Chapter 3 Pulmonary Infections in the Normal Host

Clinical features are important in the determination of the etiologic agent of pneumonia (Table 3-1). Community-acquired pneumonias occurring in previously healthy individuals are caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae in 50% to 75% of cases and by Mycoplasma pneumoniae, viral organisms, or Legionella pneumophila. Nosocomial pneumonias (i.e., acquired in the hospital by patients who are already ill) typically are caused by gram-negative organisms or Staphylococcus aureus. Certain preexisting conditions are associated with pneumonias due to specific organisms. For example, patients with altered states of consciousness or those in coma are more likely to develop aspiration and subsequently develop infections due to mouth organisms (i.e., gram-negative organisms and anaerobes). S. aureus infection can occur after influenza pneumonia; in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), Haemophilus influenzae infection is common. S. aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa organisms are common superinfectants in patients with cystic fibrosis.

Table 3-1 Clinical Clues to the Cause of Pneumonia

| Clinical Circumstance | Likely Causative Organisms |

|---|---|

| Previously well, community-acquired | 50% to 75% due to Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcus), Mycoplasma pneumoniae, virus, or Legionella pneumophila |

| Hospital-acquired, otherwise ill | Gram-negative organisms, including Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Escherichia coli, and Enterobacter species; Staphylococcus aureus; less commonly, S. pneumoniae and Legionella |

| Alcoholism | S. pneumoniae most common; gram-negative organisms, anaerobes, and S. aureus frequent causes |

| Diabetes mellitus | Suspect gram-negative organisms and S. aureus |

| Altered consciousness, coma | Gram-negative organisms and anaerobes |

| Drug addiction | If not an AIDS patient, suspect Staphylococcus and gram-negative organisms |

| After influenza | S. aureus |

| Chronic bronchitis with exacerbation | Haemophilus influenzae (common) |

| Cystic fibrosis | Mucoid, P. aeruginosa |

From Woodring JH: Pulmonary bacterial and viral infections. In Freundlich IM, Bragg DG (eds): A radiologic approach to diseases of the chest. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1992.

CLASSIFICATION

Lobar Pneumonia

Radiographic Features

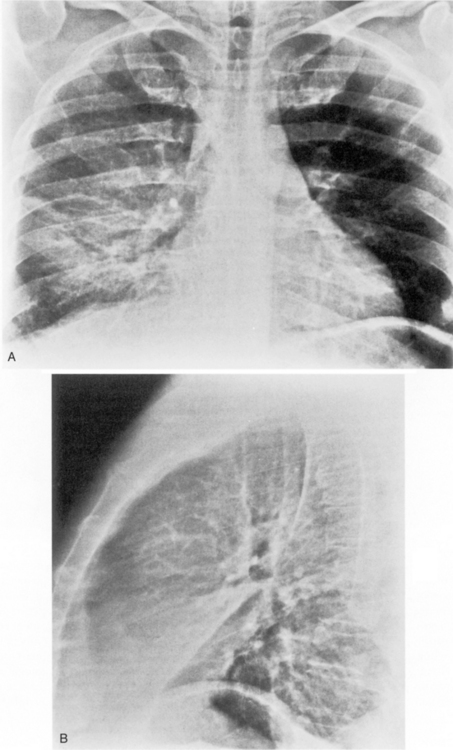

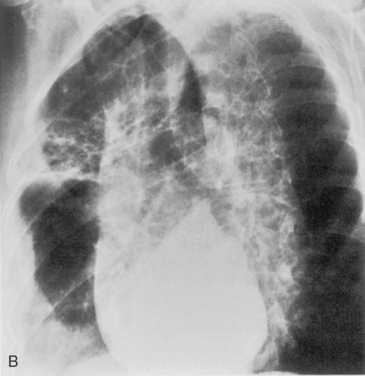

This type of pneumonia produces a pattern of confluent opacification, often with air bronchograms (Fig. 3-1). The entire lobe may be involved, but more frequently because of early use of antibiotics, the pneumonia involves only one or more segments within a lobe (i.e., sublobar form). A lobar pneumonia may result in expansion of the lobe due to voluminous edema, which is usually caused by infection with K. pneumoniae (Fig. 3-2). The enlargement of the lobe can be recognized radiographically by bulging of the interlobar fissures. Necrosis, cavitation, and development of a unique complication, pulmonary gangrene, may ensue.

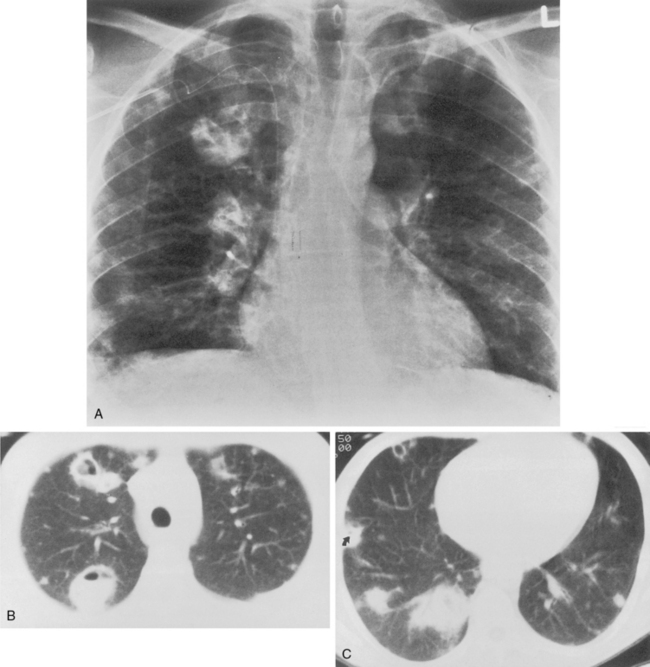

The computed tomography (CT) features of lobar pneumonia are similar to those seen on standard radiography (Fig. 3-3). There is usually evidence of confluent opacification with air bronchograms. The air bronchograms are often more easily visualized with CT examination. Table 3-2 summarizes the radiographic clues to the cause of pneumonia.

Table 3-2 Radiographic Clues to the Cause of Pneumonia

| Radiographic Finding | Likely Causative Organisms |

|---|---|

| Round pneumonia | Suspect Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcus) |

| Complete lobar consolidation | S. pneumoniae, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and other gram-negative bacilli; Legionella pneumophila and occasionally Mycoplasma pneumoniae |

| Lobar enlargement | K. pneumoniae, pneumococcus, Staphylococcus aureus, Haemophilus influenzae |

| Bilateral pneumonia (bronchopneumonia) | S. pneumoniae still common, but suspect others, including S. aureus, streptococci, gram-negative bacilli, anaerobes, L. pneumophila, virus, and aspiration syndromes |

| Interstitial pneumonia | Virus, M. pneumoniae, and occasionally H. influenzae, S. pneumoniae, and other bacteria |

| Septic emboli | Usually S. aureus; occasionally gram-negative bacilli, anaerobes, and streptococci |

| Empyema or bronchopleural fistula | S. aureus, gram-negative bacilli, anaerobes, and occasionally, pneumococcus; mixed bacterial infections common |

| Contiguous spread to chest wall | Actinomycosis; occasionally other bacteria or fungi |

| Cavitation | S. aureus, gram-negative bacilli, anaerobic bacteria, and streptococci; cavitation uncommon with S. pneumoniae or L. pneumophila |

| Pulmonary gangrene | K. pneumoniae, Escherichia coli, H. influenzae, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, S. pneumoniae, anaerobes, or fungi |

| Pneumatoceles | S. aureus, gram-negative bacilli, H. influenzae, M. tuberculosis, and measles; S. pneumoniae rare |

| Lymphadenopathy | M. tuberculosis, fungi, virus, M. pneumoniae, common bacterial lung abscess, and rarely plague, tularemia, and anthrax |

| Fulminant course with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) | Virus, S. aureus, streptococci, M. tuberculosis, and L. pneumophila |

From Woodring JH: Pulmonary bacterial and viral infections. In Freundlich IM, Bragg DG (eds): A Radiologic Approach to Diseases of the Chest. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1992.

Bronchopneumonia

Radiographic Features

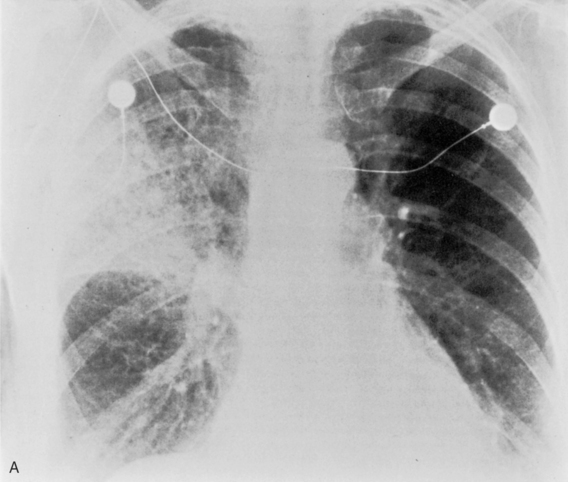

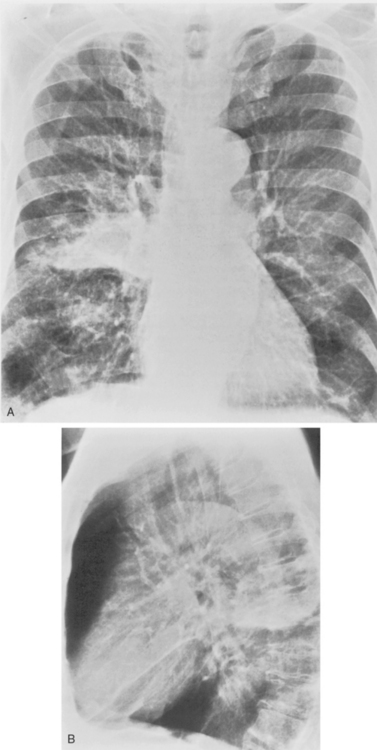

The radiographic appearance of bronchopneumonia pneumonia is most frequently that of multiple, ill-defined nodular opacities that are patchy but that may eventually become confluent and produce consolidation with airspace opacification (Fig. 3-4). The opacification may be multifocal and involve several lobes, or it may be diffuse. As the disease progresses, segmental and lobar opacification develops, similar to the pattern of a lobar pneumonia. Early necrosis and cavitation can occur. The nodular opacities of bronchopneumonia can be identified with facility on CT scans. The small nodules, usually less than 1 cm in diameter, represent peribronchiolar areas of consolidation or ground-glass opacity. They are called acinar or airspace nodules, but these nodules histologically are found in a peribronchiolar location. They are ill-defined and may be of homogenous soft tissue opacity and obscuring vessels, or they may be hazy and less dense so that adjacent vessels are clearly seen (i.e., ground-glass opacity). These nodules usually have a centrilobular location because of their proximity to small bronchioles.

Acute Interstitial Pneumonia

Radiographic Features

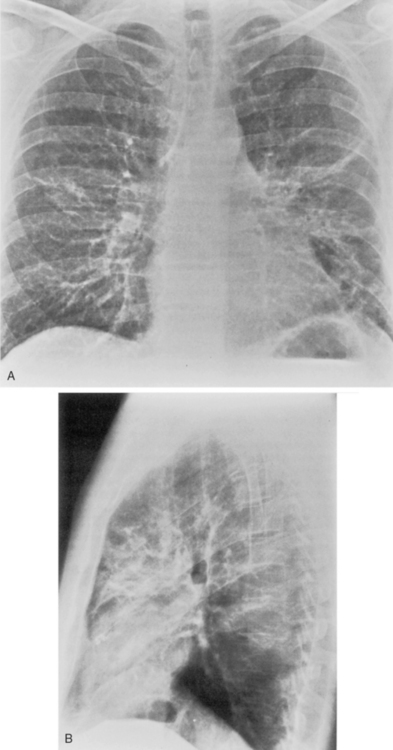

Bronchopneumonia or an acute interstitial pneumonia may be seen with viral infections (Fig. 3-5). The early radiographic appearance is that of thickening of end-on bronchi and tram lines. However, this often evolves into a reticular pattern that may be seen extending outward from the hila.

Hematogenous Spread of Infection

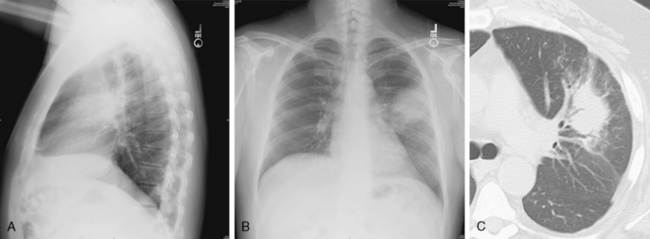

Radiographic Features

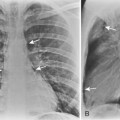

Septic infarcts tend to be multiple and peripheral and to abut the pleural surface. They occur more frequently in the lower lobes. These nodules or wedge-shaped opacities may show evidence of cavitation (Fig. 3-6). CT often demonstrates a vessel connected to the area of infarction. On CT, the septic infarcts appear as wedge-shaped, peripheral opacities abutting the pleura. They may contain air bronchograms or rounded lucencies of air, sometimes referred to as pseudocavitation. True cavitation is common. Occasionally, septic bacterial infection may result in diffuse massive seeding of the lungs with a miliary pattern (i.e., very small nodular pattern), although this is much more common with hematogenous dissemination of granulomatous infections.

COMPLICATIONS OF PNEUMONIA

Box 3-1 outlines the complications of pneumonia.

Cavitation

Necrosis of lung parenchyma with cavitation (Fig. 3-7) may occur in pneumonia, particularly that produced by virulent bacteria, including S. aureus, streptococci, gram-negative bacilli, and anaerobic bacteria. If the inflammatory process is localized, a lung abscess will form. It is usually rounded and focal, and it appears to be a mass (Fig. 3-8). With liquefaction of the central inflammatory process, a communication may develop with the bronchus; air enters the abscess, forming a cavity, which often contains an air-fluid level. The walls of the cavity may be smooth, but more often, they are thick and irregular.

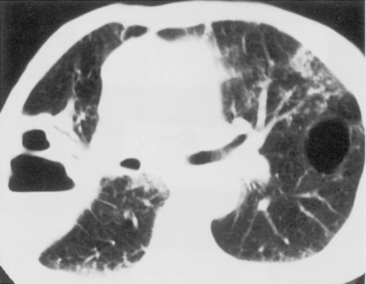

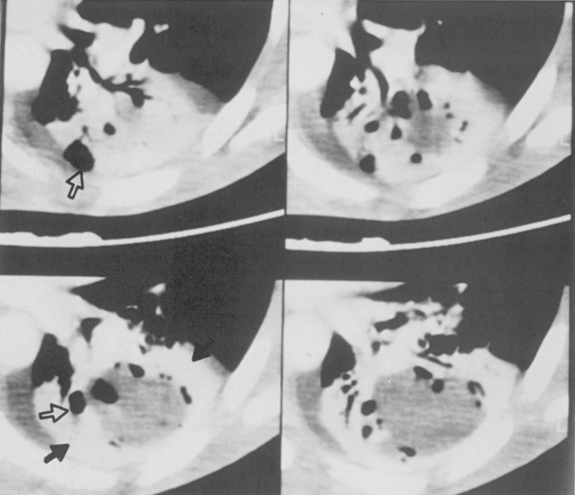

Multiple, small cavities or microabscesses may develop in necrotizing pneumonia (Fig. 3-9). They are recognized as multiple areas of lucency within a consolidated lobe or segment. A similar appearance may be produced by consolidation superimposed on areas of preexisting emphysema. If the necrosis is extensive, arteritis and vascular thrombosis may occur in an area of intense inflammation, causing ischemic necrosis and death of a portion of lung. This is a particular complication of Klebsiella pneumonia and other pneumonias producing lobar enlargement. The radiographic features include multiple areas of cavitation, often with air-fluid levels. Portions of dead lung may slough and form intracavitary masses.

Pneumatocele Formation

Pneumatoceles are usually associated with pneumonia caused by virulent organisms; the classic offender is S. aureus (Fig. 3-10). They usually form subpleural collections of air, which result from alveolar rupture. Radiographically, they appear as single or multiple, cystic lesions with thin and smooth walls. They may show rapid change in size and location on serial radiographs.

Pleural Effusions and Empyema

Pleural effusion is a common complication of pneumonia, occurring in about 40% of cases (Fig. 3-11). Most effusions are parapneumonic, but infection of the pleural space with empyema requiring drainage is an important but uncommon complication of some pneumonias. Empyemas can be recognized by the presence of gross pus within the pleural space, by a white blood cell count in the pleural fluid of greater than 15,000 cells/mm3, by the presence of bacteria within the pleural fluid, or by a pH less than 7.2. Chapter 18 provides more detail on the pleural complications of pneumonia.

Parenchymal necrosis in an underlying pneumonia may produce a fistula between the bronchus and the pleural space (i.e., bronchopleural fistula), and this results in an empyema with an air-fluid level. Further discussion of these entities can be found in Chapter 18.

PNEUMONIAS CAUSED BY GRAM-POSITIVE BACTERIA

Streptococcus pneumoniae

S. pneumoniae (Box 3-2) is responsible for one third to one half of community-acquired pneumonias in adults. These infections occur more frequently in the winter and early spring. Pneumococcal pneumonia occurs in healthy people, but it is much more common in alcoholic, debilitated, and other immunocompromised individuals.

The radiographic features include consolidation that is usually unilateral, although it may be bilateral, and it typically affects the lower lobes (see Fig. 3-1). Although it is a lobar pneumonia, it is uncommon for the lobe to be completely consolidated. Cavitation is rare, and large pleural effusions are uncommon. When present, they suggest the development of empyema. Sometimes, especially in children, the pneumonia may have a rounded, masslike appearance (Fig. 3-12). This is called a round pneumonia; it results from centrifugal spread of the rapidly replicating bacteria by way of the pores of Kohn and canals of Lambert from a single primary focus in the lung.

Staphylococcus aureus

S. aureus (Box 3-3) is a gram-positive coccus, and the spherical organisms occur in pairs and clusters. This pneumonia rarely develops in healthy adults, but it is sometimes a complication of viral infections and is much more common in infants and children. In infants, unilateral or bilateral consolidation involving the lower lungs is the most frequent radiographic presentation. Pneumatoceles, thin-walled cysts filled with air or partially filled with fluid, may develop and occasionally rupture into the pleural space, resulting in pneumothorax. In adults, the disease is usually bilateral and is preceded by an atypical pneumonia such as influenza. Cavitation is a common feature, and the cavities may be multiple, thick walled, and irregular (Fig. 3-13). There is a high incidence of large pleural effusions, and empyema resulting from bronchopleural fistula is a common complication. Methicillin resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) pneumonia usually occurs as a nosocomial infection in health care centers particularly in older, immunocompromised or intensive care unit patients.

Streptococcus pyogenes

Streptococci (Box 3-4) are gram-positive cocci that occur in pairs and chains. The pneumonia occasionally occurs in epidemic proportions. This form of pneumonia is much less common than that caused by Staphylococcus or S. pneumoniae (pneumococcus).

PNEUMONIAS CAUSED BY GRAM-NEGATIVE AEROBIC ORGANISMS

Klebsiella pneumoniae

Klebsiella pneumonia (Box 3-5) usually occurs in middle-aged or elderly patients, in those with underlying chronic lung disease, and in alcoholic individuals. Radiographic features consist of an upper lobe consolidation. Cavitation is common, and the lobar consolidation may lead to an expanded lobe with bulging interlobar fissures (see Fig. 3-2). If necrosis is extensive, pulmonary gangrene may develop.

Escherichia coli

E. coli pneumonia (Box 3-6) may be caused by direct extension from the gastrointestinal or genitourinary tract across the diaphragm or result from bacteremia. As is true of most of the gram-negative pneumonias, it is frequently characterized by the development of necrosis and multiple cavities. The lower lobes are more frequently involved.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa

P. aeruginosa pneumonia (Box 3-7) usually occurs in hospitalized patients, particularly those with debilitating disease (see Fig. 3-9). Organisms that affect the lungs often result from contamination of suction and tracheostomy devices. Radiographic features include a lower lobe predilection. However, the consolidation may spread rapidly to affect both lungs. Pleural effusions are uncommon. Multiple, irregular nodules may develop and are usually associated with bacteremia. These nodules may cavitate.

ASPIRATION PNEUMONITIS AND ANAEROBIC PNEUMONIA

Pulmonary aspiration (Box 3-9) is a common clinical problem. Many conditions predispose persons to aspiration, including reduced levels of consciousness, alcoholism, drug addiction, esophageal disease, periodontal and gingival disease, seizure disorders, and nasogastric tubes.

Box 3-9 Aspiration Pneumonitis and Anaerobic Pneumonia

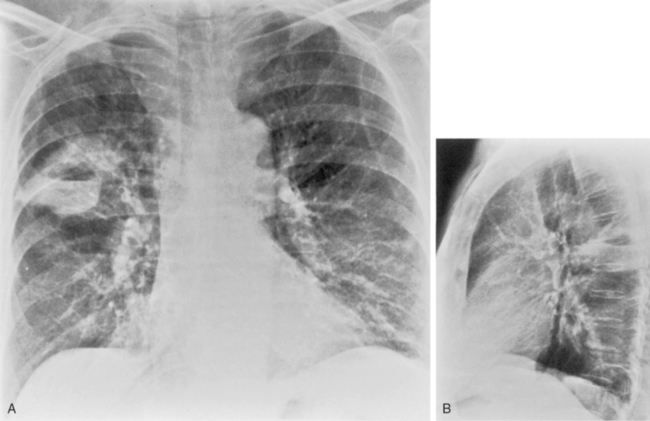

Ninety percent of aspiration pneumonias and lung abscesses are caused by anaerobic organisms. The pathogens include Prevotella, Bacteroides, Fusobacterium, and Peptostreptococcus. Because of the presence of oxygen in the lung, the progression of anaerobic infection is slow, beginning in the dependent lung zones. If the patient is in a supine position when the aspiration occurs, the superior segments of the lower lobes are most commonly affected, with the right side affected more frequently than the left (Fig. 3-14). Aspiration can also affect the posterior segments of both upper lobes. Chronic or recurrent aspiration, particularly in patients who are in the upright position, usually results in consolidation involving the basilar segments of the lower lobes. The middle lobe and lingula are uncommon sites for aspiration pneumonia. Aspiration is the most common cause of a primary lung abscess (see Fig. 3-8).

ATYPICAL PNEUMONIA SYNDROME

Atypical pneumonia syndrome (Box 3-10) describes pneumonias that do not respond to usual empiric antimicrobial therapy or do not have clinical features distinctive from the usual bacterial pathogens responsible for community-acquired pneumonias. Originally, these atypical pneumonias were thought to be caused by viruses. However, other treatable organisms have emerged as important causes of atypical pneumonia, including M. pneumoniae, L. pneumophila, and Chlamydia. These nonviral, atypical pneumonias are for the most part readily treatable with antibiotics.

Mycoplasma pneumoniae

M. pneumoniae (Box 3-11) accounts for approximately 20% of all cases of pneumonia. It usually occurs during the winter months in enclosed populations, such as students in college dormitories. The incubation period is 2 to 3 weeks, and the onset is often insidious, with low-grade fever and nonproductive cough. Extrapulmonary manifestations may include otitis, nonexudative pharyngitis, and diarrhea.

The radiographic features are usually those of a fairly diffuse, interstitial, fine reticulonodular pattern. This may evolve to patchy airspace consolidation, particularly in the lower lobes (Fig. 3-15). Hilar adenopathy is seen in approximately 20% to 40% of patients. The radiographic appearance is very similar to that of many viral infections. The diagnosis is made by serologic evaluation.