TABLE 5.1 Small Round Cell Tumors of Bone | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Monostotic or polyostotic histiocytic and dendritic monoclonal cell disorder characterized by neoplastic proliferation of Langerhans cells that normally populate the skin, mucosal surfaces, lymph nodes, and other tissues

Relatively rare disorder, accounting for less than 1% of all osseous lesions.

Age distribution ranging from the first month of life to eighth decade, with 80% to 85% of cases seen in patients under the age of 30, and 60% under the age of 10.

Males are affected twice as often as females.

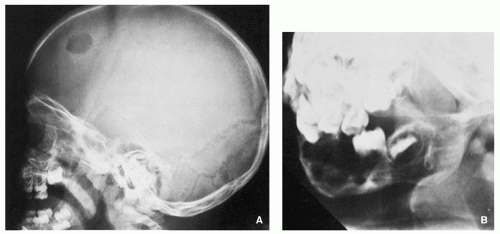

Any bone may be affected, although there is predilection to involve the bones of the skull, particularly the calvaria.

Other commonly involved sites include the femur, the bones of the pelvis, ribs, vertebrae, and the mandible.

Pain and swelling of the affected area occur most commonly.

In cases of temporal bone involvement, the presenting features can overlap with those of otitis media and mastoiditis.

Mandibular involvement may result in loosening and loss of teeth.

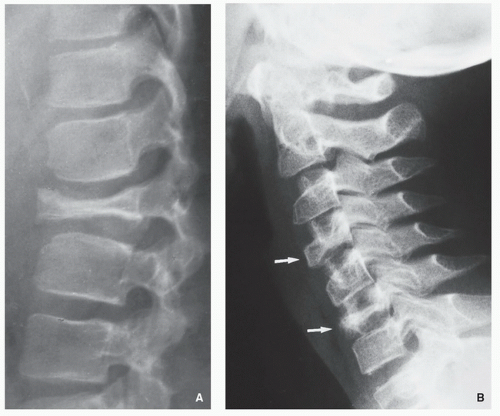

Involvement of vertebral body may result in compression fracture and possible neurologic impairment.

Fever, elevated sedimentation rate, and leukocytosis may be present.

TABLE 5.2 Small Round Cell Tumors of Bone and Typical Immunohistochemistry Results

Tumor

bcl-2

CK

Vim

Des

NF

CD99

CD57

NSE

CD45

Light Chains κ or λ

Syn

CD138

Ewing sarcoma

–

+/a

+

–

-/a

+

(+)

–

–

–

–

–

PNET/Askin tumor

–

–

+

–

(+)

+

(+)

+

–

–

+

–

Malignant lymphoma

+

–

+

–

–

(+)

(+)

–

+

+/-

–

(+)

Myeloma

+

–

-/+

–

–

(+)

–

–

-/+

+

–

+

Small cell osteosarcoma

–

–

+

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

Mesenchymal chondrosarcoma

–

–

+

–

–

+

–

–

–

–

–

–

Metastatic neuroblastoma

–

–

–

–

+

–

(+)

+

–

–

+

–

Rhabdomyosarcoma

–

–

(+)

+

–

–

–

(+)

–

–

–

–

Synovial sarcoma

+

+

+

–

–

+

–

–

–

–

–

(+)

Desmoplastic small round cell tumor

–

+

+

+

–

(+)

+

+

–

–

+

–

From Greenspan A, Jundt G, Remagen W. Differential Diagnosis in Orthopaedic Oncology. 2nd ed. p. 333 , Table 5-2.

TABLE 5.3 Revised European-American Lymphoma Classification

B-Cell Lymphomas

T-Cell and Natural Killer Cell Neoplasms

Hodgkin Disease

Precursor B-cell neoplasm

▪ Precursor B-lymphoblastic leukemia or lymphoma

Mature B-cell neoplasm

▪ B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia, prolymphocytic leukemia, small lymphocytic leukemia

▪ Lymphoplasmacytoid lymphoma

▪ Mantle cell lymphoma

▪ Follicle center lymphoma

▪ Marginal zone B-cell lymphoma

▪ Hairy cell lymphoma

▪ Diffuse large cell B-cell lymphoma

▪ Burkitt lymphoma

▪ High-grade B-cell lymphoma

Precursor T-cell neoplasm

▪ Precursor T-lymphoblastic lymphoma or leukemia

Peripheral T-cell and natural killer cell neoplasm

▪ T-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia

▪ Large granular lymphocyte leukemia

▪ Mycosis fungoides, Sézary syndrome

▪ Peripheral T-cell lymphoma

▪ Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma

▪ Angiocentric lymphoma

▪ Adult T-cell lymphoma

▪ Anaplastic large cell lymphoma

Nodular lymphocyte predominance (paragranuloma)

Nodular sclerosis

Mixed cellularity

Lymphocyte depletion

Lymphocyte-rich classic Hodgkin disease

From Greenspan A, Jundt G, Remagen W. Differential Diagnosis in Orthopaedic Oncology. 2nd ed. p. 335 , Table 5-3. Modified from Krishnan A, Shirkhoda A, Tehranzadeh J, et al. Primary bone lymphoma: radiographic—MR imaging correlation. Radiographics. 2003;23:1371-1387, with permission.

Single or multiple lesions restricted to the skeleton have been termed eosinophilic granuloma.

Multifocal bone disease associated with exophthalmos and diabetes insipidus is known as Hand-Schuller-Christian disease.

Letterer-Siwe disease (nonlipid reticulosis) is a condition that usually affects very young children (<2 years old) and consists of disseminated bone lesions, anemia, lymphadenopathy, and splenomegaly.

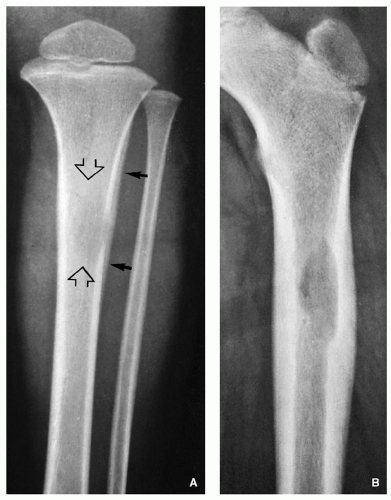

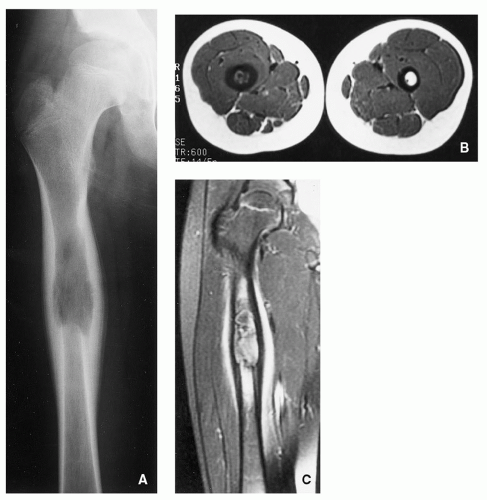

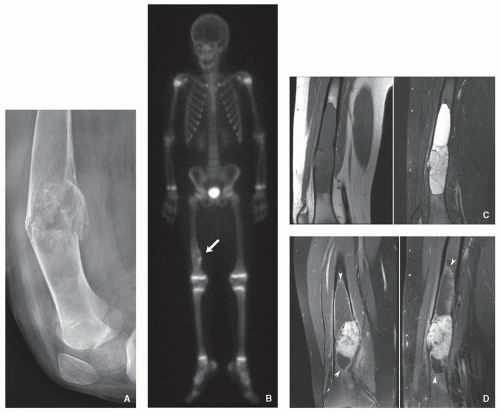

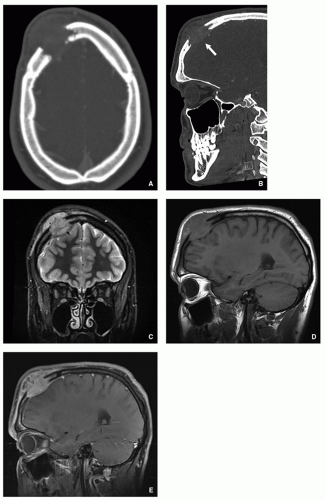

Radiography shows well-defined, lytic lesions; however, in a minority of cases, the lesions may exhibit wide zone of transition and permeative type of bone destruction (Figs. 5.1, 5.2 and 5.3). More sclerotic appearance is seen in later stages of the disease (Fig. 5.4). Some lesions may show slanting or beveling of the edges. Scalloping of the endocortex is a common finding (see Fig. 5.1B).

Cortical involvement may elicit an aggressive lamellated (onion-skin) type of periosteal reaction (Fig. 5.5A, see also Fig. 5.1A).

Scintigraphy generally shows increased uptake of the radiopharmaceutical tracer (see Fig. 5.6B), but about 35% of lesions show normal radionuclide bone scan.

Involved tissue is soft and red in color.

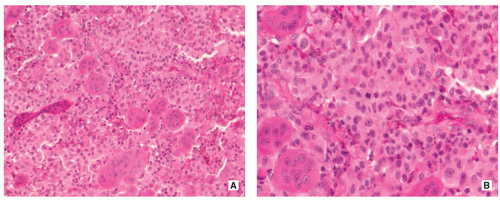

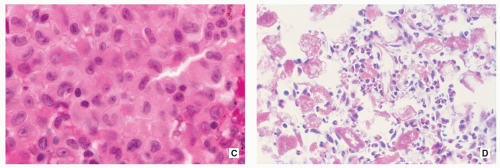

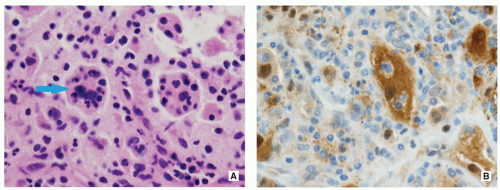

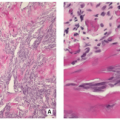

Proliferating Langerhans cells are arranged in aggregates, sheets, or individually within a loose fibrous stroma, exhibiting indistinct cytoplasmic borders and eosinophilic to clear cytoplasm (Fig. 5.9).

The nuclei are translucent, ovoid, coffee bean or kidney shaped with typical longitudinal grooves (Fig. 5.9C).

Chromatin is either diffusely dispersed or condensed along the nuclear membranes.

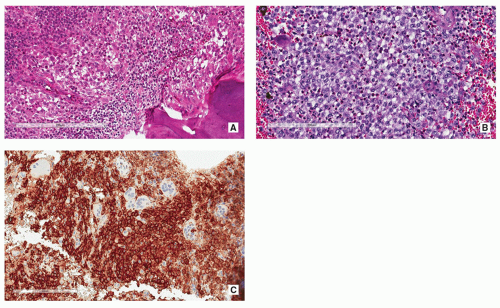

Langerhans cells are frequently admixed with inflammatory cells including large numbers of eosinophils, lymphocytes, neutrophils, and plasma cells (Figs. 5.10 and 5.11).

Necrosis may be found in a minority of cases, and if it is prominent, is usually the complication of a pathologic fracture.

Mitotic figures may be seen; however, atypical forms are absent.

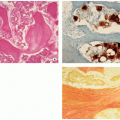

In older or polyostotic lesions, lipid-bearing foam cells can be observed (see Fig. 5.9D).

Special stains may reveal abundant droplets of sudanophilic fat peripherally or in the middle of the giant cell cytoplasm, so-called Touton cells.

Langerhans cells are positive for CD1a, S-100 protein (see Figs. 5.10C and 5.11C,D), and Langerin/CD207, but negative for CD68 and CD45.

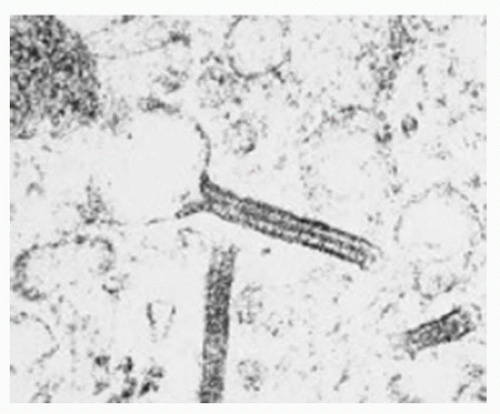

Intracytoplasmic “tennis racquet”-shaped inclusion bodies (organelles), known as Birbeck granules, are diagnostic for this disorder (Fig. 5.12).

Treatment and prognosis of LCH depends on the site and size of the lesion, the age of the patient, and the presence or absence of multifocal disease.

Monostotic disease is usually managed by curettage; however, tumors located in areas difficult to excise may be treated with low dose of radiation.

Single- or multi-agent therapy may be administered in the setting of disseminated disease.

Complete resolution may follow treatment or occasionally may occur spontaneously.

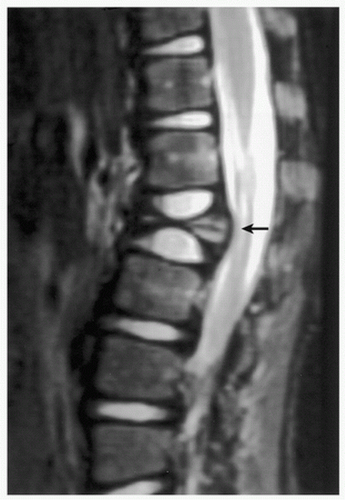

FIGURE 5.8 Magnetic resonance imaging of Langerhans cell histiocytosis. A sagittal T2-weighted MR image shows compression of the ventral aspect of the thecal sac by fractured vertebral body (arrow). |

Also known as sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy, this rare, proliferative, histiocytic disease of unknown etiology is characterized by the enlargement of lymph node sinuses caused by an aggregation of histiocytic cells that exhibit marked lymphophagocytosis (numerous phagocytized lymphocytes are present in the cytoplasm).

Majority of patients are teenagers and young adults.

Mean age of presentation is 20 years.

No gender preference.

Solitary lesion in bones was described in young children.

Tibia, femur, clavicle, skull, maxilla, calcaneus, metacarpals, and sacrum.

Fever and massive cervical lymphadenopathy are the most common symptoms at presentation.

Other symptoms include weight loss, malaise, and night sweats.

Quite often the disease fully manifests after a short period of a nonspecific fever and pharyngitis.

Primary or secondary involvement of extranodal sites, including the skeleton, is common.

Skeletal involvement manifests by the presence of solitary or multifocal defects with poorly or well-demarcated (sclerotic) borders.

The intramedullary lesions are associated with cortical erosion, complete cortical disruption, periosteal reaction, or a combination of these features.

Radiographic manifestations and clinical symptoms may suggest an inflammatory disorder, such as osteomyelitis.

Scintigraphy using gallium scanning shows increased uptake of the radiopharmaceutical agent.

FDG-PET scanning shows increased metabolism.

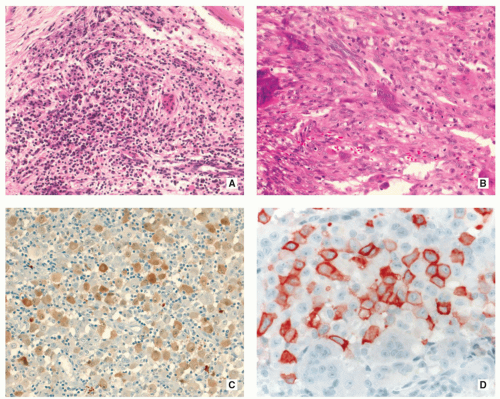

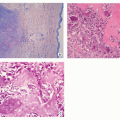

In typical cases, the sinuses of lymph nodes are filled with large, pale histiocytic cells of varying size.

These cells have prominent eosinophilic cytoplasm, indistinct borders, and round or oval nuclei with a very fine chromatin pattern and a single small nucleolus.

Nuclear grooves are not present, and some of these cells may have several nucleoli.

Occasionally, cells with multilobulated nuclei may be present.

Mitotic figures are rare; atypical mitoses are not present.

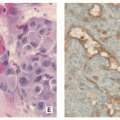

The most striking and diagnostically important feature of histiocytic cells is prominent emperipolesis or lymphophagocytosis (i.e., the presence of well-preserved lymphocytes within the histiocytic cell cytoplasm) (Fig. 5.13A).

In addition to lymphocytes, a smaller number of phagocytized plasma cells, neutrophils, and red cells are also present.

Extranodal disease, including skeletal system, has all these features except that histiocytic cells, instead of growing in sinuses, form irregular geographic areas separated by other inflammatory cells.

Histiocytic cells are positive for S-100 protein (Fig. 5.13B) but negative for CD1a.

This disease is considered a histologically benign, proliferative, histiocytic disorder with a variable, but occasionally fatal, outcome.

The majority of patients have indolent regressive or clinically stable disease after several years.

Fatal outcome of the disease is associated with the severe involvement of extranodal sites (lungs and kidney).

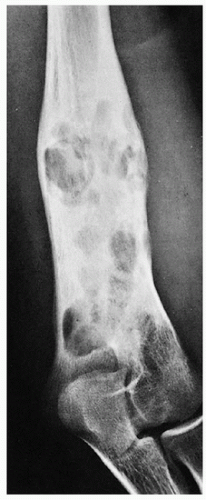

Rare disseminated histiocytic disorder of unknown cause characterized by infiltration of musculoskeletal system and various organs including the heart, lungs, and skin by lipidladen histiocytes leading to fibrosis and osteosclerosis.

Slight male predominance.

Age range between 7 and 84 years with mean age of 53.

Mostly affects the major long bones with sparing of the articular ends.

Rarely the flat bones can be involved.

Extraskeletal involvement may occur, for example, kidney, heart, lungs, and skin.

Mild bone pain sometimes associated with soft-tissue swelling.

Extraskeletal manifestations may include general weakness, fever, weight loss, abdominal pain, shortness of breath, neurologic dysfunction, exophthalmos, diabetes insipidus, kidney failure, hepatosplenomegaly, and eyelid xanthomas.