Chapter Outline

Small Bowel After Gastric Surgery

Surgical treatment of disease of the small bowel requires the use of relatively few operative techniques, and most of these surgical interventions are applicable to any segment of the jejunum and ileum. Primarily, they include enterotomy for removal of polyps or foreign bodies, enteroplasty for treatment of strictures, enterectomy for resection of obstructed, traumatized, neoplastic, or necrotic segments, plication to prevent intestinal obstruction, and creation of ostomies or mucous fistulas for feeding or drainage purposes. In addition, the small bowel is used for the surgical construction of reservoirs after gastrectomy and proctocolectomy and for the reconstitution of biliary and pancreatic flow into the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Another development is the surgical option of small bowel transplantation for the treatment of select patients with short bowel syndrome and intestinal failure.

Radiologic studies are seldom performed as routine follow-up of the surgical procedure, but are done to assess the integrity of the small bowel or investigate postoperative complications. Appreciation of postoperative anatomy and associated intestinal alterations can be especially important because the pertinent surgical history may be incomplete or even unknown at the time of diagnostic imaging. In patients with a history of small bowel surgery who present with GI symptoms, the postoperative anatomy and site of any anastomosis can be evaluated by small bowel enteroclysis techniques. However, experience with CT enteroclysis is limited to a few institutions. An alternative technique for achieving adequate bowel distention is CT enterography, which does not require intubation but the patient must drink large quantities of oral contrast in a short period of time. Considering many factors specific to the patient and institution, the radiologist would make a choice between the intubation-infusion method (enteroclysis) and the oral approach (enterography).

Small Bowel After Gastric Surgery

Important although uncommon alterations in small intestinal physiology or anatomy may occur after certain operations on the stomach. In the postgastrectomy syndrome, various pathophysiologic disorders result from interruption of the pyloric sphincter mechanism or from the sequelae of a vagotomy. Rapid influx of hyperosmotic gastric contents into the small bowel may manifest clinically as the dumping syndrome, with symptoms of postprandial cramping and urgent diarrhea. Mild luminal dilation and hypermotility of the efferent jejunum can be observed on small bowel studies. Serotonin, enteroglucagon, and vasoactive intestinal polypeptide are also released systemically by the small intestine in response to luminal distention and are partly responsible for the vasomotor component of dumping. Small bowel dysmotility with bacterial colonization, intestinal malabsorption, and impaired pancreatic and biliary function may also contribute to postvagotomy diarrhea.

Afferent Loop Obstruction

An afferent loop may be created with an esophagoenterostomy, gastroenterostomy, or enteroenterostomy that results from various gastric or pancreaticogastric operations. In Billroth II gastrojejunostomy, the afferent loop is the duodenum, in Whipple’s procedure it is the Roux jejunal limb, and in Roux-en-Y gastric bypass the afferent loop is the duodenum and proximal jejunum. Afferent loop obstruction, also referred to as biliopancreatic limb obstruction, is an uncommon complication of these surgical procedures and occurs with variable clinical severity, acuteness, and chronicity. Afferent loop syndrome refers to chronic partial obstruction of an afferent loop. Causes include stenosis of the anastomosis, adhesions, retrograde intussusception, volvulus, internal hernia, recurrent neoplasm, and inflammatory disease. The clinical diagnosis of afferent loop obstruction can be difficult because patients may have vague symptoms or the classic finding of bilious vomiting with relief of abdominal pain. Acute obstruction can result in pancreatitis, whereas chronic progression of the syndrome can result in malabsorption, intestinal bleeding, or perforation.

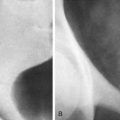

Abdominal radiographs are often normal because the obstructed afferent loop is fluid-filled because of ongoing accumulation of biliary, pancreatic, and intestinal secretions. GI barium studies may suggest the diagnosis if there is nonfilling of the afferent loop or preferential filling of a dilated afferent loop associated with stasis ( Fig. 48-1 ). However, the efficacy of barium studies is questionable because the afferent loop fails to opacify in 20% of normal patients.

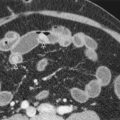

Computed tomography (CT) is helpful in visualization of the obstructed afferent loop. A characteristic finding on the CT is a dilated, U-shaped afferent loop that traverses the midline ( Fig. 48-2 ). Nonopacification of the afferent loop is usual after oral contrast administration. Transmitted pressure from the obstruction may be sufficient to distend the gallbladder and bile ducts. Coronal CT images aid in identifying the course of the obstructed loop and differentiating the intestine from other fluid collections ( Fig. 48-3 ).

Enterectomy and Anastomosis

Enterectomy refers to surgical excision of the intestine and its corresponding mesentery, as indicated by a wide variety of clinical conditions. Primary anastomosis generally follows segmental resection of the small bowel, although in some patients an external ostomy is created in conjunction with closure or formation of a mucous fistula of the distal bowel segment.

Anastomosis of the small bowel is one of the most commonly performed GI surgical procedures because it is required for reconstituting continuity of the intestine after resection, bypassing an obstructed intestinal segment, and forming an enteric reservoir. Mechanical sutures and staples are established forms of instrumentation equal to the use of manual suturing techniques for all types of intestinal operations.

Intestinal anastomoses can be constructed as an end-to-end, functional end-to-end (anatomic side-to-side), end-to-side, or side-to-side anastomosis ( Fig. 48-4 ). An end-to-end anastomosis is preferred to reestablish continuity of the small bowel, provided there is minimal disparity in luminal size. An end-to-end anastomosis ideally serves to avoid small bowel stasis syndromes. Closing the two ends of an excised bowel segment and performing a side-to-side anastomosis in close proximity to the closed ends creates a functional end-to-end anastomosis that provides an increased anastomotic surface. An end-to-side anastomosis is used to compensate for disproportionate proximal and distal luminal sizes, and a side-to-side anastomosis is indicated in unusual clinical situations that require expeditious bypass of an intestinal obstruction (e.g., as with extensive neoplastic disease of the small bowel). When an end-to-side anastomosis is performed, the end of the proximal lumen is anastomosed to the side of the distal intestinal segment. This arrangement ensures that peristalsis within the blind (distal) segment is directed antegrade toward and beyond the anastomotic opening, thereby preventing stasis ( Fig. 48-5 ).

Despite careful preoperative patient preparation and meticulous surgical technique, dehiscence of small bowel anastomoses can occur. Aside from technical considerations, several factors may adversely affect the success of an anastomosis, including sepsis, tissue hypoxia, malignancy, and advanced patient age. Intestinal perforation from an anastomotic dehiscence may be detected by the presence of free intraperitoneal air on abdominal radiographs. Contrast studies performed with water-soluble contrast media may demonstrate an intestinal leak, although similar findings are detectable on CT, which also provides the advantage of localizing contaminated peritoneal fluid and imaging the complication of abscess formation. Extraintestinal fluid collections, which progressively increase in volume in the postoperative period, are suggestive of an anastomotic disruption, and evidence of enteric contrast media extravasation is diagnostic. Suture dehiscence with a small or contained intestinal leak can also result in a localized perianastomotic inflammatory process or phlegmon, which may result in partial intestinal obstruction ( Fig. 48-6 ).

Postoperative Blind Pouch and Loop

Although the anatomic end-to-end and functional end-to-end surgical anastomoses have essentially replaced the side-to-side anastomosis to restore bowel continuity, the latter procedure is occasionally performed, and a postoperative blind pouch may develop. It should be appreciated that a blind pouch is not intentionally created, unlike a postoperative blind loop. During side-to-side anastomosis, division of the circular muscle can result in local dysmotility with stasis that leads to progressive dilation of the proximal anastomotic segment and formation of a blind intestinal pouch. An incorrectly performed end-to-side anastomosis (side of the proximal segment of intestine sutured to the end of the distal intestine) creates a similar anatomic abnormality. Occasionally, blind pouches may be encountered in association with a prior functional end-to-end (anatomic side-to-side) surgical anastomosis because of abnormal local peristalsis and stasis.

In addition to intestinal stasis with potential for bacterial overgrowth, a postoperative blind pouch can be associated with inflammation, ulceration, and intestinal bleeding. Symptoms of abdominal pain and distention, episodic diarrhea, and a history of previous intestinal anastomosis suggest the clinical syndrome and its underlying abnormality, but diagnostic confirmation requires radiologic imaging. Segmental pouch resection and a restorative end-to-end anastomosis are corrective and eliminate the associated complications.

On CT, an intestinal blind pouch is recognized as a distinct saccular enteric structure, with surgical clips visible in the adjacent region. Small bowel contrast studies, particularly enteroclysis and CT enteroclysis, demonstrate the pouch and its anastomotic relationships ( Fig. 48-7 ).

Although some clinical features are in common with the blind pouch syndrome, the anatomic abnormality associated with the blind loop syndrome is different. In blind loop syndrome, a segment of small intestine has been completely bypassed from the enteric stream by an enteroanastomosis. Stagnation of small bowel contents within the blind loop leads to bacterial overgrowth, which, in the most severely affected patients, can approximate the composition of normal colonic flora in quantity and complexity of organisms. Bacterial overgrowth in the small intestine may result in profound disturbances of absorptive function, with malabsorption of lipids and vitamin B 12 being most notable. Symptoms and clinical signs of the syndrome are those of malabsorption and include diarrhea, steatorrhea, anemia, and nutritional deficiencies. As in the diagnosis of blind pouch, dedicated small bowel enteroclysis studies can accurately demonstrate the postoperative anatomic abnormality.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree