FOR CONGENITAL

HEART DISEASE

3

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION

Congenital heart disease (CHD) is the most common congenital abnormality in the human fetus, and it accounts for more than half of the deaths from congenital abnormalities in childhood (1). Several risk factors for CHD, including maternal and fetal factors, have been reported (Chapter 1). Fetal echocardiography has been shown to identify the majority of structural cardiac abnormalities (2), and has traditionally been reserved for pregnancies at increased risk for CHD. Most neonates born with CHD, however, have no preidentified risk factors (2). In fact, of all pregnancies referred for fetal echocardiography, the highest incidence of CHD (50%) occurs in pregnancies with a suspected CHD on a routine ultrasound examination (3). In order to improve the prenatal detection of CHD, a screening test, which can be offered to all pregnancies, is required.

Despite the accuracy of fetal echocardiography, second-trimester detection of CHD occurs infrequently in the population at present (4). In a randomized design study in the United States, the detection rate of CHD in the second trimester of pregnancy was 4 of 22 (18%) and 0 of 17 (0%) in tertiary and nontertiary centers, respectively (5,6). Similar disappointingly low rates (15% at 18 weeks) have been reported in a large randomized controlled trial in Europe (7). A prenatal CHD detection rate of 21% was also reported in a study involving more than 77,000 infants over a period of 5 years (1999 to 2003) (8), and a detection rate of 35% was noted in a large population-based study that included first-trimester risk assessment by nuchal translucency (9). Other studies have shown enhanced prenatal detection of CHD, albeit with significant room for improvement. A nonselected population-based study has recently shown a 57% prenatal detection rate for major CHD, with a 44% detection rate of isolated cardiac lesions (10). Prenatal diagnosis of CHD in cases referred to a pediatric cardiology group has increased from 8% to 50% in the period from 1992 to 2002 in one center in the United States (11). Despite these encouraging studies, prenatal detection rates for isolated CHD have remained significantly below 50% and have lagged behind detection rates of other congenital malformations. Efforts should be directed toward enhancing the detection of CHD in utero in view of evidence suggesting improved neonatal morbidity and mortality in prenatally diagnosed CHD (12,13). Targeted education and training of sonographers and sonologists have been shown to improve detection of CHD in the population (14,15). Recent research directed toward lessening the operator dependency of the ultrasound examination by using automated three-dimensional sonography shows significant promise (16–18). Until the ultrasound technology becomes more standardized and automated, a high level of suspicion for the presence of CHD and attention to anatomic details should be part of every ultrasound examination.

THE FOUR-CHAMBER VIEW

THE FOUR-CHAMBER VIEW

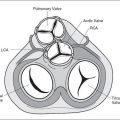

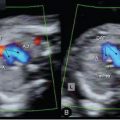

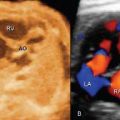

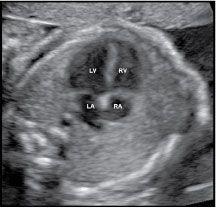

With the widespread use of routine ultrasound examination in pregnancy, the four-chamber view of the fetal heart has been proposed as a screening test for CHD (19) (Fig. 3-1). The four-chamber view of the heart has several features that make it a good screening test for CHD. It is part of the basic obstetric ultrasound examination (20,21). It does not require specialized ultrasound skills as it is easily imaged in a transverse view of the fetal chest. It is obtainable in all fetal positions and in more than 95% of ultrasound examinations performed after 19 weeks of gestation (22).

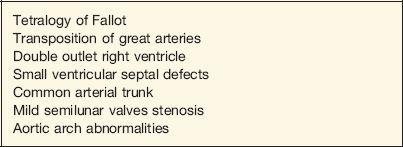

Several specific cardiac abnormalities are associated with a normal four-chamber view of the fetal heart. This represents a major limitation for the routine use of the four-chamber view in screening for CHD in pregnancy. Table 3-1 lists cardiac abnormalities that are commonly associated with a normal four-chamber view of the fetal heart, and Table 3-2 lists cardiac

Figure 3-1. Normal four-chamber view of the fetal heart obtained in a transverse view of the chest. LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle.

| TABLE 3-1 | Cardiac Abnormalities Commonly Associated with a Normal Four-chamber View of the Heart |

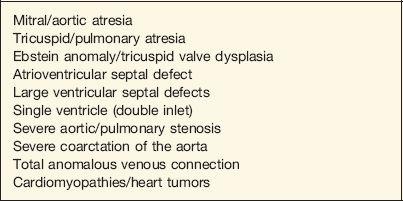

abnormalities that are commonly associated with an abnormal four-chamber view of the fetal heart.

A four-chamber view (Fig. 3-1) of the fetal heart should be considered normal only when the following conditions are met:

1. The fetal situs is normal.

2. The size of the heart in relation to the chest is normal.

| TABLE 3-2 | Cardiac Abnormalities Commonly Associated with an Abnormal Four-chamber View of the Heart |

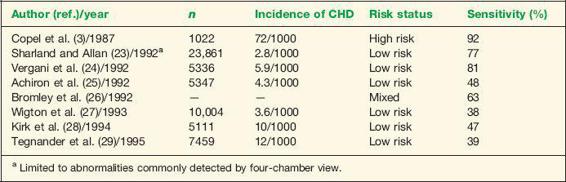

| TABLE 3-3 | The Four-chamber View of the Heart and Prenatal Screening for Congenital Heart Disease |

3. The two atria are equal in size and the flap of the foramen ovale is seen within the left atrium.

4. The two ventricles are equal in size and contractility, with the moderator band imaged in the apex of the right ventricle.

5. The atrial and ventricular septae are normal appearing.

6. The atrioventricular valves are normal appearing where the tricuspid valve appears to insert more apically on the ventricular septum.

Detailed discussion of ultrasonographic fetal cardiac anatomy is presented in the following chapters.

The validity of the four-chamber view in screening for CHD in the fetus has been evaluated by several investigators (3,23–29). Studies differ in the prevalence of CHD in the study population, the risk status of the targeted pregnancies, the operator’s expertise, the ascertainment bias, and the study design. These differences undoubtedly contribute to wide variation in the sensitivity of the four-chamber view in screening for CHD in pregnancy. Clinical factors that may affect the ability to obtain a satisfactory four-chamber view include maternal obesity, fetal position within the uterus, gestational age, and prior maternal abdominal surgery (30). In general, studies evaluating the four-chamber view in low-risk populations are associated with a low sensitivity for the detection of CHD (25,27–29). Even within the same ultrasound laboratory, a significant difference in the sensitivity of the four-chamber view is noted between that in low-risk pregnancies and that in high-risk pregnancies (31). Data from studies evaluating the validity of the four-chamber view in screening for CHD are summarized in Table 3-3.

EXTENDED BASIC EXAMINATION

EXTENDED BASIC EXAMINATION

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree