Omid Kohannim • Justin McWilliams

BACKGROUND

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

Postpartum hemorrhage (PPH), defined as blood loss exceeding 500 mL after vaginal delivery or 1,000 mL after a cesarean section, has an incidence of 5% to 8% and is among the leading causes of maternal mortality across the world. Approximately 140,000 women die from the condition every year. Mortality from PPH has decreased in Western countries; nonetheless, it remains one of the top causes of death from pregnancy in the United States, United Kingdom, and France. In addition to causing mortality, PPH also leads to morbidities, such as coagulopathy, shock, renal failure, and acute respiratory distress syndrome.1–3

The most consistent risk factors for PPH are fetal macrosomia, retained placenta or prolonged third stage of labor, prolonged labor in general, delivery via cesarean section, trauma to the genital tract, and the avoidance of uterotonic agents in the third stage of labor.1 Several other risk factors, such as placenta accreta, instrumental delivery, and hypertensive disorders have also been reported.4 Demographic factors, such as Hispanic and non-Hispanic white ethnicity have also been found to increase risk for PPH.5 Unfortunately, however, PPH remains relatively unpredictable from a clinical standpoint.

Etiology and Diagnosis

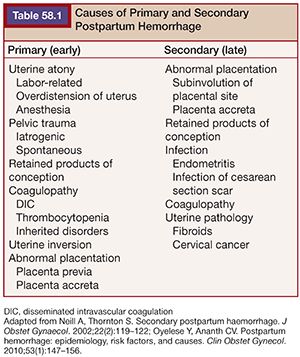

Etiologies of PPH can be divided into six categories: uterine atony, trauma to the genital tract, retained products of conception, coagulopathy, uterine inversion, and abnormal placentation. Uterine atony accounts for most causes, as normal uterine contraction and subsequent compression of large vessels between muscle fibers are the prime mechanisms of preventing hemorrhage. Each of the previously mentioned etiologies can be further subcategorized. Uterine atony, for instance, can be related to labor (e.g., induction, prolonged labor, infection), uterine overdistension, or anesthetics. Similarly, coagulopathy can be subdivided into disseminated intravascular coagulation, thrombocytopenia, anticoagulation, and inherited disorders.1

There are two categories of PPH: early or primary PPH refers to excessive bleeding that occurs within 24 hours after delivery, whereas late or secondary PPH occurs between 24 hours and 6 to 12 weeks after delivery.6,7 Primary and secondary PPH have incidence rates of 4% to 6% and 1%, respectively. Causes of primary and secondary PPH vary. Primary PPH is usually due to the so-called four Ts, which refer to tone (i.e., lack thereof, or atony), trauma, tissue (i.e., retained products of conception), and thrombosis. These account for approximately 70% to 80%, 28%, 11%, and 1% of causes, respectively. Secondary PPH is usually caused by retained products of conception, subinvolution of placental site, infection, and coagulopathy.2,8,9 Etiologies of primary and secondary PPH are summarized in Table 58.1.

As mentioned earlier, most cases of PPH are due to uterine atony, which is often a clinical diagnosis. There are occasions, however, when clinical diagnosis is difficult, and imaging may become helpful. Although ultrasonography is the first-line imaging modality in patients with PPH due to its safety and low cost, it may be limited by pain and bowel gas and cannot typically pinpoint the source of acute hemorrhage. Computed tomography (CT) imaging may be more useful in certain cases. In PPH, CT may identify severe arterial bleeding in the arterial phase, and smaller hemorrhage in the delayed phase, by visualization of contrast extravasation into the uterine cavity. This cannot only be diagnostically valuable when clinical evidence is unreliable but also guide subsequent interventions by pinpointing the site of bleeding. CT can also delineate other causes of PPH, such as concealed or puerperal genital hematomas.2 In particular, if a patient has signs of PPH without direct vaginal bleeding, CT is indicated7. Uterine rupture, which has a hypoattenuating appearance within the highly enhancing myometrium, may also be diagnosed with CT. When retained products of conception are suspected as the etiology of PPH, an echogenic, intracavitary, endometrial mass on ultrasonography or T2-hyperintense lesions on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can also be used for diagnosis.2

Management

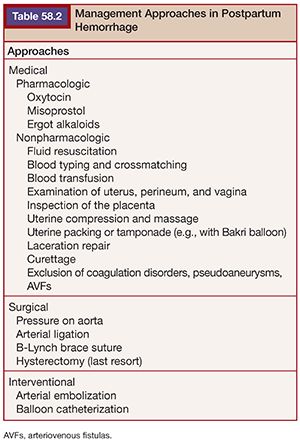

The management of PPH requires a multidisciplinary approach, often involving the obstetricians, nurses, anesthesiologists, laboratory specialists, and radiologists. Management always begins with resuscitative and conservative measures, necessitating close attention to airway, breathing, and circulation. Close monitoring, large-bore intravenous lines, blood cross-typing, and transfusion are often needed. Pharmacologic treatment predominantly entails the use of uterotonic agents to control bleeding and is typically the next step in management. Uterotonic agents include oxytocin, prostaglandins, and ergot derivatives such as methylergonovine. Administration of uterotonic agents addresses the most common cause of primary PPH, which is uterine atony. Minor procedures such as repair of lacerations, uterine compression, massage, and tamponade are also important components of the management, particularly when uterotonic agents do not suffice. One particular tamponade technique involves the use of a Bakri balloon (Cook Medical, Bloomington, Indiana),9 which has been shown to be effective in several case studies.10,11 This is a 24-Fr, 58-cm silicone device with two drainage holes at the tip of its shaft and a balloon, which can be inflated up to 800 mL, although usually no more than 500 mL. Bleeding control may be achieved by inserting this device through the cervical opening and pulling it from the vagina during cesarean section or inserting it through the vagina during a vaginal delivery, both of which are then followed by vaginal packing, balloon inflation, and drainage.9 In addition to these procedural measures, the uterus should be closely inspected for any retained products or clots.

When medical and conservative measures fail, PPH may then be surgically managed with arterial ligation and placement of a brace suture. Hysterectomy is typically the last resort. The management steps partly depend on the mode of delivery. If the patient is bleeding after cesarean section, surgical management may be more plausible. Alternative causes for bleeding should also be explored in refractory cases. In patients with coagulopathy, for instance, plasma components need to be replaced. As we will discuss later, it has become increasingly apparent that interventional radiology can play an important role in the management of PPH through arterial embolization and balloon catheterization, ideally replacing the need for surgery. Various approaches in the management of PPH are listed in Table 58.2.3,6

TECHNICAL DETAILS

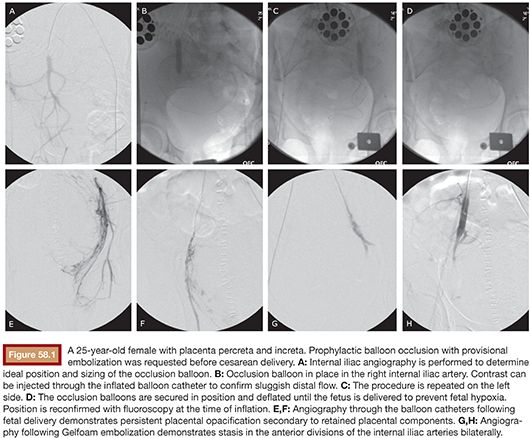

In 1979, Brown et al.12 introduced angiographic arterial embolization as an alternative technique to control PPH, offering advantages over surgery, including specific identification of bleeding sites and potential preservation of fertility. In their paper, Brown et al.12 described the case of a 22-year-old woman with preeclampsia who underwent labor augmentation and subsequently developed primary PPH refractory to conservative management. When her bleeding continued despite evacuation of a large posterior hematoma and total hysterectomy, she was transferred to a radiology suite, where angiography revealed bleeding from an internal pudendal artery branch. Embolization with Gelfoam (Pharmacia & Upjohn, Kalamazoo, Michigan) was performed, which led to control of bleeding and stabilization of the patient (Fig. 58.1). Soon after, Pais et al.13 reported two cases of arterial embolization for achieving hemostasis in PPH. Since the Brown et al.12 and Pais et al.13 cases, arterial embolization has been extensively studied for PPH and its value has been increasingly recognized despite the fact that several questions still remain unanswered in the field.14

Anatomy

The uterine artery, which is the predominant supply to the uterus, originates from the anterior division of the internal iliac (hypogastric) artery. This artery divides into a large ascending branch and a small descending branch. The descending branch is also called the cervicovaginal artery and supplies the cervix and vagina. The ascending branch gives off multiple arcuate vessels to the body and fundus of the uterus then divides into the tubal and ovarian terminal branches. The vaginal artery can either originate from the anterior division of the internal iliac artery or arise from the uterine artery. The ovarian artery, which supplies about 10% of the uterine fundus, originates from the aorta and makes anastomoses with uterine artery branches.2,12 Knowledge of pelvic arterial anatomy, in addition to the anatomical variations in the anterior division of the internal iliac artery,15 can help improve treatment success and safety of arterial embolization in PPH.

Technique

The technique of arterial embolization in the setting of PPH has not greatly changed since the first reported case by Brown et al.12 After local anesthesia, arterial access is achieved with a catheter through the common femoral artery, typically unilaterally, although a bilateral approach has also been espoused due to its rapidity.16 Diagnostic angiography of the internal iliac arteries, particularly of the anterior division, is performed to study the anatomy and detect extravasation. Embolization of both uterine arteries under fluoroscopic guidance is typically attempted next, most often empirically. Unilateral embolization is not usually done as recanalization of collateral vessels may lead to more bleeding. Internal iliac and abdominal angiography may also be performed as the source of bleeding may not be the uterine artery.3,7,17 The anterior division of the internal iliac arteries may be embolized when access to the uterine arteries or identification of the exact source of hemorrhage is difficult.3 Postembolization angiography is conducted to ensure extravasation has stopped. In cases of recurrent PPH, there may be other sources of bleeding such as the ovarian artery, which is why juxtarenal angiography may also be done in refractory cases.16,17

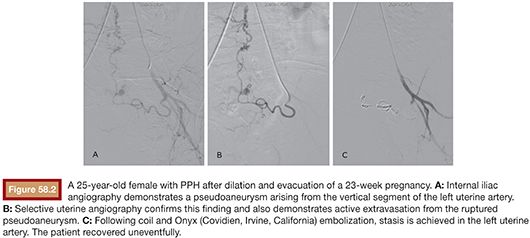

Embolization is most frequently performed using absorbable gelatin sponge to provide temporary occlusion.18 Blood flow typically returns after a few weeks as the surrounding tissues absorb the material. This transient blockage followed by recanalization of the artery has been observed to be adequate for control of the hemorrhage. Very small particles (i.e., microparticles) may cause uterine necrosis19 and are thus generally avoided. Nonabsorbable materials (e.g., polyvinyl alcohol particles) can be used to occlude distal vessels. Absorbable particles, on the other hand, block arterial flow more proximally.20 As in the original case by Brown et al.,12 Gelfoam has been the material of choice for these procedures and was the most common material used in the literature, as reviewed by Vedantham et al.,21 often in form of pledgets. Because the gravid uterus comprises a system of collateral vessels as opposed to a single, predominant vessel, coil embolization is not typically used.22 Large vessel lacerations may, however, necessitate the use of metal coils in a fraction of cases.23 Despite its higher cost and difficulty of use, embolization with N-butyl cyanoacrylate (NBCA) has also shown promise in patients with PPH, particularly in those who are at risk for or have already developed disseminated intravascular coagulation24 or at times of severe hemodynamic instability (Fig. 58.2).22

OUTCOMES

Emergency Embolization

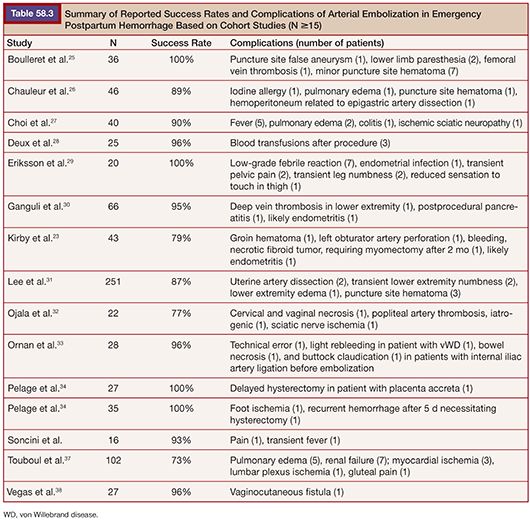

Most interventions in PPH are performed in an emergent setting due to the unpredictability of bleeding. Despite the lack of randomized trials on the topic, several retrospective and prospective cohort studies have examined the effectiveness of embolization in the emergency management of PPH.23,25–38 These studies have generally found the technique to be effective, with success rates ranging from 73% to 100%. Table 58.3 lists the studies since 1998 with at least 15 patients for emergency treatment of PPH with embolization. Lee et al.31 conducted the largest study to date on this topic. The authors performed a retrospective analysis of 251 women at their institution who underwent arterial embolization due to medically or surgically refractory primary PPH. Most commonly, both uterine arteries were embolized. Anterior divisions of the internal iliac arteries were embolized in cases of failure of response to uterine embolization or poor arterial access. They found the clinical and technical success rates of the embolization procedure to be 86.5% and 89.6%, respectively. Before these, there were also smaller reports of success with embolization in the literature.38–41 Several studies have, in fact, argued that embolization is underused.18,22,42,43

One of the challenges in the interpretation of the studies mentioned earlier is that PPH is clinically heterogeneous, which is difficult to standardize across reports.23,39 Patients often vary in the degree of severity of their bleeding. Touboul et al.37 for instance, included only severe PPH in their study, which may account for their low success rate of 73%. Primary and secondary PPH with various etiologies have also been intermixed in studies. Furthermore, Kirby et al.23 argued that clinical success has also not been uniform across different studies, as some have, for instance, included patients with postembolization rebleeding under clinical success. The efficacy of arterial embolization appears high, but large standardized studies, if not randomized trials, are needed to better assess its role in management of PPH (Table 58.3)

A debated topic in the field has been whether embolization should precede surgery or follow failed surgical attempts. In a systematic review of 46 studies, Doumouchtsis et al.39 compared the success rates of arterial embolization, balloon tamponade, uterine compression sutures, and iliac artery ligation or uterine devascularization and found all of these to be similar: 90.7%, 84.0%, 91.7%, and 84.6%, respectively. Embolization has been shown to be effective when done after surgery,40 but most studies conclude that embolization should be considered before surgical alternatives. In a small retrospective study, Bloom et al.41 directly compared embolization performed before versus after surgery and reported that the former may be preferred. When interventional radiology resources are available, embolization before surgery cannot only reduce rates of complications, intensive care unit admission, and blood transfusion requirements but also preserve fertility. More obvious advantages of embolization before surgery include avoidance of laparotomy and anesthesia.41 The recommendations by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) state that women can undergo embolization either due to excessive bleeding after hysterectomy or as an alternative to hysterectomy,42 but no definitive guidelines are present. Another related and open question regarding management of PPH with embolization is whether a patient should undergo embolization or surgery when hemodynamically unstable. ACOG recommends arterial embolization only in stable patients.42 Investigators speculate, nonetheless, that its role may become more important in time-sensitive cases with unstable patients23 and may be considered with close monitoring.31

Prophylactic Interventions in Abnormal Placentation

Interventional procedures play an important role not only in the emergency management of PPH but also in the prophylaxis of PPH in patients with high risk, particularly in the settings of abnormal placentation. Abnormal placentation has been rising in incidence due to higher rates of cesarean sections. There are various types of abnormal placentation. Placenta accreta occurs when the placenta is abnormally attached to the uterus. Invasion of the uterine musculature is termed placenta increta and that of the musculature, serosa, and sometimes neighboring structures is called placenta percreta.43 Patients with placenta previa, that is, a placenta located abnormally close to the cervix, are at higher risk for developing placenta accreta.

Abnormal placentation can be diagnosed during prenatal visits through assessment of risk factors and application of ultrasonography and MRI.44,45 On ultrasound, several findings can point to the diagnosis of placenta accreta. These include the presence of lacunae in the placental parenchyma with turbulent flow on color Doppler—the most reliable finding—placenta previa, reduced thickness of myometrium, and absence of a hypoechoic, retroplacental line (i.e., absence of clear space). The most consistent findings on MRI are bulging of the uterus, a heterogeneous placenta, and placental bands, which are dark on T2.46 Early prenatal diagnosis of abnormal placentation has allowed for the notion of prophylactic interventions for these high-risk pregnancies. The coordination of early diagnosis and preventive management requires a multidisciplinary approach between obstetricians and interventional radiologists at equipped facilities.

In 1992, Alvarez et al.47 studied prophylactic embolization in five patients, all of whom except one had placenta previa. Their study composed of a mixture of patients who underwent embolization either following failed medical and surgical management of PPH or following prophylactic placement of arterial catheters. The authors found that the prophylactic approach allowed for selective embolization of the affected internal iliac artery. Additionally, patients in the prophylactic group had reduced hospital stay and blood transfusion requirement when compared to the curative group.47 A more recent prospective study of 11 patients found prophylactic embolization to not only reduce risk of PPH but also increase fertility and decrease mortality and morbidity.48 In this study, embolization in women with placenta accreta was performed before placenta removal; in the case of placenta increta or percreta, the placenta was not removed. Due to the paucity of large comparison studies, it is difficult to conclude whether prophylactic embolization is always necessary and the procedure remains controversial. Soyer et al.,49 for instance, did not recommend this as they found emergency embolization in their cohort of 10 women to be sufficient and effective despite severe bleeding from abnormal placentation. Diop et al.50 compared the cases of emergency and preventive embolization in a mixed cohort of 17 patients and found reduced blood loss and delay time to embolization in the prophylactic group. The success rate of embolization, however, was 100% in both cases.

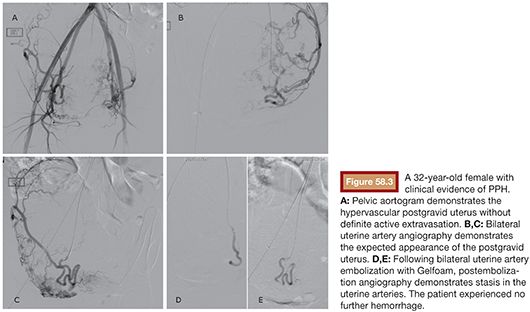

An alternative to the preoperative placement of catheters for embolization is the placement of occlusive balloon catheters for PPH prophylaxis, which may or may not precede arterial embolization (Fig. 58.3). This approach was introduced in 1997 by Dubois et al.,51 where internal iliac artery balloon catheterization and embolization during cesarean delivery and hysterectomy led to decreased blood loss. Since then, several cohort studies have investigated the role of prophylactic balloon catheterization in preventing PPH. The most recent and largest study in this area is a retrospective, case-control study by Ballas et al.,52 where preoperative, internal iliac artery balloon placement was compared to no intervention in 117 women with a diagnosis of placenta accreta confirmed by pathology. The investigators of this study compared several outcomes between the two groups, including estimated blood loss, blood transfusion units, massive transfusions, operative time, hospitalization duration, and complications. They found that patients with prophylactic balloon catheters experienced less blood loss and required less massive transfusions. The authors, therefore, concluded that the preventive procedure is safe and effective. Despite its large size, however, the study was not randomized, and it could not differentiate between the effects of balloon placement and prenatal placenta accreta diagnosis, which were highly correlated.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree