Chapter 16 Principles of radiography of the head

Introduction

From the mid 1980s onwards there has been a reduction in the number of requests for plain radiography of the head, as computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in particular have provided more detailed and useful information (but plain radiography of the facial bones is still regularly requested). These imaging methods now provide information that is either unlikely to be provided by plain radiographic images or is only likely to be demonstrated by it in the later stages of disease processes. There has also been a reduction in the number of projections advocated per examination over the years, in order to reduce radiation dose to patients. Bearing in mind the superiority of MRI and CT, current guidelines do not recommend plain radiography of the cranial vault, even in cases of trauma, unless CT is not available at the time of examination; the exception to this is in cases of non-accidental injury in children.1

A logical approach to technique

Historically, texts on radiography have presented radiographers and students with information that has included up to approximately 50 projections.2,3 This has proved daunting for radiographers in training, to say the least, and it is possible that the decline in frequency of use of plain radiography of the head is likely to exacerbate this.

• Orbits and the bones forming the orbits

• Bones of the vault and sutures

• Sphenoid, including lesser and greater wings, sphenoid sinus, sella turcica and pterygoid processes/plates

• Petrous portion of temporal bone and its ridge

• Features of the mandible, temporomandibular joints

• External and internal auditory meati

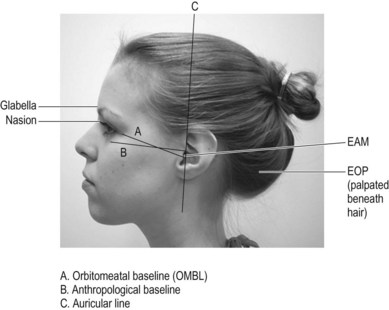

Description of basic projections relies heavily on the use of planes, baselines and surface markings, and the radiographer must be similarly familiar with these (Figs 16.1, 16.2).