Tomás Franquet

Pulmonary Infection in Adults

Respiratory infections are the commonest illnesses occurring in humans, and pneumonia is the leading cause of death related to infectious disease and the sixth most common cause of death in the United States.1 Pneumonia is an acute infection of the pulmonary parenchyma that is associated with at least some symptoms of acute infection, accompanied by the presence of an acute infiltrate on a chest radiograph.2

Types of Pneumonias

Currently accepted clinical classification of pneumonia differentiates community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP), ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP), and health care–associated pneumonia (HCAP).3

Community-Acquired Pneumonia (CAP)

The diagnosis of CAP is based on the presence of a number of selected clinical features (e.g., cough, fever, sputum production and pleuritic chest pain) and is supported by imaging of the lung, usually by chest radiography.4

The spectrum of causative organisms of CAP includes Gram-positive bacteria such as Streptoccocus pneumoniae (pneumoccocus), Haemophilus influenzae and Staphyloccocus aureus, as well as atypical organisms such as Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydia pneumoniae or Legionella pneumophila and viral agents such as influenza A virus and respiratory syncytial viruses. Pulmonary opacities are usually evident on the radiograph within 12 h of the onset of symptoms.5

Hospital-Acquired Pneumonia (HAP)

Hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) may be defined as one occurring after admission to the hospital that was neither present nor in a period of incubation at the time of admission. Hospital-acquired pneumonia (nosocomial) is the leading cause of death from hospital-acquired infections and occurs most commonly among intensive care unit (ICU) patients, predominately in individuals requiring mechanical ventilation.

Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia (VAP)

Microorganisms responsible for VAP may differ according to the population of patients in the ICU, the durations of hospital and ICU stays, and the specific diagnostic method(s) used. The spectrum of causative pathogens of VAP in humans includes S. aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Enterobacteriaceae.6

Health Care-Associated Pneumonia (HCAP)

When pneumonia is associated with health care risk factors such as prior hospitalisation, dialysis, residing in a nursing home, and immunocompromised state, it is now classified as a health care-associated pneumonia (HCAP). The number of individuals receiving health care outside the hospital setting, including home wound care or infusion therapy, dialysis, nursing homes and similar settings, is constantly increasing.

Clinical Utility and Limitations of Chest Radiography and CT

A clinical diagnosis of pneumonia is usually established on the basis of clinical symptoms, laboratory findings and chest radiography. Though different patterns of pneumonia are associated with certain underlying micro-organisms, it has to be clearly stated that there is no specific radiological pattern of pneumonia caused by one particular microorganism. Overlap of imaging findings also with respect to course over time makes the differentiation of aetiologies based solely on the radiograph unreliable, and distinguishing pneumonia from conditions such as left heart failure and pulmonary embolism may sometimes be difficult,1,7 especially as patients with pre-existing lung disease (severe emphysema, interstitial lung disease, etc.) who may develop very atypical patterns of pneumonia.

New emerging pathogens have been recognised such as community-acquired methicillin-resistant S. aureus, human metapneumovirus, avian influenza A viruses (H5N1), coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and swine flu (H1N1).8,9

Chest radiography remains an important component of the evaluation of a patient with a suspicion of pneumonia, and usually is the first examination to be obtained.

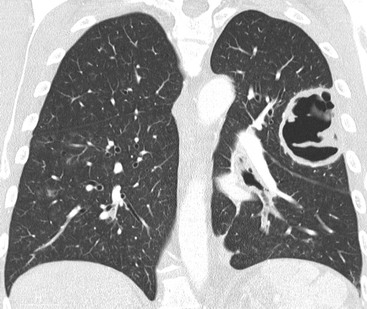

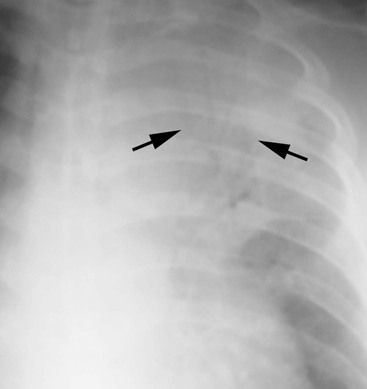

CT, preferably with thin (<2 mm thick) slices, has been shown to be more sensitive than radiography in the detection of subtle abnormalities and may show findings suggestive of pneumonia up to 5 days earlier than chest radiographs.10,11 CT is recommended in patients with clinical suspicion of infection and normal or non-specific radiographic findings (Fig. 12-1) and in patients with increased risk of pulmonary infection (e.g. neutropenia). CT is also indicated in patients with pneumonia and persistent or recurrent pulmonary opacities to diagnose or rule out underlying or alternative disease processes.

The presence of a radiographically visibile opacification is part of the definition of pneumonia, according to the American Thoracic Society (ATS),12 though there might be a time delay of several hours between onset of clinical symptoms and radiographic changes, and specific conditions may further the delay or cause a negative chest radiograph.

Regression of pneumonia over time varies with the underlying organism, patient comorbidity and patient age and can take between 1 and 2 weeks or up to 2 months.

Patterns of Pulmonary Infection

Pneumonias are usually divided, according to their chest imaging appearance, into lobar pneumonia, broncho- or lobular pneumonia and interstitial pneumonia.

In lobar pneumonia the inflammatory exudate begins in the distal air spaces adjacent to the visceral pleura, and then spreads via collateral air drift routes (pores of Kohn) to produce uniform homogeneous opacification of partial or complete segments of lung and occasionally an entire lobe. Occasionally, infection is manifested as a spherical focus of consolidation (Fig. 12-2). An air bronchogram is frequently seen. S. pneumoniae is by far the most common cause of complete lobar consolidation. Other causative agents that produce complete lobar consolidation include Klebsiella pneumoniae and other Gram-negative bacilli, L. pneumophila, H. influenzae, and occasionally M. pneumoniae.

Characteristic manifestations on CT are lobar or sublobar consolidations, sharply demarcated by the interlobar fissure.

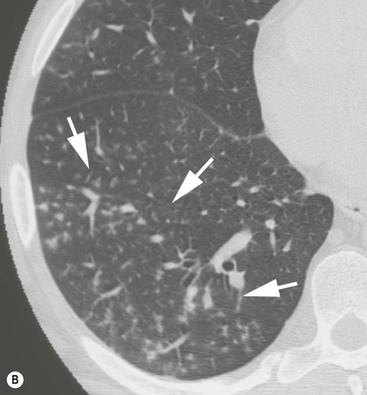

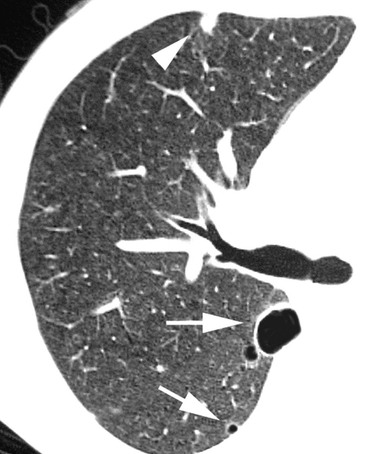

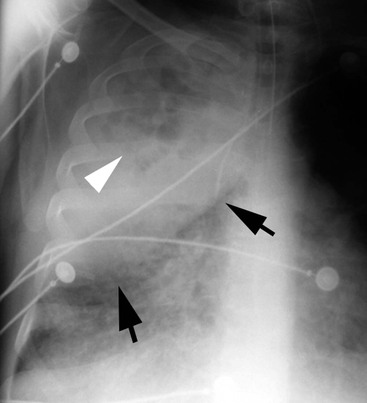

Bronchopneumonia (lobular pneumonia) is characterised histologically by predominantly peribronchiolar inflammation. Although initially patchy, progression of disease results in lobular and segmental consolidation13 (Fig. 12-3). An air bronchogram is usually absent. The most common causative organisms of bronchopneumonia are S. aureus, H. influenzae, P. aeruginosa, and anaerobic bacteria.

Characteristic manifestations of bronchopneumonia on CT include centrilobular ill-defined nodules and branching linear opacities, airspace nodules, and multifocal lobular areas of consolidation (Fig. 12-4).

The term atypical pneumonia (interstitial pneumonia) was initially applied to the clinical and radiographic appearance of lung infection not behaving or looking like that caused by S. pneumoniae. In the literature, the term ‘atypical pneumonia’ (as opposed to ‘bacterial pneumonia’) is still in wide usage, although technically incorrect. Many causative organisms are identified as bacteria, albeit unusual types (Mycoplasma is a type of bacteria without a cell wall and Chlamydia are intracellular parasites). It is therefore important to realise that the term ‘atypical pneumonia’—if more correctly based on the underlying type of causative pathogen—does not only refer to an interstitial pattern (Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia, certain viral infections but also infections presenting with dense consolidation such as Legionella, Mycoplasma, Chlamydia, etc).

The usual causes of interstitial pneumonia are viral and mycoplasmal infections that radiographically present with focal or diffuse small heterogeneous opacities uniformly distributed bilaterally in both lungs.

Complications of Pneumonia

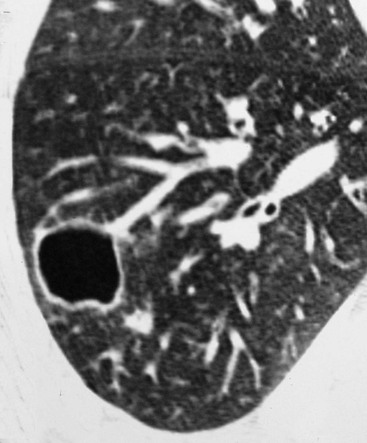

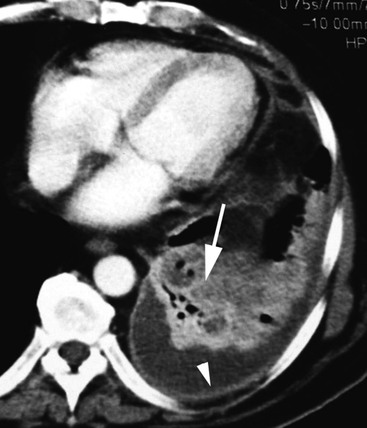

Lung abscess is defined as a localised necrotic cavity containing pus. The most common cause of lung abscess is aspiration.14 They occur most commonly in the posterior segment of an upper lobe or the superior segment of a lower lobe14 (Fig. 12-5). Common causes of lung abscess include anaerobic bacteria (most commonly Fusobacterium nucleatum and Bacteroides sp.), S. aureus, P. aeruginosa and K. pneumoniae.14,15

Pulmonary gangrene is an uncommon complication of pneumonia characterised by the development of fragments of necrotic lung within an abscess cavity (pulmonary sequestrum).16

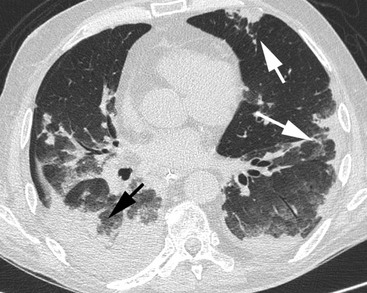

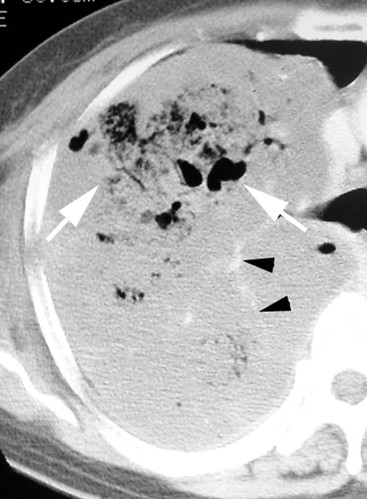

Pneumatocele is a thin-walled, gas-filled space that usually develops in association with infection.17 It presumably results from drainage of a focus of necrotic lung parenchyma followed by check-valve obstruction of the airway subtending it.18 The complication is caused most often by S. aureus in infants (Fig. 12-6) and children and by P. jiroveci in patients who have acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) (Fig. 12-7).

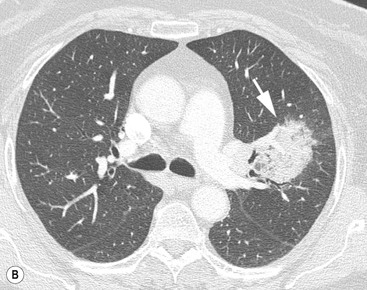

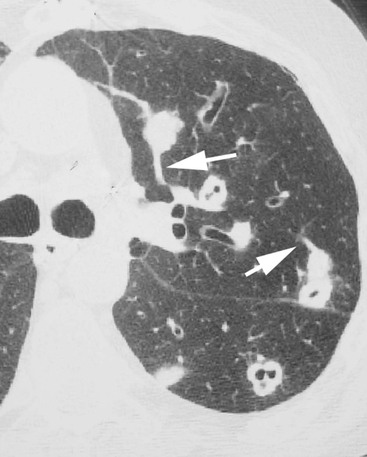

Septic emboli to the lungs originate in a variety of sites, including cardiac valves (endocarditis), peripheral veins (thrombophlebitis) and venous catheters or pacemaker wires. On cross-sectional CT images the nodules often appear to have a vessel leading into them (‘feeding vessel’ sign)19 (Fig. 12-8). Dependent on the underlying organism, nodules cavitate typically at different time points, resulting in the simultaneous appearance of solid nodules, and nodules with varying sizes of cavitations.

Empyema occurs in less than 5% of pulmonary infections. The pathogens traditionally associated with empyema are S. pneumoniae, Streptococcus pyogenes and S. aureus. Radiographically, early signs include obliteration of the costophrenic angle. Complete opacification of an hemithorax and contralateral mediastinal displacement may occur in large effusions. CT features include (a) pleural enhancement and thickening of the parietal pleura, (b) increased density of extrathoracic fat and (c) thickening and increased density of the extrapleural subcostal fat.

Bronchopleural fistula is a sinus tract between the bronchus and the pleural space that may result from necrotising pneumonias, lung surgery, lung neoplasms and trauma. Imaging features consist of (1) increase in intrapleural air space, (2) appearance of a new air-fluid level, (3) changes in an already present air-fluid level, (4) development of tension pneumothorax and (5) demonstration of actual fistulous communication on CT scan.20

Integrating Clinical and Imaging Findings

The clinician evaluating the patient with a known or suspected diagnosis of pulmonary infection faces a diagnostic challenge because of the majority of processes presenting with similar signs and symptoms, and the radiographic findings of a pneumonia do not provide a specific aetiological diagnosis. Furthermore, radiographic manifestations of a given infectious process may be variable, depending on the immunologic status of the patient as well as the pre- or coexisting lung disease.

The most useful imaging techniques available for the evaluation of the patient with known or suspected pulmonary infection are chest radiography and computed tomography.

Lobar Pneumonia

Most Common Organisms

Streptococcus pneumoniae.

Streptoccocus pneumoniae is responsible for approximately one-third of all cases of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP).21 Risk factors for the development of pneumococcal pneumonia include the extremes of age, chronic heart or lung disease, immunosuppression, alcoholism, institutionalisation and prior splenectomy.

The typical radiographic appearance of acute pneumoccocal pneumonia consist of a homogeneous consolidation that crosses segmental boundaries (non-segmental) but involves only one lobe (lobar pneumonia) (Fig. 12-9). The CT ‘angiogram sign’, initially described in the lobar form of bronchoalveolar cell carcinoma as the enhancement of branching pulmonary vessels in a homogeneous low-attenuation consolidation of lung parenchyma, may also occur in lobar pneumonia (Fig. 12-10).22 Occasionally, infection is manifested as a spherical focus of consolidation. Pleural effusion is common and is seen in up to half of patients.23,24

Klebsiella.

Klebsiella pneumoniae is among the most common Gram-negative bacteria, accounting for 0.5–5.0% of all cases of pneumonia. The radiographic features include bulging fissures due to volume increase of the infected lobe, sharp margins of the advancing border of the pneumonic infiltrate and early abscess formation (Fig. 12-11). CT findings consist of ground-glass attenuation, consolidation and abscess formation.25

Legionella sp.

Legionella is one of the most common causes of severe CAP in immunocompetent hosts. Human infection may occur when Legionella contaminates water systems, such as air conditioners and condensers. Risk factors for the development of L. pneumophila pneumonia include immunosuppression, post-transplantation, cigarette smoking, renal disease and exposure to contaminated drinking water. Patients with Legionella pneumonia usually present with fever, cough, initially dry and later productive, malaise, myalgia, confusion, headaches and diarrhoea.

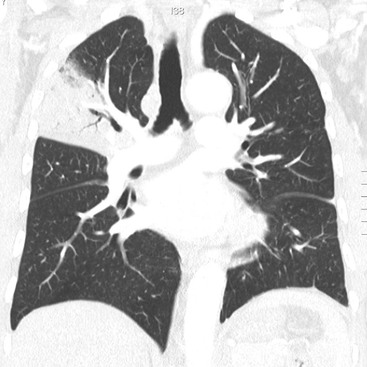

Imaging findings include peripheral airspace consolidation similar to that seen in acute S. pneumoniae pneumonia. In many cases, the area of consolidation rapidly progresses to occupy all or a large portion of a lobe (lobar pneumonia) to involve contiguous lobes or to become bilateral (Fig. 12-12). Occasionally, Legionella pneumonia may result in a round area of consolidation simulating a mass (round pneumonia).26 Pleural effusion may occur in 35 to 63% of cases.

Chlamydia.

Chlamydia pneumoniae (strain TWAR) is the most commonly occurring Gram-negative intracellular bacterial pathogen. It is frequently involved in respiratory tract infections and has also been implicated in the pathogenesis of asthma in both adults and children.27,28 On CT, C. pneumoniae pneumonia demonstrates a wide spectrum of imaging findings that are similar to those of S. pneumoniae pneumonia and M. pneumoniae pneumonia, consisting of areas of consolidation, bronchovascular bundle thickening, nodules, small pleural effusion, lymphadenopathy, reticular or linear opacities and airway dilatation (Fig. 12-13).

Moraxella catarrhalis.

Moraxella catarrhalis (formerly known as Branhamella catarrhalis) is an intracellular Gram-negative coccus currently considered the third most common cause of community-acquired bacterial pneumonia (after S. pneumoniae and H. influenzae). Moraxella catarrhalis seldom results in pneumonia in previously healthy individuals.29 Most patients with pneumonia (80 to 90%) have underlying COPD, and their clinical illness may be difficult to distinguish from exacerbations of lung disease by other causes. Chest radiographs show bronchopneumonia or lobar pneumonia that usually involves a single lobe (Fig. 12-14).

Immunocompromised Host

Nocardia sp.

Nocardia is a genus of filamentous Gram-positive, weakly acid-fast, aerobic bacteria that affects both immunosuppressed and immunocompetent patients. Nocardiosis usually begins with a focus of pulmonary infection and may disseminate through hematogenous spread to other organs, most commonly to the CNS. Imaging findings are variable and consist of unifocal or multifocal consolidation and single or multiple pulmonary nodules. Cavitation is common and lymphadenopathy or chest wall involvement may occur. Nocardia asteroides infection may complicate alveolar proteinosis30 (Fig. 12-15).

Actinomyces sp.

Thoracic actinomycosis is a chronic suppurative pulmonary or endobronchial infection caused by Actinomyces species, most frequently A. israelii, considered to be a Gram-positive branching filamentous bacterium. Actinomycosis has the ability to spread across fascial planes to contiguous tissues without regard to normal anatomic barriers. On CT, parenchymal actinomycosis is characterised by airspace consolidation with cavitation or central areas of low attenuation and adjacent pleural thickening31–33 (Fig. 12-16). Endobronchial actinomycosis can be associated with a foreign body (direct aspiration of a foreign body contaminated with Actinomyces organisms) or a broncholith (secondary colonisation of a pre-existing endobronchial broncholith by aspirated Actinomyces organisms).

Endemic in Certain Geographic Areas

Coxiella burnetii (Rickettsial Pneumonia).

The most common rickettsial lung infection is sporadic or epidemic Q-fever pneumonia caused by Coxiella burnetii, an intracellular, Gram-negative bacterium.

Infection is mainly acquired by inhalation from farm livestock or their products, and occasionally from domestic animals. Imaging findings consist of multilobar airspace consolidation, solitary or multiple nodules surrounded by a halo of ‘ground-glass’ opacity and vessel connection, and necrotising pneumonia.34

Francisella tularensis.

Tularaemia is an acute, febrile, bacterial zoonosis caused by the aerobic Gram-negative bacillus Francisella tularensis. It is endemic in parts of Europe, Asia and North America. Primary pneumonic tularaemia occurs in rural settings.35 Humans become infected after introduction of the bacillus by inhalation, intradermal injection or oral ingestion. Chest radiographic findings are scattered multifocal consolidations, hilar adenopathy and pleural effusion.

Bronchopneumonia

Most Common Organisms

Staphylococcus aureus.

Pneumonia caused by S. aureus usually follows aspiration of organisms from the upper respiratory tract.36 Risk factors for the development of staphylococcal pneumonia include underlying pulmonary disease (e.g. COPD, carcinoma), chronic illnesses (e.g. diabetes mellitus, renal failure) or viral infection. A severe pneumonia caused by community-associated methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) carrying genes for Panton–Valentine leukocidin has been described in healthy young adults.37

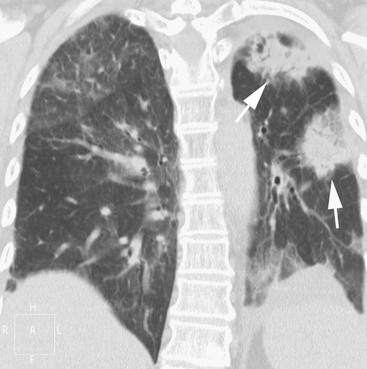

The characteristic pattern of presentation is as a bronchopneumonia (lobular pneumonia) that is bilateral in approximately 40% of patients38 Other features are cavitation, pneumatoceles, pleural effusions and spontaneous pneumothorax (Fig. 12-17). Pleural effusions occur in 30 to 50% of patients and abscesses develop in 15 to 30% of patients. The CT manifestations of S. aureus pneumonia include centrilobular nodules and branching opacities (tree-in-bud pattern), and lobular, subsegmental, or segmental areas of consolidation with or without abscess formation.

Escherichia coli.

Escherichia coli accounts for approximately 4% of cases of CAP and 5 to 20% of cases of HAP or HCAP. It occurs most commonly in debilitated patients.17

The radiographic manifestations usually are those of bronchopneumonia; rarely, a pattern of lobar pneumonia may be seen.39 Involvement usually is multilobar and predominantely in the lower lobes (Fig. 12-18).

Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

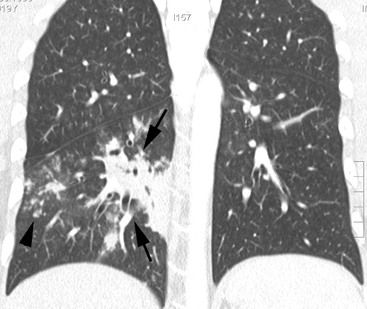

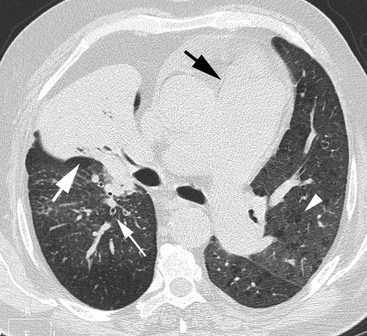

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a Gram-negative bacillus that is the most common cause of nosocomial pulmonary infection.40 It causes confluent bronchopneumonia that is often extensive and frequently cavitates. CT findings consist of multifocal, predominantly upper lobe, airspace consolidation, random large nodules, tree-in-bud opacities, ground-glass opacity, necrosis and pleural effusion (Fig. 12-19).

Haemophilus influenzae.

Haemophilus influenzae is a pleomorphic, Gram-negative coccobacillus that accounts for 5 to 20% of CAP in patients in whom an organism can be identified successfully. Factors that predispose to Haemophilus pneumonia include COPD, malignancy, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and alcoholism. The typical radiographic appearance of H. influenza pneumonia consists of multilobar involvement with lobar or segmental consolidation and pleural effusion (Fig. 12-20). In 30 to 50% of patients, the pattern is that of lobar consolidation similar to that of Streptococcus pneumoniae.41

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree