KEY WORDS

Adenopathy. Enlarged lymph nodes.

Appendicolith (Fecalith). A calculus that may form around fecal material associated with appendicitis. Sonographically appears as an intraluminal echogenic focus with a varying degree of shadowing.

Bacterial Ileocecitis. Infection of the ileum and cecum.

“Bull’s Eye” (Target Sign, Reniform Mass, or Pseudokidney). A characteristic sign of gastrointestinal wall thickening consisting of an echogenic center and a sonolucent rim.

Carcinoid. A yellow, circumscribed tumor occurring in the gastrointestinal tract.

Chronic Intestinal Ischemia. Stenosis or occlusion of the splanchnic (mesentery) arteries. Symptoms may present late in the disease and include upper abdominal pain, which intensifies after a meal and weight loss.

Crohn’s Disease. A recurrent bowel inflammatory disease usually involving the terminal ileum but may affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract. Onset usually occurs between 20 and 40 years of age.

Diverticulitis. Occurs when a herniated outpouching of the intestinal lining becomes inflamed. May perforate and form an abscess.

Fistula. An abnormal communication between the gastrointestinal tract and other internal organs or to the body surface.

Malabsorption Syndrome. Impaired intestinal absorption of nutrients that results in deficiency of vitamins, electrolytes, iron, calcium, etc.

McBurney’s Point. The site of maximum tenderness in the right iliac fossa with appendicitis.

Mesentery. The connective tissue attaching the intestine to the posterior abdominal wall.

Mesoappendix. The layer of connective tissue attaching the appendix to the mesentery of the ileum.

Mesocolon. The layer of connective tissue that attaches the various portions of the colon to the posterior abdominal wall.

Neutropenia. Decreased white blood cell count.

Neutropenic Typhlitis. Inflammation of the cecum that develops in the setting of severe neutropenia when a patient is immunosuppressed.

Peritonitis. Infection of the abdomen’s inner lining.

Rebound Tenderness. Most severe abdominal discomfort when pressure is released quickly rather than when the abdomen is compressed.

Septicemia. Infection involving the bloodstream.

Vasodilation. Increased blood flow in an inflamed organ and the surrounding tissues. Associated with increased heat and redness.

The Clinical Problem

A number of entities can cause right iliac fossa pain—notably appendicitis. The pathology may be linked to the bowel found in this location (i.e., cecum, terminal ileum, and appendix) or the adjacent organs (i.e., right kidney, right ureter, bladder, ovary, uterus, or gallbladder) (see Fig. 15-3). A rapid and accurate diagnosis can be critical for a patient with acute abdominal pain. Ultrasound is a helpful tool to lead the physician to the correct diagnosis.

Not all intestinal problems require surgery. In approximately 25% of appendectomies, a misdiagnosis of appendicitis results in the removal of a normal appendix and a delay of appropriate treatment for the patient. Some conditions, such as bacterial ileocecitis, call for nonsurgical treatments. A thorough history followed by a targeted sonogram will spare the patient unnecessary procedures and point to the proper treatment.

APPENDICITIS

Although appendicitis is most common in children and young adults, it can occur at any age with a lifetime risk of 7%. The cause of appendicitis is obstruction of the appendix followed by infection. If the obstruction is not relieved spontaneously, inflammation and increased intraluminal pressure cause midabdominal pain, which later localizes over the appendix. When surgical intervention is delayed, bacteria may invade the appendiceal wall, and perforation may occur.

At this stage, the patient’s life is in danger. When the appendix perforates into the abdominal cavity, peritonitis occurs, followed by abscess formation, and occasionally death.

In most cases, the spread of infection after perforation is contained by mesentery and intestine in the appendix region. This collection is called an appendical phlegmon or an appendical abscess if there is pus within. Although an appendical phlegmon may resolve and reabsorb on its own, further infections may follow with the development of fistulous tracts to surrounding bowel, the bladder, the skin, or the vagina. If the infection becomes more widespread, death may result from septicemia or peritonitis.

Patients with classic symptoms of appendicitis may be sent straight to surgery. Atypical cases may be referred to ultrasound to rule out pelvic, renal, or gallbladder pathology. A prompt diagnosis is required to avoid perforation of the appendix.

The presenting symptoms include one or more of the following features:

1. Pain that starts in the periumbilical region, then localizes to the right lower quadrant (McBurney’s point)

2. Rebound tenderness (tenderness that is most severe when pressure is released)

3. Poor appetite, nausea, vomiting, and/or diarrhea

4. Fever

5. Leukocytosis—white blood cell count of 10,000 to 18,000/mL

BACTERIAL ILEOCECITIS

Bacterial ileocecitis is inflammation of the terminal ileum, cecum, and surrounding nodes caused by a bacterial infection. The most common culprits are Yersinia enterocolitica, Campylobacter jejuni, Salmonella enteritidis, and rarely Y. pseudotuberculosis and Salmonella Typhi. In this condition, the appendix may be affected, but is not obstructed. Therefore, perforation is not a threat, and surgery is not indicated.

Bacterial ileocecitis is often confused with acute appendicitis. A meal containing chicken in the patient’s history may be a clue. Diarrhea may be present and can be bloody.

CROHN’S DISEASE

The cause of this inflammatory process of the gastrointestinal tract is yet unknown. Most patients with Crohn’s are young adults. Although this disease may affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract, the terminal ileum is the most common site. The undiagnosed patient may present with the following:

1. A painful mass in the right iliac fossa

2. Crampy abdominal pain

3. Intermittent diarrhea

4. Weakness, fever, increased white blood cell count, weight loss, or malabsorption syndrome

Patients with Crohn’s disease are occasionally followed with ultrasound during therapy to monitor bowel wall thickness or abscesses.

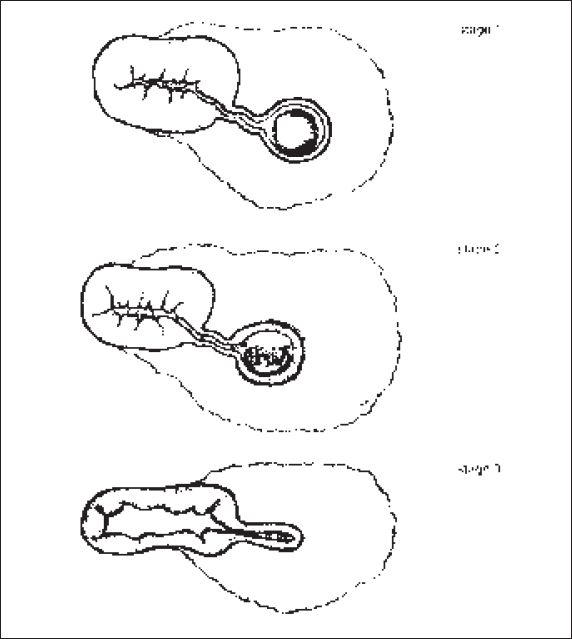

Clinically similar to appendicitis, although usually on the left, diverticulitis is not often life-threatening. It involves herniated outpouches of large bowel wall and diverticula that become infected and inflamed. Similar to appendicitis, the neck of the diverticulum becomes obstructed and infection accumulates within the diverticulum (Fig. 15-1, stage 1). Usually, the pressure builds until the pus is released into the bowel lumen (Fig. 15-1, stage 2). Despite the abscess, the bowel often functions normally (Fig. 15-1, stage 3). Although not common, perforation may occur followed by fecal peritonitis.

Sigmoid diverticulitis is the most common cause of acute left lower quadrant pain and is referred to as left-sided appendicitis. Cecal diverticulitis can be clinically indiscernible from appendicitis.

MESENTERIC ADENITIS

Mesenteric adenitis is often the cause of enlarged mesenteric nodes. It is seen mostly in young children. Presenting symptoms are a painful right lower quadrant mass and possibly positive stool cultures.

INTUSSUSCEPTION

Patients with intussusception are usually children (see Chapter 35, Pediatric Abdominal Masses). Most children present with a painful abdominal mass, often with vomiting or bloody-mucous diarrhea.

NEUTROPENIC TYPHLITIS

Neutropenic typhlitis occurs in immunosuppressed patients. Symptoms include severe neutropenia and right lower quadrant pain. Fever, nausea, vomiting, and bloody diarrhea may also be present.

INTESTINAL TUMORS

Intestinal tumors may be seen at any age. Colorectal cancer is the second most frequent cause of cancer-related death in the United States. Lymphoma is a disease of young adults. Leiomyosarcoma occurs in the fifth to sixth decades, and most carcinomas are seen in older patients. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor is a newly described malignancy of the gastrointestinal tract that is similar to leiomyomas and leiomyosarcomas. The clinical signs from any of these entities may include a painful abdominal mass, bloody stool, anorexia, diarrhea, constipation, and weight loss.

Figure 15-1. ![]() Illustration demonstrating the stages diverticulitis may follow. (Adapted and reprinted from Puylaert JB. Acute appendicitis: ultrasound evaluation using graded compression. Radiology 1986;158:355–360, with permission.)

Illustration demonstrating the stages diverticulitis may follow. (Adapted and reprinted from Puylaert JB. Acute appendicitis: ultrasound evaluation using graded compression. Radiology 1986;158:355–360, with permission.)

Anatomy

MUSCLE

With high-resolution sonography, the oblique muscles, rectus, and psoas muscles can be visualized in most individuals (Fig. 15-2). These muscles can be the site of abscesses or mistaken for an abdominal mass.

INTESTINE

The bowel encountered in the right lower quadrant may include the ascending colon, cecum, appendix, and terminal ileum (Fig. 15-3). With the proper technique, the ascending colon and cecum are usually visualized filled with echogenic bowel gas, feces, or hypoechoic fluid. By following the cecum caudally and medially, the terminal ileum may be seen entering the large bowel with active peristalsis. A normal appendix is rarely identified extending from the cecum. The normal appendix has a diameter of less than 6 mm.

Histologically, the gastrointestinal wall may be divided into five layers. From the lumen out, they are the mucosa, muscularis mucosa, submucosa, muscularis propria, and serosa or fat surrounding the outside of bowel (Fig. 15-4

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree