Chapter 11 Pulmonary Neoplasms

BENIGN NEOPLASMS AND OTHER NONNEOPLASTIC TUMORS

Hamartoma

Characteristics

Hamartomas (Box 11-1) are acquired lesions composed of tissues normally found within the organ, but they demonstrate disorganized growth. Hamartomas, the most common benign tumors of the lung, account for 5% to 8% of solitary pulmonary nodules.

Clinical Features

The peak incidence occurs in the sixth decade of life, with an age range of 30 to 70 years. The lesions are slightly more predominant in women. Most patients are asymptomatic, and the hamartoma is discovered on a routine chest radiograph as a solitary pulmonary nodule. Occasionally, hamartomas can occur endobronchially and may produce obstructive symptoms (see Chapter 13).

Radiographic Features

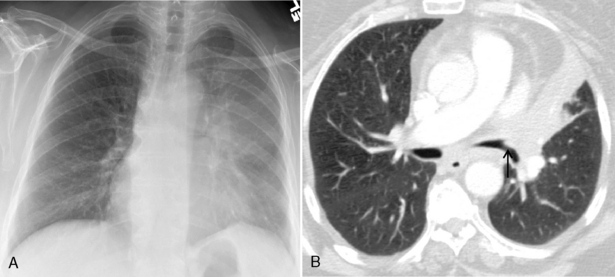

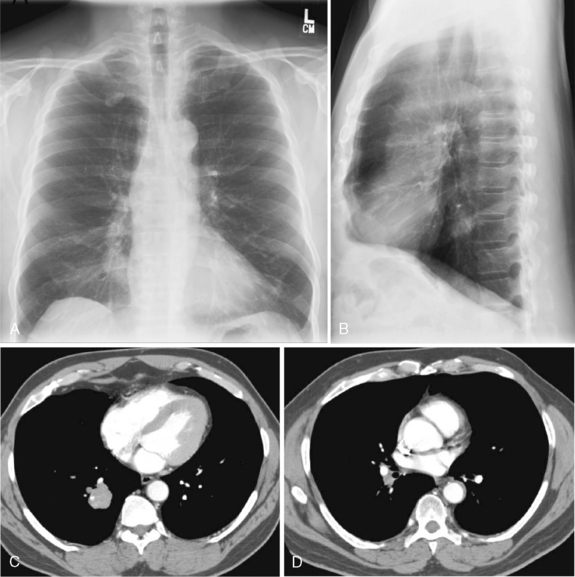

Characteristically, hamartomas appear as well-defined, solitary, spherical nodules or masses. They are usually less than 4 cm in diameter, and they have well-defined margins. Calcification is seen in 10% to 15% of cases on standard radiographs, although it is more frequently identified on CT. The calcification has a characteristic morphology that produces a popcorn appearance (Fig. 11-1). Hamartomas typically grow slowly, and in rare cases, they can be multiple.

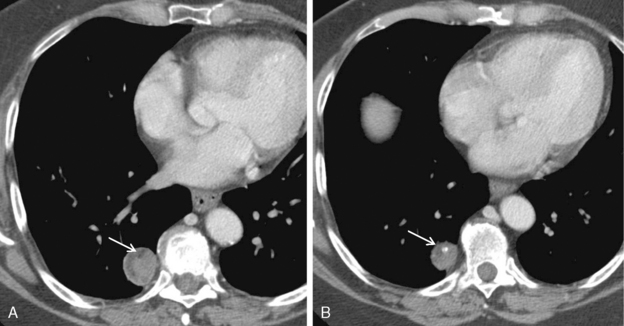

Thin-collimation CT can be valuable in diagnosing pulmonary hamartomas. The presence of focal deposits of fat (−50 to −150 HU) is most helpful in making this diagnosis (Fig. 11-2). In approximately 25% of cases, calcification can be identified.

Amyloid

Characteristics

Amyloid, a waxy pink material that stains with Congo red, has a typical birefringence with polarization microscopy (Box 11-2). It occurs in two major forms: primary and secondary. Lung involvement in primary amyloidosis is estimated to occur in 30% to 90% of cases. Secondary amyloidosis is usually associated with rheumatoid arthritis, suppurative disease such as osteomyelitis, and malignant neoplasms. Amyloidosis may also be associated with multiple myeloma. In the thorax, amyloid occurs in two locations. The first is the tracheobronchial tree. Airway amyloidosis is discussed in Chapter 12. Amyloidosis may also involve the lung parenchyma in a nodular form or as a diffuse, infiltrative process.

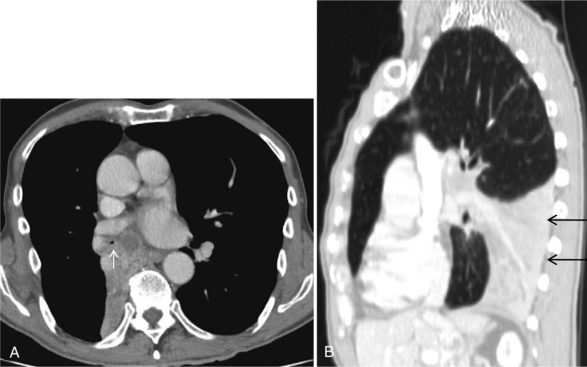

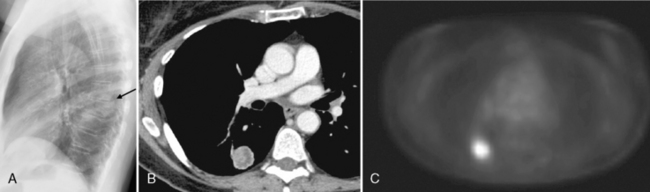

Radiographic Features

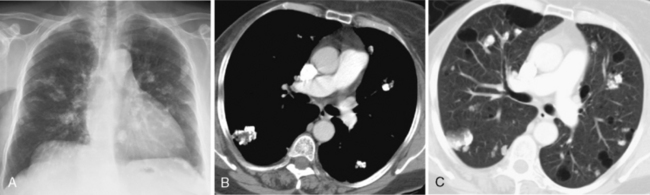

The radiologic appearance of the nodular form consists of solitary or multiple nodules and masses (Fig. 11-3). Calcification is common, occurring in 30% to 50% of patients, but cavitation is rare. The lower lobes are more frequently involved, often in a subpleural distribution. These nodules may exhibit slow growth.

In the diffuse, infiltrative form, bilateral and fine linear, nodular, or reticulonodular patterns may be present (Fig. 11-4). There is no specific distribution in the lung parenchyma. Associated nodal calcification may be identified.

Pulmonary Pseudotumor

Characteristics

Pulmonary pseudotumors include a number of histologic entities, such as plasma cell granuloma, inflammatory pseudotumor, histiocytoma, xanthoma, and mast cell granuloma (Box 11-3). The cause of pulmonary pseudotumors is unknown, although they were thought to represent a localized form of organizing pneumonia in patients with subclinical infection. Plasma cell granuloma is discussed more extensively in Chapter 9. Pulmonary pseudotumors occur slightly more frequently in males than in females over a wide age range. Patients are often asymptomatic, and antecedent infection can be documented in less than one fifth of cases.

Radiographic Features

Pulmonary pseudotumors manifest as solitary, peripheral pulmonary nodules that are well marginated (Fig. 11-5). Calcification occurs in about one fifth of cases, and airway involvement is uncommon. Rarely, particularly in children, these tumors may invade adjacent structures. Airway involvement is unusual.

LUNG CANCER

Clinical Features

Certain occupational agents may increase the risk of lung cancer, and they are listed in Box 11-4. The most important of these is asbestos. A combination of asbestos exposure and cigarette smoking is multiplicative and results in a marked increased risk of lung cancer, particularly if asbestosis is present in the parenchyma of the lungs. Most of the concomitant lung diseases associated with bronchogenic carcinoma reflect the presence of fibrosis in the lungs (Box 11-5), including any cause of end-stage lung disease, such as idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, and localized fibrosing disease, such as tuberculosis.

Only 10% of patients with lung carcinoma are asymptomatic (Box 11-6). Most often, symptoms are caused by central tumors that result in obstruction of a major bronchus. This leads to cough, wheezing, hemoptysis, and postobstructive pneumonia. Local intrathoracic spread may result in related symptoms, such as pleuritic or chest wall pain, Pancoast syndrome, and symptoms related to obstruction of the superior vena cava. Occasionally, patients may have symptoms that result from distant metastases (i.e., a seizure related to metastases to the brain).

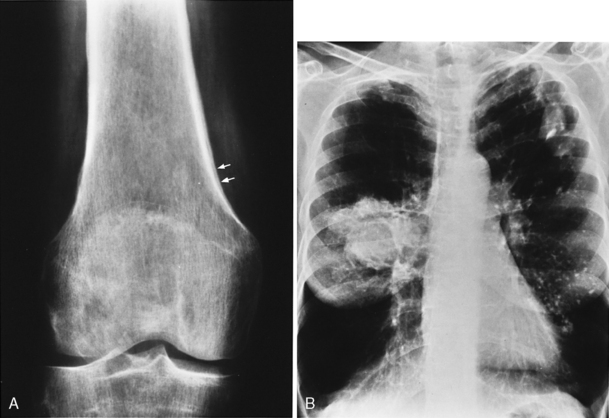

Several paraneoplastic syndromes are associated with lung carcinoma, including clubbing and hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy, which consists of periosteal new bone formation that usually involves the bones of the lower arms and legs (Fig. 11-6). These lesions are usually associated with pain. Other paraneoplastic syndromes include migratory thrombophlebitis and ectopic hormone production, including Cushing’s syndrome from adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) production, hyponatremia associated with inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone (ADH), and hypercalcemia due to excessive parahormone production. There are also a variety of neurologic paraneoplastic syndromes.

Radiologic-Pathologic Correlation

Lung cancer is broadly divided in to small cell lung cancer (SCLC) and non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) based on histologic features and differences in treatment approach. SCLC is considered to be a systemic disease and is treated with a combination of chemotherapy and radiotherapy. NSCLC in the early stages can be treated with surgery. NSCLC is broadly further subclassified as adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and large cell carcinoma (Box 11-7).

Box 11-7 Histologic Classification of Lung Cancer

Modified from the 1999 World Health Organization/International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer Histological Classification of Lung and Pleural Tumours.

Adenocarcinoma

Clinical Features

Adenocarcinoma (Box 11-8) has been increasing in incidence; it is now the most common cell type, accounting for approximately 50% of lung cancer cases. It is the most common cell type in women and in nonsmokers. Because these lesions are typically peripheral in the lung, they may not produce symptoms, and they are found incidentally on a routine chest radiograph.

Bronchioloalveolar Carcinoma

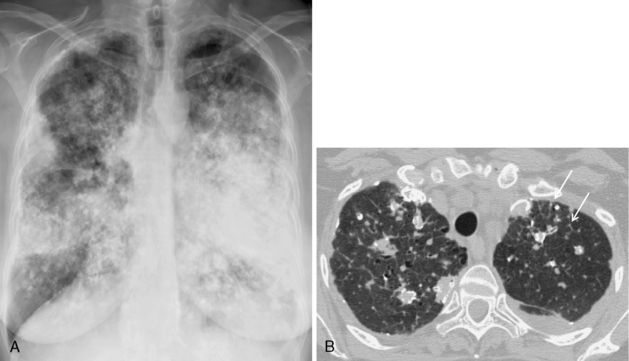

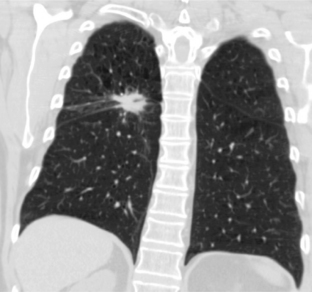

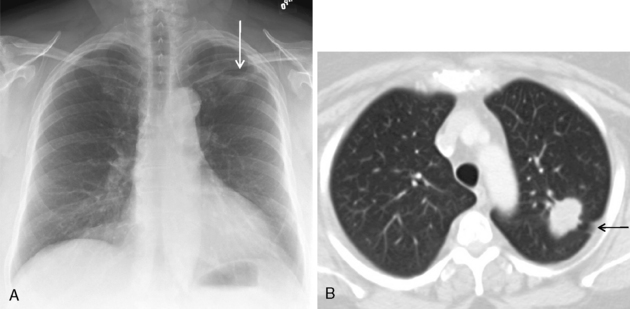

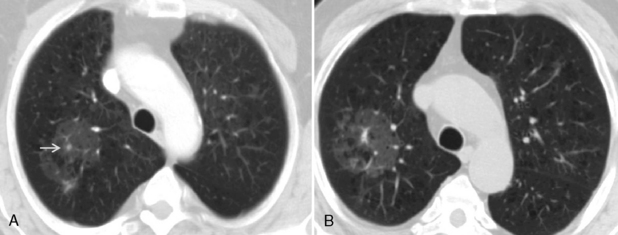

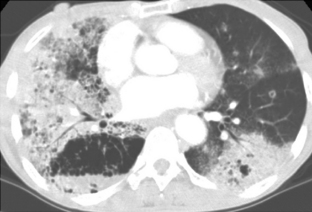

Bronchioloalveolar carcinoma is a subtype of adenocarcinoma. It may manifest with one of three distinct radiologic patterns (Box 11-9). The most common is a solitary nodule. The nodules share the same appearance as adenocarcinoma, although they are often rather hazy and ill defined (Fig. 11-8). They are located peripherally and exhibit lipidic growth, and the growth along the alveolar walls probably accounts for the relatively low density on standard radiographs. On CT, they may exhibit ground-glass opacification, particularly around the periphery of the nodule (see Fig. 11-8). The solitary nodule is associated with an excellent prognosis when it is resected at this stage. An air bronchogram may be identified on standard x-ray films and on CT. The second appearance is that of a pneumonia-like consolidation, which occurs in approximately 20% of cases (Fig. 11-9). This consolidation may be associated with nodules in the same lobe or in other lobes of either lung. This appearance reflects the presumed mode of dissemination of this tumor through the tracheobronchial tree. The third appearance is that of multiple nodules scattered throughout both lungs (Fig. 11-10). These nodules are typically 5 to 6 mm in diameter and tend to have very irregular borders. Very few patients present with this pattern of disease.

Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Clinical Features

Squamous cell carcinoma represents about one third of all lung cancers. It is associated with relatively better prognosis (Box 11-10). Although it grows rapidly, distant metastases occur at a later phase than in adenocarcinoma. There is a strong association with cigarette smoking. Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common cause of Pancoast syndrome, and the cell type is most commonly associated with hypercalcemia due to ectopic parathormone production.

Superior sulcus tumors (i.e., Pancoast tumors) occur at the very apex of the lung in the superior sulcus (Box 11-11). They are typically characterized by pain, Horner’s syndrome, destruction of bone, and atrophy of hand muscles. These tumors typically invade the chest wall and extend into the neck. Local extension may result in involvement of the brachial plexus, spread to the spinal canal and vertebral bodies, involvement of the sympathetic ganglion, and anterior extension with invasion of the subclavian artery. If the local tumor is not extensive, it can be treated successfully with a combination of preoperative irradiation and chemotherapy, followed by lobectomy and chest wall resection.

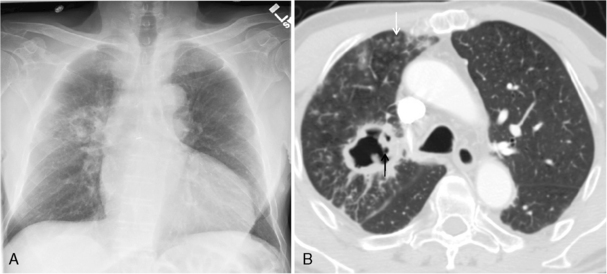

Radiographic Features

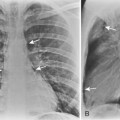

The radiologic presentation depends on the location of the carcinoma. The most common finding is that of a central endobronchial obstructing lesion, which produces a hilar or perihilar mass (Fig. 11-11). Involvement of the central bronchus may range from focal thickening to complete occlusion. When the lesion is small, the tumor may not be evident on the standard radiograph, but the bronchial wall abnormalities are well depicted on CT (Fig. 11-12). Atelectasis or obstructive pneumonitis is usually identified distal to the obstructed bronchus. Any patient presenting with atelectasis and signs of infection should be followed radiographically to complete resolution and reexpansion of the involved lobe. Failure of resolution strongly suggests a central lung carcinoma.

Approximately one third of squamous cell carcinomas occur in the lung periphery. The most characteristic appearance is a thick-walled, cavitary mass that usually does not have an air-fluid level. The diameter ranges from 2 to 10 cm (Fig. 11-13). The cavity may be indistinguishable radiographically from a primary lung abscess. A solitary nodule or mass without cavitation can occur in the periphery of the lung parenchyma.

On standard radiographs, a superior sulcus tumor usually appears as an apical mass or an asymmetric pleural thickening with irregularity that occasionally is associated with rib destruction. Apical thickening alone may be a normal finding; usually, its prevalence is related to age. Much more commonly seen in older individuals, it is usually bilateral, but it may be asymmetric. Any irregular apical thickening that is 5 mm or greater than that on the opposite side should be considered with suspicion. However, most patients with superior sulcus tumors do have clinical symptoms of chest pain. MRI is the preferred modality for evaluating superior sulcus tumors because of its ability to visualize structures at the apex of the thorax in multiple planes. Features of superior sulcus tumors on MRI are discussed later in the section on staging (see “Staging of Lung Cancer”).

Small Cell Lung Carcinoma

Clinical Features

SCLC, the most aggressive form of lung cancer, is characterized by rapid growth and early metastases, which are present in two thirds of patients at the time of presentation (Box 11-12). It is associated with the poorest survival, and it has the strongest and most irrefutable association with cigarette smoking. It accounts for approximately 15% to 20% of all lung cancers. SCLC does not respond to surgical treatment, but it is often managed successfully with chemotherapy. However, long-term survival is extremely poor, and when treated, the median survival is 9 to 18 months. SCLC is staged into two groups: limited-stage disease and extensive disease. Limited-stage disease is limited to one hemithorax with regional nodes, including hilar, ipsilateral, and contralateral mediastinal and supraclavicular nodes. Patients with ipsilateral pleural effusion, irrespective of positive cytology for malignancy, are included under limited-stage disease. Extensive disease typically has extrathoracic disease or thoracic disease that cannot be encompassed in same radiation portal as the primary tumor. Tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) staging is not used, because this system historically relied on surgical confirmation for accuracy, and patients with SCLC are seldom candidates for surgery. However, the SCLC subcommittee of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer (IASLC) recommends that TNM staging be applied in SCLC and that stratification by TNM stage be incorporated into clinical trials. Patients with limited-stage disease (i.e., confined to the thorax) have a 2-year survival rate of approximately 25%.

Box 11-12 Small Cell Lung Carcinoma

ACTH, adrenocorticotropic hormone; ADH, antidiuretic hormone.

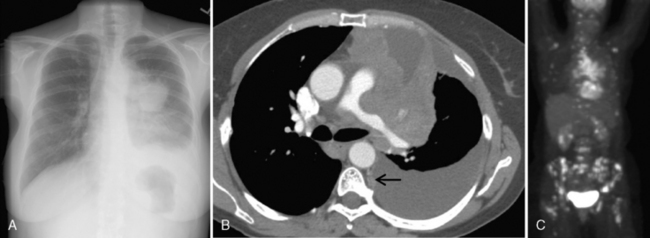

Radiographic Features

The radiographic features usually consist of a hilar or perihilar mass associated with massive, bilateral mediastinal adenopathy (Fig. 11-14). There may be associated lobar collapse. The primary tumor may not be readily evident because it is obscured by the extensive adenopathy. However, CT may show the primary tumor to better advantage. Occasionally, an SCLC manifests as a peripheral nodule that can be resected, and in these relatively uncommon cases, the prognosis is better (Fig 11-15).

Undifferentiated Large Cell Carcinoma

Clinical Features

Large cell carcinomas account for 2% to 5% of lung cancers, and they have a strong association with cigarette smoking (Box 11-13). They are characterized by rapid growth, early metastases, and a poor prognosis.

Staging of Lung Cancer

TNM Classification

The TNM system is widely used to classify lung tumors. In the TNM classification, T indicates the features of the primary tumor, N indicates metastasis to regional lymph nodes, and M refers to the presence or absence of distant metastasis. In 1997, the staging system was revised based on epidemiologic evidence of improved survival after surgical resection in patients who had previously been classified as having unresectable disease. However, these conclusions were derived from analysis of a relatively small database accumulated since 1975. Since then, there have many innovative changes in clinical staging with the routine use of CT and with PET imaging. The IASLC established a lung cancer staging project to analyze a much larger worldwide database of lung cancer. Following this extensive analysis, the Working Committee proposed changes to existing TNM staging system, which will be incorporated in the seventh TNM classification of malignant tumors (Tables 11-1 and 11-2).

Table 11-1 Proposed Definitions for T, N, and M Descriptors

| Stage | Description |

|---|