Second and Third Trimester Pregnancy

John Gullett

David C. Pigott

INTRODUCTION

Clinician-performed evaluation of pregnancy with ultrasound is standard practice in obstetrics and the primary modality for radiologic assessment of pregnancy. Emergency physicians have established first trimester sonography as a standard part of emergency medicine training and practice, primarily to address the risk of undiagnosed ectopic pregnancy. Emergency department (ED) ultrasound evaluation of second and third trimester pregnancies by emergency physicians is less well defined and little studied. This is most likely due to the relative infrequency of ED presentations at this gestational age as complications are fewer and prenatal care is more commonly established and available to the patient. Nevertheless, emergency physicians are still confronted with second or third trimester patients with a variety of complaints, complications, and emergencies. It is essential that the emergency physician understand the role bedside ultrasound can play at these stages of pregnancy, as well as its indications, techniques, findings, and limitations.

Although there is a vast body of literature on the use of ultrasound throughout pregnancy, the lack of a well-defined scope for point-of-care second and third trimester ED ultrasound necessitates caution on the part of the emergency physician. A 1998 study by Sanders found that 75% of all ultrasound-related lawsuits related to obstetrics (1). Many of these relate to failure to diagnose abnormalities on routine, elective ultrasounds; some relate to the failure to obtain an ultrasound when indicated. Emergency physicians, who are knowledgeable in ultrasound anatomy, and trained and skilled in pregnancy applications, may be in a position to obtain valuable information in emergency situations but should exercise professional judgment in the use of late trimester ultrasound.

ED ultrasound is directed at obtaining specific, focused information that is relevant to the patient’s presentation to guide immediate clinical decision making. In pregnancy, this may include basic skills such as gestational dating, fetal heart rate measurement, determination of fetal lie and placental location, and recognition of specific pathologic conditions. ED ultrasound can facilitate the evaluation of pregnant patients who present with trauma, abdominal pain, vaginal bleeding, labor, as well as nonobstetric emergencies, such as cholecystitis and appendicitis. Sonography of the second and third trimester patient may be needed infrequently in high-volume EDs in countries with well-developed health systems. However, these skills may be

particularly useful when bedside ultrasound is the most immediate resource at hand, such as rural practice settings, austere environments, or in developing countries. One report on the utilization of acute ultrasound in Liberia found that 53% were for obstetric-related complaints; 17% of the patients were second or third trimester, and management was altered in 77% (2).

particularly useful when bedside ultrasound is the most immediate resource at hand, such as rural practice settings, austere environments, or in developing countries. One report on the utilization of acute ultrasound in Liberia found that 53% were for obstetric-related complaints; 17% of the patients were second or third trimester, and management was altered in 77% (2).

CLINICAL APPLICATIONS

Emergency ultrasound is designed to focus on limited goal-directed exams to guide therapy, consults, hospital transfers, and risk stratification. The goal of the emergency physician is not to perform comprehensive fetal biometry or anatomical surveys, but rather to quickly gather relevant data necessary for immediate care.

Some of the ultrasound evaluation done in the second and third trimester performed by technicians and radiologists is beyond the scope of emergency physicians. However, point-of-care ultrasound can be a critical diagnostic tool for patients with third trimester bleeding, trauma, abdominal pain, fluid leakage, and labor. Emergency pathology such as placenta previa, uterine rupture, premature rupture of membranes, fetal viability, pregnancy dating, and fetal cardiac activity may all be assessed by emergency physicians (Table 16.1).

Other indications for emergency ultrasound, discussed in other sections of this book, apply to the pregnant patient as well. It is necessary to maintain a wide differential when evaluating a pregnant patient with abdominal pain. For instance, the discomfort of cholecystitis or appendicitis may be mistaken for labor pains. It is important to remember that, if used properly, point-of-care ultrasound can narrow the differential diagnosis or redirect the clinician toward a difficult diagnosis.

IMAGE ACQUISITION

Transabdominal Imaging

Transabdominal sonography is virtually always sufficient in the second and third trimester for ED exams. At this stage the gravid uterus is large relative to other organs, and a low-frequency curvilinear or phased array transducer provides adequate depth of penetration. A curvilinear transducer provides the greatest field of view and is preferable.

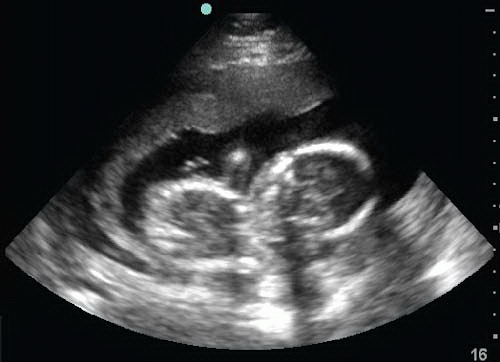

Transabdominal visualization of the normal second and third trimester pregnancy is typically an intuitive and straightforward process. The sonographer is aided by ample amniotic fluid, which provides an acoustic window surrounding the fetus. Technique is largely guided by the needs of the clinician as well as by the position of the fetus, placenta, and other structures. The sonographer may have to spend some time placing the transducer in multiple positions on the abdomen, orienting to a given pregnancy’s individual anatomy in order to appreciate the positions of important structures (Figs. 16.1 and 16.2).

TABLE 16.1 Indications for Point-of-Care Ultrasound in Second/Third Trimester Pregnancy | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

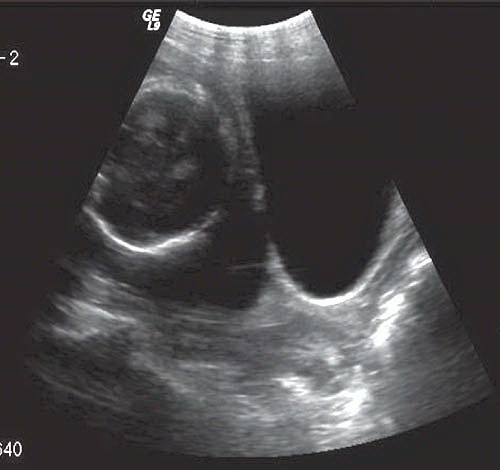

The normal second and third trimester uterus appears as a homogeneous muscular wall of medium to low echogenicity. Throughout pregnancy it decreases in thickness as it stretches to accommodate the pregnancy. The lower uterine segment can sometimes be seen in the pelvis (Fig. 16.3; eFig. 16.1). Transabdominal ultrasound of this area may be impaired by maternal habitus. However, with a moderately full bladder, the lower uterus and cervix can often be visualized.

Transvaginal Imaging

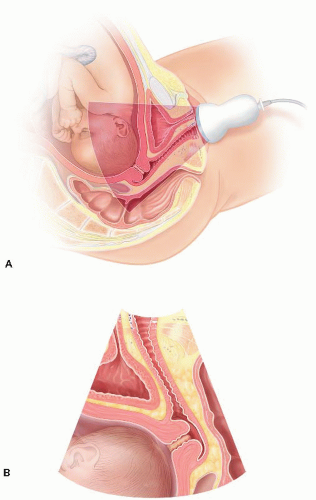

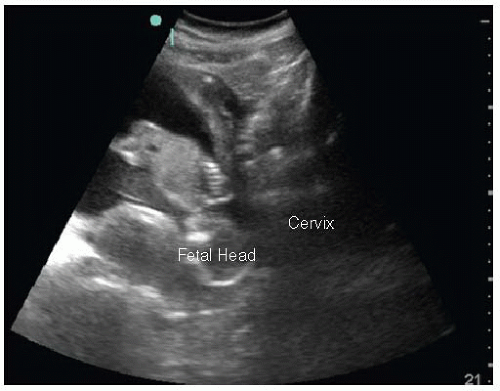

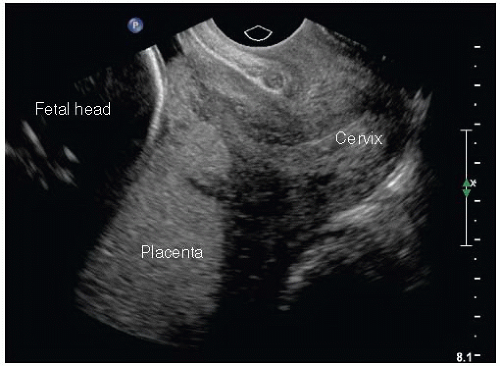

While transabdominal ultrasound is the technique of choice for most late trimester evaluations, transvaginal sonography affords superior views of the lower uterine segment

and cervix, as well as their position relative to the placenta (Fig. 16.4). The transvaginal approach is not recommended in the setting of premature rupture of membranes, and its use should be considered with caution in the setting of potential placenta previa, though it is not, in fact, contraindicated. In the ED a transabdominal exam should always be performed first, with the transvaginal ultrasound generally a second-line choice. Nonetheless, the combination of transabdominal and transvaginal views may provide synergistic information for an otherwise unclear diagnosis.

and cervix, as well as their position relative to the placenta (Fig. 16.4). The transvaginal approach is not recommended in the setting of premature rupture of membranes, and its use should be considered with caution in the setting of potential placenta previa, though it is not, in fact, contraindicated. In the ED a transabdominal exam should always be performed first, with the transvaginal ultrasound generally a second-line choice. Nonetheless, the combination of transabdominal and transvaginal views may provide synergistic information for an otherwise unclear diagnosis.

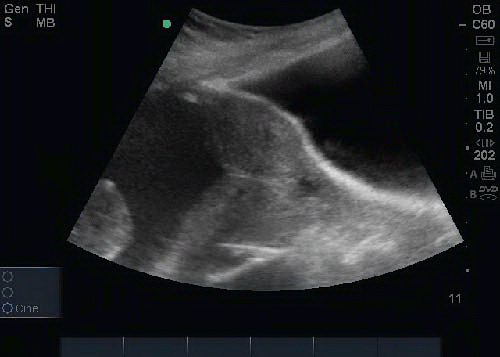

FIGURE 16.1. Transabdominal Ultrasound of the Uterus Shown with a Curvilinear Transducer. The placenta is seen posterior to the fetus. |

FIGURE 16.4. Transvaginal Ultrasound of a Normal Second Trimester Pregnancy. The fetal head is anterior/cranial, and the placenta is seen in the posterior uterus. |

The technique does not differ from that described in Chapter 14, although it is advisable in later pregnancy to insert the transducer with careful, gentle, pressure so as not to disrupt a friable vascular structure (if concerned for placenta previa) or distort the cervix (if measuring cervical length). For these reasons, the tip of the transducer should reach no further than 2 to 3 cm from the cervix.

Transperineal (Translabial) Imaging

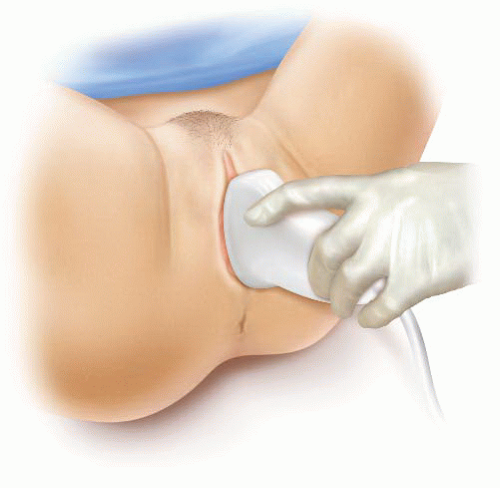

Transperineal (or translabial) ultrasound, unfamiliar to most emergency physicians, may be useful in situations when the digital exam is undesirable, unclear, or contraindicated, and the transvaginal approach is unfavorable, or when an endocavitary probe is simply unavailable. The technique is safe in all stages of pregnancy and labor, except for the potential danger from an inexperienced clinician who may misinterpret findings. The transperineal approach is used to visualize the lower uterine segment and cervix.

With the patient in the supine lithotomy position, a low-frequency curvilinear or phased array transducer is usually covered with a plastic barrier or glove and placed on the perineum or between the labia major and labia minora in a sagittal plane (Figs. 16.5 and 16.6) (3). This technique does not require a full bladder, but some urine makes the bladder a distinctive and useful landmark for anatomic orientation. The transducer surface should be inferior to the urethra and anterior to the vaginal orifice. The image and anatomic orientation is similar to that obtained by the transvaginal approach. The cervix is identified posterior to the bladder by its thick muscular walls and the thin line of the endocervical canal, which may appear hyperechoic or hypoechoic, but is typically a distinctive straight line (Fig. 16.7). The far field should include the internal cervical os, the lower uterine segment, and some amniotic fluid. The relationship of the placenta, if present, can be noted at the internal cervical os. During labor the fetal head can be seen as well.

There is a statistically significant correlation between the digital cervical exam and the transperineal sonographic assessment of cervical dilation, length, and station (4). In one study, in 97% of cases (n = 184) adequate diagnostic information regarding the lower uterine segment was obtained with the transperineal approach (5). This technique has not

been validated as a point-of-care emergency ultrasound application to augment a digital cervical exam by emergency physicians, or replace it in the setting of possible previa, but in certain circumstances, with good understanding of the technique, it may be a reasonable approach to consider.

been validated as a point-of-care emergency ultrasound application to augment a digital cervical exam by emergency physicians, or replace it in the setting of possible previa, but in certain circumstances, with good understanding of the technique, it may be a reasonable approach to consider.

NORMAL ULTRASOUND ANATOMY

Gestational Dating

There are numerous approaches to determining gestational age with ultrasound. The emergency physician requires a gestational dating technique that is brief, yet reliable for clinical decision making. When faced with a patient of indeterminate gestational age, an accurate estimate of gestational age is necessary to anticipate the types of complications they may experience, as well as to determine if the presenting complaint is related to the pregnancy or a coexisting medical condition, and to decide what management options are best for the mother and fetus. Determining age of viability by date is a major reason that emergency physicians need to have some rapid method of determining gestational age. This factor may affect decision making when the mother is in medical or traumatic distress.

In the second and third trimester, emergency physicians have several options for fetal dating: biparietal diameter (BPD), head circumference (HC), femur length (FL), and abdominal circumference (AC). The accuracy of these methods varies at different stages of pregnancy, with all three decreasing in accuracy through the third trimester, but each has been shown to have a high intra- and interobserver reliability (6,7). The ease of measurement depends on fetal lie and anatomy, as well as uterine/placental anatomy, body habitus, and the presence of fetal anomalies. In general, the emergency physician should be familiar with all three techniques, and may use any of these with reasonable reliability for the purpose of an emergency ultrasound assessment.

The three techniques outlined here are comparable, but use of multiple parameters provides a greater degree of accuracy. For the emergency physician, an adequate and rapid assessment may be made with whichever technique affords the greatest confidence on the part of the sonographer. However, it should be noted that multiple techniques should always be used for each pregnancy to ensure agreement within approximately a week to reveal any technical error on one method or an outlier result due to congenital anomalies or growth retardation.

Chervenak et al. studied 152 singleton gestations and found that HC was the best predictor of gestational age (8). Other studies have supported this finding as well, though it is still not considered an established fact (9, 10, 11). The term “fetal biometry” refers to the use of multiple techniques in combination, which produces the greatest accuracy.

Biparietal diameter

BPD is an easily obtained metric with distinctive landmarks that are relatively easy to acquire. Its accuracy when used alone may be inferior, since it depends on fetal head shape, which varies more in the third trimester (8). Nonetheless, for general use in the ED, BPD is an appropriate choice for either second or third trimester dating.

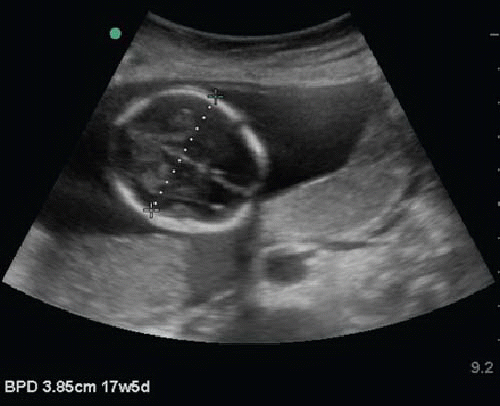

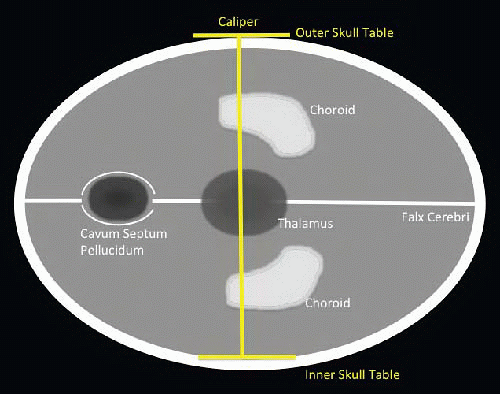

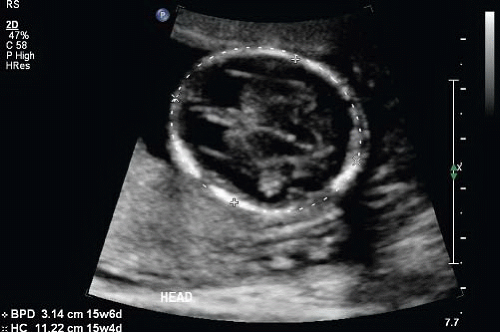

BPD is measured with an axial view of the fetal head. The important landmarks are (1) the midline falx cerebri, (2) the hypoechoic central thalami, (3) the septum pellucida anterior to the thalamus, and (4) the hyperechoic bulb-like choroid plexus, which may be seen bilaterally and slightly posterior. Measuring calipers are placed at the outer skull table located

closest to the transducer and then on the inner skull table that is furthest from the transducer. Most ultrasound devices have software applications that will calculate the gestational age based on this measurement (Figs. 16.8 and 16.9; eFig. 16.2).

closest to the transducer and then on the inner skull table that is furthest from the transducer. Most ultrasound devices have software applications that will calculate the gestational age based on this measurement (Figs. 16.8 and 16.9; eFig. 16.2).

Head circumference

HC provides a simple and accurate estimate of gestational age in the second and third trimester. Even in the setting of many growth disorders that may skew other techniques, HC has acceptable accuracy (6,8,12,13). Ott reviewed 1278 cases in 710 normal pregnancies, and calculated the mean error of HC, BPD, and last menstrual period (LMP). He found the error of HC superior to both LMP and BPD (13). The proper plane in which to measure HC is essentially the same as described for BPD: an axial plane containing the thalamus, cavum septum pellucidum, and the falx cerebri. The goal is to obtain the plane of greatest anterior-posterior cranial length. Caliper cursors should be placed on the outer calvarial mantles anterior and posterior (Fig. 16.10; eFig. 16.3) (12). Avoid including the skin overlying the skull, as this will falsely increase the calculated gestational age.

Femur length

Though generally less accurate than BPD, FL can be measured as early as 10 weeks and is a good choice for ED gestation age determination due to its simple and consistent anatomy (6,14,15). Jeanty et al. found FL to be accurate to within ±2.8 weeks at any point in pregnancy (14). The femur is located by following the knee or hip/pelvis. The spine is an easy landmark to follow down to the pelvis to locate the femur from the hip. Care must be taken to align the transducer parallel exactly along the long axis of the femur (Fig. 16.11; eFig. 16.4). Only the shaft of the femur is measured from the greater trochanter to the distal femoral diaphysis. The epiphyses are excluded, and only osseus bone is measured, not cartilage. This technique is only accurate in an orthopedically normal fetus; growth retardation and skeletal dysplasias will alter the calculated date. Pitfalls include nonvisualization of the entire femoral diaphysis, failure to align precisely along the long axis of the femur, measuring the epiphysis, and misidentification of other bones as the femur.

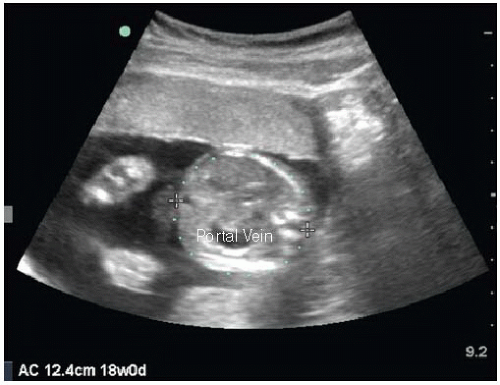

Abdominal circumference

Abdominal circumference is obtained in the axial plane through a section of the fetal abdomen at the level of the liver. Other landmarks that should be visible are the fetal

stomach, gallbladder, and ductus venosus. The plane should be perpendicular to the spine, and ribs should be seen symmetrically containing the area. Similar to HC, a measuring circle is arranged along the perimeter of this axial section (Fig. 16.12; eFig. 16.5). This measurement is the least accurate in terms of gestational dating, but most predictive of fetal growth (10). Fetal growth patterns are less concerning to the emergency physician, so this method may be useful mainly as a secondary or confirmatory application.

stomach, gallbladder, and ductus venosus. The plane should be perpendicular to the spine, and ribs should be seen symmetrically containing the area. Similar to HC, a measuring circle is arranged along the perimeter of this axial section (Fig. 16.12; eFig. 16.5). This measurement is the least accurate in terms of gestational dating, but most predictive of fetal growth (10). Fetal growth patterns are less concerning to the emergency physician, so this method may be useful mainly as a secondary or confirmatory application.

FIGURE 16.11. Technique for Measuring Femur Length. This a transabdominal approach using a curvilinear transducer. |

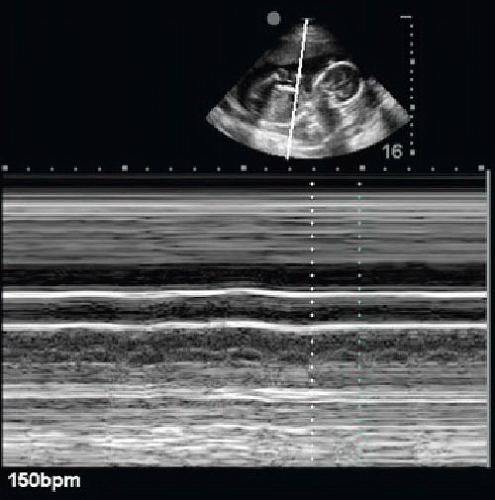

Fetal Cardiac Activity

As in first trimester ultrasound, fetal heart rate (FHR) is easily measured in the second and third trimester using M-mode. The fetal heart is easily identified in the chest by its rapid contractions. To measure the heart rate, first identify the fetal heart at a point where cardiac motion is greatest. Next, activate M-mode and identify the characteristic rapid motion tracing that stands out from other movements as a regular high-frequency repeating waveform that represents cardiac contractions. Most ultrasound units contain a FHR calculation function to activate and place two caliper markers at similar points on the tracing of two adjacent heartbeats. The machine will calculate a heart rate in real time as the second caliper end is moved in place (Fig. 16.13;  VIDEO 16.1). It is difficult, but possible, to count a pulse visually. Some basic machines may not have the M-mode function, in which case a video clip of the beating heart may be recorded simply as a record of fetal cardiac activity. The use of color or spectral Doppler is not recommended in pregnancy as these modalities transmit slightly greater energy than gray-scale sonography, which, theoretically, may damage vulnerable fetal cells.

VIDEO 16.1). It is difficult, but possible, to count a pulse visually. Some basic machines may not have the M-mode function, in which case a video clip of the beating heart may be recorded simply as a record of fetal cardiac activity. The use of color or spectral Doppler is not recommended in pregnancy as these modalities transmit slightly greater energy than gray-scale sonography, which, theoretically, may damage vulnerable fetal cells.

VIDEO 16.1). It is difficult, but possible, to count a pulse visually. Some basic machines may not have the M-mode function, in which case a video clip of the beating heart may be recorded simply as a record of fetal cardiac activity. The use of color or spectral Doppler is not recommended in pregnancy as these modalities transmit slightly greater energy than gray-scale sonography, which, theoretically, may damage vulnerable fetal cells.

VIDEO 16.1). It is difficult, but possible, to count a pulse visually. Some basic machines may not have the M-mode function, in which case a video clip of the beating heart may be recorded simply as a record of fetal cardiac activity. The use of color or spectral Doppler is not recommended in pregnancy as these modalities transmit slightly greater energy than gray-scale sonography, which, theoretically, may damage vulnerable fetal cells.While easy to perform and potentially clinically useful, analyzing FHR other than to say it is within normal limits is beyond the scope of emergency ultrasound. Tocometry is preferential for detecting changes in heart rate that may indicate fetal distress. Nonetheless, bedside ultrasound is capable of measuring FHR, and is easily repeatable to recheck the rate as circumstances dictate or if tocography is unavailable.

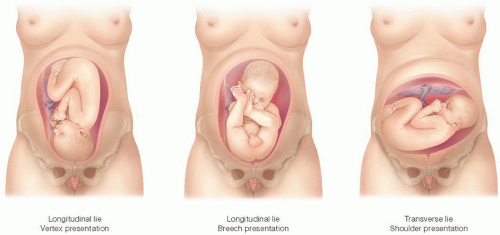

Fetal Lie

Determining the fetal position with ultrasound is indicated when a patient is in active labor and obstetric consultation is not immediately available. The goal-directed question under these circumstances is whether the fetus is in vertex or breech position. If the presence of a breech position is known early, the emergency physician is able to make an informed decision on how best to proceed, for example, prepare for a breech delivery in the ED if imminent, or initiate tocolysis while arranging obstetrician involvement.

The technique is simple and intuitive. Transabdominal sonography is used to locate the position of the fetal head (Fig. 16.14). The preferable position is vertex with the head down into the pelvis and occiput anterior (Fig. 16.15). This allows the smallest part of the fetal head to exit first. If the head is difficult to locate, this may be because it is engaged in the maternal pelvis. A simplified approach is to confirm that the fetal head is not anywhere in the fundus. If the head is seen in the fundus, then the fetus is in breech position (Fig. 16.16). If the lower extremities are adjacent to the fetal head in the fundus, a frank breech is present. This is the most common type of breech presentation. In a complete breech presentation, the feet are down in the pelvis instead of upward near the fetal head in the fundus. Transverse lie will be evident when the fetal head is seen in the midlateral aspect of the uterus. In this position a shoulder presentation may be anticipated. The fetal spine is a good landmark as it produces a strikingly characteristic appearance on ultrasound. Once located, the spine may be followed to the fetal head or pelvis. The orientation of the spine to the maternal body indicates vertical or transverse lie. It is important to remember that abnormal positions will usually self-correct as pregnancy progresses; however, in the setting of active labor or rupture of membranes, the emergency physician may have to anticipate a complicated delivery or indication for cesarean section.

Placental Location

Placental location should be determined on any patient presenting to the ED in active labor if an obstetric consultation is not immediately available. The most important question at this point is to verify the presence or absence of a placenta previa.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree