Fig. 6.1

Pelvic organ prolapse (POP). Weakness of the pelvic floor and supporting structures can result in POP (diagram on right) such as cystocele (orange arrow) and rectocele (blue arrow)

The Normal Female Pelvis

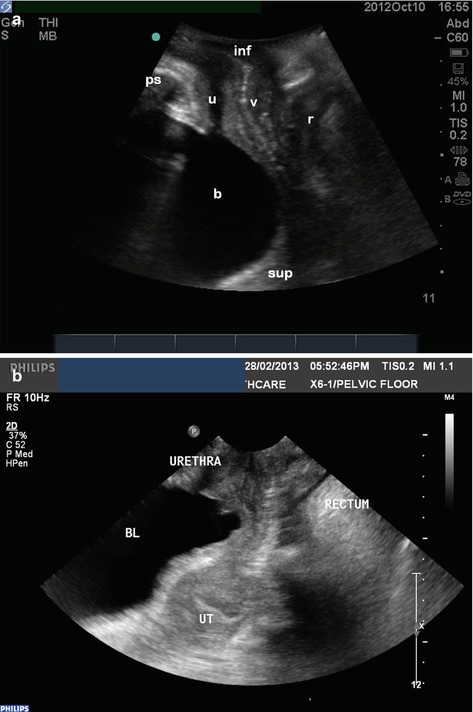

Figure 6.2 demonstrates the normal ultrasonic disposition of the female pelvic organs, namely, normal position of pubic symphysis, bladder, urethra, vagina, uterus, and rectum.

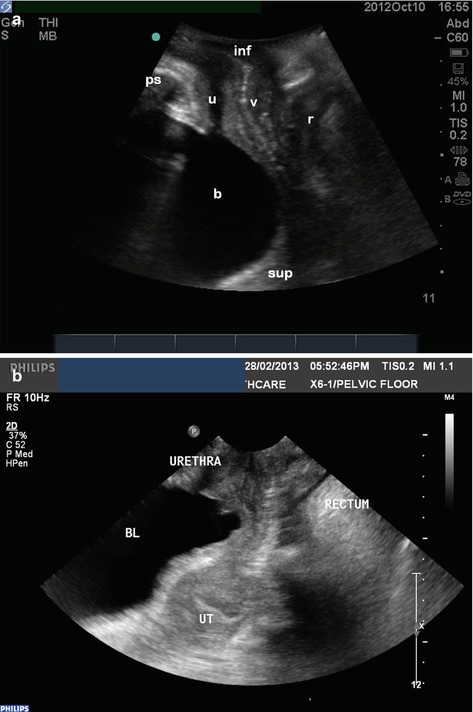

Fig. 6.2

(a, b) Sagittal transperineal ultrasound images demonstrating the three compartments of the pelvis. Bladder (b), urethra (u), vagina (v), rectum (r), pubic symphysis (ps), inferior/caudal (inf), superior/cranial (sup)

Practical Application of Ultrasound in Assessment of POP in Routine Clinical Practice

Although the use of pelvic ultrasound in assessing POP is not new and has been used in many academic centres in discovering and describing many anatomical defects utilizing many different research parameters [2–4], the pelvic floor reconstructive surgeon should also apply it in everyday clinical practice. One of the advantages of possessing ultrasound skills in routine clinical practice is that it can immediately add to the information which the clinician has already obtained in the history and physical examination. This advantage can come in the form of:

1.

Assisting the clinician in confirming what is seen on physical examination;

2.

More accurately delineating which organ(s) is prolapsed, especially in the posterior vaginal compartment when an enterocele component may not be immediately evident on physical examination;

3.

Confirming and detecting the presence of any previous mesh repairs, as well as the current position and anchor points of the mesh, both in the static and dynamic situation. This may help in evaluation of mesh erosion into urethra, bladder or bowel.

Armed with this extra information immediately available at the bedside, the reconstructive surgeon can better understand the disease process behind each vaginal compartment, correlate it with the patient’s symptomatology, and thus offer a more expedited and streamlined approach to management. In cases of recurrent POP after mesh repairs, ultrasound can often help the surgeon in understanding why the particular mesh failed, and this can allow the surgeon to reflect on whether it was a technical failure which he/she can improve on in future cases. This aspect has impact on quality improvement, continued professional development, and better patient care.

Technique of Transperineal Imaging of POP and Meshes (See Tips 6.1)

As for imaging mid-urethral slings, the transducer is placed on perineum, at the introitus (see Figs. 5.2 and 5.3). The bladder should be adequately filled. Valsalva manoeuvres are then used to assess the most dependent point of the prolapse in each of the three vaginal compartments so that a POP-Q assessment (Fig. 6.3) can be possible. Slings and pelvic organ prolapse meshes should be easily identified as a hyperechoic area in their respective areas (see Case 2). Scanning position should be in both supine and standing with full bladder if preferable, and take utmost care not to cause discomfort with pressure on the introitus which may also distort anatomy. Dynamic imaging will help to elicit location of the mesh, especially in failed cases, and to assess severity of the POP and how the mesh moves with straining.

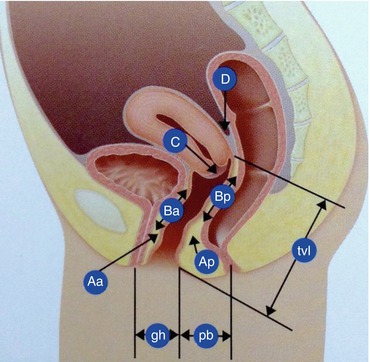

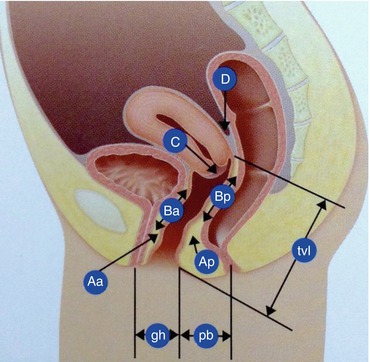

Fig. 6.3

POP-Q Quantification System (Image courtesy of American Medical Systems)

1. Ordinate system (Fig. 6.3) | |

Aa | Point on the anterior vaginal wall 3 cm from the hymen |

Ba | The leading point on the anterior wall at maximal Valsalva with reference to the hymen |

Ap | Point on the posterior vaginal wall 3 cm from the hymen |

Bp | The leading point on the posterior wall at maximal Valsalva with reference to the hymen |

C | Location of cervix or vaginal cuff with reference to the hymen

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|