Radiologists are often asked to evaluate the postoperative colon to exclude complications such as fistula, dehiscence, stricture, and abscess formation. Radiologists are also called on to assess the colon in the asymptomatic patient for anastomotic healing or resolution of inflammatory disease before a colostomy is closed. The radiologist must be familiar with the details of the surgical procedure, terminology, and individual surgeon’s modifications to render an intelligent consultation. The major surgical procedures performed on the colon are discussed in this chapter. Although there is increasing use of the laparoscopic approach to colonic surgeries, the structural end results are similar to those of their open counterparts. The minute intraoperative technical details have been well described in classic surgical textbooks.

Segmental Resection

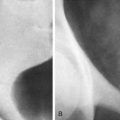

Segmental resection entails surgical removal of a diseased segment of the colon. Colonic continuity is usually restored with an end-to-end colocolic or ileocolic anastomosis ( Figs. 63-1 and 63-2 ). The latter is created for patients who undergo resection of the cecum or right colon. In some patients, the anastomotic line may be seen as a short-segment, ringlike indentation during contrast examination of the colon ( Fig. 63-3 ), but in many patients the site of the anastomosis may not be discernible unless defined by surgical staples. Currently, most surgeons use stapling devices rather than traditional hand-sewn anastomoses to reestablish bowel continuity. The stapling units usually create a uniform ring of staples. Disruption of the ring on a plain film of the abdomen may indicate disruption of the anastomosis. A segmental resection may be performed in conjunction with an upstream diverting ileostomy or colostomy (see later).

Prior to colostomy takedown, the surgeon may request a preoperative examination of the anastomosis to ensure integrity. In terms of technique, the examination is performed after placement of a rectal tube or Foley catheter into the rectum, with instillation of water-soluble contrast material under fluoroscopy. The examination should focus on the region of the anastomosis, with imaging performed in multiple projections and with the patient in a variety of positions. In particular, the examination should be performed with a mild degree of stress to the anastomosis. For example, rather than performing an examination of a sigmoid anastomosis entirely in the recumbent position, a high-pressure view of the sigmoid in a right posterior oblique and/or reverse Trendelenburg position should be performed. This will create a column of contrast at the level of the anastomosis, potentially revealing a leak that could be missed if the contrast flowed past the anastomosis in a low-pressure position (left posterior oblique and Trendelenburg position).

Side-to-Side Enterocolic Anastomosis

A side-to-side enterocolic anastomosis ( Fig. 63-4 ) may be created when a diseased segment of distal small bowel (as in Crohn’s disease or radiation enteritis) is bypassed or when the length of the functional small bowel is shortened for treatment of morbid obesity. Currently, this procedure is rarely performed in isolation. Surgeons prefer to resect rather than bypass small bowel involved by Crohn’s disease. Gastric restrictive surgeries, including gastric stapling and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, are much preferred over a small bowel bypass procedure as therapy for morbid obesity (see Chapter 35 ).

Colostomy

A colostomy is a colocutaneous opening, or stoma, created to decompress a colonic obstruction or divert the fecal stream away from the distal colon. Diverting colostomies may be performed to protect a distal anastomosis that has recently been created and requires time to heal or to direct the fecal stream away from a segment of distal colon that is too inflamed to be resected at the time of the initial operation. If the surgeon elects to resect the diseased segment, he or she may choose to perform an end-to-end anastomosis and divert the fecal stream with a temporary colostomy. The colon proximal to the stoma is often evaluated radiographically to rule out additional colonic lesions, whereas the distal colon is evaluated to assess the status of a distal anastomosis or a previously inflamed segment.

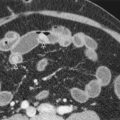

Stomal creation is associated with a number of complications. Necrosis may occur if the blood supply is compromised by tension or compression during formation of the stoma. The stoma may become detached from the abdominal wall and migrate into the abdominal cavity. With stomal recession, it may remain attached to the abdominal wall but retract into the abdomen, causing inflammation of the surrounding skin. The bowel may also prolapse or intussuscept through the stoma. When they occur, parastomal hernias may contain small or, rarely, large bowel that passes through an enlarged fascial defect adjacent to the stoma. The hernia may remain in the subcutaneous tissues ( Fig. 63-5 ) or may protrude externally beside the stoma. In obese patients, these hernias can be difficult to detect clinically but are readily apparent on abdominal computed tomography (CT) scans. Parastomal hernias can result in bowel obstructions and can be difficult for the surgeon to repair. Parastomal hernias causing stomal obstruction or dysfunction may be intermittent. When examining a stoma at fluoroscopy, tangential views should be obtained with and without a Valsalva maneuver to elicit bowel herniation into a parastomal hernia. Stomal ulceration may occur because of mechanical irritation from the stomal appliance. The choice of colostomy depends on whether it is to be permanent or temporary, the patient’s body habitus, previous operations, and the surgeon’s preference.

End-Colostomy

An end-colostomy may be performed as a definitive procedure in patients with distal rectal carcinoma or as part of a two-stage procedure for diverticulitis. The stoma is usually in the left lower quadrant, and the descending colon or residual sigmoid colon is the portion that forms the stomal opening. This procedure is often performed in association with the Hartmann procedure to close off the rectal stump, so only one stoma is present.

Loop Colostomy

A loop colostomy is usually performed for the following indications: (1) as a temporary procedure to relieve an acute obstruction of the distal colon or to protect a new distal colonic anastomosis; and (2) as a permanent procedure for unresectable advanced lesions. A loop of transverse or sigmoid colon is brought to the surface of the abdominal wall, sutured in place on the outside, and then opened up, creating afferent and efferent stomas. The mucosa connecting the two stomal openings is the posterior wall of the colon. Patients are usually aware of which stoma produces feces and are able to direct the radiologist to examine the correct portion of the colon.

Double-Barreled Colostomy

A double-barreled colostomy is created when the colon is divided completely and the two cut ends are sewn side by side to each other, but this type of colostomy is rarely performed. This type of stoma also has two openings, and the patient can usually tell which one is the productive orifice. This procedure is chosen because the stoma can be closed without reentering the abdomen. The apposed common walls are cut, and the stoma closes spontaneously, or the margins of the two stomal openings can be pursed together with minimal suturing under local anesthesia.

Divided Colostomy and Mucous Fistula

A divided colostomy and mucous fistula operation creates two separate colostomies—one for the proximal colon, creating an efferent or productive stoma, and one for the distal colon, creating an afferent stoma ( Fig. 63-6 ). From the afferent stoma, the colon carries only mucus to the rectum; this stoma has been called a mucous stoma or mucous fistula. This procedure is not commonly performed but may be chosen to ensure that no fecal debris enters the distal colon.

At 6 to 8 weeks, the colon is usually reexamined before closing the diverting colostomy to ensure that there is no leakage and that regional inflammatory changes have subsided. When the colon is evaluated to exclude a fistula, a single-contrast rather than a double-contrast barium enema study should be performed. Barium is safe to use in the asymptomatic patient because extravasation, when it occurs, has a well-formed sinus tract, and barium does not enter the peritoneal cavity. Also, barium has contrast characteristics superior to those of water-soluble contrast agents, which may not be sufficiently dense and can become diluted in such a tract, making it difficult to visualize tiny tracts during fluoroscopy of organs low in the bony pelvis.

After diversion of the fecal stream with a colostomy, the distal colon may have an abnormal appearance when examined before closure. The unused segment of the colon may appear nondistensible and may have an abnormal mucosal pattern, with nodularity and lymphoid follicular hyperplasia. This condition is known as diversion colitis. The apparent absence of distensibility is probably the result of chronic lack of distention, and the mucosal irregularity is likely secondary to adherent mucus in a contracted and unprepared colon. Patients may be asymptomatic; this entity likely represents a radiographic phenomenon rather than a true colitis. With restoration of the fecal stream after closure of the colostomy, the morphologic features of the colon return to normal unless underlying colonic inflammatory disease is present. A deformity may be created at the site of the previous colostomy and may cause radiographic confusion when the history is not correlated with the radiographic examination. The appearance is variable and may resemble that of a polypoid filling defect, smooth or nodular annular lesion, or submucosal or serosal process (see Fig. 63-3 ). Any colonic operative or endoscopic procedure may also produce a persistent deformity that can mimic disease ( Fig. 63-7 ). Careful review of the patient’s history should prevent a misdiagnosis.

Cecostomy

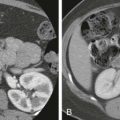

Cecostomy is a surgical procedure in which an opening is created in the cecum to relieve cecal distention produced by intestinal pseudo-obstruction, profound paralytic ileus, or, rarely, distal obstruction (e.g., tumor, cecal volvulus). It is a temporizing or palliative measure in acutely ill patients and in those who would not tolerate a definitive but more prolonged right hemicolectomy and ileal ascending colonic anastomosis ( Fig. 63-8 ) or resection of a distal colonic obstructive process. A tube is placed in the cecum and brought to the abdominal surface to relieve colonic distention. A cecostomy may be performed by the surgeon, interventional radiologist, or gastroenterologist. A definitive surgical procedure can later be performed when the patient’s condition permits.