Fig. 1

CT head showing traumatic SAH

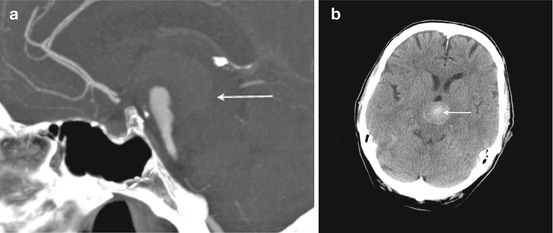

Fig. 2

Unenhanced axial CT brain showing central aneurismal SAH

Spontaneous SAH is most often (85 %) caused by a ruptured aneurysm. More rare causes include ruptured arteriovenous malformations at about 8 % and dural arteriovenous fistula at less than 1 %. This leaves about 5–10 % of cases in which no cause is found, and a venous rupture causing a perimesencephalic bleed is suspected. The importance of this latter group is that their risk of rebleeding is low and no definitive treatment is required. Due to the high rebleed rate in aneurismal SAH, urgent investigation and treatment has become the routine following the publication of the International Study of Aneurysm Treatment (ISAT), and this has led to the subsequent development of interventional neuroradiology and endovascular neurosurgery. Aneurysms can present with mass effect (Fig. 3a, b) or rarely with thromboembolic complication of the intraluminal thrombus.

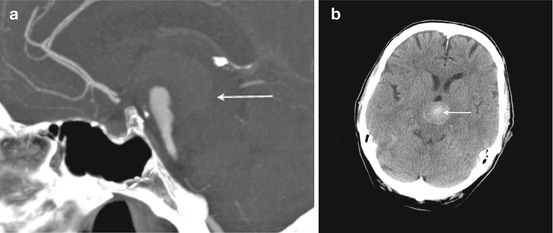

Fig. 3

(a) Sagittal maximum intensity projection (MIP) of a contrast-enhanced CT angiogram showing the mass effect of a giant basilar tip aneurysm that is substantially thrombosed. (b) Unenhanced axial CT brain showing the same aneurysm with high attenuation thrombus demonstrated near the aneurysm dome (arrow)

Risk Factors

Smoking

Hypertension

Alcohol abuse

Positive family history

Collagen dysfunction diseases

Female predominance over 30 years of age

Investigations

CT to Show SAH

Sensitivity for SAH at 24 h = 98 %

Sensitivity for SAH at 5 days = 70 %

Sensitivity for SAH at 7 days = 50 %

Lumbar Puncture (LP) to Show SAH in CT-Negative Cases and Delayed Presentation

Must be processed (spun down) by the lab immediately to decrease the false positive rate

98–100 % sensitive from 9 h to 2 weeks

70 % sensitive at 3 weeks

40 % sensitive at 4 weeks

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

T1, FLAIR, and gradient echo-/susceptibility-weighted imaging (SWI) sequences to look for blood

Computed Tomographic Angiography (CTA)

May miss small aneurysms at the skull base

Digital Subtraction Angiography (DSA)

Gold Standard with the best spatial and temporal resolution but comes at a cost of 1/2000 permanent neurological deficit

Endovascular Aneurysm Treatment (EVT)

Consent is the cornerstone of the patient–doctor relationship. It is important to cover:

Indications

Primary objective is to reduce the risk of rebleeding from 2 % per day to 0.2 % per year.

Secondary objectives are to allow aggressive hypertensive treatment for delayed cerebral ischemia.

Prevent recurrence.

Risks

5 % groin hematoma

2–4 % new neurological deficit (local data/ISAT)

Alternatives

Neurosurgical clipping

Conservative treatment

Special techniques

Preoperative Medication

Dual antiplatelet medication, used in the setting of unruptured aneurysms

World Health Organization (WHO) Checklist

Confirmation of the correct patient and procedure

Allergies

Risk factors for bleeding

Any special requirements

Review previous imaging

Performed under general anesthesia

Groin Puncture: Right, Left, or Both

Right normally, as close to the operator.

Left if indwelling lines already in the right or difficult access due to previously deployed stent, scar tissue, peripheral vascular disease, or bypass.

Both, check if angiography of both internal carotid artery (ICA) is needed e.g. while treating an anterior communicating artery complex aneurysm (Fig. 4a, b).

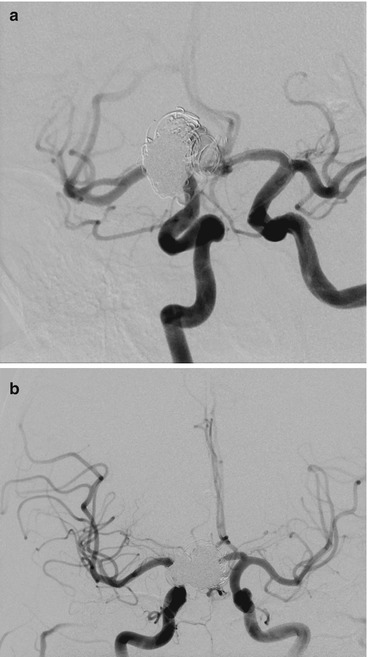

Fig. 4

(a, b) Shows dual ICA cannulation to allow contra lateral ACA control while coiling proceeds

Diagnostic Angiography

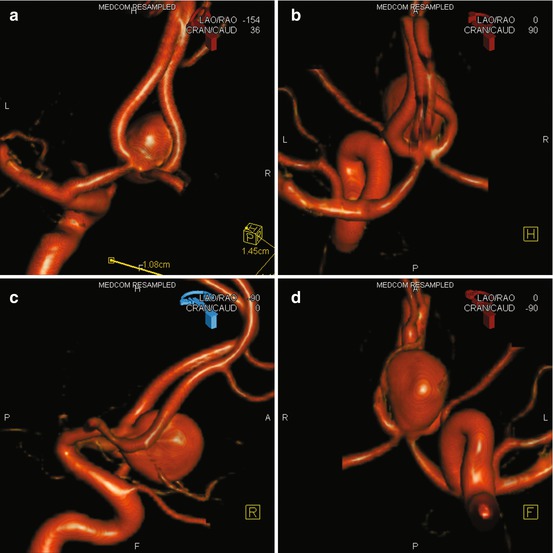

Target aneurysm harboring vessel first with an AP and lateral whole head with which to compare the pre- and post-embolization images looking for distal embolic events followed by a 3-dimensional (3-D) rotational angiogram (Fig. 5a–d) for the selection of working projections and measurement of the aneurysm neck and dome. The remaining vessels can then be interrogated while processing and manipulating the volume data.

Fig. 5

(a–d) Showing a 3-D rotational angiogram of an ACom aneurysm viewed from behind, above, laterally, and below, respectively

Guide Catheter

Stable safe position just below the skull base in the majority of cases on a heparin containing flush bag.

Intra-procedure Medication