Ultrasound (US) imaging is prone to pitfalls related to technique, normal variations, and interpretative errors. Nowhere are these issues more problematic than in the female pelvis. In this anatomic region, numerous scanning approaches and transducers may be chosen. A range of findings may be normal or abnormal depending on the age of the patient, previous surgery, parity, medications, and the stage of the menstrual cycle. Lastly, one must consider pathologic processes with similar appearances and those in adjacent nongynecologic organs. In this chapter we will address a variety of recurrent pitfalls encountered over the years in our practice.

Scanning Technique and Related Pitfalls

Traditionally a patient presenting for pelvic sonography was requested to distend her urinary bladder. The distended bladder serves as a sonographic window for transabdominal imaging by enhancing the through-transmission of the sound beam and displacing gas-filled small bowel loops out of the pelvis to allow better visualization of the uterus and adnexae. Transvaginal imaging, which allows better resolution because of a higher frequency transducer, is best performed with an empty bladder. The competing requirements of transvaginal and transabdominal imaging, especially in patients without previous studies, often engender long waits, uncomfortable patients, frequent interruptions to empty a rapidly filling bladder, and a chaotic US schedule. As a result, several years ago we decided to forgo the requirement for a full bladder in most patients.

Our protocol begins with a brief transabdominal evaluation, surveying for a large uterus with exophytic fibroids, large adnexal masses or ovaries, and/or the uterus and ovaries displaced out of the pelvis. If none of these situations apply, we perform a transvaginal scan only. Occasionally transabdominal imaging alone is sufficient or even preferred, and sometimes a combination is required. The vast majority of our population can undergo a transvaginal examination. Children and teenagers are asked to distend their bladders and are scanned transabdominally.

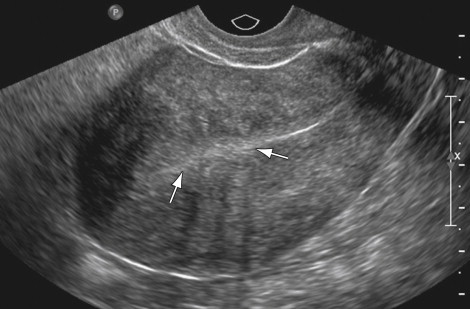

Our preference for transvaginal scanning may result in pitfalls for the less experienced sonographer or sonologist. In some cases, transvaginal scanning only images the cervix and lower uterine segment, missing the majority of the uterine body and fundus ( Figure 2-1 ). This situation occurs frequently in patients with a previous cesarean section when the lower anterior uterus is tethered to the anterior abdominal wall at the site of the cesarean incision. This scarring elongates the cervix, pulling the uterine body out of the pelvis and beyond the range of the vaginal transducer. A similar problem is encountered when only transvaginal imaging is performed in a patient with a large myomatous uterus. In these situations transabdominal imaging is preferred. To help in planning the scan, we inquire about a history of cesarean section in all parous patients.

We occasionally supplement or substitute with transperineal and transrectal imaging in women who cannot tolerate the lithotomy position or the vaginal transducer and in women who cannot maintain a full bladder. For transrectal imaging, the patient is placed in the left lateral decubitus position with flexed hips and knees. Generally this position and approach are well tolerated in the elderly population, allowing adequate visualization of the uterus and endometrium. Evaluation of the adnexal structures is often incomplete because the excursion of the transducer from side to side is more limited than on a routine transvaginal examination. Transperineal imaging is easily tolerated and helpful in evaluation of the vagina, cervix, and urethra.

Uterine Pitfalls

The Benign Enlarged Uterus

Fibroids occur in 20% to 30% of females more than 30 years old, accounting for many nongravid pelvic US referrals. Their diagnosis is usually straightforward. The most typical appearance is a hypoechoic solid mass with an internal whorled pattern, shadowing, and circumferential vessels. Rapid enlargement may lead to necrosis and degeneration and a variety of more atypical appearances with cystic or fatty components (lipoleiomyoma) and calcifications. Although most fibroids arise in the intramural portion of the uterus, less common locations may be subserosal, submucosal, cervical, and within the broad ligament. These variations in appearance and location may result in errors of diagnosis. A subserosal myoma with a thin attachment to the uterine body may be confused with a solid ovarian mass or even missed with transvaginal imaging. A myoma with significant cystic degeneration may simulate an ovarian cyst. Pressure with the transvaginal probe and/or color Doppler imaging to demonstrate bridging vessels between the uterine body and pedunculated myoma may help in the correct diagnosis. A densely calcified myoma is usually not a diagnostic dilemma, but the shadowing may cause significant technical limitations in evaluation of the adnexa and the endometrium.

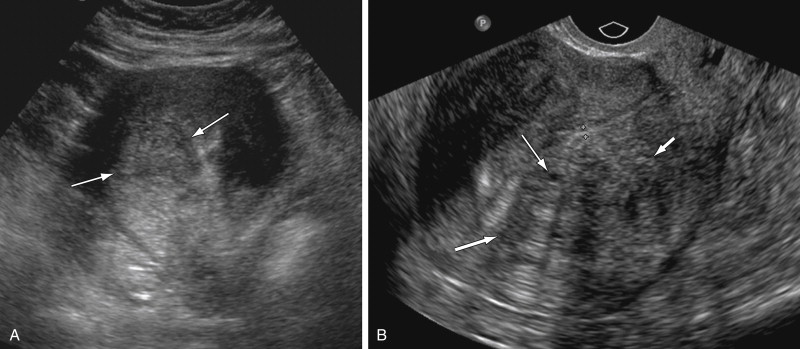

Usually multiple fibroids result in the classic US appearance of an enlarged, lobulated uterus with hypoechoic masses and variable amounts of posterior acoustic shadowing. Even when the posterior shadowing is dense, the anterior lobulated margin allows one to make the correct diagnosis. Somewhat confusing, however, is the patient with an enlarged uterus secondary to a large dominant fibroid. Frequently the large fibroid is mistaken for the entire uterus when this dominant fibroid displaces a smaller, more normal-appearing uterine corpus toward the periphery ( Figure 2-2 ). Distinguishing between a solitary enlarged myoma and multiple myomata may affect treatment options. One should be wary of this pitfall when presented with images of a uterus that appears as a single mass without any normal myometrium. A careful search for the endometrium and its connection to the endocervical canal using transabdominal and transvaginal techniques may help to avoid this error.

Diffuse or focal enlargement of the uterus may also be caused by adenomyosis. In adenomyosis the extension of endometrial glands into the myometrium causes smooth muscle hypertrophy accounting for enlargement of the uterus. Sonographic features include heterogeneity of the myometrium with cysts and hyperechoic foci, linear striations, thin non-edge shadows, penetrating vessels, and poor definition of the endometrial myometrial junction. The contour of the uterus is usually more globular and less lobulated than with multiple fibroids ( Figure 2-3 ).

Distinguishing between focal fibroids and focal adenomyosis (adenomyoma) is more challenging and prone to potential errors ( Figure 2-4 ). Findings that favor an adenomyoma over a myoma include poorly defined margins, minimal mass effect on the adjacent endometrium, small cysts, ellipsoid versus spherical shape, presence of echogenic foci and striations, and the absence of calcifications, edge shadowing, and large vessels at the margin of the lesion. With the improvement of US equipment in the past 10 to 15 years, we have seen several cases initially interpreted as fibroids that on subsequent studies are focal regions of adenomyosis. Because patients with fibroids and adenomyosis have similar symptoms, differentiation between the two diagnoses is important because treatment options differ. Finally, in cases with adenomyosis and fibroids, shadowing from the fibroids may limit evaluation of the presence and severity of the adenomyosis.

An enlarged uterus may be palpated in patients with duplication anomalies such as a bicornuate or didelphys uterus because of the separation of the two uterine horns. When the endometrial canal is divided, the uterine fundus must be evaluated to differentiate a septate uterus from a bicornuate or didelphys uterus. Pregnancy outcomes and treatment options vary significantly for these different anomalies. Volumetric US imaging is helpful in differentiating these entities. Reconstruction of the true coronal plane of the uterus allows evaluation of the peripheral fundal contour and the extent of separation of the endometrial canals. A superior exophytic fibroid arising in an otherwise normal uterus may be confused for a bicornuate uterus because they have similar contours. The lack of a split endometrial canal and classic findings of a fibroid should help distinguish these two diagnoses.

False-Positive Diagnosis of Fibroids

Fibroids may calcify, but not all uterine myometrial calcifications are fibroids. Calcification of arcuate uterine arteries is common in elderly women, especially those with diabetes, and is considered part of the normal aging process. Arcuate artery calcifications usually appear as discontinuous linear parallel echoes ( Figure 2-5 ) located between the outer and intermediate layers of the uterine myometrium. These calcifications must not be confused with calcification in uterine fibroids, which tend to be coarser and clumped and often associated with a noncalcified mass. Intense shadows from arcuate vessel calcification may obscure the endometrium and make it difficult to distinguish from the leading edge of a calcified myoma. Magnetic resonance may be the only imaging method for evaluation of the endometrium in this situation.

A frequent site for an erroneous fibroid diagnosis is the lower uterine segment in a patient with a history of previous cesarean section. The cesarean section incision is usually transversely oriented in the lower uterine segment where there is increased fibrous tissue available for healing, thereby reducing the chance of future dehiscence. Not infrequently, distortion and prominence of the overhanging tissue superior to the scar ( Figure 2-6 ) assumes a rounded, relatively hypoechoic appearance, mistaken for a fibroid ( Figure 2-7 ). Thurmond et al. suggest that differences in muscle contraction may account for the thicker superior edge of the scar that becomes more pronounced with increasing numbers of cesarean sections. Histologic evaluation reveals congestion of the endometrium above the scar, which may also account for this prominent tissue.

The presence of posterior edge shadowing adds to the similarity of this scar tissue to a focal fibroid. This artifact manifests as narrow, vertical hypoechoic lines originating along the lateral margin of a rounded structure. Edge artifact is common along the border of a cesarean section scar because of the rounded configuration of the myometrium adjacent to the scar. The hypoechoic edge artifact may be mistaken for posterior acoustic shadowing, further confusing this configuration for a fibroid ( Figure 2-7 , B ).

Endometrium

The endometrial thickness and appearance must be correlated with the menstrual status to assess for benign or malignant causes of bleeding such as polyps, fibroids, hyperplasia, and cancer. Accurate identification of the endometrium may be challenging in patients with multiple fibroids. Anterior fibroids that significantly attenuate the sound beam may completely obscure the endometrium. In addition, one must avoid mistaking tissue heterogeneity within fibroids or tissue interfaces between fibroids as the endometrium ( Figure 2-8 ).

The endometrium is measured in the midline sagittal plane of the uterus. If the uterus is oriented obliquely or coronally, a true sagittal plane may be impossible to obtain with routine imaging. Oblique images of the endometrium may falsely increase its measurement and result in overdiagnosis of endometrial thickening. Frequently this problem is worse on transvaginal imaging and may be overcome on transabdominal images, which allow for more scanning planes. Three-dimensional volume acquisition can correct for uterine obliquity by allowing visualization of the endometrium in a multitude of reconstructed planes regardless of the original acquisition plane.

Faulty measurement of the endometrium may occur in patients with adenomyosis, especially with transvaginal imaging. The increased resolution of the transvaginal transducer allows for improved visualization of the ectopic endometrial tissue located in the myometrium. The striations or patches of ectopic tissue cause poor definition of the endometrial myometrial junction ( Figure 2-9 ) and may cause pseudowidening of the endometrium ( Figure 2-10 ).