Fig. 1

49-year-old man with unresectable, liver-dominant intrahepatic ICC. a Axial portal-phase post-contrast CT image demonstrating a heterogeneously hypoenhancing mass centered in segments 7 and 8, measuring up to 9.8 cm. b Segmental right hepatic artery angiography demonstrating tumor blush and discrete neovascularity despite relative hypovascularity by CT. c Follow-up angiography immediately after embolization to segmental vessel stasis with 100 micron Embozene microsphere permanent embolic (CeloNova, Ulm, Germany) demonstrates subtraction artifact from casts of the embolized tumor vessels due to static contrast trapped between microspheres. d Follow-up axial portal-phase post-contrast CT image 2 months after embolization demonstrating decreased enhancement and slight decrease in size from 9.8 to 8.4 cm maximally

There is some evidence that TACE is superior to transarterial chemoinfusion without embolization (TACI) for HCC [13]. More recently, similar data have emerged for the superior efficacy of TACE over TACI in the treatment for ICC as well [14–16]. Results of specific transarterial chemotherapeutic and embolic agents used by different practitioners will be discussed separately in conjunction with individual trials and their results; however, the endpoint of TAE and TACE is generally stasis within the distal small arteries supplying the target tumor(s).

Methodologically, TACE can broadly be divided in two categories: conventional TACE (cTACE) and TACE using drug-eluting bead (DEB-TACE). cTACE uses sterile iodinated poppy seed oil (Lipiodol Ultra-Fluid [previously Ethiodol] Guerbet, Villepinte, France) to create a viscous, radiopaque emulsion with a chemotherapeutic agent or agents that is infused into the tumoral arterial supply. This is usually followed by infusion of temporary or permanent embolic agent, though some practitioners mix the embolic agent with the chemotherapy and Lipiodol and infuse the entire suspension at once. Drug-eDEB-TACE is a modification of TACE in which a single chemotherapeutic agent is bound to the surface of a permanent embolic bead. The beads are mixed suspended in saline and contrast and usually infused without the need for any additional embolic. Once deposited in the tumoral arteries, the chemotherapeutic agent elutes off the beads over a period of several days. Two products are available. LC Beads ([marketed as DC Beads outside the USA], Biocompatibles, BTG, West Conshohocken, USA) are polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) hydrogel microspheres. QuadraSpheres ([HepaSpheres outside the USA], Merit Medical, South Jordan, USA) are hydrophilic microspheres consisting of sodium acrylate alcohol polymer that functions in similar fashion to LC Beads.

TARE, also known as selective internal radiotherapy (SIRT) or radiomicrobrachytherapy (RMB), makes use of neoplastic arterial supply to deposit small glass or starch–resin microspheres within the target tumor(s) that emit beta radiation from directly within the malignancy. Two devices are marked in North America with which to perform TARE. TheraSphere (90Y microspheres; MDS Nordion, Ottawa, ON, Canada) is composed of nonbiodegradable glass microspheres with 90Y as an integral constituent. TheraSphere range from 20 to 30 microns diameter and have a specific gravity of 3.6 g/dL and a specific activity of 2500 Bq/sphere. A 3-GBq vial contains 1.2 × 106 microspheres (TheraSphere package insert, MDS Nordion, Kanata, Canada). They were FDA approved in 1999 with a humanitarian device exemption (HDE) for treatment for unresectable HCC. Approval and oversight by an institutional review board is required to administer TheraSphere. Specific doses may be infused by ordering a predetermined dose-vial and coordinating the day and time of administration with published decay curves. More recently, custom dose vials have allowed greater flexibility in timing of treatment.

SIR-Spheres (Sirtex Medical, Lane Cove, Australia) are resin microspheres onto which 90Y is bound. They range from 20 to 60 microns diameter and have a specific gravity of 1.6 g/dL and a specific activity of 50 Bq/sphere. A 3-GBq vial contains 40–80 × 106 microspheres (SIR-Spheres package insert). SIR-Spheres received premarket FDA approval for treatment for hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer. Their use does not require IRB oversight, but use in any other capacity is off-label. SIR-Spheres arrive in a standard dose vial on the day of treatment. The receiving institution’s radiopharmacist decants an appropriate volume of spheres to achieve the prescribed dose for treatment.

Characteristics of 90Y that facilitates its use in TARE are common to both devices. 90Y is a pure beta emitter that decays to stable 90Zr with a half-life of 64.1 days. The average energy of beta emission is 0.9367 MeV, with a mean and maximum soft tissue penetration of 2.5 and 10 mm, respectively. One GBq (27 mCi) of 90Y per kg of tissue provides a dose of 50 Gy. Doses over 80 Gy are generally considered tumoricidal. TARE takes advantage of the fact that even tumors which appear hypovascular to liver by contrast CT or MRI typically recruit additional arterial supply. There is, therefore, shunting of hepatic arterial flow toward tumors and preferential deposition of radiomicrospheres within the tumors and away from benign liver tissue. Figure 2 depicts treatment of and follow-up imaging for a patient with a partially cystic mixed hepatocellular–intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma.

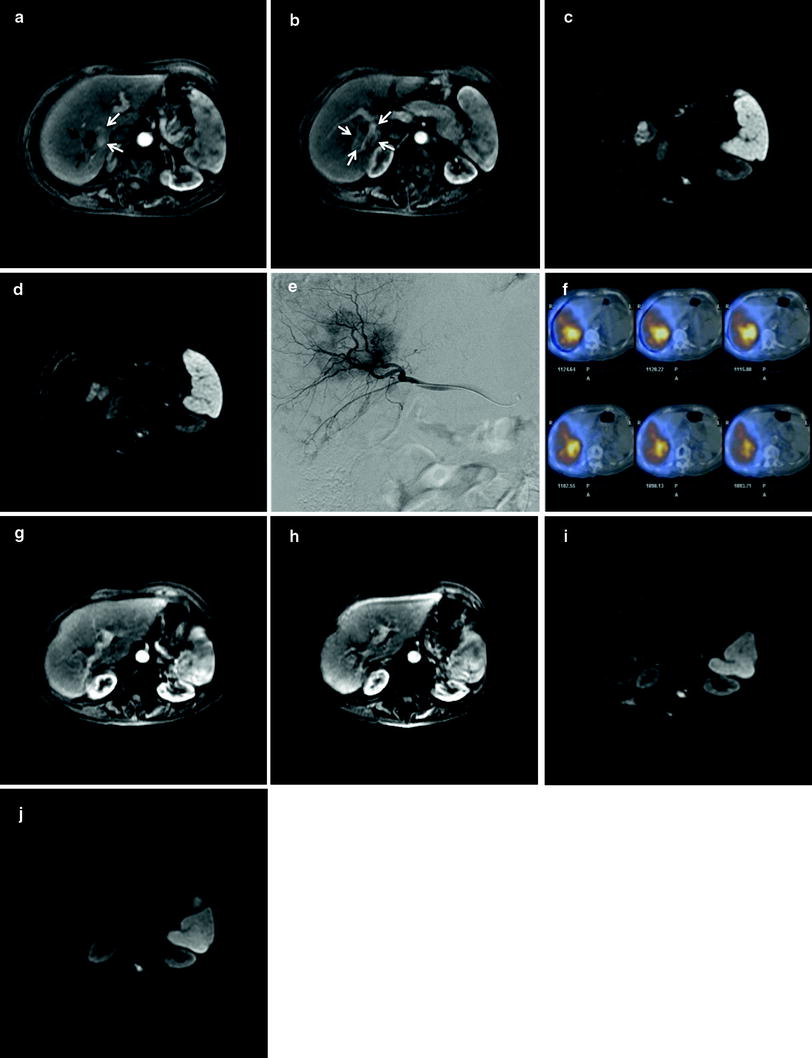

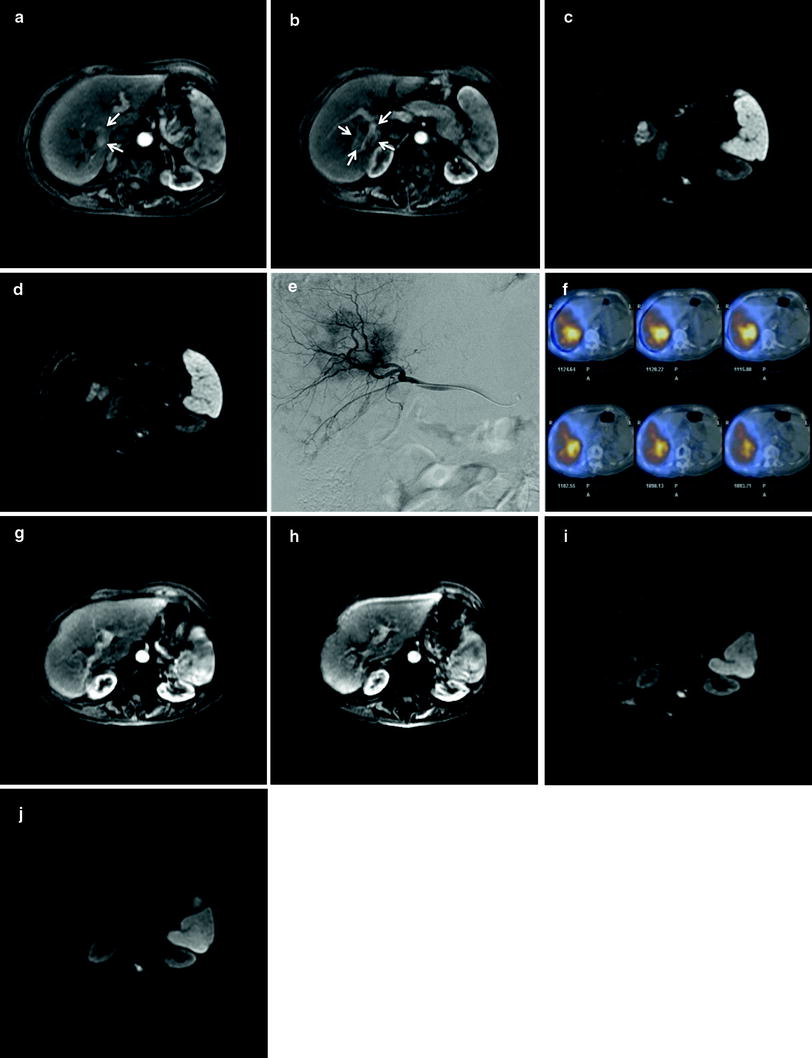

Fig. 2

79-year-old woman with chronic hepatitis B infection and unresectable, biopsy-proven mixed hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma (HCC-ICC) with progression of disease on systemic chemotherapy. a Axial arterial-phase post-contrast MR image demonstrates a mixed cystic (black arrows) and solid (white arrows) lesion on the margin of segments 6 and 7 corresponding to biopsy-proven lesion. b More inferiorly, lesion is more completely solid (white arrows) and surrounds the posterior right portal vein. c pre-TARE diffusion weighted image (DWI) demonstrates markedly restricted diffusion in cystic component of mixed HCC-ICC and moderate to markedly restricted diffusion in the more medial, solid portion of the lesion. d pre-TARE DWI just inferior to prior image shows restricted diffusion corresponding to the HCC-ICC lesion on either side of the posterior right portal vein branch. e Microcatheter angiography performed via the right hepatic artery demonstrates heterogeneous tumor blush corresponding to the known partly cystic segment 6/7 tumor. f Axial fused SPECT-CT images from Bremsstrahlung scan immediately after transarterial radioembolization with a delivered activity of 18.6 mCi (0.69 GBq) of 90Y-resin microspheres infused via the right hepatic artery: white and yellow represent areas of greatest deposition of microspheres, essentially all within the target HCC-ICC, gray is least deposition of microspheres, and light blue is blooming artifact from activity within the right liver. g and h arterial-phase axial images through the superior and inferior aspects of lesion 1 year after TARE demonstrate near complete resolution of enhancement (EASL/mRECIST complete response). i and j superior and inferior DWI 1 year after TARE demonstrates a small focus of restricted diffusion corresponding to residual cystic component of lesion. No restricted diffusion is demonstrated corresponding to any residual solid tumor. Findings in figures g–j are compatible with RECIST partial response and mRECIST/EASL complete response. The patient was alive and asymptomatic at the time of this publication, 12 months after TARE treatment

2.2.3 Post-procedure Care

After transarterial therapy, intravenous hydration, pain control, and anti-emetics are continued as needed. Some authors recommend continuing antibiotic coverage for gram-negative enteric organism in a 3–7 day course, although data for this practice are lacking [17]. A notable exception is patients lacking an intact Sphincter of Oddi. For these patients, continuation of antibiotic prophylaxis for 7-14 days post-embolization has been advocated [18]. Depending on the degree and distribution of embolization, symptoms typical of post-embolization syndrome (i.e., pain, nausea, and fatigue) may require hospitalization for one or more days. In cases of highly selective embolization, patients may often be discharged on the day of treatment after ambulation criteria related to arterial puncture have been met.

2.3 Follow-up

Patients are typically followed with bloodwork and office visits 2 weeks after each treatment, although some practitioners defer office follow-up for 1 month. As described in SIR and CIRSE guidelines, triphasic pre- and post-contrast CT or pre- and dynamic post-contrast MRI should be obtained between 4 and 6 weeks after transarterial therapy and then at 3-month intervals thereafter [4, 5]. Transarterial therapies are typically repeated as warranted by imaging assessment and as long as tolerated by the patient’s clinical and laboratory evidence of functional status.

3 Results

3.1 Conventional TACE and Transarterial Chemoinfusion

Table 1 summarizes results of the TACI and cTACE investigations described here, including also demographic data. Originally described in 1980 for the treatment for HCC, TACE takes advantage of the dual blood supply to benign hepatocytes (from both hepatic artery and portal vein) and the preferential recruitment of arterial neovascularity by HCC tumors to provide more effective treatment for liver tumors with fewer side effects than would be expected from systemic chemotherapy. Shown by two separate randomized, controlled trials in 2002 to improve survival over best supportive care in patients with unresectable HCC, TACE is now considered standard of care for that patient population [10, 11].

Table 1

Results of the TACI and cTACE investigations

Primary author | Year | Study type | Type of treatment | Number of patients | Mean or median # of Rx sessions | Noncirrhotic or CP A | ECOG PS 0 | ECOG PS 1 | ECOG PS 2+ | Prior chemotherapy (%) | Prior external beam radiotherapy (%) | Prior thermal ablation (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Tanaka | 2002 | CS | TACI: fluorouracil ± doxirubicin, epirubicin or mitomycin C | 11 | ||||||||

Burger | 2005 | CS | cTACE: cisplatin, doxorubicin and mitomycin C | 17 | 1.8 | 88 | 12 | 71 | 88 | 35 | 12 | |

Vogl | 2006 | CS | TACI: gemcitabine | 12 | 6 | 25 | 75 | 0 | 100 | 8 | ||

cTACE: gemcitabine + starch microspheres | 12 | 9.2 | 17 | 83 | 0 | 100 | 8 | |||||

Herber | 2007 | CS | cTACE: mitomycin C + Lipiodol | 15 | 3.9 | 93 | 93 | 27 | 7, 7$ | |||

Gusani | 2008 | CS | cTACE: gemcitabine, cisplatin, oxaliplatin or gem-cis combo; all w/TAG microspheres | 42 | 3.5 | |||||||

Kim | 2008 | CS | cisplatin TACI (n = 13) or cisplatin, Lipiodol and gelfoam cTACE (n = 36) | 49 | 3 | 82 | 4$$ | 33$$ | ||||

Park | 2011 | CC | cTACE: cisplatin, Lipiodol and gelfoam | 72 | 2.5 | 65 | 32 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

best supportive care | 83 | 54 | 41 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

Kiefer | 2011 | CS | cTACE: cisplatin, doxorubicin and mitomycin C with PVA spheres | 62 | 2.7 | 89 | 10 | 1 | 29 | 3 | 5 | |

Shen | 2011 | CC | fluorouracil or carboplatin, epirubicin and hydroxycamptothecin TACI ± Lipiodol cTACE | 53 | 60 | |||||||

no transarterial therapy | 72 | 61 | ||||||||||

Vogl | 2012 | CS | cTACE: mito C, gem, mito-gem, or mito-gem-cis, + Lipiodol and starch spheres | 115 | 7.1 | 46 |

Primary author | Prior surgical resection (%) | Mean or median tumor size (cm) | Single tumor (%) | Peripheral morphology (%) | Unilobar disease (%) | Extrahepatic (%) | Portal vein thrombus (%) | Hypervascular tumor (%) | Treatment response imaging criteria | RECIST or WHO imaging assessment of response to treatment at 3 months or earliest post-treatment interval (% CR/PR/(MR)/SD/PD) | Median OS (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Tanaka | 9$ | 6.7 | 55 | 36 | mWHO | 0/45/18(18MR)/18 | 26* ** | ||||

Burger | 12$ | 7.4 | 53 | 36 | 24 | % tumor necrosis | 57 % > 75 % necrosis, 21 % > 25 % necrosis | 23*** | |||

Vogl | 67 | 49 | 67 | WHO | 0/0/75/25 | 13.5* *** # | |||||

50 | WHO | 0/0/92/8 | 20.2* *** # | ||||||||

Herber | 7 | 10.8 | 53 | 40 | 27 | 87 | RECIST | 0/7/60/27 | 16.3 | ||

Gusani | 9.8 | 12 | 45 | RECIST | 0/0/57/43 | 9.1 | |||||

Kim | 8.9 | 29 | 90 | 51 | 73 | RECIST | 0/20/35(tumor necrosis)/31/14 | 10 | |||

Park | 0 | 8.1 | 43 | 49 | 54 | 18## | RECIST | 0/23/67/11 | 12.2 | ||

0 | 7.8 | 53 | 51 | 60 | 12## | 3.3 | |||||

Kiefer | 11 | RECIST | 0/11/64/24 | 15### | |||||||

Shen | 100, 4$ | 63 | 92 | 6 | 12 | ||||||

100, 4$ | 68 | 83 | 10 | 5 | |||||||

Vogl | 30 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 54 | RECIST | 0/9/57/33 | 13 |

Transarterial therapy for ICC was initially reported in 2002 by Tanaka et al. using an implanted subcutaneous port attached to a microcatheter infusing in the common or proper hepatic artery, as had previously been done for HCC. With TACI, no embolic material was administered. Fluorouracil was infused periodically via the port-catheter system with or without doxorubicin, epirubicin, or mitomycin C. Tumor response by follow-up imaging was made using modified WHO criteria: complete response (CR) was disappearance of tumors, partial response (PR) was 50 % or greater reduction in maximum tumor diameter, minor response (MR) was 25–50 % diameter reduction, stable disease (SD) was less than a 25 % change in tumor size, and progressive disease (PD) was 25 % or greater increase in tumor size. Five of 11 patients (45 %) experienced PR, 2/11(18 %) had MR, 2/11 (18 %) had SD, and 2/11 (18 %) had PD. There has been criticism that the authors did not censor one patient downstaged to resection and reported mean survival after treatment initiation of 26.0 months instead of median survival, which would arguably be lower due to the downstaged patient. Nevertheless, the paper by Tanaka et al. proved the principle of transarterial therapy for ICC [19].

The first case series of TACE therapy for unresectable ICC was described by Burger et al. in 2005 in a retrospective report of 17 patients treated with one or more sessions of triple-agent chemotherapy (100 mg cisplatin, 50 mg doxorubicin hydrochloride, and 10 mg mitomycin C) emulsified with Ethiodol and followed by 300–500 micron-diameter tris-acryl gelatin microsphere embolization (Embospheres, Biosphere Medical, Rockland, MA). In keeping with modern TACE technique, the microcatheter used to administer treatment was removed at the end of each treatment session. Three patients could not be followed with MRI. Eight of 14 (57 %) patients who did receive contrast-enhanced MR exams showed >75 % tumor necrosis, and 3/14 (21 %) patients showed 25–50 % necrosis. The authors did not comment on baseline degree of tumor vascularity, and European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) and modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (mRECIST) systems were not explicitly used; however, these results would appear to correlate roughly with between 57 and 78 % complete response rates by these modern criteria. Median survival was 23 months from diagnosis. Two patients were downstaged to resection and were censored from the survival data. The authors did not separately report median survival from time of first TACE treatment [20].

Vogl et. al. recently published a series of 24 patients with either ICC or hepatic metastases of pancreatic adenocarcinoma treated with a dose-escalation protocol using gemcitabine as either TACI or TACE with a mean of 9 treatment sessions. TACE was performed with EmboCept degradable starch microspheres (PharmaCept GmbH, Berlin, Germany). The transarterial catheters were removed after each treatment session. Nine of 12 (75 %) TACI patients and 8/12 (67 %) TACE patients had ICC. In their study, WHO criteria were used to gauge imaging response to treatment. As is often the case after transarterial therapy, there were no complete or partial responses (disappearance of lesions or significant decrease in product of orthogonal tumor diameters, respectively) in either the TACE or TACI group. Nine of 12 (75 %) patients receiving TACI had SD, while 3/12 (25 %) had progression. In the TACE group, there were 11/12 (92 %) with SD and 1/12 (8 %) with progression. The mean time to progression was 4.2 months and 6.8 months in the TACI and TACE groups, respectively (p < 0.01). Mean survival from time of diagnosis was 13.5 months and 20.2 months in the TACI and TACE groups, respectively (p < 0.01) [14].

Herber et al. presented a series of 15 patients with unresectable ICC treated with a mean of 3.9 TACE treatments using mitomycin C in Lipiodol without particle embolization. RECIST criteria were assessed after three treatments: 1 patient had partial response, 9 patients had stable disease, and 5 progressed. Mean and median survival were 21.1 months and 16.3 months after first treatment, respectively. The authors noted mean survival in patients very large or miliary tumors was poorest, 3.4 months, whereas mean survival in patients with focal lesions in a single lobe was 27.5 months [21].

Gusani et al. published a retrospective review of 42 patients with ICC receiving transarterial gemcitabine, cisplatin, oxaliplatin, or gemcitabine with cisplatin, each followed by particle embolization with Embospheres (Biosphere Medical, Inc., Rockland, MA, USA). These investigators showed significantly improved median survival from time of first TACE with gemcitabine–cisplatin dual-agent therapy than with gemcitabine alone (13.8 vs. 6.3 months, p = 0.0005). A median of 3.5 TACE sessions per patient were administered. Twenty of 42 (48 %) patients showing SD by RECIST criteria after 3 treatments were found to have a median survival of 13.1 months, whereas 15/42 (36 %) with PD had a median survival of 6.9 months (p = 0.017). The investigators additionally noted that patients with peripheral tumors treated with TACE had median survival of 18.7 months, while those with central tumors survived a median of 8.2 months after TACE (0 = 0.012). There was no difference seen between patients with and without extrahepatic spread of disease at baseline [22].

Kim et al. published a series of 49 patients receiving either TACE, TACI, or both. Forty of 49 patients (82 %) were Child A, with the remainder being Child B. There were a median of 3 TACE or TACI treatments per patient. Twenty patients received TACE alone, 13 patients received TACI alone, and 16 patients received both TACE and TACI treatments. TACE was performed using cisplatin in Ethiodol followed by 1-mm-diameter gelfoam microsphere embolization of the vessel supplying the tumor. If no tumor hypervascularity was noted at angiography, chemoinfusion was performed without Ethiodol or gelfoam embolic. Median survival from time of first treatment was 10 months. Imaging assessment was performed a month after treatment. RECIST criteria were used with an additional category, tumor necrosis, added by the investigators characterized by lack of tumor enhancement. Ten of 49 patients (20 %) had RECIST PR, 17/49 (35 %) had tumor necrosis, 15/49 (31 %) had SD, and 7/49 (14 %) had PD. The authors defined clinical success as achievement of either RECIST PR or tumor necrosis on imaging follow-up, findings present in a total of 27/49 (55 %) patients. Student’s t and Fischer exact tests were used with uni- and multivariate logistic regression analysis to compare rates of clinical success associated with the following factors: age; sex; child class; tumor size, type (peripheral or periductal-infiltrating), multiplicity and vascularity; prior radiation therapy; treatment group (TACE vs. TACI); and treatment frequency. Two of these variables, treatment modality and tumor vascularity, were found to be significant by univariate regression analysis: 15/20 patients (75 %) receiving TACE had clinical success versus 1/13 (8 %) receiving TACI (p < 0.001), and 26/36 patients (72 %) with hypervascular tumors had clinical success versus 1/13 (8 %) of those with hypovascular tumors (p < 0.001).With multivariate regression analysis, only tumor vascularity was found significantly related to clinical success (OR 31.2, p = 0.002).

Similar analysis was performed assessing these factors’ impact on likelihood of dying during the study period. Tumor hypovascularity (OR = 10.6, p < 0.001), Child-Pugh class B (OR = 4.1, p = 0.006), and treatment with TACI (OR = 4.7, p = 0.002) were associated with decreased survival by univariate analysis. Tumor size of 8 cm or larger approached but did not reach significance (OR = 2.1, p = 0.116). By multivariate analysis, hypovascularity (OR = 13.5, p < 0.001), and Child class B were again associated with decreased likelihood of survival (OR = 3.6, p = 0.014), but treatment group was not found to be significant. Large tumor size, though not found significantly related to survival by univariate analysis, did result in significantly decreased odds of survival by multivariate regression (OR = 2.6, p = 0.048) [15].

Park et al. retrospectively reviewed 155 patients with unresectable ICC, 72 of whom received a mean of 2.5 cTACE treatments and 83 of whom received best supportive care (BSC). TACE was performed as 2 mg/kg cisplatin via the lobar or proper hepatic artery over 15 min, followed by selective embolization of 3–10 mL of 1:1 cisplatin in Ethiodol, followed by embolization to stasis with 1-mm-diameter gelfoam sponge spheres. Overall survival was measured from time of diagnosis in both groups. Log-rank test was used with Student’s t test or the Fischer exact test to identify demographic differences between the cTACE and BSC groups, to detect differential survival between these groups and to perform subgroup analyses of those with liver-only disease, extrahepatic disease, and those showing radiological response to treatment by RECIST criteria versus nonresponders. There were no significant differences between BSC and cTACE groups regarding age; sex; cancer stage; ECOG performance status (PS); tumor location, size, vascularity or multiplicity; or baseline bloodwork including white blood cell count, hemoglobin level, platelet count, serum albumin, total bilirubin, AST, ALT, or ALP (alkaline phosphatase). Median survival from diagnosis was 12.2 months with cTACE versus 3.3 months with BSC (p < 0.001). This difference was upheld in subanalysis of patients with disease confined to the liver (13.3 months with cTACE vs. 4 months with BSC, p < 0.001) and those with extrahepatic spread at baseline (11.3 months with cTACE vs. 3.2 months with BSC, p < 0.001). In those receiving cTACE, survival was longer among those demonstrating objective response (defined by the authors as RECIST PR or CR) than those who displayed none (22 months vs. 10.9 months, p = 0.001). Tumor response to treatment by RECIST criteria from CT scans obtained in 66/72 patients 1–3 months post-cTACE was 15/66 (23 %) PR, 44/66 (67 %) SD, and 7/66 (11 %) PD. ECOG PS; tumor stage, focality, lobar distribution and vascularity; and liver function or other serological characteristics were not found associated with differential survival, possibly, the authors suggested, due to power limitations from small sample size [23].

Kiefer et al. treated 62 patients with biopsy-proven ICC or adenocarcinoma of unknown primary compatible with pancreatobiliary origin thought to represent cholangiocarcinoma at 2 institutions with a mean of 2.7 cTACE sessions using identical TACE technique comprised of 100 mg cisplatin, 10 mg mitomycin C, and 50 mg doxorubicin 1:1 with Ethiodol followed by 0.2 mL of 150–250-micron-diameter spherical PVA particles (Contour SE, Natick, MA). The angiographic goal was stasis in the tumor vessel(s) with forward flow preserved in the infused segmental or lobar artery. Standard pre- and post-procedure medical care was provided. Survival and time to progression (TTP) were calculated for all patients and analyzed by subgroup for differences between pathologic groups. RECIST 1.0 was determined 1 month after completion of TACE. Forty-five of 62 patients had complete imaging follow-up. Five of 45 (11 %) demonstrated PR, 29/45 (64 %) had SD, and 11/45 (24 %) had PD. Three of 29 (10 %) patients with pathology-proven cholangiocarcinoma had PR, 19/29 (66 %) had SD, and 7 (24 %) had PD. In the adenocarcinoma of unknown primary group, there were 2 (13 %) PR, 10 (63 %) SD and 4 (25 %) PD. Median OS in the entire group was 20 and 15 months from time of diagnosis and first TACE, respectively. There was no difference in median survival from diagnosis or first TACE between patients with ICC or adenocarcinoma of unknown primary (20 and 15 months vs. 19 and 14 months, p = 0.88 and 0.51). Prior systemic chemotherapy was associated with prolonged survival (28 vs. 16 months, p = 0.02). The absence of extrahepatic disease trended toward prolonged survival but was not statistically significant (18 vs. 13 months, p = 0.12). Median TTP in any organ was 8 months regardless of the presence or absence of extrahepatic disease. Eighty-two percent of patients had no change in ECOG PS after treatment. The remainder were evenly split between improvement and worsening PS after treatment. Twenty-one patients had abnormally elevated serum CA 19–9 levels at baseline (> 37 U/mL); 4/21 (20 %) normalized after TACE (CR), 8/21 (40 %) declined by 50 % (PR), 7/21 (35 %) changed < 50 % (SD), and 2/21 (10 %) increased > 50 % (PD). A statistical comparison of CA 19–9 levels and survival was not performed. The parity of survival and imaging response to treatment between those with ICC and adenocarcinoma of unknown primary was cited by the authors to support the hypothesis that the two cohorts represent well-differentiated and poorly differentiated ends of a common spectrum of ICC malignancy [24].

Shen et al. published the first dedicated study of adjuvant transarterial therapy after surgical resection with curative intent. In a retrospective series of 125 patients having undergone hepatectomy for ICC, 53/125 (42 %) received TACI or TACE 1.5–2.0 months after resection at the discretion of the surgeon. TACI with fluorouracil 500 mg or a mix of carboplatin 100 mg, epirubicin 20 mg, and hydroxycamptothecin 10 mg was performed via the proper hepatic artery in all patients. For patients with angiographic evidence of recurrent tumor, 3–5 mL of iodinated oil was added to the chemotherapeutic agents. Demographics, OS, and PFS were compared between groups with the chi-squared test. There were no statistically significant differences in these baseline characteristics between those patients receiving transarterial therapy and those who did not. There also were no differences between the two groups regarding age, amount of blood transfused during hepatectomy, adequacy of resection margin, TNM staging, or serum CA 19–9. Demographic variables that did differ between treatment groups were sex and the presence of microvascular invasion. Of those receiving TACE or TACI, only 8/38 (21 %) were women, while 29/72 (40 %) were women in the historical control (p = 0.002). Twenty-three of 53 (43 %) patients treated with TACE/TACI had microvascular invasion, compared to only 15/72 (21 %) of those who did not receive adjunct therapy (p = 0.007). One-, 3-, and 5-year recurrence-free survival periods were not different between the two groups (p = 0.659), but the TACE/TACI group did experience slightly better overall survival (69.8, 37.7 and 28.3 % vs. 54.2, 25.0 and 20.8 %, p = 0.045). Early recurrence was found in 54/125 (43 %) of patients, 27/53 (51 %) of TACE/TACI patients and 27/72 (38 %) of non-TACE/TACI patients. Subgroup analysis showed that median OS in those with early recurrence was 12 months in the TACE/TACI group versus 5 months in the nonadjuvant cohort (p

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree