Case presentation

A 3-week-old male presents with nonbilious, nonbloody emesis for the past 1.5 weeks. Initially there were two to three episodes per day, occasionally with feeding, but this has increased to emesis with every feed. The parents report that the emesis is “forceful” and afterward the child appears to want to eat again. He has had decreased urine output over the past 24 hours. There has been no fever, diarrhea, or known trauma. He has been increasingly fussy for the past several days. He has an unremarkable medical history and was born “full term.”

Physical examination reveals an afebrile child with a heart rate of 130 beats per minute, respiratory rate of 40 breaths per minute, and a blood pressure of 84/60 mm Hg. The baby is fussy but consoles as he eagerly takes a pacifier. Mucous membranes are slightly dry, but the physical examination is otherwise normal

Imaging considerations

Plain radiography

Plain abdominal radiography is not particularly useful for the diagnosis of pyloric stenosis. However, if obtained, gastric distention may be seen or perhaps mass impression of the thickened pyloric muscle on an air-filled gastric antrum may be noted. ,

Ultrasound (US)

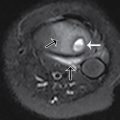

US is the imaging modality of choice in children with suspected pyloric stenosis. This modality is readily available and there is no exposure to ionizing radiation. Criteria that suggest the diagnosis of pyloric stenosis in full-term infants are as follows :

- 1.

Muscle thickness greater than 3 mm.

- 2.

Channel length greater than 16–18 mm.

US has a diagnostic sensitivity and specificity of 89% and 100%, respectively. The passage of gastric contents in real time can help aid with the diagnosis of pyloric stenosis in this group. An interesting phenomenon is that of pylorospasm, a common cause of gastric outlet obstruction in neonates; this is managed conservatively, but close follow-up is indicated. , , Infants with equivocal results should be followed closely as well, with repeat imaging as clinically indicated.

Upper gastrointestinal series (UGI)

This modality was traditionally used to diagnose pyloric stenosis and has the ability to detect other conditions that may mimic pyloric stenosis, such as gastroesophageal reflux. , A UGI has a sensitivity and specificity for pyloric stenosis reported to be 96% and 100%, respectively. This test does require expertise in the technique of administering oral contrast and interpreting the results. UGI series includes exposure to ionizing radiation, and this exposure can be increased due to increased fluoroscopic observation times necessitated by the delay in gastric emptying in patients with pyloric stenosis.

Computed tomography (CT)

Computed tomography of the abdomen is not indicated to diagnose pyloric stenosis.

Imaging findings

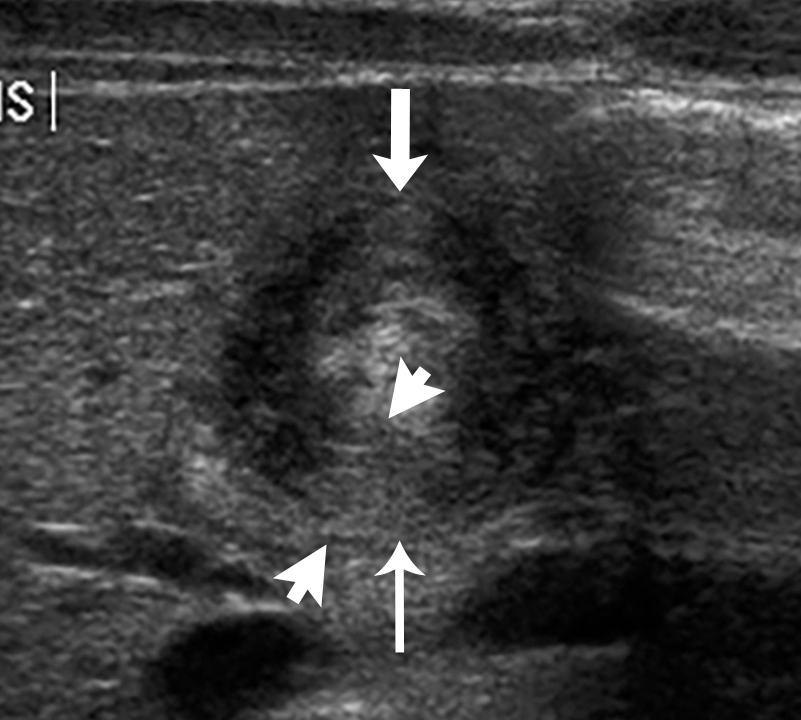

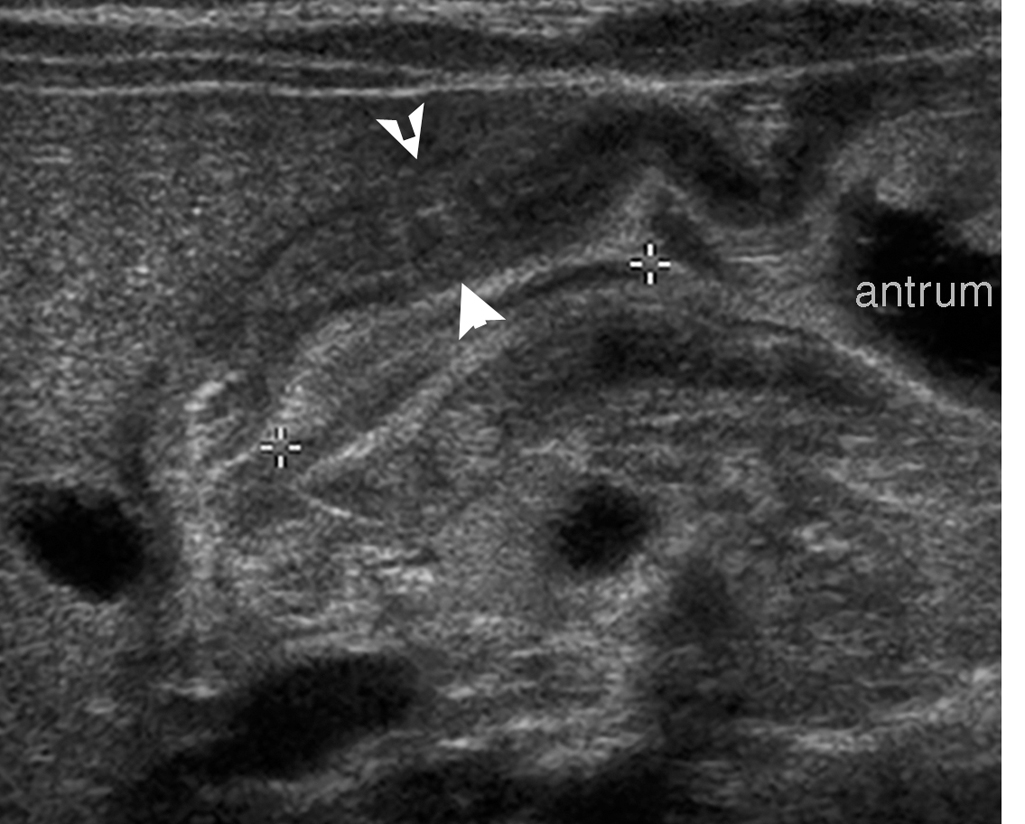

Given the history and physical examination, an abdominal US was obtained. There is abnormal circumferential muscular wall thickening of the antropyloric region, with a single-wall thickness of 4.4 mm, a channel length of 19 mm, with mass effect upon the gastric antrum and duodenum bulb ( Figs. 20.1 and 20.2 ).