Pulmonary Infection

Jeffrey S. Klein

Infection in the Normal Host

The bronchopulmonary system is open to the atmosphere and therefore is relatively accessible to airborne microorganisms. Multiple host defense mechanisms exist at the level of the pharynx, trachea, and central bronchi. When these mechanisms fail, pathogenic organisms can penetrate to the small distal bronchi and the pulmonary parenchyma. Once the invading organisms penetrate the parenchyma, there is activation of both the cellular and humoral immune systems. This response may manifest clinically and radiographically as pneumonia, and in a normal host it will often lead to eradication or at least suppression of the infecting organisms. If the immune response is impaired, a lower respiratory tract infection may lead to a very severe illness and often death, despite appropriate antibiotic therapy.

Mechanisms of Disease and Radiographic Patterns. Microorganisms responsible for producing pneumonia enter the lung and cause infection by three potential routes: via the tracheobronchial tree, via the pulmonary vasculature, or via direct spread from infection in the mediastinum, chest wall, or upper abdomen.

Infection via the tracheobronchial tree is generally secondary to inhalation or aspiration of infectious microorganisms and can be divided into three subtypes on the basis of gross pathologic appearance and radiographic patterns: lobar pneumonia, lobular or bronchopneumonia, and interstitial pneumonia (1). As will be discussed in later sections, certain organisms will typically produce one of these three patterns, although there is considerable overlap.

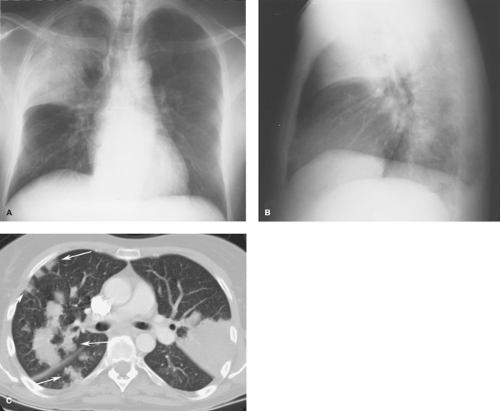

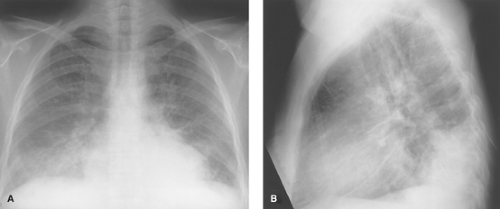

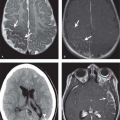

Lobar pneumonia is typical of pneumococcal pulmonary infection. In this pattern of disease, the inflammatory exudate begins within the distal airspaces. The inflammatory process spreads via the pores of Kohn and canals of Lambert to produce nonsegmental consolidation. If untreated, the inflammation may eventually involve an entire lobe (Fig. 16.1). Because the airways are usually spared, air bronchograms are common and significant volume loss is unusual (see Table 12.7).

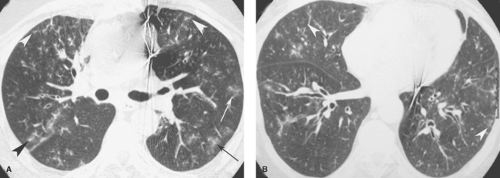

Lobular or bronchopneumonia is the most common pattern of disease and is most typical of staphylococcal pneumonia. In the early stages of bronchopneumonia, the inflammation is centered primarily in and around lobular bronchi. As the inflammation progresses, exudative fluid extends peripherally along the bronchus to involve the entire pulmonary lobule. Radiographically, multifocal opacities that are roughly lobular in configuration produce a “patchwork quilt” appearance because of the interspersion of normal and diseased lobules (Fig. 16.2). While bronchopneumonia is the most common cause of multifocal patchy airspace opacities, there is a broad list of differential diagnostic considerations (see Table 12.9). Exudate within the bronchi accounts for the absence of air bronchograms in bronchopneumonia. With coalescence of affected areas, the pattern may resemble lobar pneumonia.

In atypical pneumonia, as in viral and mycoplasma infection, there is inflammatory thickening of bronchial and bronchiolar walls and the pulmonary interstitium. This results in a radiographic pattern of airways thickening and reticulonodular opacities (see Table 12.12). Air bronchograms are absent because the alveolar spaces remain aerated. Segmental and subsegmental atelectasis from small airways obstruction is common.

The spread of infection to the lung via the pulmonary vasculature usually occurs in the setting of systemic sepsis. The pattern of parenchymal involvement is patchy and bilateral. The lung bases are most severely involved because blood flow is greatest in the dependent portions of the lungs. Pulmonary infection from direct spread usually results in a localized parenchymal process adjacent to an extrapulmonary source of infection. If an organism causes extensive parenchymal necrosis, an abscess may form.

Bacterial Pneumonia

Community-acquired bacterial pneumonia accounts for between 0.5 million and 1 million hospitalizations in the United States annually and is most often due to infection by Streptococcus pneumoniae, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydia pneumoniae, and Legionella pneumophila.

Gram-Positive Bacteria.

S pneumoniae (pneumococcus) is a gram-positive organism that may cause infection in healthy individuals but is much more commonly seen in the

elderly, alcoholics, and other compromised hosts. Patients with sickle cell disease or those who have undergone splenectomy are at particular risk for severe pneumococcal pneumonia.

elderly, alcoholics, and other compromised hosts. Patients with sickle cell disease or those who have undergone splenectomy are at particular risk for severe pneumococcal pneumonia.

Pneumococcal pneumonia tends to begin in the lower lobes or the posterior segments of the upper lobes. Initially there is involvement of the terminal airways, but rather than remaining localized to this site, there is rapid development of an airspace inflammatory exudate. The spread of infection to contiguous airspaces via interalveolar connections accounts for the nonsegmental distribution and homogeneity of the resultant consolidation.

The typical radiographic appearance of acute pneumococcal pneumonia is lobar consolidation (Fig. 16.1). Air bronchograms are usually evident. Cavitation in pneumococcal pneumonia is rare, with the exception of infections caused by serotype 3. Uncomplicated parapneumonic effusion or empyema may be seen in up to 50% of patients. With appropriate therapy, complete clearing may be seen in 10 to 14 days. In older patients or those with underlying disease, complete resolution may take 8 to 10 weeks.

Patients with pneumococcal pneumonia occasionally present with atypical radiographic patterns of disease. Patchy lobular opacities similar to those seen with bronchopneumonia (Fig. 16.1C), or rarely, a reticulonodular pattern, may be seen. In some patients, the atypical appearance may relate to the presence of preexisting lung disease (e.g., emphysema), partial treatment, or an impaired immune response (e.g., AIDS). In children, pneumococcal pneumonia may present as a spherical opacity (“round pneumonia”) simulating a parenchymal mass.

Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia is most common in hospitalized and debilitated patients. It may also develop following hematogenous spread to the lung in patients with endocarditis or indwelling catheters and in intravenous drug users. Community-acquired infection may complicate influenza or other viral pneumonias.

S aureus typically produces a bronchopneumonia and appears radiographically as patchy opacities (Fig. 16.3). In severe cases, the opacities may become confluent to produce lobar opacification. Because the inflammatory exudate fills the airways, air bronchograms are rarely seen. In adults, the process is often bilateral and may be complicated by abscess formation in 25% to 75% of patients. In patients who develop pulmonary infection from hematogenous seeding, one sees multiple bilateral poorly defined nodular opacities that eventually become more sharply defined and cavitate. Parapneumonic effusion and empyema are common. Pneumatocele formation is common in children and may lead to pneumothorax. Pneumatoceles may be distinguished from abscesses by their thin walls, rapid change in size, and tendency to develop during the late phase of infection.

Streptococcus pyogenes. Acute streptococcal pneumonia is rarely seen today, though it can occasionally complicate viral infection or streptococcal pharyngitis. Its radiographic appearance is similar to that of staphylococcal pneumonia, with lobular or segmental lower lobe opacities. The process may be complicated by abscess formation and cavitation; empyema is relatively common.

Bacillus anthracis. Anthrax is caused by a sporulating gram-positive bacillus that is distributed worldwide. Naturally occurring inhalational anthrax is rare; however, anthrax has been used as an agent of bioterrorism in the United States. The primary radiographic manifestations of inhalational anthrax are related to the underlying pathology of hemorrhagic lymphadenitis and mediastinitis accompanied by hemorrhagic pleural effusions. Conventional radiographs demonstrate mediastinal widening, hilar enlargement, and often pleural effusion. Frank areas of consolidation are not usually present but peribronchial opacities may be seen. CT scans of recent bioterrorism victims, performed in 2001 without intravenous contrast, demonstrated high-attenuation lymphadenopathy and pleural effusions secondary to hemorrhage. CT scans may show extensive adenopathy in the setting of normal radiographs and should be obtained if the suspicion of anthrax is high (2).

Gram-Negative Bacteria

Gram-negative bacteria are increasingly important causes of pneumonia in hospitalized patients, accounting for more than 50% of nosocomial pulmonary infections. While gram-negative organisms may be isolated from only a small percentage of healthy individuals, the isolation rate in hospitalized and severely ill patients ranges from 40% to 75%. The organisms most often responsible for pneumonia include members of the Enterobacteriaceae family (Klebsiella, Escherichia coli, and Proteus), Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Haemophilus influenzae, and L pneumophila (3).

The radiographic appearance of gram-negative bacterial pneumonia varies from small ill-defined nodules to patchy areas of opacification that may become confluent and resemble lobar pneumonia. Involvement is usually bilateral and multifocal, and the lower lobes are most frequently affected. Abscess formation and cavitation are relatively common. Parapneumonic effusion is common and is often complicated by empyema formation.

Klebsiella pneumoniae. Klebsiella pneumonia occurs predominantly in older alcoholic men and debilitated hospitalized patients. Radiographically it appears as a homogeneous lobar opacification containing air bronchograms. Three features help distinguish it radiographically from pneumococcal pneumonia: (1) the volume of the involved lobe may be increased by the exuberant inflammatory exudate, producing a bulging interlobar fissure; (2) an abscess may develop, with cavity formation, which is uncommon in pneumococcal pneumonia; and (3) the incidence of pleural effusion and empyema is higher. Pulmonary gangrene may be seen but is uncommon.

H influenzae. In adults, H influenzae infection is most common among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), alcoholism, and diabetes mellitus as well as those with an anatomic or functional splenectomy. It most often causes bronchitis, although it may extend to produce bilateral lower lobe bronchopneumonia.

P aeruginosa pneumonia most often affects debilitated patients, particularly those requiring mechanical ventilation. There is a high mortality associated with the disease. The radiographic pattern of parenchymal involvement depends upon the method by which the organisms reach the lung. Patchy opacities with abscess formation, which mimic staphylococcal pneumonia, are common when the infection reaches the lung via the tracheobronchial tree (Fig. 16.2). Diffuse, bilateral, ill-defined nodular opacities usually reflect hematogenous dissemination. Pleural effusions are common and are usually small.

L pneumophila. Legionnaires disease is caused by infection with L pneumophila, a gram-negative bacillus commonly found in air conditioning and humidifier systems. This infection tends to affect older men. Community-acquired infection is seen in patients with COPD or malignancy, whereas nosocomial infection primarily affects immunocompromised patients or those with renal failure or malignancy.

The characteristic radiographic pattern is airspace opacification, which is initially peripheral and sublobar. In some patients, the airspace opacities appear as a round pneumonia. The infection progresses to lobar or multilobar involvement despite the initiation of antibiotic therapy. At the peak of disease, the parenchymal involvement is usually bilateral. Pleural effusions are seen in approximately 30% of patients. Cavitation is not seen except in the immunocompromised patient (Fig. 16.4). The radiographic resolution of pneumonia is often prolonged and may lag behind symptomatic improvement.

Anaerobic Bacterial Infections

The majority of anaerobic lung infections arise from aspiration of infected oropharyngeal contents (4). Approximately 25% of patients give a history of impaired consciousness and many are alcoholic. The most common organisms responsible are the gram-negative bacilli Bacteroides and Fusobacterium, although the majority of pulmonary infections are polymicrobial. All anaerobic pulmonary infections produce a similar radiographic appearance. The distribution of parenchymal opacities reflects the gravitational flow of aspirated material. When aspiration occurs in the supine position, it is the posterior segments of the upper lobes and superior segments of the lower lobes that are predominantly involved, whereas aspiration in the erect position leads to involvement of basal segments of the lower lobes. The typical radiographic appearance is peripheral lobular and segmental airspace opacities. Cavitation within the areas of consolidation is relatively common, and discrete lung abscesses may be seen in up to 50% of patients. Hilar and/or mediastinal lymph node enlargement may be seen in those with lung abscesses. Empyema, with or without bronchopleural fistula formation, is a common complication and is seen in up to 50% of patients.

Atypical Bacterial Infections

Actinomycosis. Actinomyces israelii is an anaerobic gram-positive filamentous bacterium that is a normal inhabitant of the human oropharynx. It causes disease when it gains access to devitalized or infected tissues that facilitate its growth. Actinomycosis most commonly follows dental extractions, manifesting as mandibular osteomyelitis or a soft tissue abscess. The lungs may be infected by aspiration of infectious oral debris or, less commonly, by direct extension from the primary site of disease.

The radiographic pattern of actinomycosis is often indistinguishable from that of nocardiosis. Findings consist of nonsegmental airspace opacities in the periphery of the lower lobes. In some cases, the infection manifests as a localized mass-like opacity that mimics bronchogenic carcinoma (Fig. 16.5). If therapy is not instituted, a lung abscess may develop. Thoracic actinomycosis is characterized by its ability to spread to contiguous tissues without regard for normal anatomic barriers. Extension into the pleura will cause empyema, whereas chest wall involvement is characterized by osteomyelitis of the ribs

and chest wall abscess. Involvement of the ribs is seen as wavy periosteal reaction or lytic rib destruction (5). If the pleuropulmonary disease becomes chronic, extensive fibrosis may be seen. Rarely, the disease is disseminated and a miliary pattern is seen.

and chest wall abscess. Involvement of the ribs is seen as wavy periosteal reaction or lytic rib destruction (5). If the pleuropulmonary disease becomes chronic, extensive fibrosis may be seen. Rarely, the disease is disseminated and a miliary pattern is seen.

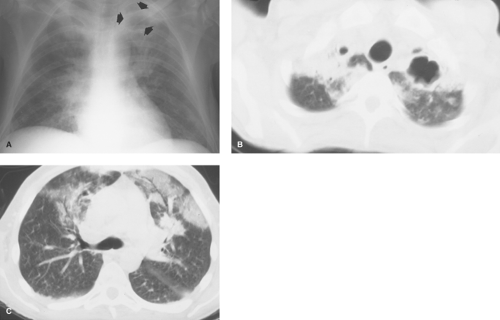

Mycoplasma pneumonia displays both bacterial and viral characteristics and is considered as a separate group (6). It is probably the most common atypical pneumonia and accounts for 10% to 30% of all community-acquired pneumonia. Affected patients usually have a subacute illness of 2 to 3 weeks’ duration. Symptoms include fever, nonproductive cough, headache, and malaise. Unusual physical findings include bullous myringitis and rash.

In the early stages of infection, interstitial inflammation leads to a fine reticular pattern on the chest radiograph. This may progress to patchy segmental airspace opacities (Fig. 16.6), which may coalesce to produce lobar consolidation. CT scan of mycoplasma pneumonia usually appears as patchy airspace opacities with a tree-in-bud appearance that reflects infectious bronchiolitis (Fig. 16.7). The process is often unilateral and tends to involve the lower lobes. Pleural effusion may be seen in the consolidative form of disease and occurs most commonly in children. Lymph node enlargement is uncommon but may be seen in children. Radiographic resolution may require 4 to 6 weeks.

Mycobacterial Infections

Mycobacterium tuberculosis is an aerobic acid-fast bacillus. Two principal forms of tuberculous pulmonary disease are recognized clinically and radiographically: primary tuberculosis (TB) and “reactivation” or postprimary disease. The inflammatory response to M tuberculosis differs from the normal response to bacterial organisms in that it involves cell-mediated immunity (delayed hypersensitivity). Initially, droplet nuclei laden with bacilli are inhaled and implanted in a subpleural location. In most patients, the bacilli are phagocytized and killed by alveolar macrophages. If the bacilli overcome the immune response of the host, an inflammatory focus is established. The macrophages are then transformed into epithelioid cells, which aggregate to form granulomas. The granulomas are usually well-formed by 1 to 3 weeks, coinciding with the development of delayed hypersensitivity. The granulomas typically demonstrate central caseous necrosis, thereby distinguishing them from the granulomas seen in sarcoidosis. Inflammation and enlargement of draining hilar and mediastinal lymph nodes is common in primary disease, particularly in children and immunocompromised patients.

In primary infection, the parenchymal disease and adenopathy may completely resolve, or there may be a residual focus of scarring or calcification. In some situations, usually in infants younger than 1 year, local parenchymal disease progresses and is termed progressive primary TB. More commonly, the disease will be contained by the granulomatous response and recur years later (reactivation or postprimary TB) in the setting of weakened host defenses from aging, alcoholism, diabetes, cancer, or HIV infection. Postprimary TB develops under the influence of hypersensitivity, with caseous necrosis seen histologically.

Primary TB has classically been a disease of childhood, although the incidence of primary disease has increased

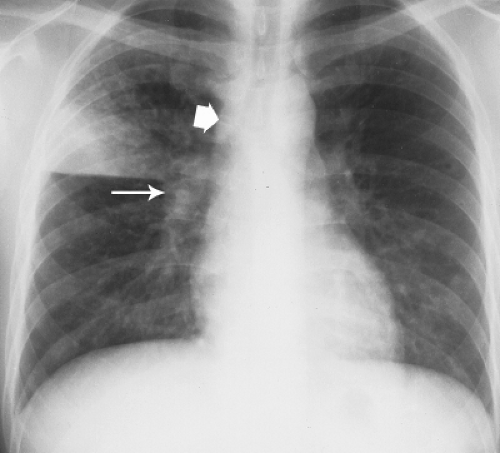

because of the HIV epidemic. Most patients with primary TB are asymptomatic and have no radiographic sequelae of infection. In some patients a Ranke complex, consisting of a calcified parenchymal focus (the Ghon lesion) and nodal calcification, is seen. If the patient is symptomatic, a nonspecific focal pneumonitis occurs and is seen as small, ill-defined areas of segmental or lobar opacification (Fig. 16.8). The parenchymal consolidation may mimic a bacterial pneumonia, but the clinical and radiographic course is much more indolent. Cavitation is relatively uncommon in the immunocompetent patient (7). The pulmonary focus may resolve completely or persist as a Ghon lesion or a Ranke complex. Tuberculomas are discrete nodular opacities that may develop in primary TB but are much more common in postprimary TB Unilateral pleural effusions are seen in 25% of cases and are usually associated with parenchymal disease. If a tuberculous empyema develops, it may break through the parietal pleura to form an extrapleural collection (empyema necessitatis). Unilateral hilar or mediastinal lymph node enlargement is common, particularly in children, and may be the sole radiographic manifestation of infection. Bilateral hilar or mediastinal lymph node enlargement may be seen, but this is uncommon and is almost invariably asymmetric in distinction to lymph node enlargement in sarcoidosis. During the primary tuberculous infection, there is hematogenous dissemination of the organism to regions with a high partial pressure of oxygen; these include the lung apices, renal medullae, and bone marrow. These microscopic foci are clinically silent and serve as a source of reactivation disease.

because of the HIV epidemic. Most patients with primary TB are asymptomatic and have no radiographic sequelae of infection. In some patients a Ranke complex, consisting of a calcified parenchymal focus (the Ghon lesion) and nodal calcification, is seen. If the patient is symptomatic, a nonspecific focal pneumonitis occurs and is seen as small, ill-defined areas of segmental or lobar opacification (Fig. 16.8). The parenchymal consolidation may mimic a bacterial pneumonia, but the clinical and radiographic course is much more indolent. Cavitation is relatively uncommon in the immunocompetent patient (7). The pulmonary focus may resolve completely or persist as a Ghon lesion or a Ranke complex. Tuberculomas are discrete nodular opacities that may develop in primary TB but are much more common in postprimary TB Unilateral pleural effusions are seen in 25% of cases and are usually associated with parenchymal disease. If a tuberculous empyema develops, it may break through the parietal pleura to form an extrapleural collection (empyema necessitatis). Unilateral hilar or mediastinal lymph node enlargement is common, particularly in children, and may be the sole radiographic manifestation of infection. Bilateral hilar or mediastinal lymph node enlargement may be seen, but this is uncommon and is almost invariably asymmetric in distinction to lymph node enlargement in sarcoidosis. During the primary tuberculous infection, there is hematogenous dissemination of the organism to regions with a high partial pressure of oxygen; these include the lung apices, renal medullae, and bone marrow. These microscopic foci are clinically silent and serve as a source of reactivation disease.

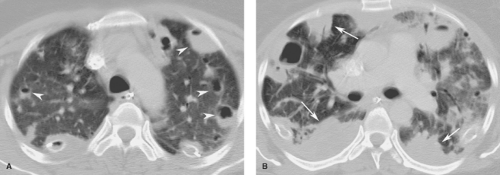

Post-primary TB patientsoften present with cough and constitutional symptoms, including chills, night sweats, and weight loss. Reactivation tends to occur in the apical and posterior segments of the upper lobes and the superior segments of the lower lobes. Ill-defined patchy and nodular opacities are commonly seen. Cavitation is an important radiographic feature of postprimary TB and usually indicates active and transmissible disease (Fig. 16.9). The cavitary focus may lead to transbronchial spread of organisms and result in multifocal bronchopneumonia. Erosion of a cavitary focus into a branch of the pulmonary artery can produce an aneurysm (Rasmussen aneurysm) and cause hemoptysis. With appropriate antimicrobial treatment, the disease is usually controlled by a granulomatous response. Parenchymal healing is associated with fibrosis, bronchiectasis, and volume loss (cicatrizing atelectasis) in the upper lobes.

There are several late complications of pulmonary TB. Interstitial fibrosis can cause pulmonary insufficiency and secondary pulmonary arterial hypertension. Hemoptysis may be secondary to bronchiectasis, mycetoma formation in an old tuberculous cavity, or erosion of a calcified peribronchial lymph node (broncholith) into a bronchus. Bronchostenosis is a result of healed endobronchial TB.

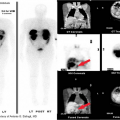

Miliary TB may complicate either primary or reactivation disease. It results from hematogenous dissemination of tubercle bacilli and produces diffuse bilateral 2- to 3-mm pulmonary nodules (Fig. 16.10). Miliary disease is associated with a high mortality and requires prompt therapy.

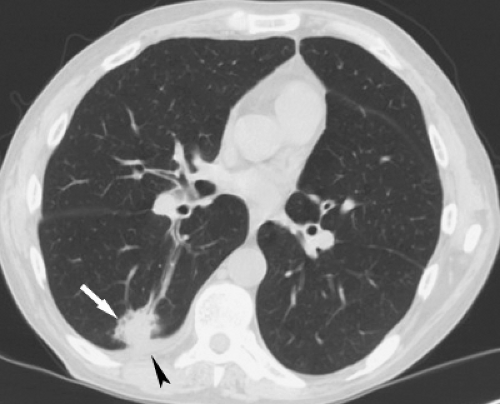

Atypical Mycobacterial Infections. There are several nontuberculous mycobacteria that may cause pulmonary disease (8). The most common organism responsible for pulmonary disease is Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare (MAI) or M kansasii. Disease in nonimmunocompromised patients typically

affects those with underlying COPD. The radiographic features are often indistinguishable from those of reactivation TB, with chronic fibrocavitary opacities involving the upper lobes. While cavitation is common, pleural effusion, lymph node enlargement, and miliary spread are distinctly unusual. A second pattern of disease with MAI has recently been described in middle-aged and elderly women, with small peribronchial nodules and bronchiectasis seen in a middle lobe and lingular distribution (Fig. 16.11). Although the disease caused by nontuberculous mycobacteria tends to be more indolent than that seen with M tuberculosis, it is often difficult to treat effectively.

affects those with underlying COPD. The radiographic features are often indistinguishable from those of reactivation TB, with chronic fibrocavitary opacities involving the upper lobes. While cavitation is common, pleural effusion, lymph node enlargement, and miliary spread are distinctly unusual. A second pattern of disease with MAI has recently been described in middle-aged and elderly women, with small peribronchial nodules and bronchiectasis seen in a middle lobe and lingular distribution (Fig. 16.11). Although the disease caused by nontuberculous mycobacteria tends to be more indolent than that seen with M tuberculosis, it is often difficult to treat effectively.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree