparoscopic dissection. Pathology revealed poorly differentiated, high-grade adenosquamous carcinoma of the cervix and metastatic disease in the left external iliac node

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree