SONOGRAM ABBREVIATIONS

Ao Aorta

CBD Common bile duct

GB, Gbl Gallbladder

IVC Inferior vena cava

K Kidney

L Liver

Pv Portal vein

S Spine

KEY WORDS

Acute Abdomen. Sudden onset of abdominal pain. Causes include appendicitis, perforated peptic ulcer, strangulated hernia, acute cholecystitis, pancreatitis, and renal colic.

Adenomyomatosis. A chronic gallbladder condition causing right upper quadrant (RUQ) pain with several sonographic manifestations—the most common are multiple, small polypoid masses arising from the gallbladder wall.

AIDS. Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (see Chapter 11).

Amebiasis. Infection with amebic parasite, common in Mexico, the southern United States, and warm climates.

Ameboma of the Liver. Abscess caused by amebiasis.

Cholangitis. Inflammation of a bile duct.

Cholecystitis. Inflammation of the gallbladder.

Acute. Usually caused by gallbladder outlet obstruction.

Chronic. Inflammation persisting over a longer period.

Choledochojejunostomy. Surgical procedure in which the bile duct is anastomosed to jejunum; food and air may reflux into the bile ducts.

Choledocholithiasis. Gallstone in a bile duct.

Cholelithiasis. Gallstones in the gallbladder.

Cholesterosis (Cholesterolosis). Variant of adenomyomatosis in which cholesterol polyps arise from the gallbladder wall.

Hartmann’s Pouch. Portion of the gallbladder that lies nearest the cystic duct where stones often collect.

Junctional Fold. Septum usually arising from the posterior midaspect of the gallbladder, a normal variant.

Murphy’s Sign. Tenderness when an inflamed gallbladder is palpated clinically, usually on deep inspiration.

Phrygian Cap. Variant gallbladder shape in which the gallbladder’s fundus is separated from the body of the gallbladder by a junctional fold.

Pyogenic. Producing pus.

Rokitansky-Aschoff Sinuses (RAS). Multiple pouches in the wall of the gallbladder, which often fill with cholesterol crystals.

Sphincterotomy. Procedure in which the sphincter of Oddi is widened surgically. Gas will reflux into the bile ducts.

Wall Echo Shadow (WES), Wall Echo Shadow Complex (WESC), or Double Arc Shadow Sign. Sonographic pattern seen when the gallbladder is filled with stones. The WES consists of two curved, parallel bright lines separated by a thin, anechoic space, accompanied by posterior acoustic shadowing.

RELEVANT LABORATORY VALUES*

Alkaline phosphatase: 40 to 135 U/L

ALT (SGPT): 5 to 60 U/L

AST (SGOT): 5 to 42 U/L

Bilirubin

Direct: 0.0 to 0.3 mg/dL

Total: 0.1 to 1.6 mg/dL

GGT: 1 to 50 U/L

White blood cell count: 3,800 to 10,500/uL

*See Chapter 10 for definitions. Numbers listed for each measurement are the range of normal values.

The Clinical Problem

RUQ pain, either chronic or acute, may be caused by disease in the gallbladder, liver, porta hepatis, pancreas, right kidney, adrenal gland, lung, or diaphragmatic pleura. Differential diagnosis is sometimes difficult and often requires the use of many modalities, including the patient’s history and physical examination, laboratory tests, computed tomography (CT) scans, nuclear medicine, magnetic resonance imaging, and ultrasound. Important physical signs and symptoms include the presence or absence of jaundice, acute pain, fever, and vomiting.

Ruling out gallstones is perhaps the most common indication for an RUQ scan. Although stones in the gallbladder and ducts certainly can cause pain, they are often asymptomatic. Because choledocholithiasis may be indicated by increases in liver function tests before any pain is experienced, this condition will be discussed in Chapter 10. The clinician asks for concrete evidence from the sonographer before referring the patient to a surgeon: Does the gallbladder have stones? A thickened wall? Fluid around it? Is it locally tender? Is it enlarged? Is there biliary tree dilatation? Is there any evidence of a gallbladder tumor?

When RUQ pain is acute, rapid and accurate diagnosis on an emergency basis may be crucial. Many of the internal disasters that precipitate an acute abdomen, such as renal colic with secondary hydronephrosis, and pancreatitis, are readily detectable with ultrasound. Others, however, such as perforated ulcer, are not. Due to the proximity of the gallbladder and pancreas to the right hemidiaphragm, patients with cholecystitis and pancreatitis sometimes experience referred pain in the right shoulder area. Pain may also be referred into the RUQ from inflammation of the diaphragmatic pleura. Thus, the sonographic finding of an unsuspected pleural effusion may shift the focus of the work-up to the chest. Pyelonephritis and renal stones (see Chapter 20), as well as liver tumor or abscess, may present as RUQ pain.

Sometimes, RUQ pain is the result of chronic disease, as when oncology patients have viscous bile from prolonged stasis and develop acute acalculous cholecystitis or gallstones, or when AIDS patients develop cholangitis. RUQ abnormalities may be incidental findings in these patients because the pain may not be marked, or because the signs and symptoms wind up buried in a very complex clinical picture. These patients require a careful search for any problem that can be treated to alleviate pain.

Anatomy

GALLBLADDER

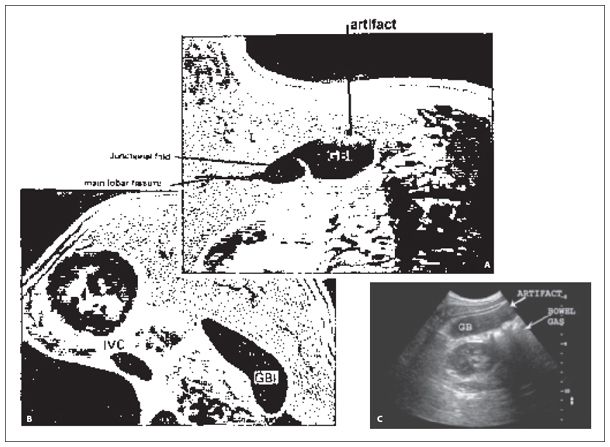

The gallbladder is situated on the inferior aspect of the liver, medial and anterior to the kidney, and lateral and anterior to the inferior vena cava. The main lobar fissure is a sonographic landmark leading to the gallbladder fossa, seen as an echogenic line (Fig. 9-1) that runs from the right portal vein to the gallbladder. The gallbladder is pear-shaped and varies in size. It may contain a kink (the junctional fold) close to the neck (Fig. 9-2). It is divided into the fundus (the distal tip area), the body, and the neck (Hartmann’s pouch is that portion of the gallbladder between the junctional fold and the neck). The gallbladder has an echogenic wall that should not be more than 3 mm thick in a fasting patient. See Chapter 10, Abnormal Liver Function Tests: Jaundice, for anatomy of the biliary tree.

Figure 9-1. ![]() Diagram showing the main lobar fissure between the right portal vein and the gallbladder. Note the refractive acoustic shadowing from the gallbladder wall and the portal vein wall. There is no echo source for these areas as there would be if a gallstone were present.

Diagram showing the main lobar fissure between the right portal vein and the gallbladder. Note the refractive acoustic shadowing from the gallbladder wall and the portal vein wall. There is no echo source for these areas as there would be if a gallstone were present.

Figure 9-2. ![]() Reverberation artifacts. A. Reverberations are a common problem in the anterior aspect of the gallbladder (artifact). The gallbladder is easily located by following the main lobar fissure from the right portal vein to the gallbladder fossa. The fold at the neck of the gallbladder could cause confusion if caught in a plane that demonstrated only a portion of it. B. Increasing the gallbladder’s distance from the transducer by turning the patient in a decubitus position moves the gallbladder wall into the focal zone of the transducer and decreases reverberations. The decubitus position allows the fundus to fall and the kink to straighten out. C. In this grayscale image showing reverberation artifact filling gallbladder lumen with false echoes, note the nearby bowel forming a “dirty” shadow.

Reverberation artifacts. A. Reverberations are a common problem in the anterior aspect of the gallbladder (artifact). The gallbladder is easily located by following the main lobar fissure from the right portal vein to the gallbladder fossa. The fold at the neck of the gallbladder could cause confusion if caught in a plane that demonstrated only a portion of it. B. Increasing the gallbladder’s distance from the transducer by turning the patient in a decubitus position moves the gallbladder wall into the focal zone of the transducer and decreases reverberations. The decubitus position allows the fundus to fall and the kink to straighten out. C. In this grayscale image showing reverberation artifact filling gallbladder lumen with false echoes, note the nearby bowel forming a “dirty” shadow.

Technique

PATIENT PREPARATION

Gallbladder studies should be performed after an overnight fast of 8 to 12 hours. Water (and oral contrast for CT, which has only a weak contracting effect on the gallbladder) is permitted, but be sure the patient is not scheduled for other exams for which he or she should be without fluids, such as an upper gastrointestinal series.

Even if the gallbladder is not present, abdominal sonograms benefit from the patient’s fasting; there is less air in the stomach, and it makes a better window if there is a need to fill it with water.

TRANSDUCER

The two most important points to remember in scanning gallbladders are to use a transducer with a high frequency and to set the focal zone at the back wall where stones collect. The frequency must be adequate to penetrate the entire organ, but you may need to change the transducer from the one used to demonstrate the right lobe of the liver, or you can obliterate subtle shadowing. Tissue harmonic imaging clears artifact within the gallbladder lumen and may enhance the presence of posterior acoustic shadowing in smaller stones. If using a system with spatial compounding, consider turning off compounding while looking for shadows, as compounding may obscure subtle shadows. A high-frequency linear transducer can be used when the gallbladder is located close to the abdominal wall to aid in accurate wall measurements and to enhance shadowing in very small stones.

Supine Position

The gallbladder is first examined with the patient in a supine position using a sector or curvilinear scanner (a linear probe may be used to show Rokitansky-Aschoff sinuses and to obtain more accurate gallbladder wall measurements). Try to obtain long-axis views by varying the obliquity of the transducer until the maximum length of the gallbladder is seen. Scan through the short axis of the gallbladder, beginning at the neck and sweeping through the fundus. It is often necessary to angle caudally through the body to demonstrate the entire fundus well, as it can be tucked up under the bowel. To view the gallbladder, it may be helpful to scan through an intercostal space with the right arm raised above the head (if possible), or to scan from a subcostal approach with breathhold on inspiration.

Decubitus Position

It is mandatory to obtain additional gallbladder views in the left lateral decubitus (right side up), oblique, prone, or upright position because stones may be missed if only supine views are obtained (Fig. 9-2). They might be small and therefore undetectable along the back wall. Changing position can pile stones together and can create enough volume to produce shadowing. The decubitus position allows the liver to act as an acoustic window for visualizing the gallbladder. Stones and gravel will fall into the most dependent portion—usually the fundus—whereas polyps or adherent stones will stay put. Sludge will only gradually level off in the bottom. Think of sludge movement as similar to that of molasses or honey—it may take some time to shift noticeably after a change in position.

Prone Position

If the most dependent part of the gallbladder becomes obscured by bowel on a decubitus view, or if there are no stones seen on supine and decubitus views, persist and try a prone view. Position the transducer on the patient’s side and scan coronally through the liver when the patient is in a decubitus position, then watch while the patient rolls flat (or flatter) onto the stomach. It’s important not to let the patient get settled in the prone position before visualizing the gallbladder, because the advantage of this position is in seeing the “snowflakes” falling as the patient turns. Sometimes prone positioning picks up stones that layered and were undetectable on other views.

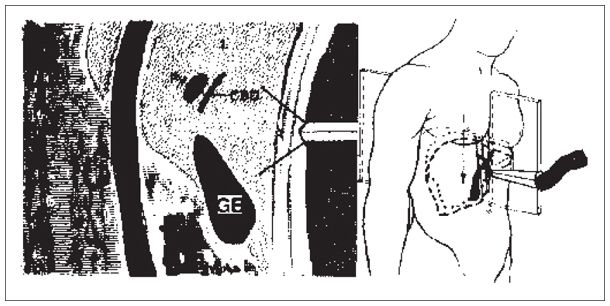

Upright Position

The upright position is awkward for both patient and sonographer, but in patients with a small, high liver and large anteroposterior diameter, it may be the best alternate view. Don’t just sit the patient up on the stretcher, as the bowel may push up in front of the gallbladder (Fig. 9-3). Have the patient stand and brace against the stretcher. Don’t waste all this effort—be sure to scan the pancreas while the patient is upright. In patients with this build, it’s often the best way to get an acoustic window, and so it is worth the trouble.

Figure 9-3

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree